The International Journal of Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Study Guide for Teachers and Students

Melody Mennite in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE AND POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION Learning Outcomes & TEKS 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of Cinderella 7 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Choreographer 11 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Composer 12 The Artists who Created Cinderella Designer 13 Behind the Scenes: “The Step Family” 14 TEKS ADDRESSED Cinderella: Around the World 15 Compare & Contrast 18 Houston Ballet: Where in the World? 19 Look Ma, No Words! Storytelling in Dance 20 Storytelling Without Words Activity 21 Why Do They Wear That?: Dancers’ Clothing 22 Ballet Basics: Positions of the Feet 23 Ballet Basics: Arm Positions 24 Houston Ballet: 1955 to Today 25 Appendix A: Mood Cards 26 Appendix B: Create Your Own Story 27 Appendix C: Set Design 29 Appendix D: Costume Design 30 Appendix E: Glossary 31 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Students can describe how ballets tell stories without words; • Compare & contrast the differences between various Cinderella stories; • Describe at least one dance from Cinderella in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. §114.22. LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH LEVELS I AND II (4) Comparisons. The student develops insight into the nature of language and culture by comparing the student’s own language §110.25. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING, READING (9) The student reads to increase knowledge of own culture, the culture of others, and the common elements of cultures and culture to another. -

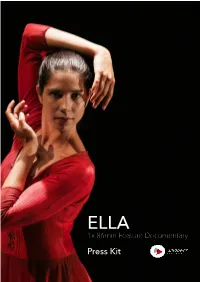

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première Catalogue 2018 Lists UNITEL’S New Productions of 2017 CATALOGUE 2018 Plus New Additions to the Catalogue

CATALOGUE 2018 This Avant Première catalogue 2018 lists UNITEL’s new productions of 2017 CATALOGUE 2018 plus new additions to the catalogue. For a complete list of more than 2.000 UNITEL productions and the Avant Première catalogues of 2015–2017 please visit www.unitel.de FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany WORLD SALES CEO: Jan Mojto C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Editorial team: Franziska Pascher, Dr. Martina Kliem, Arthur Intelmann Layout: Manuel Messner/luebbeke.com Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager All information is not contractual and subject to change without prior notice. [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] All trademarks used herein are the property of their respective owners. [email protected] Date of Print: February 2018 © UNITEL 2018 All rights reserved Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director Front cover: Alicia Amatriain & Friedemann Vogel in John Cranko’s “Onegin” / Photo: Stuttgart Ballet [email protected] [email protected] ON THE OCCASION OF HIS 100TH BIRTHDAY UNITEL CELEBRATES AVAILABLE FOR THE FIRST TIME FOR GLOBAL DISTRIBUTION LEONARD BERNSTEIN 1918 – 1990 Leonard Bernstein, a long-time exclusive artist of Unitel, was America’s ambassador to the world of music. -

Palacio De Bellas Artes

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE BELLAS ARTES DANZA SECRETARÍA DE CULTURA María Cristina García Cepeda Secretaria Saúl Juárez Vega Subsecretario de Desarrollo Cultural Jorge Gutiérrez Vázquez Subsecretario de Diversidad Cultural y Fomento a la Lectura Francisco Cornejo Rodríguez Oficial Mayor INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE BELLAS ARTES Lidia Camacho Camacho Directora general Roberto Vázquez Díaz Subdirector general Silvia Carreño y Figueras Gerente del Palacio de Bellas Artes Cuauhtémoc Nájera Ruiz Coordinador Nacional de Danza Roberto Perea Cortés Director de Difusión y Relaciones Públicas Foto: Carlos Quezada PALACIO DE BELLAS ARTES GALA ELISA Y AMIGOS 2017 PROGRAMA Diamantes Pas de deux del ballet Joyas Coreografía: George Balanchine Música: Piotr Ilich Chaikovski Ballet Bolshói Intérpretes: Evgenia Obraztsova y Semyon Chudin Onegin Pas des deux. 1.° acto Coreografía: John Cranko Música: Piotr Ilich Chaikovski Staatsballett Berlin Intérpretes: Elisa Carrillo y Mikhail Kaniskin El cascanueces Pas de deux Coreógrafo: Lev Ivanov / Marius Petipa Música: Piotr Ilich Chaikovski New York City Ballet Intérpretes: Ashley Bouder y Joseph Gatti Simple Things Pas de deux Coreografía: Radu Poklitaru Música: Chavela Vargas Staatsballett Ucrania Intérpretes: Ekaterina Kukhar y Alexander Stoianov La danza del venado Coreografía: Amalia Hernández Música: Yaqui (D.P.) Ballet Folklórico de México de Amalia Hernández Intérpretes: Fausto - venado y Tonatiuh, Yair - pascolas El corsario Pas de deux Coreografía: Marius Petipa Música: Adolph Adam Ballet de Múnich / Ballet Mariinski -

18Th Century Dance

18TH CENTURY DANCE THE 1700’S BEGAN THE ERA WHEN PROFESSIONAL DANCERS DEDICATED THEIR LIFE TO THEIR ART. THEY COMPETED WITH EACH OTHER FOR THE PUBLIC’S APPROVAL. COMING FROM THE LOWER AND MIDDLE CLASSES THEY WORKED HARD TO ESTABLISH POSITIONS FOR THEMSELVES IN SOCIETY. THINGS HAPPENING IN THE WORLD IN 1700’S A. FRENCH AND AMERICAN REVOLUTIONS ABOUT TO HAPPEN B. INDUSTRIALIZATION ON THE WAY C. LITERACY WAS INCREASING DANCERS STROVE FOR POPULARITY. JOURNALISTS PROMOTED RIVALRIES. CAMARGO VS. SALLE MARIE ANNE DE CUPIS DE CAMARGO 1710 TO 1770 SPANISH AND ITALIAN BALLERINA BORN IN BRUSSELS. SHE HAD EXCEPTIONAL SPEED AND WAS A BRILLIANT TECHNICIAN. SHE WAS THE FIRST TO EXECUTE ENTRECHAT QUATRE. NOTEWORTHY BECAUSE SHE SHORTENED HER SKIRT TO SEE HER EXCEPTIONAL FOOTWORK. THIS SHOCKED 18TH CENTURY STANDARDS. SHE POSSESSED A FINE MUSICAL SENSE. MARIE CAMARGO MARIE SALLE 1707-1756 SHE WAS BORN INTO SHOW BUSINESS. JOINED THE PARIS OPERA SALLE WAS INTERESTED IN DANCE EXPRESSING FEELINGS AND PORTRAYING SITUATIONS. SHE MOVED TO LONDON TO PUT HER THEORIES INTO PRACTICE. PYGMALION IS HER BEST KNOWN WORK 1734. A, CREATED HER OWN CHOREOGRAPHY B. PERFORMED AS A DRAMATIC DANCER C. DESIGNED DANCE COSTUMES THAT SUITED THE DANCE IDEA AND ALLOWED FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT MARIE SALLE JEAN-GEORGES NOVERRE 1727-1820; MOST FAMOUS PERSON OF 18TH CENTURY DANCE. IN 1760 WROTE LETTERS ON DANCING AND BALLETS, A SERIES OF ESSAYS ATTACKING CHOREOGRAPHY AND COSTUMING OF THE DANCE ESTABLISHMENT ESPECIALLY AT PARIS OPERA. HE EMPHASIZED THAT DANCE WAS AN ART FORM OF COMMUNICATION: OF SPEECH WITHOUT WORDS. HE PROVED HIS THEORIES BY CREATING SUCCESSFUL BALLETS AS BALLET MASTER AT THE COURT OF STUTTGART. -

Wayne Mcgregor | Random Dance

WAYNE MCGREGOR | RANDOM DANCE FEBRUARY 13, 2014 OZ SUPPORTS THE CREATION, DEVELOPMENT AND PRESENTATION OF SIGNIFICANT CONTEMPORARY PERFORMING AND VISUAL ART WORKS BY LEADING ARTISTS WHOSE CONTRIBUTION INFLUENCES THE ADVANCEMENT OF THEIR FIELD. ADVISORY BOARD Amy Atkinson Karen Elson Jill Robinson Anne Brown Karen Hayes Patterson Sims Libby Callaway Gavin Ivester Mike Smith Chase Cole Keith Meacham Ronnie Steine Jen Cole Ellen Meyer Joseph Sulkowski Stephanie Conner Dave Pittman Stacy Widelitz Gavin Duke Paul Polycarpou Betsy Wills Kristy Edmunds Anne Pope Mel Ziegler A MESSAGE FROM OZ Welcome and thank you for joining us for our first presentation as a new destination for contemporary performing and visual arts in Nashville. By being in the audience, you are not only supporting the visiting artists who have brought their work to Nashville for this rare occasion, you are also supporting the growth of contemporary art in this region. We thank you for your continued support. We are exceptionally lucky and very proud to have with us this evening, one of the worlds’ most inspiring choreographic minds, Wayne McGregor. An artist who emphasizes collaboration and a wide range of perspectives in his creative process, McGregor brings his own brilliant intellect and painterly vision to life in each of his works. In FAR, we witness the mind and body as interconnected forces; distorted and sensual within the same frame. As ten stunning dancers hyperextend and crouch, rapidly moving through light and shadow to a mesmerizing score, the relationship between imagination and movement becomes each viewer’s own interpretation. An acronym for Flesh in the Age of Reason, McGregor’s FAR investigates self-understanding and exemplifies the theme from Roy Porter’s novel by the same name, “that we outlive our mortal existence most enduringly in the ideas we leave behind.” Strap in. -

Dernussknacker 9. 12. 18

BAYERISCHES WHAT´SON STAATSBALLETT D D STAGE Please send the listing information in time to [email protected] E I R E DEUTSCHLAND 07,28.12 Romeo und Julia Ch. Luciano Cannito 11,12,14.12 Eine Weihnachtgeschichte Bayerisches Staatsballett Ch. Reiner Feistel Bayerisches Staatsballett 18,23.01 Showcase II – Persona Ch. Peter Svezon www.bayerisches.staatsballett.de 26,27.01 Die Moderne geht baden N K 01,03,13.10;06.11 Anna Karenina Ch. Christian Spuck Landestheater Coburg 06,10.10;19,20.01 Raymonda Ch. Ray Barra www.landestheater-coburg.de U A 10,18,22,23,29.11;05,18.12;09,18.01 Drei Farben U A 27,28.10;01,03.11 Jewels Ch. George Balanchine 22,25,30.11 Alice im Wunderland Ch. Tara Yipp/ Nico Ilias König / Mark McClain Ch. Christopher Wheeldon 14,16,23,26.12;10,12,13.01 First Steps S M Ch. Junge Choreografen S M 09,14,18,26,28.12;02,04.01 Der Nussknacker Ch. John Neumeier Deutsche Oper am Rhein - Ballett am Rhein 10,11,13,26.01 Die Kameliendame www.ballettamrhein.de S E Ch. John Neumeier 05,07,19,27.10;04.11;12,22,26.12;08,12,20.01 b36 Ballett Augsburg Ch. Martin Schläpfer K L www.theater-augsburg.de 23,28.11;01,09,12,15.12;05.01 b37 Ch. Robert K L 27.10;04,17,24.11;04,07,13,15,23.12;09.01 Binet / Natalia Horecna / Remus Sucheana Vier Jahreszeiten Ch. Ricardo Fernando 31.12 Silvester Gala Ch. -

White, Women and the World of Ballet

White, women and the world of ballet Greek fashion, muslin The ballet paintings, drawings and sculptures Muslin was washable and it fell gracefully like the cloth and combustible of the French artist Edgar Degas are known to us all. folds of the costumes on the Greek statues that ballerinas – Michelle His dancers are captured in the studio, in the wings, were unearthed when the ruins of the ancient city Potter takes you backstage, on stage. We see them resting, practising, of Pompeii were excavated. White clothing also through the history of taking class, performing. They are shown from many indicated status. A white garment was hard to keep the innocent white tutu angles: from the orchestra pit, from boxes, as long clean so the well-dressed woman in a pristine white shots, as close-ups. They wear a soft skirt reaching outfit was clearly rich enough to have many dresses just below the knee. It has layers of fabric pushing in her wardrobe. Since ballet costuming at the time it out into a bell shape and often there is a sash followed fashion trends, white also became the at the waist, which is tied in a bow at the back. colour of the new, free-flowing ballet dresses. Most of his dancers also wear a signature band Soon the white, Greek-inspired dress had given of ribbon at the neck. The dress has a low cut bodice way to the long, white Romantic costume as worn with, occasionally, a short, frilled sleeve. More often by the Sylphide and her attendants in La Sylphide. -

Glen Tetley: Contributions to the Development of Modern

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. GLEN TETLEY: CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN DANCE IN EUROPE 1962-1983 by Alyson R. Brokenshire submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences Of American University In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree Of Masters of Arts In Dance Dr. -

Ballet Notes Cover: Greta Hodgkinson and Guillaume Côté (2005)

The Taming of the Shrew March 2007 Ballet Notes Cover: Greta Hodgkinson and Guillaume Côté (2005). This page: John Cranko with Stuttgart Ballet’s Marcia Haydée and Richard Cragun in rehearsal (c.1969). The Taming of the Shrew A ballet in two acts after William Shakespeare Choreography: John Cranko Copyright: Dieter Graefe Produced and Staged by: Reid Anderson Originally Reproduced from the Benesh Notation by: Jane Bourne Music: Domenico Scarlatti, arranged by Kurt-Heinz Stolze, published by Edition Modern AG Set and Costume Design: Susan Benson Lighting Design: Robert Thomson Assistant to Miss Benson: Marjory Fielding This production entered the repertoire of The National Ballet of Canada on February 13, 1992; Walter Carsen, O.C. totally underwrote the original production and generously sponsored the 2006 refurbishment. Presenting Sponsor: 3 Synopsis Baptista, a rich gentleman of Padua, has two Scene 4: A street daughters. The elder, Katherina, an intelligent, All the neighbours gather to attend Katherina’s outspoken woman, is thought to be a shrew by wedding. They find it hysterical that she has the townsfolk. What Katherina really resents is the agreed to marry such a man. Bianca’s suitors preferential attention paid to her silly, vain sister, gleefully join them in a playful, silly dance. Bianca, by everyone. Despite her objections, Scene 5: Baptista’s house Katherina is married to Petruchio. Petruchio mar- Katherina is dragged to her wedding kicking and ries Katherina for her money and sets out to bully screaming by her father. Petruchio arrives late her into submission. But who tames whom, the and behaves outrageously. -

The Paris Opera Ballet and the 2019 Pensions Dispute

Notes from the Field: Work | Strike | Dance Notes from the Field Work | Strike | Dance: The Paris Opera Ballet and the 2019 Pensions Dispute By Martin Young Fig. 1: Paris Opera dancers perform in front of the Palais Garnier against the French government’s plan to overhaul the country’s retirement system, in Paris, on December 24, 2019. (Photo by Ludovic Marin/AFP via Getty Images). The day before Christmas Eve 2019, 27 of the Paris Opera’s ballet dancers, alongside a large contingent of the orchestra, staged a 15 minute excerpt of Swan Lake on the front steps of the Palais Garnier. This performance was part of a wave of strike action by French workers against major proposed pension reforms which had, since the start of December, already seen the closure of schools, rail networks, and attractions like the Eiffel Tower, and drawn hundreds of thousands of people into taking part in protests in the streets. As reports of the labour dispute, which would become the longest running strike in France’s history, spread around the world, footage of the Swan Lake performance gained a disproportionate prominence, circulating virally as one of the 131 Platform, Vol. 14, No. 1 & 2, Theatres of Labour, Autumn 2020 key emblematic images of the action. That ballet dancers might become the avatars of struggling workers, and that workers’ struggle might become the perspective through which to view a ballet performance, is an unexpected situation to say the least. As Lester Tomé writes, ballet is ‘a high-art tradition commonly characterized as elitist and escapist, seemingly antipodal to Marxist principles’ (6).