Annual Report 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Strategy for Norway's Culture and Sports Cooperation

Evaluation Department Evaluation of the Strategy for Norway’s Culture and Sports Cooperation with Countries in the South Report 3/2011 – Evaluation Norad Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation P.O.Box 8034 Dep, NO-0030 Oslo Ruseløkkveien 26, Oslo, Norway Phone: +47 22 24 20 30 Fax: +47 22 24 20 31 Photo: “Skulptur I” by Hans-Jörgen Johanssen Design: Agendum See Design Print: 07 Xpress AS, Oslo ISBN: 978-82-7548-587-6 Evaluation of the Strategy for Norway’s Culture and Sports Cooperation with Countries in the South July 2011 Nordic Consulting Group Core team: Kim Forss (team leader), Nora Ingdal, Stein-Erik Kruse, Ananda S. Millard “Responsibility for the contents and presentation of findings and recommendations rest with the evaluation team. The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily correspond with those of Norad”. Preface The Strategy for Norway’s culture and sports co-operation with countries in the South covers the period 2006-2015, and it is stated in the Strategy that it “will be evaluated and, if necessary, modified in 2010”. The evaluation started in December 2010. It is the second evaluation commis- sioned by the Evaluation Department that specifically covers Norwegian support in the cultural sector. The first one was the Evaluation of Norwegian Support to the Protection of Cultural Heritage, that was carried out in 2008 and 2009. Internationally, there seems to be a lack of independent comprehensive evaluations in culture and sports, in particular the latter. The present evaluation thus deals with an area that has not as yet been covered comprehensively with great frequency, even if there are a larger number of program and project evaluations – more in cul- ture than in sports. -

Organisational Review of Stromme Foundation

Norad Report 14/2008 Review Organisational Review of Strømme Foundation Final report Norad Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation P.O. Box 8034 Dep, NO-0030 OSLO Ruseløkkveien 26, Oslo, Norway Phone: +47 22 24 20 30 Fax: +47 22 24 20 31 ISBN 978-82-7548-292-9 ISSN 1502-2528 Organisational Review of Strømme Foundation Final report 12 March 2008 Titus Tenga, LINS Roy Mersland, Nordic Consulting Group Responsibility for the contents and presentation of findings and recommendations rests with the study team. The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily correspond with those of Norad. Executive summary This report is a regular Norad organisational review of the development partner Strømme Foundation (SF). SF is a Norwegian foundation based on Christian values, with a mission to eradicate poverty. SF has a framework agreement with Norad, which was signed in 2003. The organisation will be assessed for a renewed framework agreement after the fiscal year 2008. The total annual income in 2007 was around 126 million NOK, out of which around 36 million was funded by Norad. The reason for carrying out a review now is to establish a platform for further dialogue before assessing a renewed framework agreement from 2009 onward. Another objective is to present constructive recommendations for SF’s developmental efforts. Recently a new general secretary is heading SF, replacing the former who served the organisation for more than 14 years. This shift naturally puts the organisation in a transition position. This review process thus comes timely. Microfinance and education are the main areas in SF. -

Results of Development Cooperation Through Norwegian Ngos in East Africa

Evaluation Department Results of Development Cooperation through Norwegian Ngos in East Africa Report 1/2011 – Evaluation Volume II Norad Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation P.O.Box 8034 Dep, NO-0030 Oslo Ruseløkkveien 26, Oslo, Norway Phone: +47 22 24 20 30 Fax: +47 22 24 20 31 Photos: Tanzania. Ken Opprann. Design: Agendum See Design Print: 07 Gruppen AS, Oslo ISBN: 978-82-7548-565-4 Results of Development Cooperation through Norwegian Ngos in East Africa Volume II March 2011 Ternstrom Consulting AB Results of development cooperation through Norwegian Ngos in East Africa Responsibility for the contents and presentation of findings and recommendations rest with the evaluation team. The views and opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily correspond with those of Norad. Contents List of Acronyms, Case Narratives v Volume II: Case Study Narratives 1 1 NLM/Chesta Girls School 1 2 CARE/Lok Pachi 11 3 NCA/ Habiba FGM Awareness 19 4 ARC/Change Agent Training 26 5 KF/Elimination of FGM, Dodoma 34 6 KF/Women and Health, Chole 46 7 NCA/Interfaith Cooperation 56 8 LO/ZATUC 66 9 NPA/Youth Rights EAC 74 10 SF/Microfinance 83 11 NAD/Community Based Rehabilitation 85 12 NBA/Legal Aid 95 13 NWF/Vocational Training 102 14 RB/ECDE Education 110 15 RB/Quality Education 117 Results of development cooperation through Norwegian NGOs in East Africa i List of Acronyms, Case Narratives ABEK Alternative Basic Education for Karamoja AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ARC-Aid Action Resort for Change (Norway based) ARC-Kenya Action Resort -

Evaluation of Norway's Anti-Corruption Efforts As Part of Its

EVALUATION DEPARTMENT Report 5 / 2020 ANNEX 5 Evaluation of Norway’s Anti-Corruption Efforts as part of its Development Policy and Assistance Commissioned by The Evaluation Department Carried out by Nordic Consulting Group (NCG) Written by Ch. Vaillant, M. Buch Christensen, M. Pyman, G. Sundet, L. Smed Quality assurance by O. Winckler Andersen This report is the product of the authors, and responsibility for the accuracy of data included in this report rests with the authors alone. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions presented in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Evaluation Department. September 2020 ISBN 978-82-8369-044-6 Annex 5: Case study reports 5.1 Country Case Study: Somalia 5.2 Thematic Sector Case Study: The Health Sector 5.3 Thematic Sector Case Study: Climate & Forestry 5.4 Zero-Tolerance Case Study 5.5 Global Case Study: Linking Norway’s Global Advocacy with the Development Agenda I. Country Case Study - Somalia 1 I. Country Case Study: Somalia 2 Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Limitations.............................................................................................................................. -

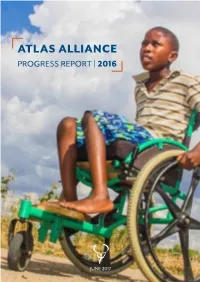

PDF of Atlas Alliance Progress Report 2016

ATLAS ALLIANCE PROGRESS REPORT | 2016 JUNE 2017 Contents Introduction . 3 The Atlas Alliance – who are we? . 4 Results 2016 Human Rights Advocacy . 8 Inclusive Education . 12 Health and Rehabilitation . 16 Economic Empowerment . 20 Malawi . 22 Nepal . 26 Uganda . 28 Zambia . 30 Mainstreaming: The Inclusion Project . 32 Advocacy in Norway . .34 . Communication . 36 Research and documentation . 37 Internal coordination and quality assurance . 38 Monitoring and evaluation . .39 . Added value . 40 Cross-cutting issues Anti-corruption . 42 Women’s rights and gender equality . 44 The environment and climate change . 47 Deviations from the plan . 48 Name of grant recipient: The Atlas Alliance Norad agreement number: QZA-15/0470 Agreement period: 2016-2019 Reporting year: 2016 PROGRESS REPORT 2016 Introduction BY ARNT HOLTE, CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD 2016 was the first year of implementing the 2030 Agenda for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – a framework that recognises meaningful participation and inclusion of persons with disability in all areas of development and economic growth . The Atlas Alliance has projects and activities contributing to reaching several of the SDGs, such as the goals on education, health and employment . The SDGs call for shared action and responsibility for inclusive development where no one is left behind . This is a vision we share with our sisters and brothers in developing countries as we fight together for inclusive societies where the needs of persons with disabilities are met and our voices heard . The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) is now ratified in 173 countries . Despite the advancement of the CRPD and human rights frameworks, there is still a lack of commitment to implementation in many of our partner countries .