Gnomon Assessment for Geographic Coordinate, Solar Horizontal & Equatorial Coordinates, Time of Local Sunrise, Noon, Sunset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing Eratosthenes' Discovery in the Classroom: Educational

Implementing Eratosthenes’ Discovery in the Classroom: Educational Difficulties Needing Attention Nicolas Decamp, C. de Hosson To cite this version: Nicolas Decamp, C. de Hosson. Implementing Eratosthenes’ Discovery in the Classroom: Educational Difficulties Needing Attention. Science and Education, Springer Verlag, 2012, 21 (6), pp.911-920. 10.1007/s11191-010-9286-3. hal-01663445 HAL Id: hal-01663445 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01663445 Submitted on 18 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sci & Educ DOI 10.1007/s11191-010-9286-3 Implementing Eratosthenes’ Discovery in the Classroom: Educational Difficulties Needing Attention Nicolas De´camp • Ce´cile de Hosson Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2010 Abstract This paper presents a critical analysis of the accepted educational use of the method performed by Eratosthenes to measure the circumference of Earth which is often considered as a relevant means of dealing with issues related to the nature of science and its history. This method relies on a number of assumptions among which the parallelism of sun rays. The assumption of sun rays parallelism (if it is accurate) does not appear spontaneous for students who consider sun rays to be divergent. -

Planetary Diagrams — Descriptions, Models, Theories: from Carolingian Deployments to Copernican Debates

Planetary Diagrams — Descriptions, Models, Theories: from Carolingian Deployments to Copernican Debates Bruce Eastwood and Gerd Graßhoff Contents 1 Introduction . 1 2 The Beginnings in Carolingian Europe . 1 2.1 Astronomy and Computus before 800 . 1 2.2 Schools and Texts . 3 2.3 Diagrams and the Study of Texts . 7 2.4 Dynamics of Diagrams: Calcidius and Pliny . 7 2.5 Dynamics of Diagrams: Martianus Capella . 21 3 Qualitative Theory in the High and Later Middle Ages . 29 3.1 Dynamics of Diagrams: Construction of a Planetary The- ory............................ 29 3.2 The Capellan Tradition through the Fifteenth Century . 32 4 Merging Two Traditions: The Sixteenth Century . 37 1 INTRODUCTION Through three distinct periods from ca. 800 to ca. 1600 we find that European as- tronomers were concerned with questions about the planets that involved the dis- cussion and invention of models without quantitative expression. This qualitative tradition was first developed in the ninth century in the course of studying ancient Latin texts on cosmology and astronomy. The diagrams, used to represent different phenomena and aspects of planetary motion, continued as long as they were found useful for teaching, for exposing questions, or for proposing theoretical positions. The history of this tradition of planetary diagrams indicates a constant concern for qualitative theory and the co-existence of both qualitative and quantitative plane- tary theory after the introduction of the Greco-Arabic mathematical tradition of planetary astronomy in twelfth-century Europe. In the sixteenth century the same qualitative tradition continued as a source for approaches to new phenomena and problems. 2 THE BEGINNINGS IN CAROLINGIAN EUROPE 2.1 ASTRONOMY AND COMPUTUS BEFORE 800 From the sixth century to the twelfth century in Western Europe there was no direct influence of Greek works in the exact sciences. -

Astronomy and Hipparchus

CHAPTER 9 Progress in the Sciences: Astronomy and Hipparchus Klaus Geus Introduction Geography in modern times is a term which covers several sub-disciplines like ecology, human geography, economic history, volcanology etc., which all con- cern themselves with “space” or “environment”. In ancient times, the definition of geography was much more limited. Geography aimed at the production of a map of the oikoumene, a geographer was basically a cartographer. The famous scientist Ptolemy defined geography in the first sentence of his Geographical handbook (Geog. 1.1.1) as “imitation through drafting of the entire known part of the earth, including the things which are, generally speaking, connected with it”. In contrast to chorography, geography uses purely “lines and label in order to show the positions of places and general configurations” (Geog. 1.1.5). Therefore, according to Ptolemy, a geographer needs a μέθοδος μαθεματική, abil- ity and competence in mathematical sciences, most prominently astronomy, in order to fulfil his task of drafting a map of the oikoumene. Given this close connection between geography and astronomy, it is not by default that nearly all ancient “geographers” (in the limited sense of the term) stood out also as astronomers and mathematicians: Among them Anaximander, Eudoxus, Eratosthenes, Hipparchus, Poseidonius and Ptolemy are the most illustrious. Apart from certain topics like latitudes, meridians, polar circles etc., ancient geography also took over from astronomy some methods like the determina- tion of the size of the earth or of celestial and terrestrial distances.1 The men- tioned geographers Anaximander, Eudoxus, Hipparchus, Poseidonius and Ptolemy even constructed instruments for measuring, observing and calculat- ing like the gnomon, sundials, skaphe, astrolabe or the meteoroscope.2 1 E.g., Ptolemy (Geog. -

A Solstice Sundial

A SOLSTICE SUNDIAL JACKIE JONES arlier this year a group of us went on holiday to It being Wales, one is never sure about the weather, so we South Wales; as the period covered the summer prepared for different methods of establishing the north– E solstice, we decided it should be celebrated in south line. In the hope of a sunny day and being able some form. Following the experience of the sundial on to draw a line from the shadow of a vertical pole, we Crosby Beach just before the BSS Conference in Liverpool calculated how solar noon would relate to watch time. in April 2016,1 I decided another seaside sundial would be Taking into account the longitude, which was 4° west appropriate. equalling 16 minutes; equation of time, dial slow by As with that event, planning the dial and exactly where it 1 minute 42 seconds and the one hour for British Summer will be, in advance, is essential. With the aid of maps and Time gave us a watch time of 13:17:42 – probably a bit Google Earth we located a south-facing sandy beach just a over-accurate for our needs. We also planned to have a few minutes’ walk from where we were staying. The compass, knowing the correction from magnetic to true latitude of the bay is 51° 34ʹ north and we agreed to north. construct a solar-time horizontal dial using only natural On a coastal walk a few days before the solstice, we found materials found nearby. Before leaving home, I drew out on the perfect long sticks needed for the gnomon and supports; metre-wide paper the layout of the afternoon hour lines for we were then fully prepared. -

The Sundial Cities

The Sundial Cities Joel Van Cranenbroeck, Belgium Keywords: Engineering survey;Implementation of plans;Positioning;Spatial planning;Urban renewal; SUMMARY When observing in our modern cities the sun shade gliding along the large surfaces of buildings and towers, an observer can notice that after all the local time could be deduced from the position of the sun. The highest building in the world - the Burj Dubai - is de facto the largest sundial ever designed. The principles of sundials can be understood most easily from an ancient model of the Sun's motion. Science has established that the Earth rotates on its axis, and revolves in an elliptic orbit about the Sun; however, meticulous astronomical observations and physics experiments were required to establish this. For navigational and sundial purposes, it is an excellent approximation to assume that the Sun revolves around a stationary Earth on the celestial sphere, which rotates every 23 hours and 56 minutes about its celestial axis, the line connecting the celestial poles. Since the celestial axis is aligned with the axis about which the Earth rotates, its angle with the local horizontal equals the local geographical latitude. Unlike the fixed stars, the Sun changes its position on the celestial sphere, being at positive declination in summer, at negative declination in winter, and having exactly zero declination (i.e., being on the celestial equator) at the equinoxes. The path of the Sun on the celestial sphere is known as the ecliptic, which passes through the twelve constellations of the zodiac in the course of a year. This model of the Sun's motion helps to understand the principles of sundials. -

9 · the Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece

9 · The Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe There is no complete break between the development of That such a change should occur is due both to po cartography in classical and in Hellenistic Greece. In litical and military factors and to cultural developments contrast to many periods in the ancient and medieval within Greek society as a whole. With respect to the world, we are able to reconstruct throughout the Greek latter, we can see how Greek cartography started to be period-and indeed into the Roman-a continuum in influenced by a new infrastructure for learning that had cartographic thought and practice. Certainly the a profound effect on the growth of formalized know achievements of the third century B.C. in Alexandria had ledge in general. Of particular importance for the history been prepared for and made possible by the scientific of the map was the growth of Alexandria as a major progress of the fourth century. Eudoxus, as we have seen, center of learning, far surpassing in this respect the had already formulated the geocentric hypothesis in Macedonian court at Pella. It was at Alexandria that mathematical models; and he had also translated his Euclid's famous school of geometry flourished in the concepts into celestial globes that may be regarded as reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 B.C.). And it anticipating the sphairopoiia. 1 By the beginning of the was at Alexandria that this Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy I Hellenistic period there had been developed not only the Soter, a companion of Alexander, had founded the li various celestial globes, but also systems of concentric brary, soon to become famous throughout the Mediter spheres, together with maps of the inhabited world that ranean world. -

Determining True North on Mars by Using a Sundial on Insight D

Determining True North on Mars by Using a Sundial on InSight D. Savoie, A. Richard, M. Goutaudier, N. Onufer, M. Wallace, D. Mimoun, K. Hurst, N. Verdier, P. Lognonné, N. Mäki, et al. To cite this version: D. Savoie, A. Richard, M. Goutaudier, N. Onufer, M. Wallace, et al.. Determining True North on Mars by Using a Sundial on InSight. Space Science Reviews, Springer Verlag, 2019, 215 (1), pp.215:2. hal-01977462 HAL Id: hal-01977462 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01977462 Submitted on 10 Jan 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Determining true North on Mars by using a sundial on InSight D. Savoiea,∗, A. Richardb,∗∗, M. Goutaudierb, N.P. Onuferc, M.C. Wallacec, D. Mimoune, K. Hurstc, N. Verdierf, P. Lognonnéd, J.N. Makic, B. Banerdtc aSYRTE, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, LNE, 61 avenue de l’Observatoire 75014 Paris, France bPalais de la Découverte, Av. Franklin D. Roosevelt, 75008 Paris, France cNASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California dInstitut de Physique du Globe de Paris, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France eInstitut Supérieur de l’Aéronautique et de l’Espace, ISAE, Toulouse, France fFrench National Space Agency, CNES, Paris, France Abstract In this work, we demonstrate the possibility to determine the true North direction on Mars by using a gnomon on the InSight mission. -

How Big Is the Earth?

Document ID: 04_01_13_1 Date Received: 2013-04-01 Date Revised: 2013-07-24 Date Accepted: 2013-08-16 Curriculum Topic Benchmarks: M4.4.8, M5.4.12, M8.4.2, M8.4.15, S15.4.4, S.16.4.1, S16.4.3 Grade Level: High School [9-12] Subject Keywords: circumference, radius, Eratosthenes, gnomon, sun dial, Earth, noon, time zone, latitude, longitude, collaboration Rating: Advanced How Big Is the Earth? By: Stephen J Edberg, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, M/S 183-301, Pasadena CA 91011 e-mail: [email protected] From: The PUMAS Collection http://pumas.jpl.nasa.gov ©2013, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Eratosthenes, the third librarian of the Great Library of Alexandria, measured the circumference of Earth around 240 B.C.E. Having learned that the Sun passed through the zenith1 on the summer solstice2 as seen in modern day Aswan, he measured the length of a shadow on the solstice in Alexandria. By converting the measurement to an angle he determined the difference in latitude – what fraction of a circle spanned the separation – between Aswan and Alexandria. Knowing the physical distance between Aswan and Alexandria allowed him to determine the circumference of Earth. Cooperating schools can duplicate Eratosthenes’ measurements without the use of present day technology, if desired. Sharing their data permits students to calculate the circumference and the radius of Earth. The measurements do not require a site on the Tropic of Cancer (or the Tropic of Capricorn) but they must be made at local solar noon on the same date. -

1 TITLE: World According to Dicæarchus DATE: 300 BC AUTHOR

World view according to Dicæarchus #111 TITLE: World according to Dicæarchus DATE: 300 B.C. AUTHOR: Dicæarchus of Messana DESCRIPTION: Pytheas (ca. 320-305), a contemporary of Alexander the Great, is significant for extending geographic knowledge of Western Europe, especially the coasts along the English Channel, and for his use of astronomical observations to compute latitudes. A navigator and astronomer from the Greek colony of Massalia [Marseilles], he explored the Ocean west of the European mainland and recorded his journey and observations in the work entitled On the Ocean, now lost but quoted and criticized by Strabo. Pytheas’ claim to have explored “in person” the entire northern region of Europe “as far as the ends of the world” met with disbelief by Strabo who accused him of shameless mendacity. Nonetheless, other writers used his observations. Most modern scholars agree that his journey in fact occurred, yet there is no consensus regarding its date or time or scope—perhaps reaching to islands north of Scotland, to Norway, to Jutland, or even to Iceland. Pytheas sailed from Massalia through the Pillars of Hercules {Straits of Gibraltar] up the Iberian coast to the Tin Islands (Cassiterges, whose location is contested) and across to Britain; next probably the coast to Scotland, its Northern Isles, and the island of Thule; then back east to the Baltic, where he found the source of amber on the island of Abalus. He described Britain as a triangle, and with reasonable accuracy he estimated the island’s circumference at more than 40,000 stadia, a length considered excessive by Strabo but accepted by Eratosthenes. -

11 · the Culmination of Greek Cartography in Ptolemy

11 · The Culmination of Greek Cartography in Ptolemy o. A. w. DILKE WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL SUPPLIED BY THE EDITORS By the time of Marinus of Tyre (fl. A.D. 100) and Clau about his work remain unanswered. Little is known dius Ptolemy (ca. A.D. 90-168), Greek and Roman in about Ptolemy the man, and neither his birthplace nor fluences in cartography had been fused to a considerable his dates have been positively established.4 Moreover, extent into one tradition. There is a case, accordingly, in relation to the cartographic component in his writings, for treating them as a history of one already unified we must remember that no manuscript earlier than the stream of thought and practice. Here, however, though twelfth century A.D. has come down to us, and there is we accept that such a unity exists, the discussion is fo no adequate modern translation and critical edition of cused on the cartographic contributions of Marinus and the Geography.5 Perhaps most serious of all for the stu Ptolemy, both writing in Greek within the institutions dent of mapping, however, is the whole debate about of Roman society. Both men owed much to Roman the true authorship and provenance of the general and sources of information and to the extension ofgeograph regional maps that accompany the several versions of ical knowledge under the growing empire: yet equally, the Byzantine manuscripts (pp. 268-74 below). AI- in the case of Ptolemy especially, they represent a cul mination as well as a final synthesis of the scientific tradition in Greek cartography that has been traced through a succession of writers in the previous three 1. -

Armillary Sphere (1:1)

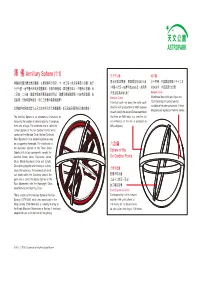

ìMň Armillary Sphere (1:1) P7 GɌ Ɍ ìň͈éƼP͵˲ɗňˢľ:C?·XZ#Z9YŹXŹ·:ň%P ˊ9˥ɚƮoŅ=ϝŋ@365¼̑ 8oXƷ=ŋV°PVLc 7 GɌZɌůPʂčͦɌ:5o+βϏľŶƙ˲dz͔\#Ź·Yēň% #ɍD(ƙE ł-·365¼̀ɰŲ S9Ʒ=ŋ?ϟ LɌZL?ɌZͥ˛čͦɌůǩͦɌľ`5̌͵Cūɫƭ˛ƕ9Ź·Vͥň% PRȓƙ·365¼̑ Horizon Circle A horizontal ring with 4 wei, 8 gan and VͥoZPƭů͛Ͳ5CYēň9ūɫƭ˛ƕ Meridian Circle A vertical split ring along the north-south 12 zhi (totalling 24 cardinal points) Fìň͈ȴʙˊĭŁʔP~RɗǺ(=7ìňɒçĦµ̮ʌ"dzGÓɗȜ̑ direction with graduations of 365¼ degrees inscribed on the outer surface and 12 fenye on each side (As the ancient Chinese determined (kingdoms and regions) on the inner surface The Armillary Sphere is an astronomical instrument for that there are 365¼ days in a year, the full measuring the position of celestial objects. It comprises circumference of the sky is assigned as three sets of rings. The outermost one is called the 365¼ degrees) Liuheyi (Sphere of the Six Cardinal Points) which consists of the Meridian Circle, Horizon Circle and Fixed Equatorial Circle welded together securely on a supporting framework. The middle one is :ň the Sanchenyi (Sphere of the Three Stellar Objects) with its four components, namely, the Sphere of the Solstitial Colure Circle, Equinoctial Colure Six Cardinal Points Circle, Mobile Equatorial Circle and Ecliptic Circle joining together and rotating as a whole PʂčͦɌ around the polar axis. The innermost set which can rotate within the Sanchenyi around the .P̸čͦ polar axis is called the Siyouyi (Sphere of the \ŋVLòēEWŋ Four Movements) with the Hour-angle Circle, ̀XWŋo Celestial Axis and Sighting Tube. -

Hipparchus's Table of Chords

ApPENDIX 1 Hipparchus's Table of Chords The construction of this table is based on the facts that the chords of 60° and 90° are known, that starting from chd 8 we can calculate chd(180° - 8) as shown by Figure Al.1, and that from chd S we can calculate chd ~8. The calculation of chd is goes as follows; see Figure Al.2. Let the angle AOB be 8. Place F so that CF = CB, place D so that DOA = i8, and place E so that DE is perpendicular to AC. Then ACD = iAOD = iBOD = DCB making the triangles BCD and DCF congruent. Therefore DF = BD = DA, and so EA = iAF. But CF = CB = chd(180° - 8), so we can calculate CF, which gives us AF and EA. Triangles AED and ADC are similar; therefore ADIAE = ACIDA, which implies that AD2 = AE·AC and enables us to calculate AD. AD is chd i8. We can now find the chords of 30°, 15°, 7~0, 45°, and 22~0. This gives us the chords of 150°, 165°, etc., and eventually we have the chords of all R P chord 8 = PQ, C chord (180 - 8) = QR, QR2 = PR2 _ PQ2. FIGURE A1.l. 235 236 Appendix 1. Hipparchus's Table of Chords Ci"=:...-----""----...........~A FIGURE A1.2. multiples of 71°. The table starts: 2210 10 8 2 30° 45° 522 chd 8 1,341 1,779 2,631 3,041 We find the chords of angles not listed and angles whose chords are not listed by linear interpolation. For example, the angle whose chord is 2,852 is ( 2,852 - 2,631 1)0 .