Iterative & Evolutionary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Timeboxing Process Model for Iterative Software Development

The Timeboxing Process Model for Iterative Software Development Pankaj Jalote Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur – 208016; India Aveejeet Palit, Priya Kurien Infosys Technologies Limited Electronics City Bangalore – 561 229; India Contact: [email protected] ABSTRACT In today’s business where speed is of essence, an iterative development approach that allows the functionality to be delivered in parts has become a necessity and an effective way to manage risks. In an iterative process, the development of a software system is done in increments, each increment forming of an iteration and resulting in a working system. A common iterative approach is to decide what should be developed in an iteration and then plan the iteration accordingly. A somewhat different iterative is approach is to time box different iterations. In this approach, the length of an iteration is fixed and what should be developed in an iteration is adjusted to fit the time box. Generally, the time boxed iterations are executed in sequence, with some overlap where feasible. In this paper we propose the timeboxing process model that takes the concept of time boxed iterations further by adding pipelining concepts to it for permitting overlapped execution of different iterations. In the timeboxing process model, each time boxed iteration is divided into equal length stages, each stage having a defined function and resulting in a clear work product that is handed over to the next stage. With this division into stages, pipelining concepts are employed to have multiple time boxes executing concurrently, leading to a reduction in the delivery time for product releases. -

Agile Playbook V2.1—What’S New?

AGILE P L AY B O OK TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................4 Who should use this playbook? ................................................................................6 How should you use this playbook? .........................................................................6 Agile Playbook v2.1—What’s new? ...........................................................................6 How and where can you contribute to this playbook?.............................................7 MEET YOUR GUIDES ...................................................................................................8 AN AGILE DELIVERY MODEL ....................................................................................10 GETTING STARTED.....................................................................................................12 THE PLAYS ...................................................................................................................14 Delivery ......................................................................................................................15 Play: Start with Scrum ...........................................................................................15 Play: Seeing success but need more fexibility? Move on to Scrumban ............17 Play: If you are ready to kick of the training wheels, try Kanban .......................18 Value ......................................................................................................................19 -

Descriptive Approach to Software Development Life Cycle Models

7797 Shaveta Gupta et al./ Elixir Comp. Sci. & Engg. 45 (2012) 7797-7800 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Computer Science and Engineering Elixir Comp. Sci. & Engg. 45 (2012) 7797-7800 Descriptive approach to software development life cycle models Shaveta Gupta and Sanjana Taya Department of Computer Science and Applications, Seth Jai Parkash Mukand Lal Institute of Engineering & Technology, Radaur, Distt. Yamunanagar (135001), Haryana, India. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The concept of system lifecycle models came into existence that emphasized on the need to Received: 24 January 2012; follow some structured approach towards building new or improved system. Many models Received in revised form: were suggested like waterfall, prototype, rapid application development, V-shaped, top & 17 March 2012; Bottom model etc. In this paper, we approach towards the traditional as well as recent Accepted: 6 April 2012; software development life cycle models. © 2012 Elixir All rights reserved. Keywords Software Development Life Cycle, Phases and Software Development, Life Cycle Models, Traditional Models, Recent Models. Introduction Software Development Life Cycle Models The Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) is the entire Software Development Life Cycle Model is an abstract process of formal, logical steps taken to develop a software representation of a development process. SDLC models can be product. Within the broader context of Application Lifecycle categorized as: Management (ALM), the SDLC -

Ovum Decision Matrix: Selecting an Application Lifecycle Management and Devops Solution, 2019–20

Ovum Decision Matrix: Selecting an Application Lifecycle Management and DevOps Solution, 2019–20 Publication Date: 27 Jun 2019 | Product code: INT003-000374 Michael Azoff Ovum Decision Matrix: Selecting an Application Lifecycle Management and DevOps Solution, 2019–20 Summary Catalyst Software lifecycle management (SLM) is the management of software development by taking a lifecycle approach from concept through the management of requirements, testing, coding, deployment, upgrades, maintenance, and final retirement. The market provides tools to support this lifecycle in the form of application lifecycle management (ALM) tools and, with the rise of DevOps, tools that provide DevOps-style release management, orchestration, and automation. This Ovum Decision Matrix (ODM) examines ALM tools that cross over into DevOps to support the full arc of the lifecycle from application/product concept to deployment into production. Ovum view ALM origins and trends The need for taking an SLM approach is best thought of as good practice in the relatively young art of software development. The ALM tools market has evolved to support SLM through the years; at its core is the development methodology or work process, and this has evolved over time, starting with waterfall or linear stage-gate processes and incorporating various innovations such as Tom Gilb's evolutionary delivery, Barry Boehm's spiral model, and Rational's unified process, before Agile and lean swept the board with examples such as Scrum, extreme programming, and Kanban boards post- 2001 (when the Agile Manifesto was created). The integrated ALM suite tools market really took off around 2003 but supported waterfall because Agile was still under the radar. -

A Comparison Between Five Models of Software Engineering

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 7, Issue 5, September 2010 94 ISSN (Online): 1694-0814 www.IJCSI.org A Comparison Between Five Models Of Software Engineering Nabil Mohammed Ali Munassar1 and A. Govardhan2 1Ph.D Student of Computer Science & Engineering Jawahrlal Nehru Technological University Kuktapally, Hyderabad- 500 085, Andhra Pradesh, India 2Professor of Computer Science & Engineering Principal JNTUH of Engineering College, Jagityal, Karimnagar (Dt), A.P., India Abstract increased recently which results in the difficulty of This research deals with a vital and important issue in computer enumerating such companies. During the previous four world. It is concerned with the software management processes decades, software has been developed from a tool used for that examine the area of software development through the analyzing information or solving a problem to a product in development models, which are known as software development itself. However, the early programming stages have life cycle. It represents five of the development models namely, created a number of problems turning software an waterfall, Iteration, V-shaped, spiral and Extreme programming. These models have advantages and disadvantages as well. obstacle to software development particularly those Therefore, the main objective of this research is to represent relying on computers. Software consists of documents and different models of software development and make a programs that contain a collection that has been comparison between them to show the features and defects of established to be a part of software engineering each model. procedures. Moreover, the aim of software engineering is Keywords: Software Management Processes, Software to create a suitable work that construct programs of high Development, Development Models, Software Development Life quality. -

Software Development a Practical Approach!

Software Development A Practical Approach! Hans-Petter Halvorsen https://www.halvorsen.blog https://halvorsen.blog Software Development A Practical Approach! Hans-Petter Halvorsen Software Development A Practical Approach! Hans-Petter Halvorsen Copyright © 2020 ISBN: 978-82-691106-0-9 Publisher Identifier: 978-82-691106 https://halvorsen.blog ii Preface The main goal with this document: • To give you an overview of what software engineering is • To take you beyond programming to engineering software What is Software Development? It is a complex process to develop modern and professional software today. This document tries to give a brief overview of Software Development. This document tries to focus on a practical approach regarding Software Development. So why do we need System Engineering? Here are some key factors: • Understand Customer Requirements o What does the customer needs (because they may not know it!) o Transform Customer requirements into working software • Planning o How do we reach our goals? o Will we finish within deadline? o Resources o What can go wrong? • Implementation o What kind of platforms and architecture should be used? o Split your work into manageable pieces iii • Quality and Performance o Make sure the software fulfills the customers’ needs We will learn how to build good (i.e. high quality) software, which includes: • Requirements Specification • Technical Design • Good User Experience (UX) • Improved Code Quality and Implementation • Testing • System Documentation • User Documentation • etc. You will find additional resources on this web page: http://www.halvorsen.blog/documents/programming/software_engineering/ iv Information about the author: Hans-Petter Halvorsen The author currently works at the University of South-Eastern Norway. -

Software Maintenance Lifecycle Modeling

Home Software Maintenance Lifecycle Modeling D Vijay Rao, VVS Sarma and NK Srinivasan Department of Computer Science & Automation Indian Institute of Science Bangalore 560 012, India. Abstract Maintenance of legacy systems, representing a massive, long-term business investment, is an important but relatively new research area. A generic, unified lifecycle model (ULM) integrating the product, process and project views of software development and maintenance based on re- entrant lines is proposed. The proposed re-entrant line model represents the software maintenance process in a software organisation. The existing model for software development predicts project metrics such as the development time, cost and product quality for any new project to be taken up by the organization. The routing matrix of the artifacts in the ULM can be modified to derive different types of lifecycle models such as Waterfall, Prototyping, Spiral and Hybrid models. The ULM is modified to depict the complex set of activities associated with software maintenance. Quantitative metrics such as release time of versions, cost, time and effort for maintenance are estimated using this model. 1. Introduction The area of software maintenance has not received adequate attention in the literature because it was considered as a fairly routine activity with no challenge for creative people. Today, when salaries of programmers have become a major part of the data processing budget, the difficulties in software maintenance are slowly becoming apparent. A large proportion of the software products in operation are the so-called ‘legacy systems’ [TrTi95, LLFG97, BMW96, BM97]. Such systems, that typically are the backbone of an organization’s information flow and business, represent a massive, long-term business investment. -

SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT MODELS and THEIR REAL ASPECTS Divya Tanwar Sbs , Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, GGSIPU, Delhi

SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT MODELS AND THEIR REAL ASPECTS Divya Tanwar Sbs , Vivekananda Institute of Professional Studies, GGSIPU, Delhi ABSTRACT Software development life cycle models are the most integral part when it comes to software development which can fully justify today’s digitally environments with increasing mobile, web, and desktop applications. This research deals with a vital and important issue in information technology with respect to various models used in development. It is concerned with the software management processes that examine the area of software development through the development models, which are known as software development life cycle. It represents five of the development models namely, waterfall, Iteration, prototype and spiral and their real time examples which we can relate in our day to day life. These models are complex and difficult to identify related to real time scenario. Therefore, the main objective of this research is to represent different models of software development and make a comparison between them to show the features and defects of each model. This paper demystifies these concepts so that the SDLC is correctly understood with their real time. Keywords: Iterative Prototyping SDLC, Software development life cycle, Spiral model, Real aspects, Waterfall model I. INTRODUCTION Software development life cycle models are the important part of the Software Engineering which is a discipline whose aim to develop quality software, which is on time, with minimum cost and can satisfy the organization needs. There are basically four main models in SDLC with different characteristics and drawbacks [2] .The most difficult task is to identify the model which suits the organization structure, for this every organization need to know the model and its real time application so the user can relate, understand and find out how its actually working. -

Strengths and Weakness of Traditional and Agile Processes a Systematic Review

Journal of Software Strengths and Weakness of Traditional and Agile Processes A Systematic Review Mahrukh Sameen Mirza, Soma Datta* University of Houston-Clear Lake, Houston, Texas, USA. * Corresponding author. Tel.: 12182833838 email: [email protected], [email protected] Manuscript submitted February 25, 2019; accepted April 10, 2019. doi: 10.17706/jsw.14.5.209-219 Abstract: In the software industry, there are several processes and methodologies that exist. The traditional processes and Agile methodologies have their own strengths and weaknesses. Agile methodologies overcome some of the weaknesses of traditional processes. Although in the recent years Agile methodologies have been used by software development companies, there is still a high ratio of software failures when compared with core engineering processes. The adoption of these processes in software development could alleviate software failures. This systematic study reviews the strengths and weaknesses of both traditional processes and Agile processes. The search strategy resulted in 91 papers, of which 25 primary studies are investigated between 2012 and 2019. The detailed search strategy has been presented in this study along with future directions. Key words: Agile, core engineering processes, extreme programming, feature driven development, Kanban, lean, scrum, systematic review, test driven development, traditional. 1. Introduction Before 2001[1]-[13], the software industry used traditional software development processes (i.e., Classical waterfall model, iterative waterfall model, spiral model, RAD model). While these traditional models are known to be cost saving for bigger, off-shore projects, there is criticism that exists [13]-[25]. Due to these criticisms and the high ratio of software failures that used traditional models, it led to a change in software process development in 1999. -

A Spiral Model of Software Development and Enhancement

A Spiral Model of Software Development and Enhancement Barry W. Boehm, TRW Defense Systems Group “Stop the life cycle-I want to get off!’’ criteria for the current stage plus choice “Life-cycle Concept Considered criteria and entrance criteria for the next Harmful. ” stage. Thus, a process model addresses the “The waterfall model is dead.” This evolving- risk- following software project questions: “No, it isn’t, but it should be.” (1) What shall we do next? driven approach (2) How long shall we continue to do it? hese statements exemplify the provides a new Consequently, a process model differs current debate about software from a software method (often called a Iife-cycle process models. The framework for guiding T methodology) in that a method’s primary topic has recently received a great deal of the software process. focus is on how to navigate through each attention. phase (determining data, control, or The Defense Science Board Task Force ‘‘uses” hierarchies; partitioning functions; Report on Military Software‘ issued in allocating requirements) and how to rep- 1987 highlighted the concern that tradi- resent phase products (structure charts; tional software process models were dis- stimulus-response threads; state transition couraging more effective approaches to diagrams). software development such as prototyping Why are software process models and software reuse. The Computer Soci- spiral model; illustrate the application of the spiral model to a software project, important? Primarily because they pro- ety has sponsored tutorials and workshops vide guidance on the order (phases, incre- on software process models that have using the TRW Software Productivity Project as an example; summarize the pri- ments, prototypes, validation tasks, etc.) helped clarify many of the issues and in which a project should carry out its stimulated advances in the field (see “Fur- mary advantages and implications involved in using the spiral model and the major tasks. -

Spiral Model: Advantages and Disadvantages

SPIRAL MODEL: ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES What is the Spiral Model? The Spiral Life Cycle Model is a type of iterative software development model which is generally implemented in high risk projects. It was first proposed by Boehm. In this system development method, we combine the features of both, waterfall model and prototype model. In Spiral model we can arrange all the activities in the form of a spiral. Each loop in a spiral represents a development phase (and we can have any number of loops according to the project). Each loop has four sections or quadrants : 1. To determine the objectives, alternatives and constraints. We try to understand the product objectives, alternatives in design and constraints imposed because of cost, technology, schedule, etc. 2. Risk analysis and evaluation of alternatives. Here we try to find which other approaches can be implemented in order to fulfill the identified constraints. Operational and technical issues are addressed here. Risk mitigation is in focus in this phase. And evaluation of all these factors determines future action. 3. Execution of that phase of development. In this phase we develop the planned product. Testing is also done. In order to do development, waterfall or incremental approach can be implemented. 4. Planning the next phase. Here we review the progress and judge it considering all parameters. Issues which need to be resolved are identified in this phase and necessary steps are taken. Subsequent loops of spiral model involve similar phases. Analysis and engineering efforts are applied in this model. Large, expensive or complicated projects use this type of life cycle. -

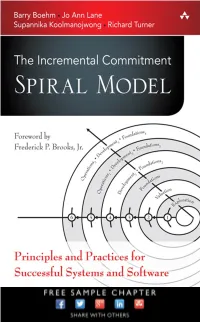

The Incremental Commitment Spiral Model: Principles and Practices for Successful Systems and Software

The Incremental Commitment Spiral Model: Phased View Stage II: Stage I: Incremental Definition Incremental Development, Operations and Production ICSM Anchor OCR1 ... ECR VCR FCR DCR1 DCR Points 2 1 1 Operations 2 1 2 ... ICSM Life-Cycle and Production(O&P) Phases Exploration Valuation Foundations Development 3 Foundations Development Foundations Activities Concurrent risk- and Initial scoping Concept System life-cycle Increment 1 Increment 1 opportunity-driven definition architecture and Development Operations and growth of system Investment ops concept Increment 2 Production understanding and analysis Build-to Foundations Increment 2 ... definition increment plans rebaseline Development and specifications Increment 3 NDI, outsource Foundations partner selections rebaseline Evaluation of evidence Feasibility ... ... ... ... ... of feasibility to proceed Evidence Stakeholder review High, but Acceptable and commitment addressable Too high, Risk? Risk? Risk? Risk? Risk? unaddressable Negligible Adjust scope, priorities, or discontinue Exploration Valuation Foundations Development Operations OCR ECR = Commitment VCR = Commitment FCR = Commitment DCRn = Commitment n = Commitment Review Review Review Reviewn Reviewn Reprinted with permission from Human-System Integration in the System Development Process, 2007 by the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. Feasibility Evidence Description Content Evidence provided by the developer and validated by independent experts that, if the system is built