Arxiv:2009.05627V2 [Math.GR] 27 Dec 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relations on Semigroups

International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM) ISSN : 2454-9150 Vol-04, Issue-09, Dec 2018 Relations on Semigroups 1D.D.Padma Priya, 2G.Shobhalatha, 3U.Nagireddy, 4R.Bhuvana Vijaya 1 Sr.Assistant Professor, Department of Mathematics, New Horizon College Of Engineering, Bangalore, India, Research scholar, Department of Mathematics, JNTUA- Anantapuram [email protected] 2Professor, Department of Mathematics, SKU-Anantapuram, India, [email protected] 3Assistant Professor, Rayalaseema University, Kurnool, India, [email protected] 4Associate Professor, Department of Mathematics, JNTUA- Anantapuram, India, [email protected] Abstract: Equivalence relations play a vital role in the study of quotient structures of different algebraic structures. Semigroups being one of the algebraic structures are sets with associative binary operation defined on them. Semigroup theory is one of such subject to determine and analyze equivalence relations in the sense that it could be easily understood. This paper contains the quotient structures of semigroups by extending equivalence relations as congruences. We define different types of relations on the semigroups and prove they are equivalence, partial order, congruence or weakly separative congruence relations. Keywords: Semigroup, binary relation, Equivalence and congruence relations. I. INTRODUCTION [1,2,3 and 4] Algebraic structures play a prominent role in mathematics with wide range of applications in science and engineering. A semigroup -

Binary Relations and Functions

Harvard University, Math 101, Spring 2015 Binary relations and Functions 1 Binary Relations Intuitively, a binary relation is a rule to pair elements of a sets A to element of a set B. When two elements a 2 A is in a relation to an element b 2 B we write a R b . Since the order is relevant, we can completely characterize a relation R by the set of ordered pairs (a; b) such that a R b. This motivates the following formal definition: Definition A binary relation between two sets A and B is a subset of the Cartesian product A×B. In other words, a binary relation is an element of P(A × B). A binary relation on A is a subset of P(A2). It is useful to introduce the notions of domain and range of a binary relation R from a set A to a set B: • Dom(R) = fx 2 A : 9 y 2 B xRyg Ran(R) = fy 2 B : 9 x 2 A : xRyg. 2 Properties of a relation on a set Given a binary relation R on a set A, we have the following definitions: • R is transitive iff 8x; y; z 2 A :(xRy and yRz) =) xRz: • R is reflexive iff 8x 2 A : x Rx • R is irreflexive iff 8x 2 A : :(xRx) • R is symmetric iff 8x; y 2 A : xRy =) yRx • R is asymmetric iff 8x; y 2 A : xRy =):(yRx): 1 • R is antisymmetric iff 8x; y 2 A :(xRy and yRx) =) x = y: In a given set A, we can always define one special relation called the identity relation. -

Semiring Orders in a Semiring -.:: Natural Sciences Publishing

Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 6, No. 1, 99-102 (2012) 99 Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences An International Journal °c 2012 NSP Natural Sciences Publishing Cor. Semiring Orders in a Semiring Jeong Soon Han1, Hee Sik Kim2 and J. Neggers3 1 Department of Applied Mathematics, Hanyang University, Ahnsan, 426-791, Korea 2 Department of Mathematics, Research Institute for Natural Research, Hanyang University, Seoal, Korea 3 Department of Mathematics, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487-0350, U.S.A Received: Received May 03, 2011; Accepted August 23, 2011 Published online: 1 January 2012 Abstract: Given a semiring it is possible to associate a variety of partial orders with it in quite natural ways, connected with both its additive and its multiplicative structures. These partial orders are related among themselves in an interesting manner is no surprise therefore. Given particular types of semirings, e.g., commutative semirings, these relationships become even more strict. Finally, in terms of the arithmetic of semirings in general or of some special type the fact that certain pairs of elements are comparable in one of these orders may have computable and interesting consequences also. It is the purpose of this paper to consider all these aspects in some detail and to obtain several results as a consequence. Keywords: semiring, semiring order, partial order, commutative. The notion of a semiring was first introduced by H. S. they are equivalent (see [7]). J. Neggers et al. ([5, 6]) dis- Vandiver in 1934, but implicitly semirings had appeared cussed the notion of semiring order in semirings, and ob- earlier in studies on the theory of ideals of rings ([2]). -

On Tarski's Axiomatization of Mereology

On Tarski’s Axiomatization of Mereology Neil Tennant Studia Logica An International Journal for Symbolic Logic ISSN 0039-3215 Volume 107 Number 6 Stud Logica (2019) 107:1089-1102 DOI 10.1007/s11225-018-9819-3 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Nature B.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self-archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Neil Tennant On Tarski’s Axiomatization of Mereology Abstract. It is shown how Tarski’s 1929 axiomatization of mereology secures the re- flexivity of the ‘part of’ relation. This is done with a fusion-abstraction principle that is constructively weaker than that of Tarski; and by means of constructive and relevant rea- soning throughout. We place a premium on complete formal rigor of proof. Every step of reasoning is an application of a primitive rule; and the natural deductions themselves can be checked effectively for formal correctness. Keywords: Mereology, Part of, Reflexivity, Tarski, Axiomatization, Constructivity. -

Functions, Sets, and Relations

Sets A set is a collection of objects. These objects can be anything, even sets themselves. An object x that is in a set S is called an element of that set. We write x ∈ S. Some special sets: ∅: The empty set; the set containing no objects at all N: The set of all natural numbers 1, 2, 3, … (sometimes, we include 0 as a natural number) Z: the set of all integers …, -3, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, 3, … Q: the set of all rational numbers (numbers that can be written as a ratio p/q with p and q integers) R: the set of real numbers (points on the continuous number line; comprises the rational as well as irrational numbers) When all elements of a set A are elements of set B as well, we say that A is a subset of B. We write this as A ⊆ B. When A is a subset of B, and there are elements in B that are not in A, we say that A is a strict subset of B. We write this as A ⊂ B. When two sets A and B have exactly the same elements, then the two sets are the same. We write A = B. Some Theorems: For any sets A, B, and C: A ⊆ A A = B if and only if A ⊆ B and B ⊆ A If A ⊆ B and B ⊆ C then A ⊆ C Formalizations in first-order logic: ∀x ∀y (x = y ↔ ∀z (z ∈ x ↔ z ∈ y)) Axiom of Extensionality ∀x ∀y (x ⊆ y ↔ ∀z (z ∈ x → z ∈ y)) Definition subset Operations on Sets With A and B sets, the following are sets as well: The union A ∪ B, which is the set of all objects that are in A or in B (or both) The intersection A ∩ B, which is the set of all objects that are in A as well as B The difference A \ B, which is the set of all objects that are in A, but not in B The powerset P(A) which is the set of all subsets of A. -

Order Relations and Functions

Order Relations and Functions Problem Session Tonight 7:00PM – 7:50PM 380-380X Optional, but highly recommended! Recap from Last Time Relations ● A binary relation is a property that describes whether two objects are related in some way. ● Examples: ● Less-than: x < y ● Divisibility: x divides y evenly ● Friendship: x is a friend of y ● Tastiness: x is tastier than y ● Given binary relation R, we write aRb iff a is related to b by relation R. Order Relations “x is larger than y” “x is tastier than y” “x is faster than y” “x is a subset of y” “x divides y” “x is a part of y” Informally An order relation is a relation that ranks elements against one another. Do not use this definition in proofs! It's just an intuition! Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 1 ≤ 5 and 5 ≤ 8 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 1 ≤ 5 and 5 ≤ 8 1 ≤ 8 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 42 ≤ 99 and 99 ≤ 137 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 42 ≤ 99 and 99 ≤ 137 42 ≤ 137 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y x ≤ y and y ≤ z Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y x ≤ y and y ≤ z x ≤ z Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y x ≤ y and y ≤ z x ≤ z Transitivity Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 1 ≤ 1 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 42 ≤ 42 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 137 ≤ 137 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y x ≤ x Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y x ≤ x Reflexivity Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 19 ≤ 21 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 19 ≤ 21 21 ≤ 19? Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 19 ≤ 21 21 ≤ 19? Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 42 ≤ 137 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 42 ≤ 137 137 ≤ 42? Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 42 ≤ 137 137 ≤ 42? Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 137 ≤ 137 Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 137 ≤ 137 137 ≤ 137? Properties of Order Relations x ≤ y 137 ≤ 137 137 ≤ 137 Antisymmetry A binary relation R over a set A is called antisymmetric iff For any x ∈ A and y ∈ A, If xRy and y ≠ x, then yRx. -

Partial Orders — Basics

Partial Orders — Basics Edward A. Lee UC Berkeley — EECS EECS 219D — Concurrent Models of Computation Last updated: January 23, 2014 Outline Sets Join (Least Upper Bound) Relations and Functions Meet (Greatest Lower Bound) Notation Example of Join and Meet Directed Sets, Bottom Partial Order What is Order? Complete Partial Order Strict Partial Order Complete Partial Order Chains and Total Orders Alternative Definition Quiz Example Partial Orders — Basics Sets Frequently used sets: • B = {0, 1}, the set of binary digits. • T = {false, true}, the set of truth values. • N = {0, 1, 2, ···}, the set of natural numbers. • Z = {· · · , −1, 0, 1, 2, ···}, the set of integers. • R, the set of real numbers. • R+, the set of non-negative real numbers. Edward A. Lee | UC Berkeley — EECS3/32 Partial Orders — Basics Relations and Functions • A binary relation from A to B is a subset of A × B. • A partial function f from A to B is a relation where (a, b) ∈ f and (a, b0) ∈ f =⇒ b = b0. Such a partial function is written f : A*B. • A total function or just function f from A to B is a partial function where for all a ∈ A, there is a b ∈ B such that (a, b) ∈ f. Edward A. Lee | UC Berkeley — EECS4/32 Partial Orders — Basics Notation • A binary relation: R ⊆ A × B. • Infix notation: (a, b) ∈ R is written aRb. • A symbol for a relation: • ≤⊂ N × N • (a, b) ∈≤ is written a ≤ b. • A function is written f : A → B, and the A is called its domain and the B its codomain. -

Binary Relations Part One

Binary Relations Part One Outline for Today ● Binary Relations ● Reasoning about connections between objects. ● Equivalence Relations ● Reasoning about clusters. ● A Fundamental Theorem ● How do we know we have the “right” defnition for something? Relationships ● In CS103, you've seen examples of relationships ● between sets: A ⊆ B ● between numbers: x < y x ≡ₖ y x ≤ y ● between people: p loves q ● Since these relations focus on connections between two objects, they are called binary relations. ● The “binary” here means “pertaining to two things,” not “made of zeros and ones.” What exactly is a binary relation? R a b aRb R a b aR̸b Binary Relations ● A binary relation over a set A is a predicate R that can be applied to pairs of elements drawn from A. ● If R is a binary relation over A and it holds for the pair (a, b), we write aRb. 3 = 3 5 < 7 Ø ⊆ ℕ ● If R is a binary relation over A and it does not hold for the pair (a, b), we write aR̸b. 4 ≠ 3 4 <≮ 3 ℕ ⊆≮ Ø Properties of Relations ● Generally speaking, if R is a binary relation over a set A, the order of the operands is signifcant. ● For example, 3 < 5, but 5 <≮ 3. ● In some relations order is irrelevant; more on that later. ● Relations are always defned relative to some underlying set. ● It's not meaningful to ask whether ☺ ⊆ 15, for example, since ⊆ is defned over sets, not arbitrary objects. Visualizing Relations ● We can visualize a binary relation R over a set A by drawing the elements of A and drawing a line between an element a and an element b if aRb is true. -

Section 4.1 Relations

Binary Relations (Donny, Mary) (cousins, brother and sister, or whatever) Section 4.1 Relations - to distinguish certain ordered pairs of objects from other ordered pairs because the components of the distinguished pairs satisfy some relationship that the components of the other pairs do not. 1 2 The Cartesian product of a set S with itself, S x S or S2, is the set e.g. Let S = {1, 2, 4}. of all ordered pairs of elements of S. On the set S x S = {(1, 1), (1, 2), (1, 4), (2, 1), (2, 2), Let S = {1, 2, 3}; then (2, 4), (4, 1), (4, 2), (4, 4)} S x S = {(1, 1), (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 1), (2, 2), (2, 3), (3, 1), (3, 2) , (3, 3)} For relationship of equality, then (1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3) would be the A binary relation can be defined by: distinguished elements of S x S, that is, the only ordered pairs whose components are equal. x y x = y 1. Describing the relation x y if and only if x = y/2 x y x < y/2 For relationship of one number being less than another, we Thus (1, 2) and (2, 4) satisfy . would choose (1, 2), (1, 3), and (2, 3) as the distinguished ordered pairs of S x S. x y x < y 2. Specifying a subset of S x S {(1, 2), (2, 4)} is the set of ordered pairs satisfying The notation x y indicates that the ordered pair (x, y) satisfies a relation . -

The Diclique Representation and Decomposition of Binary Relations

The Diclique Representation and Decomposition of Binary Relations ROBERT M. HA.RALICK The University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas ABSTRACT. The binary relation is often a useful mathematical structure for representing simple relationships whose essence is a directed connection. To better aid in interpreting or storing a binary relation we suggest a diclique decomposition. A diclique of a binary relation R is defined as an or- dered pair (I, 0) such that I X 0 C R and (I, 0) is maximal. In this paper, an algorithm is described for determining the dicliques of a binary relation; it is proved that the set of such dieliques has a nice algebraic structure. The algebraic structure is used to show how dicliques can be coalesced, the relationship between cliques and dicliques is discussed, and an algorithm for determining cliques from dicliques is described. ~ WORDSAnn lmRASES: graphs, directed graphs, digraphs, cliques, lattices, clustering, dicliques, mo~oids, systems CR CATEGORIES: 3.29, 3.39, 3.63, 5.32 1. Introduction The binary relation is often a useful mathematical structure for representing simple re- lationships whose essence is a directed connection. One important application for the binary relation occurs in the field of general systems theory where a binary relation R can be constructed from a particular discipline theory or constructed empirically from a data set, where the relation R is considered to be the set of all pairs of variables (x, y) where variable x in some sense influences, controls, or dominates variable y. Typically, there are three problems associated with such a binary relation: (1) drawing the binary relations as a digraph, (2) storing the binary relation in the computer, and (3) using the binary relation to get clues concerning which sets of variables form subsystems and for each subsystem determining the input variables and the output variables. -

Lattice Theory

Chapter 1 Lattice theory 1.1 Partial orders 1.1.1 Binary Relations A binary relation R on a set X is a set of pairs of elements of X. That is, R ⊆ X2. We write xRy as a synonym for (x, y) ∈ R and say that R holds at (x, y). We may also view R as a square matrix of 0’s and 1’s, with rows and columns each indexed by elements of X. Then Rxy = 1 just when xRy. The following attributes of a binary relation R in the left column satisfy the corresponding conditions on the right for all x, y, and z. We abbreviate “xRy and yRz” to “xRyRz”. empty ¬(xRy) reflexive xRx irreflexive ¬(xRx) identity xRy ↔ x = y transitive xRyRz → xRz symmetric xRy → yRx antisymmetric xRyRx → x = y clique xRy For any given X, three of these attributes are each satisfied by exactly one binary relation on X, namely empty, identity, and clique, written respectively ∅, 1X , and KX . As sets of pairs these are respectively the empty set, the set of all pairs (x, x), and the set of all pairs (x, y), for x, y ∈ X. As square X × X matrices these are respectively the matrix of all 0’s, the matrix with 1’s on the leading diagonal and 0’s off the diagonal, and the matrix of all 1’s. Each of these attributes holds of R if and only if it holds of its converse R˘, defined by xRy ↔ yRx˘ . This extends to Boolean combinations of these attributes, those formed using “and,” “or,” and “not,” such as “reflexive and either not transitive or antisymmetric”. -

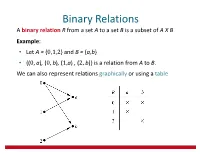

Binary Relations

Binary Relations A binary relation R from a set A to a set B is a subset of A X B Example: • Let A = {0,1,2} and B = {a,b} • {(0, a), (0, b), (1,a) , (2, b)} is a relation from A to B. We can also represent relations graphically or using a table © 2019 McGraw-Hill Education Binary relations on a set A binary relation R on a (single) set A is a subset of A X A Graphical representation: As a directed graph Example: © 2019 McGraw-Hill Education Binary relations on a set A binary relation R on a (single) set A is a subset of A X A Properties of binary relations on a set A: Reflexive Symmetric Transitive Antisymmetric © 2019 McGraw-Hill Education Equivalence Relations A relation on a set A is called an equivalence relation if it is reflexive, symmetric, and transitive. Two elements a, and b that are related by an equivalence relation are called equivalent. The notation a ∼ b is often used to denote that a and b are equivalent elements with respect to a particular equivalence relation. © 2019 McGraw-Hill Education Congruence Modulo m The congruence modulo m relation (for a given positive integer m): a ≡ b (mod m) if and only if m divides (a-b) Example: m = 10 12 ≡ 2 (mod 10) 22 ≡ 2 (mod 10) 1802 ≡ 2 (mod 10) Example: m = 7 Congruence modulo m is an equivalence relation on the integers 12 ≡ 5 (mod 7) 22 ≡ 1 (mod 7) 1802 ≡ 3 (mod 7) © 2019 McGraw-Hill Education Equivalence Classes Let R be an equivalence relation on a set A.