To Start Or Not to Start? an Empirical Examination of the Decision to Start a Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New CSC Computing Resources

New CSC computing resources Atte Sillanpää, Nino Runeberg CSC – IT Center for Science Ltd. Outline CSC at a glance New Kajaani Data Centre Finland’s new supercomputers – Sisu (Cray XC30) – Taito (HP cluster) CSC resources available for researchers CSC presentation 2 CSC’s Services Funet Services Computing Services Universities Application Services Polytechnics Ministries Data Services for Science and Culture Public sector Information Research centers Management Services Companies FUNET FUNET and Data services – Connections to all higher education institutions in Finland and for 37 state research institutes and other organizations – Network Services and Light paths – Network Security – Funet CERT – eduroam – wireless network roaming – Haka-identity Management – Campus Support – The NORDUnet network Data services – Digital Preservation and Data for Research Data for Research (TTA), National Digital Library (KDK) International collaboration via EU projects (EUDAT, APARSEN, ODE, SIM4RDM) – Database and information services Paituli: GIS service Nic.funet.fi – freely distributable files with FTP since 1990 CSC Stream Database administration services – Memory organizations (Finnish university and polytechnics libraries, Finnish National Audiovisual Archive, Finnish National Archives, Finnish National Gallery) 4 Current HPC System Environment Name Louhi Vuori Type Cray XT4/5 HP Cluster DOB 2007 2010 Nodes 1864 304 CPU Cores 10864 3648 Performance ~110 TFlop/s 34 TF Total memory ~11 TB 5 TB Interconnect Cray QDR IB SeaStar Fat tree 3D Torus CSC -

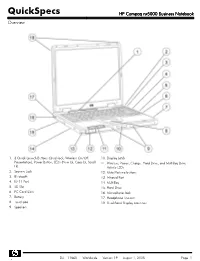

HP Compaq Nx5000 Business Notebook Overview

QuickSpecs HP Compaq nx5000 Business Notebook Overview 1. 3 Quick Launch Buttons (Quicklock, Wireless On/Off, 10. Display Latch Presentation), Power Button, LEDs (Num Lk, Caps Lk, Scroll 11. Wireless, Power, Charge, Hard Drive, and MultiBay Drive Lk) Activity LEDs 2. Security Lock 12. Mute/Volume buttons 3. Bluetooth 13. Infrared Port 4. RJ-11 Port 14. MultiBay 5. SD Slot 15. Hard Drive 6. PC Card Slots 16. Microphone Jack 7. Battery 17. Headphone line-out 8. Touchpad 18. Dual-Band Display Antennas 9. Speakers DA - 11860 Worldwide — Version 19 — August 1, 2005 Page 1 QuickSpecs HP Compaq nx5000 Business Notebook Overview 1. Power Connector 5. VGA 2. Serial 6. IEEE-1394 3. Parallel 7. RJ-45 4. S-Video 8. USB 2.0 (2) At A Glance Microsoft Windows XP Professional, Microsoft Windows XP Home Edition Intel® Pentium® M Processors up to 2.0 GHz Intel Celeron™ M up to 1.4-GHz Intel 855GM chipset with 400-MHz front side bus FreeDOS™ and SUSE® Linux HP Edition 9.1 preinstalled Support for 14.1-inch and 15.0-inch display 266-MHz DDR SDRAM 2 SODIMM slots available – upgradeable to 2048 MB Up to 60-GB 4200 or 5400 rpm, user-removable hard drives. 10/100 Ethernet NIC Touchpad with right/left button Support for MultiBay devices Support for Basic Port Replicator and Advanced Port Replicator Protected by a One- or Three-Year, Worldwide Limited Warranty – certain restrictions and exclusions apply. Consult the HP Customer Support Center for details. What's Special Microsoft Windows XP Professional, Microsoft Windows XP Home Edition Sleek industrial design with weight starting at 5.44 lb (travel weight) and 1.38-inch thin Integrated Intel Extreme Graphics 2 with up to 64 MB of dynamically allocated shared system memory for graphics Up to 9 hours battery life with 8-cell standard Li-Ion battery and Multibay battery. -

Utilizing the Modern Computing Capabilities of the HP Nonstop Server a Business White Paper from Creative System Software, Inc

Utilizing the Modern Computing Capabilities of the HP NonStop Server A business white paper from Creative System Software, Inc. Executive Summary ................................................ 2 The Road To NonStop ............................................. 2 Software Development – Time To Market .............. 4 A Tale Of Two Developers ...................................... 5 Modern Tools And Technologies ............................ 6 System Management ............................................. 7 Security .................................................................. 8 Make Your Data Accessible .................................... 9 The Proof Of The Pudding Is In The Eating ............ 10 Summary .............................................................. 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY During a downturn, it’s hard to see the upside, revenues are down and budgets have fallen along with them. Companies have frozen capital expenditures and the push is on to cut the costs of IT. This means intense pressure to do far more with fewer resources. For years, companies have known that they need to eliminate duplication of effort, lower service costs, increase efficiency, and improve business agility by reducing complexity. Fortunately there are some technologies that can help, the most important of which is the HP Integrity NonStop server platform. The Integrity NonStop is a modern, open and standards based computing platform that just happens to offer the highest reliability and scalability in the industry along with an outstanding total -

Compaq Ipaq H3650 Pocket PC

Compaq iPAQ H3650 QUICKSPECS Pocket PC Overview . AT A GLANCE . Easy expansion and customization . through Compaq Expansion Pack . System . • Thin, lightweight design with . brilliant color screen. • Audio record and playback – . Audio programs from the web, . MP3 music, or voice notations . • . Rechargeable battery that gives . up to 12 hours of battery life . • Protected by Compaq Services, . including a one-year warranty — . Certain restrictions and exclusions . apply. Consult the Compaq . Customer Support Center for . details. In Canada, consult the . Product Information Center at 1- . 800-567-1616 for details. 1. Instant on/off and Light Button 7. Calendar Button . 2. Display 8. Voice Recorder Button . 3. QStart Button 9. Microphone . 4. QMenu 10. Ambient Light Sensor . 5. Speaker and 5-way joystick 11. Alarm/Charge Indicator Light . 6. Contacts Button . 1 DA-10632-01-002 — 06.05.2000 Compaq iPAQ H3650 QUICKSPECS Pocket PC Standard Features . MODELS . Processor . Compaq iPAQ H3650 Pocket . 206 MHz Intel StrongARM SA-1110 32-bit RISC Processor . PC . Memory . 170293-001 – NA Commercial . 32-MB SDRAM, 16-MB Flash Memory . Interfaces . Front Panel Buttons 5 buttons plus five-way joystick; (1 on/off and backlight button and (2-5) . customizable application buttons) . Navigator Button 1 Five-way joystick . Side Panel Recorder Button 1 . Bottom Panel Reset Switch 1 . Stylus Eject Button 1 . Communications Port includes serial port . Infrared Port 1 (115 Kbps) . Speaker 1 . Light Sensor 1 . Microphone 1 . Communications Port 1 (with USB/Serial connectivity) . Stereo Audio Output Jack 1 (standard 3.5 mm) . Cradle Interfaces . Connector 1 . Cable 1 USB or Serial cable connects to PC . -

Sps3000 030602.Qxd (Page 1)

SPS 3000 MOBILE ACCESSORIES Scanning and Wireless Connectivity for the Compaq iPAQ™ Pocket PC The new Symbol SPS 3000 is the first expansion pack that delivers integrated data capture and real-time wireless communi- cation to users of the Compaq iPAQ™ Pocket PC. With the SPS 3000, the Compaq iPAQ instantly becomes a more effective, business process automation tool with augmented capabilities that include bar code scanning and wireless connectivity. Compatible, Versatile and Flexible The SPS 3000 pack attaches easily to the Compaq iPAQ Pocket PC, and the lightweight, ergonomic design provides a secure, comfortable fit in the hand. The coupled device maintains 100% compatibility with Compaq iPAQ recharging and synchronization cradles for maximum convenience and cost-effectiveness. Features Benefits The SPS 3000 is available in three feature configurations: Symbol’s 1-D scan engine Fast, accurate data capture Scanning only; Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN) only; Integrated 802.11b WLAN Enables real-time information Scanning and WLAN. sharing between remote activities Scanning Only: Enables 1-dimensional bar code scanning, and host system which is activated using any of the five programmable Ergonomic, lightweight design Offers increased user comfort and application buttons on the Compaq iPAQ. An optional ‘virtual’ acceptance on-screen button may also be used. Peripheral compatibility Maximum convenience and WLAN Only: Provides 11Mbps Direct Sequence WLAN efficiency ® connectivity through an integrated Spectrum24 802.11b radio Very low power consumption Maintains expected battery life of and antenna. device Scanning and WLAN: Delivers a powerful data management solution with integrated bar code scanning and WLAN the corporate intranet, the Internet or mission critical applications, communication. -

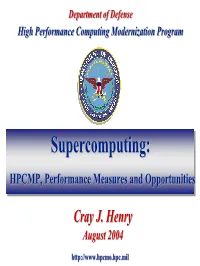

Supercomputing

DepartmentDepartment ofof DefenseDefense HighHigh PerformancePerformance ComputingComputing ModernizationModernization ProgramProgram Supercomputing:Supercomputing: CrayCray Henry,Henry, DirectorDirector HPCMP,HPCMP, PerformancePerformance44 May MayMeasuresMeasures 20042004 andand OpportunitiesOpportunities CrayCray J.J. HenryHenry AugustAugust 20042004 http://http://www.hpcmo.hpc.milwww.hpcmo.hpc.mil 20042004 HPECHPEC ConferenceConference PresentationPresentation OutlineOutline zz WhatWhat’sWhat’’ss NewNew inin thethe HPCMPHPCMP 00NewNew hardwarehardware 00HPCHPC SoftwareSoftware ApplicationApplication InstitutesInstitutes 00CapabilityCapability AllocationsAllocations 00OpenOpen ResearchResearch SystemsSystems 00OnOn-demand-demand ComputingComputing zz PerformancePerformance MeasuresMeasures -- HPCMPHPCMPHPCMP zz PerformancePerformance MeasuresMeasures –– ChallengesChallengesChallenges && OpportunitiesOpportunities HPCMPHPCMP CentersCenters 19931993 20042004 Legend MSRCs ADCs and DDCs TotalTotal HPCMHPCMPP EndEnd-of-Year-of-Year ComputationalComputational CapabilitiesCapabilities 80 MSRCs ADCs 120,000 70 13.1 MSRCs DCs 100,000 60 23,327 80,000 Over 400X Growth 50 s F Us 60,000 40 eak G HAB 12.1 P 21,759 30 59.3 40,000 77,676 5,86 0 20,000 4,393 30,770 20 2.6 21,946 1, 2 76 3,171 26.6 18 9 3 6 0 688 1, 16 8 2,280 8,03212 , 0 14 2.7 18 1 47 10 0 1,944 3,477 10 15.7 0 50 400 1,200 10.6 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 0 199 199 199 199 199 199 199 200 200 200 200 200 FY 01 FY 02 FY 03 FY 04 Year Fiscal Year (TI-XX) HPCMPHPCMP SystemsSystems (MSRCs)(MSRCs)20042004 -

Nonstop Product Offerings and Roadmap

NonStop Product Offerings and Roadmap Iain Liston-Brown (EMEA NED Presales Consulting) 8th May, 2013 © Copyright 2013 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Forward-looking statements This is a rolling (up to three year) Roadmap and is subject to change without notice. This document contains forward looking statements regarding future operations, product development, product capabilities and availability dates. This information is subject to substantial uncertainties and is subject to change at any time without prior notification. Statements contained in this document concerning these matters only reflect Hewlett Packard's predictions and / or expectations as of the date of this document and actual results and future plans of Hewlett-Packard may differ significantly as a result of, among other things, changes in product strategy resulting from technological, internal corporate, market and other changes. This is not a commitment to deliver any material, code or functionality and should not be relied upon in making purchasing decisions. 2 © Copyright 2013 Hewlett-Packard Development Company, L.P. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. HP confidential information This is a rolling (up to three year) Roadmap and is subject to change without notice. This Roadmap contains HP Confidential Information. If you have a valid Confidential Disclosure Agreement with HP, disclosure of the Roadmap is subject to that CDA. If not, it is subject to the following terms: for a period of 3 years after the date of disclosure, you may use the Roadmap solely for the purpose of evaluating purchase decisions from HP and use a reasonable standard of care to prevent disclosures. -

Mr. Capellas Has Served As Our Non-Executive Chairman of the Chairman of the Board Board Since June 2017 and As a Member of Our Board of Directors Since March 2014

Toppan Merrill - Flex LTD Annual Report Combo Book - FYE 3.31.19 ED | 105212 | 09-Jul-19 16:19 | 19-11297-1.bb | Sequence: 20 CHKSUM Content: 43498 Layout: 11362 Graphics: 60748 CLEAN Part III—Proposals to be Considered at the 2019 Annual General Meeting of Shareholders AGM Proposal Nos. 1 and 2: Re-Election of Directors Michael D. Capellas, Mr. Capellas has served as our non-executive Chairman of the Chairman of the Board Board since June 2017 and as a member of our Board of Directors since March 2014. He has served as Principal at Capellas Strategic Principal, Capellas Partners since June 2013. He served as the Chairman of the Board Strategic Partners of VCE Company, LLC (VCE) from January 2011 until Director Since: 2014 November 2012 and as VCE’s Chief Executive Officer from May 2010 to September 2011. VCE is a joint venture between EMC Age: 64 Corporation and Cisco with investments from VMware, Inc. and Intel Board Committee: Corporation. Mr. Capellas was the Chairman and Chief Executive Nominating and Corporate Officer of First Data Corporation from September 2007 to Governance Committee (Chair) March 2010. From October 2006 to July 2007, Mr. Capellas served as a Senior Advisor at Silver Lake Partners. From November 2002 Other Public Company to January 2006, he served as Chief Executive Officer of MCI, Inc. Boards: (MCI), previously WorldCom, Inc. From March 2004 to Cisco Systems, Inc. January 2006, he also served as that company’s President. From November 2002 to March 2004, he was also Chairman of the Board Key Qualifications and of WorldCom, and he continued to serve as a member of the board Expertise: of directors of MCI until January 2006. -

![A. Spirit [Cover] F09 11.25](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8987/a-spirit-cover-f09-11-25-1228987.webp)

A. Spirit [Cover] F09 11.25

THE TEXAS A&M FOUNDATION MAGAZINE | FALL 2009 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Foundation Steers Steady Course In September the Texas A&M Foundation celebrated its 56th birthday and 10th anniversary in the Jon L. Hagler Center. It was a delight to see more than 400 of you—our former students and friends—at our pregame celebration Sept. 5. Much has changed since we moved into our new building in 1999. Many of you recall when the corner of Houston and what used to be “Jersey” Street was the University Police station. A few of you might remember even further back, when this spot was the location of an old county project house built in the late 1930s. There is a certain elegant symbolism in the fact that the campus home to major-gift philanthropy—the Hagler Center—sits on the site of a fundamental act of charity: folks back home helping poor kids go to college. Ten years ago the Foundation employed 72 people and managed assets of $537.9 million. Today we have 95 on our staff and oversee $1.2 billion in assets for Texas A&M. Back then we didn’t have an Internet and fans were just good Ags at Kyle Field, not people following our Facebook page. I’m privileged to say that my position and title have not changed since 1993. Bob Rutledge, my predecessor, directed the Foundation for 12 years before me. I hope you agree that this stable leadership, along with your generous gifts, has contributed to our success. Leadership change at A&M has been much in the news. -

Quickspecs Compaq S710 CRT Monitor

RETIRED: Retired products sold prior to the November 1, 2015 separation of Hewlett-Packard Company into Hewlett Packard Enterprise Company and HP Inc. may have older product names and model numbers that differ from current models. QuickSpecs Compaq S710 CRT Monitor MODELS S710 CRT Monitor (EMEA, CKK, APD and Brazil Model for Opal) (Worldwide model for Carbon color and Multi-media) Opal Color SKUs Carbon Color SKUs 154499-011- Australia 154499-002 – NA 154499-021 - EMEA 154499-012 – Australia 154499-031 - UK 154499-02 - EMEA 154499-201- Equatorial 154499-033 - UK 154499-291 - Japan 154499-B2 - Equatorial 154499-A91 - Dubai Hub 154499-AA - China 154499-B23- South Africa 154499-29 - Japan 154499-B24 – AP 154499-AD - Korea 154499-B2 - South Africa Multi-Media Opal SKUs 154499-005 – NA 154499-B35 - Singapore 154499-025 - EMEA 154499-035 - UK Note: AssetControl monitor. AssetControl features are accessible with Compaq desktops featuring Intelligent Manageability. SPECIFICATIONS Type Color multiple scan with Invar Shadow Mask Picture Tube (diagonal) 17-inch Flat Square Viewable (diagonal) 16.0 inch (40.6 cm) Horizontal Dot Pitch 0.24 mm Trio Dot Pitch 0.28 mm Max Refresh/Preset Graphic Modes 1600 x 1200 1280 x 1024 1024 x 768 Note: All modes are non-interlaced unless N/A N/A/N/A 85 Hz/75 and 85 Hz specified otherwise. 800 x 600 640 x 480 640 x 350 110 Hz/75, 85 Hz 125 Hz/60, 75 125 Hz/N/A and 85 Hz Text Mode 720 x 400 70 Hz Mac Compatible Modes 832 x 624 1152 x 870 Note: Adapter required. -

Modem by 3Com Compaq Global Mini PCI 10/100 LAN + 56K (V.90)

White Paper July 1999 0203-0799-A Compaq Global Mini PCI 56k (V.90) Prepared by Modem by 3Com Portable Marketing Services Compaq Computer Corporation Compaq Global Mini PCI 10/100 Contents Using Modem Commands ..........3 Entering a Command.................3 LAN + 56k (V.90) Modem by 3Com Editing and Executing a Command...............................3 Omitting a Parameter in a Command Line.......................3 Repeating a Command..............3 Modem Commands Understanding Result Codes.....4 Using Online Mode ....................4 Escaping from an Online Session to the Command Abstract: This document includes comprehensive coverage of the Mode ......................................4 following topics: Creating a Command Mode • Shortcut..................................4 AT command set used to control modem functionality at an Creating a Command Mode advanced level Icon ........................................4 AT Command Set ........................6 • S-registers used to control modem functionality at and advanced AT Data Command Set level Summary................................6 Result Code Summary...............7 AT Command Descriptions........9 S Registers.................................24 Setting S Register Default Values ..................................24 Modifying an S Register...........24 Reading an S Register.............24 S-Register Summary ...............25 S-Register Descriptions ...........26 Compaq Global Mini PCI 56k (V.90) Modem by 3Com 2 White Paper Notice The information in this guide is subject to change without notice. COMPAQ COMPUTER CORPORATION SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR TECHNICAL OR EDITORIAL ERRORS OR OMISSIONS CONTAINED HEREIN; NOR FOR INCIDENTAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES RESULTING FROM THE FURNISHING, PERFORMANCE, OR USE OF THIS MATERIAL. This guide contains information protected by copyright. No part of this guide may be photocopied or reproduced in any form without prior written consent from Compaq Computer Corporation. -

Maintenance and Service Guide / Compaq Evo Notebook

b Maintenance and Service Guide Compaq Evo Notebook N1020v Series Compaq Evo Notebook N1000v Series Compaq Presario 1500 Series Mobile PC Document Part Number: 279372-002 November 2002 This guide is a troubleshooting reference used for maintaining and servicing the notebook. It provides comprehensive information on identifying computer features, components, and spare parts, troubleshooting computer problems, and performing computer disassembly procedures. © 2002 Compaq Information Technologies Group, L.P. Compaq, the Compaq logo, Evo, and Presario are trademarks of Compaq Information Technologies Group, L.P. in the U.S. and/or other countries. Microsoft and Windows are trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. Intel, Pentium, Celeron, and SpeedStep are trademarks of the Intel Corporation in the U.S. and/or other countries. All other product names mentioned herein may be trademarks of their respective companies. Compaq shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. The information in this document is provided “as is” without warranty of any kind and is subject to change without notice. The warranties for Compaq products are set forth in the express limited warranty statements accompanying such products. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. Maintenance and Service Guide Second Edition November 2002 First Edition July 2002 Document Part Number: 279372-002 Contents 1 Product Description 1.1 Models . 1–2 1.2 Features . 1–27 1.3 Clearing a Password. 1–29 1.4 Power Management . 1–30 1.5 Computer External Components . 1–31 1.6 Design Overview . 1–41 2 Troubleshooting 2.1 Computer Setup and Diagnostics Utilities .