Dalrev Vol27 Iss1 Pp21 27.Pdf (1.150Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the East London Line

HISTORY OF THE EAST LONDON LINE – FROM BRUNEL’S THAMES TUNNEL TO THE LONDON OVERGROUND by Oliver Green A report of the LURS meeting at All Souls Club House on 11 October 2011 Oliver worked at the London Transport Museum for many years and was one of the team who set up the Covent Garden museum in 1980. He left in 1989 to continue his museum career in Colchester, Poole and Buckinghamshire before returning to LTM in 2001 to work on its recent major refurbishment and redisplay in the role of Head Curator. He retired from this post in 2009 but has been granted an honorary Research Fellowship and continues to assist the museum in various projects. He is currently working with LTM colleagues on a new history of the Underground which will be published by Penguin in October 2012 as part of LU’s 150th anniversary celebrations for the opening of the Met [Bishops Road to Farringdon Street 10 January 1863.] The early 1800s saw various schemes to tunnel under the River Thames, including one begun in 1807 by Richard Trevithick which was abandoned two years later when the workings were flooded. This was started at Rotherhithe, close to the site later chosen by Marc Isambard Brunel for his Thames Tunnel. In 1818, inspired by the boring technique of shipworms he had studied while working at Chatham Dockyard, Brunel patented a revolutionary method of digging through soft ground using a rectangular shield. His giant iron shield was divided into 12 independently moveable protective frames, each large enough for a miner to work in. -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

Commencement1984.Pdf (5.851Mb)

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/commencement1984 ORDER OF PROCESSION MARSHALS Bessni L. Maurice J. an Joseph Katz Arthur Bushel Peter B. Petersen Charles F. Doran A. J. R. RussellAVood Bruce R. Eicher Gilbert B. Schiffman Robert E. Green Henry M. Seidel Richard L. Higcins Mack Walker William H. Huggins Charles R. \Vestgate THE GIL\DUATES * MARSHALS Owen M. Phillips David S. Olton THE DEANS MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY THE TRUSTEES MARSHALS WiLUAM Harrington Dean W. Robinson THE FACULTIES * CHIEF MARSHAL Carl F. Christ THE CHAPLAINS THE HONORARY DEGREE CANDIDATES THE PROVOST OF THE UNIVERSITY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNIVERSITY ORDER OF EVENTS STEVEN MULLER President of the University, presiding PRELUDE Fanfares and Parade Marches Richard Strauss (1864-1949) PROCESSIONALS The audience is requested to stand as the Academic Procession moves into the area and to remain standing after the Invocation Grand Entree, from "Alceste" Where'er You Walk, from "Semele" Fireworks Music Georg Frfdrich Handel (1685-1759) THE PRESIDENT'S PROCESSION Fanfare Walter Piston (1894-1976) March for "Athalie" Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) INVOCATION CHESTER L. WICKWIRE Chaplain The Johns Hopkins University * THE NATIONAL ANTHEiNI GREETINGS GEORGE G. RADCLIFFE Chairman of the Board of Trustees PRESENTATION OF NEW MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF SCHOLARS GUILLERMO ArBONA STEPHEN JoSEPH RyAN, Jr. Charles C. J. Carpenter Asher P. Schick David B. Clark Donald W. Simborg Francis R. Hama Frank Coij: Spencer Joseph E. Johnson, III Newman Lloyd Stephens Peter J. -

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) a Classic Deep

AMERICAN PALE Bianca Road APA 4.6% (Bermondsey) A classic deep amber APA with fruity and refreshing flavours £4.50 Brixton Atlantic APA 5.4% (Brixton) Burst of tropical fruits for a refreshing American pale finish £4.50 INDIAN PALE ALE Mondo Kemosabe IPA 6.4% (Battersea) Dry, malty IPA, a mingle of flavours on the nose classic £4.50 Pressure Drop Mimic 6.2% (Tottenham) A rye IPA, zesty with a subtle spice £4.50 Hackney Push Eject 6.5 (Hackney) Heavily hopped, unfiltered & unfined. Hazy with tropical notes £4.50 SESSION IPA Mondo Little Victories 4.3% (Battersea) A well balanced session IPA, nice body and a hint of sweetness £4.50 LAGER Portobello Pils 4.6% (White City) Full rounded continental flavoured pilsner £3.95 Mondo All Caps 4.9% (Battersea) Corn like sweetness for this American pils £4.50 Brick Peckham Pils 4.8% (Peckham Rye) Czech style pilsner, light & refreshing £4.50 AMBER Gipsy Hill Southpaw 4.2% (Gipsy Hill) Mouthful of malt and hops meet citrus balance £4.50 SOUR Signature Jam Sour 4% (Leyton) A dry hopped raspberry sour, sharp, sweet, topical and zingy £4.50 Weird Beard Sour Slave 4% (Hanwell) Dry hopped kettle sour with a clean citrus acidity (Vg) £4.50 PALE ALE Hackney Kapow! 4.5% (Hackney) Juicy, tropical dry hopped pal. Unfiltered for bigger flavours £4.50 PORTER Bianca Road Vanilla Coffee Porter 4.5% (Bermondsey) Bitter and sweet combine with a hint of vanilla £4.50 BELGIAN & GRISETTE Structure of Matter 4.5% (Ilford) Smooth and quaffable, orangey hops, spicy and malty taste £4.50 Hello, Grisette me you’re looking for? 4.1% (Hanwell) A taste of fresh fruit salad with £4.50 a wheat serenade STOUT £4.50 Brixton Windrush Stout 5% (Brixton) Rich, chocolatey & smooth, with a creamy finish £5.00 Lord Malmölé 7.2% (Battersea) Mondo and Malmo brewery combine for this wonderful stout £4.25 Belleville Southie Stout 5.1% (Wandsworth) Rich and silky with a citrusy-herbal kick. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

WILLIAM SHIPLEY and the ROYAL SOCIETY of ARTS: the History of an Idea

JOURNALOF THE ROYALSOCIETY OF ARTS I ITH MARCHI949 object whichwould be beautifulto look at, suitablefor its purpose,and, at the same time,practical to make. Exhibition An Exhibitionof winningand commendeddesigns is to be held at the Society's House from21 March-2 April,and will be opento thepublic from 10 a.m.-5.3op.m. on Mondays to Fridays,and 10 a.m.-12. 30 p.m. on Saturdays.It is hoped that Fellows will be able to findan opportunityof visiting this Exhibition, but the Board would liketo stressthat the real benefits of the Bursaries are revealedin theprogress made and experiencegained by winningcandidates during their visits abroad, rather than in the entriessubmitted, by which the fullvalue of theseCompetitions can hardlybe judged. As an example of this, the Juryof the Domestic Solid-Fuel- BurningAppliances Section were able to reportthat Mr. R.T.J. Homes,the winning candidate in this Section, who had also been awarded a Bursaryin the 1947 Competition,had made a greatdeal of progressduring the year, and clearlybenefited fromhis visit to Sweden last summer. Copies ofthe full Report, which contains details of the subjects set, the number of entries,the names of the commended candidates and thecomments and composition of the Juries,may be obtainedon applicationto the Secretary. 1949 Competition A furtherannouncement will be made shortlyof the details of theBursaries to be offeredin the 1949 Competition. WILLIAM SHIPLEY AND THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS: The History of an Idea A lecturedelivered on Monday,17th January, 1949 By K. W. Luckhurst,m.a., Secretaryof the Society Founded in 1754." Behindthe prosaic phrase which appears so regularlyon tfye the Journalof Royal Societyof Arts lies a romanticand generallyunsuspected Our story. -

Upper Tideway (PDF)

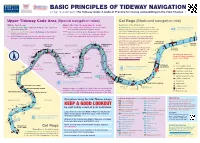

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

Battersea Area Guide

Battersea Area Guide Living in Battersea and Nine Elms Battersea is in the London Borough of Wandsworth and stands on the south bank of the River Thames, spanning from Fairfield in the west to Queenstown in the east. The area is conveniently located just 3 miles from Charing Cross and easily accessible from most parts of Central London. The skyline is dominated by Battersea Power Station and its four distinctive chimneys, visible from both land and water, making it one of London’s most famous landmarks. Battersea’s most famous attractions have been here for more than a century. The legendary Battersea Dogs and Cats Home still finds new families for abandoned pets, and Battersea Park, which opened in 1858, guarantees a wonderful day out. Today Battersea is a relatively affluent neighbourhood with wine bars and many independent and unique shops - Northcote Road once being voted London’s second favourite shopping street. The SW11 Literary Festival showcases the best of Battersea’s literary talents and the famous New Covent Garden Market keeps many of London’s restaurants supplied with fresh fruit, vegetables and flowers. Nine Elms is Europe’s largest regeneration zone and, according the mayor of London, the ‘most important urban renewal programme’ to date. Three and half times larger than the Canary Wharf finance district, the future of Nine Elms, once a rundown industrial district, is exciting with two new underground stations planned for completion by 2020 linking up with the northern line at Vauxhall and providing excellent transport links to the City, Central London and the West End. -

Brunel's Dream

Global Foresights | Global Trends and Hitachi’s Involvement Brunel’s Dream Kenji Kato Industrial Policy Division, Achieving Comfortable Mobility Government and External Relations Group, Hitachi, Ltd. The design of Paddington Station’s glass roof was infl u- Renowned Engineer Isambard enced by the Crystal Palace building erected as the venue for Kingdom Brunel London’s fi rst Great Exhibition held in 1851. Brunel was also involved in the planning for Crystal Palace, serving on the The resigned sigh that passed my lips on arriving at Heathrow building committee of the Great Exhibition, and acclaimed Airport was prompted by the long queues at immigration. the resulting structure of glass and iron. Being the gateway to London, a city known as a melting pot Rather than pursuing effi ciency in isolation, Brunel’s of races, the arrivals processing area was jammed with travel- approach to constructing the Great Western Railway was to ers from all corners of the world; from Europe of course, but make the railway lines as fl at as possible so that passengers also from the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and North and South could enjoy a pleasant journey while taking in Britain’s won- America. What is normally a one-hour wait can stretch to derful rural scenery. He employed a variety of techniques to two or more hours if you are unfortunate enough to catch a overcome the constraints of the terrain, constructing bridges, busy time of overlapping fl ight arrivals. While this only adds cuttings, and tunnels to achieve this purpose. to the weariness of a long journey, the prospect of comfort Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, a famous awaits you on the other side. -

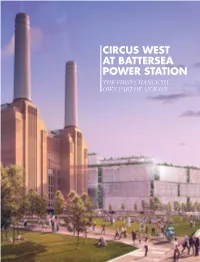

Circus West at Battersea Power Station the First Chance to Own Part of an Icon

CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE FIRST CHANCE TO OWN PART OF AN ICON PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 01 02 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 03 A GLOBAL ICON 04 AN IDEAL LOCATION 06 A PERFECT POSITION 12 A VISIONARY PLACE 14 SPACES IN WHICH PEOPLE WILL FLOURISH 16 AN EXCITING RANGE OF AMENITIES AND ACTIVITIES 18 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 20 RIVER, PARK OR ICON WHAT’S YOUR VIEW? 22 CIRCUS WEST TYPICAL APARTMENT PLANS AND SPECIFICATION 54 THE PLACEMAKERS PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 1 2 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION A GLOBAL ICON IN CENTRAL LONDON Battersea Power Station is one of the landmarks. Shortly after its completion world’s most famous buildings and is and commissioning it was described by at the heart of Central London’s most the Observer newspaper as ‘One of the visionary and eagerly anticipated fi nest sights in London’. new development. The development that is now underway Built in the 1930s, and designed by one at Battersea Power Station will transform of Britain’s best 20th century architects, this great industrial monument into Battersea Power Station is one of the centrepiece of London’s greatest London’s most loved and recognisable destination development. PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 3 An ideal LOCATION LONDON The Power Station was sited very carefully a ten minute walk. Battersea Park and when it was built. It was needed close to Battersea Station are next door, providing the centre, but had to be right on the river. frequent rail access to Victoria Station. It was to be very accessible, but not part of London’s congestion. -

The William Shipley Group

the William Shipley group FOR RSA HISTORY Newsletter 28 June 2011 A message of respect and admiration was sent on behalf of the WSG to HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, KG, KT on the occasion of his retirement as President of the RSA in March 2011. Forthcoming meetings Thursday, 28 July 2011 at 1.00pm. The Eastlakes, the National Gallery and the Victorian Art World. Research Curator and WSG member Dr Susanna Avery-Quash, together with her co-writer Julie Sheldon, will introduce the new Room 1 exhibition on the life and work of the National Gallery’s first director, Sir Charles Lock Eastlake (1793-1865). Admission free. No booking required. Exhibitions Peter Blake: A Museum for Myself. Holburne Museum, Bath, 14 May-4 September 2011 Elected a member of the RSA’s Faculty of RDI’s in 1981, Sir Peter Blake has provided many extraordinary objects from his collections, together with some of his important works, for the opening show of the renewed and transformed Holburne Museum. http://www.holburne.org/peter-blake- a-museum-for-myself/ Royal Society luncheon in honour of H.R.H. Duke of Edinburgh Following the RSA’s celebratory dinner, on 10 March, commemorating over fifty-eight years of Prince Philip’s Presidency the Royal Society held a lunch on 1 June to pay tribute to H.R.H.’s longstanding commitment to science, technology and education. Asa Briggs: A celebration On Thursday 19th May the Institute of Historical Research, in conjunction with the British Association of Victorian Studies, held a one-day colloquium to mark the 90th birthday of one of the country’s most distinguished living historians, Lord Briggs of Lewes. -

Royal Society, 1985

The Public Understanding of Science Report of a Royal Society adhoc Group endorsed by the Council of the Royal Society The Royal Society 6 Carlton House Terrace London SWlY 5AG CONTENTS Page Preface 5 Summary 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Why it matters 9 3. The present position 12 4. Formal education 17 5. The mass media 2 1 6. ' The scientific community 24 7. Public lectures, children's activities, museums and libraries 27 8. Industry 29 9. Conclusions and recommendations 31 Annexes A. List of those submitting evidence B. Visits and seminars C. Selected bibliography PREFACE This report was prepared by an ad hoc group under the chairmanship of Dr W.F. Bodmer, F.R.S.; it has been endorsed by the Council of the Royal Society. It deals with an issue that is important not only, or even mainly, for the scientific community but also for the nation as a whole and for each individual within it. More than ever, people need some understanding of science, whether they are involved in decision-making at a national or local level, in managing industrial companies, in skilled or semi-skilled employment, in voting as private citizens or in making a wide range of personal decisions. In publishing this report the Council hopes that it will highlight this need for an overall awareness of the nature of science and, more particularly, of the way that science and technology pervade modern life, and that it will generate both debate and decisions on how best they can be fostered. The report makes a number of recommendations.