As One Might Expect from the Latin Text of the Kyrie Asini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(1) Western Culture Has Roots in Ancient and ___

5 16. (50) If a 14th-century composer wrote a mass. what would be the names of the movement? TQ: Why? Chapter 3 Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei. The text remains Roman Liturgy and Chant the same for each day throughout the year. 1. (47) Define church calendar. 17. (51) What is the collective title of the eight church Cycle of events, saints for the entire year services different than the Mass? Offices [Hours or Canonical Hours or Divine Offices] 2. TQ: What is the beginning of the church year? Advent (four Sundays before Christmas) 18. Name them in order and their approximate time. (See [Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, 46 days before Easter] Figure 3.3) Matins, before sunrise; Lauds, sunrise; Prime, 6 am; Terce, 9 3. Most important in the Roman church is the ______. am; Sext, noon; Nones, 3 pm; Vespers, sunset; Mass Compline, after Vespers 4. TQ: What does Roman church mean? 19. TQ: What do you suppose the function of an antiphon is? Catholic Church To frame the psalm 5. How often is it performed? 20. What is the proper term for a biblical reading? What is a Daily responsory? Lesson; musical response to a Biblical reading 6. (48) Music in Context. When would a Gloria be omitted? Advent, Lent, [Requiem] 21. What is a canticle? Poetic passage from Bible other than the Psalms 7. Latin is the language of the Church. The Kyrie is _____. Greek 22. How long does it take to cycle through the 150 Psalms in the Offices? 8. When would a Tract be performed? Less than a week Lent 23. -

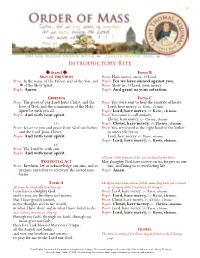

Stand Priest: in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy

1 Stand Form B SIGN OF THE CROSS Priest: Have mercy on us, O Lord. Priest: In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and People: For we have sinned against you. ✠of the Holy Spirit. Priest: Show us, O Lord, your mercy. People: Amen. People: And grant us your salvation. GREETING Form C Priest: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Priest: You were sent to heal the contrite of heart: love of God, and the communion of the Holy Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Spirit be with you all. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: And with your spirit. Priest: You came to call sinners: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Or: People: Christ, have mercy. Or: Christe, eleison. Priest: Grace to you and peace from God our Father Priest: You are seated at the right hand of the Father and the Lord Jesus Christ. to intercede for us: People: And with your spirit. Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. Or: Kyrie, eleison. Or: Priest: The Lord be with you. People: And with your spirit. All forms of the Penitential Act are concluded by the Priest: PENITENTIAL ACT May almighty God have mercy on us, forgive us our Priest: Brethren, let us acknowledge our sins, and so sins, and bring us to everlasting life. prepare ourselves to celebrate the sacred mys- People: Amen. teries. Form A The Kyrie eleison invocations follow, unless they have just occurred All pause for silent reflection then say: in a formula of the Penitential Act (Form C). -

The Penitential Rite & Kyrie

The Mass In Slow Motion Volumes — 7 and 8 The Penitential Rite & The Kyrie The Mass In Slow Motion is a series on the Mass explaining the meaning and history of what we do each Sunday. This series of flyers is an attempt to add insight and understanding to our celebration of the Sacred Liturgy. You are also invited to learn more by attending Sunday School classes for adults which take place in the school cafeteria each Sunday from 9:45 am. to 10:45 am. This series will follow the Mass in order. The Penitential Rite in general—Let us recall that we have just acknowledged and celebrated the presence of Christ among us. First we welcomed him as he walked the aisle of our Church, represented by the Priest Celebrant. The altar, another sign and symbol of Christ was then reverenced. Coming to the chair, a symbol of a share in the teaching and governing authority of Christ, the priest then announced the presence of Christ among us in the liturgical greeting. Now, in the Bible, whenever there was a direct experience of God, there was almost always an experience of unworthiness, and even a falling to the ground! Isaiah lamented his sinfulness and needed to be reassured by the angel (Is 6:5). Ezekiel fell to his face before God (Ez. 2:1). Daniel experienced anguish and terror (Dan 7:15). Job was silenced before God and repented (42:6); John the Apostle fell to his face before the glorified and ascended Jesus (Rev 1:17). Further, the Book of Hebrews says that we must strive for the holiness without which none shall see the Lord (Heb. -

Opening Bell Toll Creed of Prayer on Final Page Psalm 25 Kyrie

Opening Psalm 25 Bell Toll Kyrie Creed of Prayer on final page Preparation Communion Closing Bell Toll Nicene Creed Apostles’ Creed I believe in one God, I believe in God, the Father almighty, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, Creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, All bow at the following words up to: the Virgin Mary. I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Virgin Mary, born of the Father before all ages. suffered under Pontius Pilate, God from God, Light from Light, was crucified, died and was buried; true God from true God, he descended into hell; begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; on the third day he rose again from the dead; through him all things were made. he ascended into heaven, For us men and for our salvation and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; he came down from heaven, All bow at the following words up to: and became man. from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, I believe in the Holy Spirit, and became man. the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints, For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, the forgiveness of sins, he suffered death and was buried, the resurrection of the body, and rose again on the third day and life everlasting. -

Kyrie Eleison. Lord, Have Mercy. Christe Eleison

Third Sunday in Lent March 7, 2021 PRELUDE KYRIE Mozart Mass in C (1756-1791) Kyrie eleison. Lord, Have Mercy. Christe eleison. Christ, have Mercy. Kyrie eleison. Lord, Have Mercy. A PENITENTIAL ORDER Officiantt: Bless the Lord who forgives all our sins. People: His mercy endures for ever. Officiant: Jesus said, “The first commandment is this: Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is the only Lord. Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength. The second is this: Love your neighbor as yourself. There is no other commandment greater than these.” Let us confess our sins against God and our neighbor. All: Most merciful God, we confess that we have sinned against you in thought, word, and deed, by what we have done, and by what we have left undone. We have not loved you with our whole heart; we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves. We are truly sorry and we humbly repent. For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ, have mercy on us and forgive us; that we may delight in your will, and walk in your ways, to the glory of your Name. Amen. Officiant: Almighty God have mercy on you, forgive you all your sins through our Lord Jesus Christ, strengthen you in all goodness, and by the power of the Holy Spirit keep you in eternal life. Amen. TRISAGION Hymnal S-100 COLLECT OF THE DAY Almighty God, you know that we have no power in ourselves to help ourselves: Keep us both outwardly in our bodies and inwardly in our souls, that we may be defended from all adversities which may happen to the body, and from all evil thoughts which may assault and hurt the soul; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Penitential Act: Kyrie Eleison ( “Lord Have Mercy” )

PENITENTIAL ACT: KYRIE ELEISON ( “LORD HAVE MERCY” ) When we ask God for forgiveness, we are asking him for mercy. At this point in the Mass, we plea for God’s mercy 3 times, echoing the priest who is leading us. Asking 3 times demonstrates sorrow for our sins and symbolizes that we are praying to God: as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Repetition is common in the psalms and in prayers of the Mass. It helps to stir the human heart, mind, and soul to prayer. As children often do, we too ask repeatedly for what we desire most: God’s mercy and love. We pray: Lord, have Mercy; Christ have Mercy; Lord have Mercy. As you may recall, much of the New Testament texts were written in Greek, and many of the early Christian liturgies were also initially in Greek. Even though Latin became the language of the Roman Catholic Church circa 500 CE, this prayer was retained in Greek, “ Kyrie eleison ” throughout the universal Church; Christians have said this same prayer for over 1500 years! During the Penitential Act (at the beginning of the Mass), depending on the prescribed form the priest utilizes, we participate in a dialogue with the priest before God, asking for the His Mercy: Priest: Lord, have mercy. Priest: Kyrie eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. People: Kyrie eleison. Priest: Christ, have mercy. Priest: Christe eleison. People: Christ, have mercy. People: Christe eleison. Priest: Lord, have mercy. Priest: Kyrie eleison. People: Lord, have mercy. People: Kyrie eleison. The Lord, Our God loves us unconditionally. All He wants is for us to be in a covenantal relationship of dependence, friendship and love with Him. -

Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 As a Stylistic Guide

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2008 Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide Jonathan Candler Kilgore University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Kilgore, Jonathan Candler, "Four Twentieth-Century Mass Ordinary Settings Surveyed Using the Dictates of the Motu Proprio of 1903 as a Stylistic Guide" (2008). Dissertations. 1129. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC GUIDE by Jonathan Candler Kilgore A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts August 2008 COPYRIGHT BY JONATHAN CANDLER KILGORE 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi FOUR TWENTIETH-CENTURY MASS ORDINARY SETTINGS SURVEYED USING THE DICTATES OF THE MOTU PROPRIO OF 1903 AS A STYLISTIC -

Kyrie Eleison

MG006A $1.75 Kyrie Eleison Traditional Latin Liturgy Anthem TTBB choir, Solo, unaccompanied www.mlagmusic.com MG006A Kyrie Eleison TTBB choir, Solo, unaccompanied (Available for SATB choir with solo) My first setting of the spiritual, “Lord, have mercy,” was a simple song using solo and choral accompaniment. After talking with a mentor about how I could do more with spirituals, the revelation came to combine the spiritual with the traditional text “Kyrie eleison” because of the translation. After a few edits, mostly added rhythmic interest in the final key, the song now exists in its final edition. Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy, Save me now. Save poor sinner, Save me now. Christe eleison. Christ, have mercy. Save me, Jesus… Lord, I’m troubled… Kyrie eleison. Lord, have mercy. Lord, I’m sinking… Lord, have mercy… Additional Titles: I Am Thine (Draw Me Nearer) TTBB MG012B My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord TTBB, Ten. Solo MG002A The Savior’s Birth TTBB MG008B Sing Out, My Soul TTB, piano MG031D A Virginia native, Marques L. A. Garrett is an Assistant Professor of Music in Choral Activities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in the Glenn Korff School of Music. He earned his PhD in Music Education (Choral Conducting) at Florida State University. An active conductor, he has served as a guest conductor or clinician with several high school, church, community, and collegiate choirs throughout the country. Dr. Garrett is an avid composer of choral and solo-vocal music whose compositions have been performed to acclaim by high school all-state, collegiate, and professional choirs including Seraphic Fire and the Oakwood University Aeolians. -

The Deacon at Mass

Diocese of Superior The Deacon at Mass Based on the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (2011) and the Ceremonial of Bishops (1989) September 16, 2014 2 Contents Introduction…………………………………………………….……………………....…….…….. 5 General Principles Reflection on the Ministry of the Deacon………………………………..…….. 6 Assisting at Mass Vesture ……………………………………………………………………………………...……. 7 Preparation for Mass The Ministry of the Deacon in the Celebration of the Mass………………….………….…….. 8 Introductory Rites Entrance Procession -The Deacon’s position in the procession/the Book of Gospels -Number of Assisting Deacons -Order of the opening procession including the Book of Gospels…….. 9 -If the Book of Gospels is excluded from the procession -Assistance with miter/crozier including the possibility of vimps -Bowing toward the altar and kissing the altar…….……………………… 10 -Assistance with miter/crozier without vimps, bowing toward/kissing altar Incensation of the altar and cross……………………………………………….…….. 11 Penitential Act Sprinkling Rite Liturgy of the Word……………………………………………………………………….…….. 12 -Proclamation of the readings Gospel Reading………………………………………………………………….………….….. 12 -Assistance with putting incense in the thurible -Asking for the Priest’s blessing -Assistance with incense boat, asking Bishop’s blessing—standing -Assistance with incense boat, asking Bishop’s blessing—kneeling -Retrieval of the Book of Gospels………………….…………………….….….. 13 -Announcing the Gospel reading -Incensation of the Book of Gospels 3 (Gospel Reading, cont’d.) -After the proclamation………………………………………………..……………….…….. 13 -Veneration of the Book of Gospels and blessing with it -The Deacon as homilist……………………………………………..……….…….. 14 General Intercessions The Liturgy of the Eucharist……………………………………….……………….…….. 15 Receiving the Gifts and Preparing the Altar -Placement of the corporal and vessels -Receiving the gifts -Preparation of the altar -Preparation of the altar with two Deacons -Incensation of the altar, gifts, presiding Priest, other clerics and assembly……………………………………………..……..…. -

PREPARING to HEAR GOD's WORD KYRIE ELEISON, No. 551 Lord

PREPARING TO HEAR GOD’S WORD KYRIE ELEISON, No. 551 Lord, Have Mercy LAND OF REST I believe in the Holy Ghost; the holy catholic church; the CHIMES (The congregation is asked to pray for the blessing of God upon this service.) Congregation and Choir communion of saints; the forgiveness of sins; the resurrection of the God of power, may the boldness of your Spirit transform us, the gentleness of your body; and the life everlasting. Amen. Spirit lead us, and the gifts of your Spirit be our goal and our strength. Amen. PRAYER PRELUDE Source and Sovereign, Rock and Cloud Gerald Near BAPTISM INTROIT We Saw His Glory Erhard Mauersberger WELCOME The Sanctuary Choir RESPONSE, No. 486 Child of Blessing, Child of Promise We saw his glory, Sun of Righteousness, arise, KINGDOM The glory of the only-begotten Son Triumph o’er the shades of night. Congregation and Choir Of the Father, full of grace and truth. Dayspring from on high, be near, Christ, whose glory fills the skies, Daystar, in my heart appear. Children may exit at this time. Parents of children ages 3 years and younger Thou, the true, the only Light, may take their children to the CE building for Extended Session, Room CE 105. ASSURANCE OF PARDON Children in K4 through 1st grade will be escorted to the Worship Center on †CALL TO WORSHIP the third floor of this building, Room 322. †ACT OF PRAISE Gloria Patri MEINEKE On the mountaintop, with the witness of Moses and Elijah, God PRAYER FOR ILLUMINATION transfigured the life of Jesus Christ, Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost: FIRST SCRIPTURE READING 2 Kings 2:1-12 In this place, through the witness of friends and neighbors, old and As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, Pew Bible, page 317; large print, page 412 new, God transfigures us. -

Traditional Latin Mass (TLM), Otherwise Known As the Extraordinary Form, Can Seem Confusing, Uncomfortable, and Even Off-Putting to Some

For many who have grown up in the years following the liturgical changes that followed the Second Vatican Council, the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM), otherwise known as the Extraordinary Form, can seem confusing, uncomfortable, and even off-putting to some. What I hope to do in a series of short columns in the bulletin is to explain the mass, step by step, so that if nothing else, our knowledge of the other half of the Roman Rite of which we are all a part, will increase. Also, it must be stated clearly that I, in no way, place the Extraordinary Form above the Ordinary or vice versa. Both forms of the Roman Rite are valid, beautiful celebrations of the liturgy and as such deserve the support and understanding of all who practice the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. Before I begin with the actual parts of the mass, there are a few overarching details to cover. The reason the priest faces the same direction as the people when offering the mass is because he is offering the sacrifice on behalf of the congregation. He, as the shepherd, standing in persona Christi (in the person of Christ) leads the congregation towards God and towards heaven. Also, it’s important to note that a vast majority of what is said by the priest is directed towards God, not towards us. When the priest does address us, he turns around to face us. Another thing to point out is that the responses are always done by the server. If there is no server, the priest will say the responses himself.