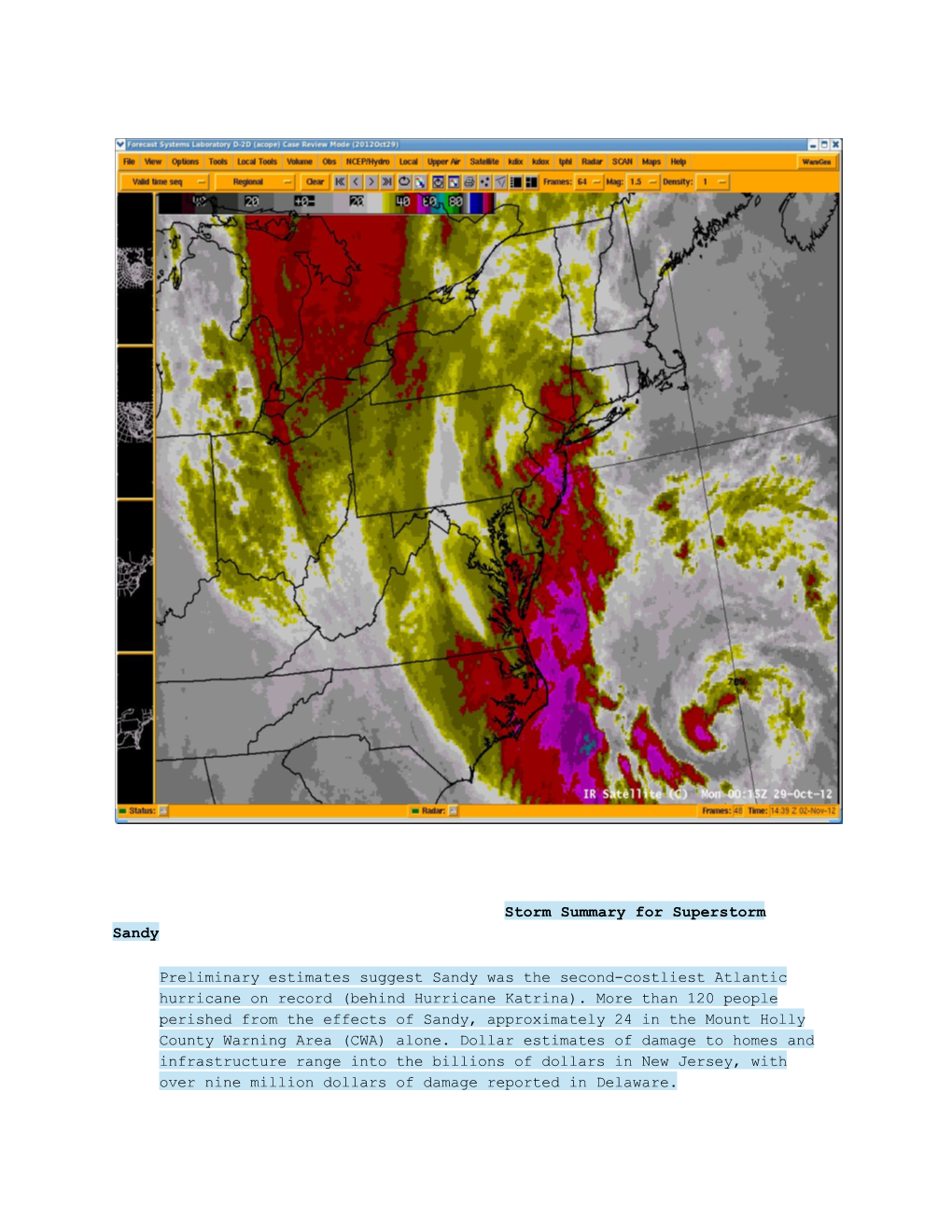

Storm Summary for Superstorm Sandy Preliminary Estimates Suggest Sandy Was the Secondcostliest Atlantic Hurric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeowners Handbook to Prepare for Natural Disasters

HOMEOWNERS HANDBOOK HANDBOOK HOMEOWNERS DELAWARE HOMEOWNERS TO PREPARE FOR FOR TO PREPARE HANDBOOK TO PREPARE FOR NATURAL HAZARDSNATURAL NATURAL HAZARDS TORNADOES COASTAL STORMS SECOND EDITION SECOND Delaware Sea Grant Delaware FLOODS 50% FPO 15-0319-579-5k ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This handbook was developed as a cooperative project among the Delaware Emergency Management Agency (DEMA), the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) and the Delaware Sea Grant College Program (DESG). A key priority of this project partnership is to increase the resiliency of coastal communities to natural hazards. One major component of strong communities is enhancing individual resilience and recognizing that adjustments to day-to- day living are necessary. This book is designed to promote individual resilience, thereby creating a fortified community. The second edition of the handbook would not have been possible without the support of the following individuals who lent their valuable input and review: Mike Powell, Jennifer Pongratz, Ashley Norton, David Warga, Jesse Hayden (DNREC); Damaris Slawik (DEMA); Darrin Gordon, Austin Calaman (Lewes Board of Public Works); John Apple (Town of Bethany Beach Code Enforcement); Henry Baynum, Robin Davis (City of Lewes Building Department); John Callahan, Tina Callahan, Kevin Brinson (University of Delaware); David Christopher (Delaware Sea Grant); Kevin McLaughlin (KMD Design Inc.); Mark Jolly-Van Bodegraven, Pam Donnelly and Tammy Beeson (DESG Environmental Public Education Office). Original content from the first edition of the handbook was drafted with assistance from: Mike Powell, Greg Williams, Kim McKenna, Jennifer Wheatley, Tony Pratt, Jennifer de Mooy and Morgan Ellis (DNREC); Ed Strouse, Dave Carlson, and Don Knox (DEMA); Joe Thomas (Sussex County Emergency Operations Center); Colin Faulkner (Kent County Department of Public Safety); Dave Carpenter, Jr. -

Historic Greensburg Supercell of 4 May 2007 Anatomy of a Severe Local ‘Superstorm’

Historic Greensburg Supercell of 4 May 2007 Anatomy of a Severe Local ‘Superstorm’ Mike Umscheid National Weather Service Forecast Office – Dodge City, KS In collaboration with Leslie R. Lemon University of Oklahoma/CIMMS, NOAA/NWS Warning Decision Training Branch, Norman, OK DuPage County, IL Advanced Severe Weather Seminar March 5-6, 2010 1 © Martin Kucera A Thunderstorm Spectrum Single Cell Multi-cell Multi-cell Supercell (cluster) (line) Short-lived, Longer-lived (2-4hrs), non-tornadic supercells one or two tornadic cycles Courtesy NWS Norman Severe Local “Superstorm” 6+ hrs, 2-3 significant tornadoes (or one ultra long-lived sig tor), Many other smaller ones. Widespread destruction. 9 April 1947 Woodward, OK 2 Woodward – Udall – Greensburg Udall Woodward 10:35 pm 8:42 pm ~ ¾ to 1 mile wide 82 fatalities 1.8 miles wide 107 fatalities Photos courtesy NWS ICT, NW OK Genealogical Society, Mike Theiss Times CST 11 fatalities 1.7 miles wide 8:50 pm Greensburg 3 Integrated Warning System 4 A little preview… EF5 EF3 (+) 0237 0331 EF3 (+) EF3 0347 0437 1 supercell thunderstorm – 20 tornadoes, 4 massive tornadoes spanning 5 3 hours w/ no break, farm community obliterated, very well-documented by chasers “The Big 4” Rating: EF3 (strong) Duration: 65 min. Length: 23.5 mi Mean Width: 1.5 mi St. John Max Width: 2.2 mi Macksville Damage Area: 35.4 mi2 (A5) Rating: EF3 Damage $$: 1.5 M Duration: 24 min. Length: 17.4 mi Mean Width: 0.6 mi Max Width: 0.9 mi Trousdale Damage Area: 9.7 mi2 (A4) Hopewell Fatalities: 1 Rating: EF5 Duration: 65 min. -

2014 Annual Meeting Program Agenda (Preliminary Updated 8 October 2014)

2014 Annual Meeting Program Agenda (Preliminary updated 8 October 2014) National Weather Association 39th Annual Meeting Sheraton Hotel, Salt Lake City, UT October 18-23, 2014 Theme: "Building a 21st Century Weather Enterprise: Facilitating Research to Operations – Optimizing Communication and Response." See the main annual meeting page http://www.nwas.org/meetings/nwa2014/ for information on the meeting hotel, exhibits, sponsorships, attendee registration requirements, social media connections and more. Authors/Presenters, please inform the Annual Meeting Program Committee at [email protected] of any corrections or changes required in the listing of your presentations or abstracts as soon as possible. Instructions for uploading your presentation PowerPoint slides, extended abstracts and posters to the NWA website to be used at the meeting and eventually linked from the final agenda are shown on the "Presentation Instructions and Tips" website page. See "Upload Instructions" then send your file(s) on the Presentation and Extended Abstract Upload website page. All activities will be held in the Sheraton Salt Lake City Hotel unless otherwise noted. All attendees please check in at the NWA Registration and Information Desk as soon as possible upon arriving at the Sheraton Hotel to obtain nametags, the latest program and scheduling information and to register if not preregistered. Please note that this is a preliminary agenda and that changes will occur to the program prior to the meeting. Please check back regularly for any modifications that may impact presentation title, time, room, etc. 1 Saturday – 18 October 10:00 AM Aviation Weather Safety Seminar: Aviation Weather in the Intermountain West The NWA Aviation Meteorology Committee invites all to attend this free valuable seminar (10 AM -1PM) specifically designed for pilots who fly in the Intermountain West. -

Ref. Accweather Weather History)

NOVEMBER WEATHER HISTORY FOR THE 1ST - 30TH AccuWeather Site Address- http://forums.accuweather.com/index.php?showtopic=7074 West Henrico Co. - Glen Allen VA. Site Address- (Ref. AccWeather Weather History) -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- AccuWeather.com Forums _ Your Weather Stories / Historical Storms _ Today in Weather History Posted by: BriSr Nov 1 2008, 02:21 PM November 1 MN History 1991 Classes were canceled across the state due to the Halloween Blizzard. Three foot drifts across I-94 from the Twin Cities to St. Cloud. 2000 A brief tornado touched down 2 miles east and southeast of Prinsburg in Kandiyohi county. U.S. History # 1861 - A hurricane near Cape Hatteras, NC, battered a Union fleet of ships attacking Carolina ports, and produced high tides and high winds in New York State and New England. (David Ludlum) # 1966 - Santa Anna winds fanned fires, and brought record November heat to parts of coastal California. November records included 86 degrees at San Francisco, 97 degrees at San Diego, and 101 degrees at the International airport in Los Angeles. Fires claimed the lives of at least sixteen firefighters. (The Weather Channel) # 1968 - A tornado touched down west of Winslow, AZ, but did little damage in an uninhabited area. (The Weather Channel) # 1987 - Early morning thunderstorms in central Arizona produced hail an inch in diameter at Williams and Gila Bend, and drenched Payson with 1.86 inches of rain. Hannagan Meadows AZ, meanwhile, was blanketed with three inches of snow. Unseasonably warm weather prevailed across the Ohio Valley. Afternoon highs of 76 degrees at Beckley WV, 77 degrees at Bluefield WV, and 83 degrees at Lexington KY were records for the month of November. -

The 1993 Superstorm: 15-Year Retrospective

THE 1993 SUPERSTORM: 15-YEAR RETROSPECTIVE RMS Special Report INTRODUCTION From March 12–14, 1993, a powerful extra-tropical storm descended upon the eastern half of the United States, causing widespread damage from the Gulf Coast to Maine. Spawning tornadoes in Florida and causing record snowfalls across the Appalachian Mountains and Mid-Atlantic states, the storm produced hurricane-force winds and extremely low temperatures throughout the region. Due to the intensity and size of the storm, as well as its far-reaching impacts, it is widely acknowledged in the United States as the ―1993 Superstorm‖ or ―Storm of the Century.‖ During the storm’s formation, the National Weather Service (NWS) issued storm and blizzard warnings two days in advance, allowing the 100 million individuals who were potentially in the storm’s path to prepare. This was the first time the NWS had ever forecast a storm of this magnitude. Yet in spite of the forecasting efforts, about 100 deaths were directly attributed to the storm (NWS, 1994). The storm also caused considerable damage and disruption across the impacted region, leading to the closure of every major airport in the eastern U.S. at one time or another during its duration. Heavy snowfall caused roofs to collapse in Georgia, and the storm left many individuals in the Appalachian Mountains stranded without power. Many others in urban centers were subject to record low temperatures, including -11°F (-24°C) in Syracuse, New York. Overall, economic losses due to wind, ice, snow, freezing temperatures, and tornado damage totaled between $5-6 billion at the time of the event (Lott et al., 2007) with insured losses of close to $2 billion. -

Assimilation of Pseudo-GLM Data Using the Ensemble Kalman Filter

SEPTEMBER 2016 A L L E N E T A L . 3465 Assimilation of Pseudo-GLM Data Using the Ensemble Kalman Filter BLAKE J. ALLEN Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, University of Oklahoma, and NOAA/OAR/National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma EDWARD R. MANSELL NOAA/OAR/National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma DAVID C. DOWELL NOAA/OAR/Earth System Research Laboratory, Boulder, Colorado WIEBKE DEIERLING National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado (Manuscript received 30 March 2016, in final form 13 June 2016) ABSTRACT Total lightning observations that will be available from the GOES-R Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) have the potential to be useful in the initialization of convection-resolving numerical weather models, particularly in areas where other types of convective-scale observations are sparse or nonexistent. This study used the ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF) to assimilate real-data pseudo-GLM flash extent density (FED) observations at convection-resolving scale for a nonsevere multicell storm case (6 June 2000) and a tornadic supercell case (8 May 2003). For each case, pseudo-GLM FED observations were generated from ground-based lightning mapping array data with a spacing approximately equal to the nadir pixel width of the GLM, and tests were done to examine different FED observation operators and the utility of temporally averaging observations to smooth rapid variations in flash rates. The best results were obtained when assimilating 1-min temporal resolution data using any of three ob- servation operators that utilized graupel mass or graupel volume. Each of these three observation operators performed well for both the weak, disorganized convection of the multicell case and the much more intense convection of the supercell case. -

NWS Unified Surface Analysis Manual

Unified Surface Analysis Manual Weather Prediction Center Ocean Prediction Center National Hurricane Center Honolulu Forecast Office November 21, 2013 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers…………….3 Chapter 2: Datasets available for creation of the Unified Analysis………...…..5 Chapter 3: The Unified Surface Analysis and related features.……….……….19 Chapter 4: Creation/Merging of the Unified Surface Analysis………….……..24 Chapter 5: Bibliography………………………………………………….…….30 Appendix A: Unified Graphics Legend showing Ocean Center symbols.….…33 2 Chapter 1: Surface Analysis – Its History at the Analysis Centers 1. INTRODUCTION Since 1942, surface analyses produced by several different offices within the U.S. Weather Bureau (USWB) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA’s) National Weather Service (NWS) were generally based on the Norwegian Cyclone Model (Bjerknes 1919) over land, and in recent decades, the Shapiro-Keyser Model over the mid-latitudes of the ocean. The graphic below shows a typical evolution according to both models of cyclone development. Conceptual models of cyclone evolution showing lower-tropospheric (e.g., 850-hPa) geopotential height and fronts (top), and lower-tropospheric potential temperature (bottom). (a) Norwegian cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) and (III) narrowing warm sector, (IV) occlusion; (b) Shapiro–Keyser cyclone model: (I) incipient frontal cyclone, (II) frontal fracture, (III) frontal T-bone and bent-back front, (IV) frontal T-bone and warm seclusion. Panel (b) is adapted from Shapiro and Keyser (1990) , their FIG. 10.27 ) to enhance the zonal elongation of the cyclone and fronts and to reflect the continued existence of the frontal T-bone in stage IV. -

Hurricane & Tropical Storm

5.8 HURRICANE & TROPICAL STORM SECTION 5.8 HURRICANE AND TROPICAL STORM 5.8.1 HAZARD DESCRIPTION A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (NOAA, 2013). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. The average wind speeds for tropical storms and hurricanes are listed below: . A tropical depression has a maximum sustained wind speeds of 38 miles per hour (mph) or less . A tropical storm has maximum sustained wind speeds of 39 to 73 mph . A hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or higher. In the western North Pacific, hurricanes are called typhoons; similar storms in the Indian Ocean and South Pacific Ocean are called cyclones. A major hurricane has maximum sustained wind speeds of 111 mph or higher (NOAA, 2013). Over a two-year period, the United States coastline is struck by an average of three hurricanes, one of which is classified as a major hurricane. Hurricanes, tropical storms, and tropical depressions may pose a threat to life and property. These storms bring heavy rain, storm surge and flooding (NOAA, 2013). The cooler waters off the coast of New Jersey can serve to diminish the energy of storms that have traveled up the eastern seaboard. -

The Impact of Superstorm Sandy on New Jersey Towns and Households

THE IMPACT OF SUPERSTORM SANDY ON NEW JERSEY TOWNS AND HOUSEHOLDS Stephanie Hoopes Halpin, PhD School of Public Affairs and Administration, Rutgers-Newark http://spaa.newark.rutgers.edu THE IMPACT OF SUPERSTORM SANDY ON NEW JERSEY TOWNS AND HOUSEHOLDS SUPPORT We are grateful to the following organizations for funding this report: Fund for New Jersey United Way of Northern New Jersey ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The New Jersey League of Municipalities for help with the Survey; Margaret Riccardelli and Shugo Shinohara for research assistance; and Quintus Jett, Diane Wentworth, and Gregg G. Van Ryzin for their insights. CONTACT Stephanie Hoopes Halpin School of Public Affairs and Administration, Rutgers-Newark [email protected]; 973-353-1940 http://spaa.newark.rutgers.edu 2 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 7 I. COMMUNITY HARDSHIP FOLLOWING SUPERSTORM SANDY 12 II. HOUSEHOLD HARDSHIP FOLLOWING SUPERSTORM SANDY 23 III. ALICE CHALLENGES AND CONSEQUENCES 30 IV. MUNICIPAL RESPONSE 37 V. HOW WELL DID RESOURCES MEET NEEDS? 47 VI. CONCLUSION: RECOMMENDATIONS TO BETTER PREPARE FOR THE NEXT DISASTER 62 APPENDIX A: SANDY COMMUNITY HARDSHIP INDEX 67 APPENDIX B: SANDY HOUSEHOLD HARDSHIP INDEX 73 APPENDIX C: SANDY MUNICIPAL SURVEY – METHODOLOGY 75 APPENDIX D: MUNICIPAL INDEX SCORES 82 SOURCES 106 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Horrific stories of storm damage and enormous repair and replacement estimates drew national attention to the impact of Superstorm Sandy on New Jersey. Despite large relief efforts and numerous reports, important questions still remain: Which areas of New Jersey and which groups in our communities were most impacted? Where is there still unmet need? Where do vulnerabilities remain? To address these questions before the next inevitable disaster, we need to understand the hardship incurred by the residential, business and municipal sectors in each town and county in the state, the losses due to physical damage as well as lost income, where they occurred, who was impacted, and what resources have been allocated. -

Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

FLORIDA HURRICANES AND TROPICAL STORMS 1871-1995: An Historical Survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams '+wcCopy~~ I~BN 0-912747-08-0 Florida SeaGrant College is supported by award of the Office of Sea Grant, NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce,grant number NA 36RG-0070, under provisions of the NationalSea Grant College and Programs Act of 1966. This information is published by the Sea Grant Extension Program which functionsas a coinponentof the Florida Cooperative Extension Service, John T. Woeste, Dean, in conducting Cooperative Extensionwork in Agriculture, Home Economics, and Marine Sciences,State of Florida, U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, U.S. Departmentof Commerce, and Boards of County Commissioners, cooperating.Printed and distributed in furtherance af the Actsof Congressof May 8 andJune 14, 1914.The Florida Sea Grant Collegeis an Equal Opportunity-AffirmativeAction employer authorizedto provide research, educational information and other servicesonly to individuals and institutions that function without regardto race,color, sex, age,handicap or nationalorigin. Coverphoto: Hank Brandli & Rob Downey LOANCOPY ONLY Florida Hurricanes and Tropical Storms 1871-1995: An Historical survey Fred Doehring, Iver W. Duedall, and John M. Williams Division of Marine and Environmental Systems, Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, FL 32901 Technical Paper - 71 June 1994 $5.00 Copies may be obtained from: Florida Sea Grant College Program University of Florida Building 803 P.O. Box 110409 Gainesville, FL 32611-0409 904-392-2801 II Our friend andcolleague, Fred Doehringpictured below, died on January 5, 1993, before this manuscript was completed. Until his death, Fred had spent the last 18 months painstakingly researchingdata for this book. -

![Severe Storms [Article MS-366 for the Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2346/severe-storms-article-ms-366-for-the-encyclopedia-of-atmospheric-sciences-762346.webp)

Severe Storms [Article MS-366 for the Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences]

Severe Storms [article MS-366 for the Encyclopedia of Atmospheric Sciences] Charles A. Doswell III, NOAA/National Severe Storms Laboratory, 1313 Halley Circle, Norman, Oklahoma 73069, U.S.A. Introduction The word “storm” implies a disturbance of some sort in the weather, but many different types of weather can result in an event called a “storm.” Thus, it is possible to have windstorms, dust storms (which also are windstorms), hailstorms, thunderstorms, winter storms, tropical storms, and so on. Generally speaking, events called “storms” are associated with cyclones; undisturbed weather is usually found with anticyclones. Similarly, the meaning of severity needs to be considered. The intensity of the event in question is going to be the basis for deciding on the severity of that particular storm. However, if storm intensity is to be our basis for categorizing a storm as severe, then we have to decide what measure we are going to use for intensity. This also implies an arbitrary threshold for deciding the issue of severity. That is, weather events of a given type are going to the called severe when some measure of that event’s intensity meets or exceeds a threshold which is usually more or less arbitrary. A hailstorm might be severe when the hailstone diameters reach 2 cm or larger, a winter snowstorm might be called severe when the snowfall rate equals or exceeds 5 cm per hour. On the other hand, some storms of any intensity might be considered severe. A tornado is a “storm” embedded within a thunderstorm; any tornado of any intensity is considered a severe storm. -

P1.28 a Digital Archive of Significant Florida Weather Events to Improve the Public’S Response to Future Warnings

P1.28 A Digital Archive of Significant Florida Weather Events to Improve the Public’s Response to Future Warnings Charles H. Paxton1,2, Jennifer M. Collins2, Kortnie J. Pugh1,2,3, and Jennifer L. Colson1 1. National Weather Service, Tampa Bay Florida 2. University of South Florida, Tampa, FL 3. National Marine Fisheries Service, St. Petersburg, FL I. Introduction other artifacts. These resources are of immense The past is our guide, our manual, it helps value not only to NOAA but also the American illuminate actions for the future. Through a NOAA people their true owners. Two frail leather-bound Preserve America Initiative grant obtained in U.S. Weather Bureau means books dating back to collaboration between the NWS (Tampa Bay 1890 needed rebinding. The office also has a region) and the University of South Florida (USF) wealth of other record books, older original two students were hired by NMFS Regional office weather maps depicting major events, news to work at the Tampa Bay Area NWS to document articles, and photos of major past events. historic weather events (Fig 1) and preserve weather relics. In an effort to save items of historical content, President Bush through his Preserve America executive order (E.O. 13287) called on NOAA and other federal agencies to inventory, preserve, and showcase federally- managed historic, cultural, or "heritage" resources and foster tourism in partnership with local communities. Fig. 2. Scanned weather photos. Many old weather artifacts from the past have been photographed and existing photographs of past weather events were scanned too (Fig. 2). When in electronic form, the pages of the books make accessible viewing on the Internet.