Dementia with Aphasia and Mirror Phenomenon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

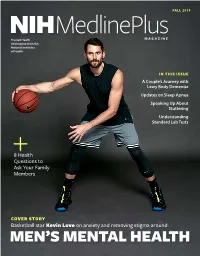

Mlpmfall19.Pdf

FALL 2019 MedlinePlus NIH MAGAZINE Trusted Health Information from the National Institutes of Health IN THIS ISSUE A Couple’s Journey with Lewy Body Dementia Updates on Sleep Apnea Speaking Up About Stuttering Understanding Standard Lab Tests 8 Health Questions to Ask Your Family Members COVER STORY Basketball star Kevin Love on anxiety and removing stigma around MEN’S MENTAL HEALTH In this issue id you know that more than 31% of U.S. adults experience an anxiety disorder at some point Din their lives, according to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)? For our fall issue cover feature, Cleveland Cavaliers basketball player Kevin Love opens up about his own struggles with anxiety and his path to managing the condition. He talks about the special challenges facing men with mental health conditions and explains what he’s doing to combat that stigma as an athlete and advocate. We also spoke with the National Basketball Players Association’s Mental William Parham, Ph.D. (center) is the first-ever director of the National Basketball Players Association’s Mental Health Program. Also pictured Health Program Director William Parham, are Antonio Davis, Keyon Dooling, Michele Roberts, Garrett Temple, Ph.D., about their new program to help and Chris Paul. players stay healthy both on and off the court and with leading researchers from NIMH to get the latest, need-to-know Finally, as you gather with loved ones this information on anxiety conditions. season, make sure to take a look at our helpful Also in this issue, we provide research updates list of health questions to ask your family. -

Understanding the Mental Status Examination with the Help of Videos

Understanding the Mental Status Examination with the help of videos Dr. Anvesh Roy Psychiatry Resident, University of Toronto Introduction • The mental status examination describes the sum total of the examiner’s observations and impressions of the psychiatric patient at the time of the interview. • Whereas the patient's history remains stable, the patient's mental status can change from day to day or hour to hour. • Even when a patient is mute, is incoherent, or refuses to answer questions, the clinician can obtain a wealth of information through careful observation. Outline for the Mental Status Examination • Appearance • Overt behavior • Attitude • Speech • Mood and affect • Thinking – a. Form – b. Content • Perceptions • Sensorium – a. Alertness – b. Orientation (person, place, time) – c. Concentration – d. Memory (immediate, recent, long term) – e. Calculations – f. Fund of knowledge – g. Abstract reasoning • Insight • Judgment Appearance • Examples of items in the appearance category include body type, posture, poise, clothes, grooming, hair, and nails. • Common terms used to describe appearance are healthy, sickly, ill at ease, looks older/younger than stated age, disheveled, childlike, and bizarre. • Signs of anxiety are noted: moist hands, perspiring forehead, tense posture and wide eyes. Appearance Example (from Psychosis video) • The pt. is a 23 y.o male who appears his age. There is poor grooming and personal hygiene evidenced by foul body odor and long unkempt hair. The pt. is wearing a worn T-Shirt with an odd symbol looking like a shield. This appears to be related to his delusions that he needs ‘antivirus’ protection from people who can access his mind. -

Stuttering & Suicide: Our Experiences & Responsibilities

Stuttering & Suicide: Our Experiences & Responsibilities Judith Kuster, Lisa Scott, Rodney Gabel, Scott Palasik, Joseph Donaher, E. Charles Healey ASHA Chicago, IL November 15, 2013 Judy Kuster Judith Kuster, CCC-SLP, Minnesota State University, Mankato, emeritus professor, M.S. Speech-Language Pathology UW- Madison and M.S. in Counseling MSU, Mankato, ASHA Fellow, SIG 4's steering committee associate coordinator, Stuttering Home Page web weaver and chair of 16 online fluency disorders conferences. She has received ASHF's DiCarlo, IFA's Distinguished Contributor, ISA's Outstanding Contribution, ASHA's Distinguished Contributor, and NSA's Hall of Fame awards. Objectives After completing this activity, participants will be able to identify a relationship between suicide and stuttering identify risk factors of suicide discuss our professional responsibilities regarding suicide prevention and possible role in postvention (dealing with the needs of individuals left after a suicide has been completed). On the 2011 ISAD online conference I asked panel of 25 professionals who specialize in fluency disorders and teach at universities: "Do any of your training programs have a required course where suicide ideation, threats or attempts in clients is discussed?" The silence was deafening. One of the 25 responded affirmatively. Another responded she was now planning to register for a workshop on suicide. After the conference concluded, two more wrote privately and said they had added a section about suicide to their Counseling and Communication Disorders courses. I hope after today, the answer to the question I posed will be more encouraging and also that ASHA will soon recognize the importance of a required course in counseling. -

Chronic Anxiety and Stammering Ashley Craig & Yvonne Tran

Advances in PsychiatricChronic Treatment anxiety (2006), and vol. stammering 12, 63–68 Fear of speaking: chronic anxiety and stammering Ashley Craig & Yvonne Tran Abstract Stammering results in involuntary disruption of a person’s capacity to speak. It begins at an early age and can persist for life for at least 20% of those stammering at 2 years old. Although the aetiological role of anxiety in stammering has not been determined, evidence is emerging that suggests people who stammer are more chronically and socially anxious than those who do not. This is not surprising, given that the symptoms of stammering can be socially embarrassing and personally frustrating, and have the potential to impede vocational and social growth. Implications for DSM–IV diagnostic criteria for stammering and current treatments of stammering are discussed. We hope that this article will encourage a better understanding of the consequences of living with a speech or fluency disorder as well as motivate the development of treatment protocols that directly target the social fears associated with stammering. Stammering (also called stuttering) is a fluency childhood, many recover naturally in early disorder that results in involuntary disruptions of adulthood (Bloodstein, 1995). We found a higher a person’s verbal utterances when, for example, prevalence rate (of up to 1.4%) in children and they are speaking or reading aloud (American adolescents (2–19 years of age), with males in this Psychiatric Association, 1994). The primary symptoms of the disorder are shown in Box 1. If the symptoms are untreated in early childhood, Box 1 Symptoms of stammering there is a risk that the concomitant behaviours will become more pronounced (Bloodstein, 1995; Craig Behavioural symptoms • et al, 2003a). -

Fluency Disorders and Asperger Syndrome Are They Stuttering

FLUENCY DISORDERS AND ASPERGER SYNDROME ARE THEY STUTTERING? EUROPEAN SYMPOSIUM ON FLUENCY DISORDERS FRIDAY MARCH 9 2012 Autism spectrum disorder Pervasive Developmental Disorder Autism PDD – NOS Asperger Syndrome Childhood Disintegrative Disorder Rett’s Syndrome AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER Profound (severe) Autism Moderate Mild (High Functioning ) Asperger Syndrome Autism Spectrum Measured I.Q. Severe Mental disability Gifted Social- Emotional Interaction Aloof Passive Active but Odd Communication Non-verbal Verbal Motor skills Uncoordinated Coordinated Sensory Hypo Hyper WHAT IS ASPERGER SYNDROME? DEFINITION Asperger syndrome (AS) is a disorder described in DSM-IV has having: qualitative impairment in social interaction restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviour interests and activities causing clinically significant impairments in several areas of functioning an unusual prosody and pitch and motor mannerisms are also observed DSM-IV Background “Our earliest understanding of Asperger syndrome (AS) is attributed to Hans Asperger a Viennese physician. In 1944, Asperger described a group of children who exhibited social peculiarities and social isolation, albeit with average cognitive and language development. Based on these characteristics, Asperger stated that his sample represented an independent and distinct clinical condition” (Miles & Simpson, 2002, p. Hans Asperger 132). COMMON TRAITS & CHARACTERISTICS socially awkward and clumsy naive and gullible unaware of others' feelings unable to carry on conversation easily upset -

A Review on Stuttering and Social Anxiety Disorder in Children

STUTTERING AND SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER 102 A Review on Stuttering and Social Anxiety Disorder in Children: Possible Causes and Therapies/Treatments Nadia Nathania [email protected] University of Nottingham Ningbo China Ningbo, China Abstract In the past two decades, stuttering and its relation to social anxiety disorder have been researched using different approaches in study fields such as neurolinguistics and neuropsychology. This paper presents a review of research publications about social anxiety disorder in children who stutter. It takes into account studies of stuttering, social anxiety disorders, the possible causes as well as atti- tudes and beliefs towards stuttering. Also, therapies or treatments that have been conducted on both English-speaking children who stutter in the Western context and Mandarin-speaking children stut- terers in Asia, Taiwan in particular; will be looked at. Keywords: stuttering, stammering, social anxiety disorder, children, therapies, treatments, English speakers, Mandarin speakers. Introduction Stuttering or stammering is a language childhood and continues in adulthood, relat- disorder in which there is disturbance in the ed to many different brain structures. The speech flow, preventing an individual from second is neurogenic stuttering, acquired in communicating effectively (World Health adulthood due to a neurological event as a Organization 2010; Iverach and Rapee, result of stroke, brain injury or trauma. The 2014). It is most commonly associated with third is psychogenic stuttering, which is a involuntary repetition of sounds, syllables, rare form that arises after severe emotional phrases and words (Carlson, 2013). A stut- trauma. The impact of stuttering on the terer usually becomes unable to produce emotional state of an individual can be se- sounds, which includes pauses or blocks vere, which may lead to fear of stuttering in before speech, and prolongs vowels or sem- social situations, anxiety, stress, and being a ivowels in an attempt to produce fluent target of bullying especially in children. -

The Occurrence of Fluency Disorders in Individuals with Down Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorders

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Williams Honors College, Honors Research The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors Projects College Spring 2021 The Occurrence of Fluency Disorders in Individuals with Down Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorders Julia Thomas [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects Part of the Disability Studies Commons, Language Description and Documentation Commons, Semantics and Pragmatics Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Thomas, Julia, "The Occurrence of Fluency Disorders in Individuals with Down Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorders" (2021). Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects. 1255. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/honors_research_projects/1255 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Dr. Gary B. and Pamela S. Williams Honors College at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Williams Honors College, Honors Research Projects by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fluency Disorders and DS/ASD 1 “The Occurrence of Fluency Disorders in Individuals with Down Syndrome and Autism Spectrum Disorders” Honors Research Project Author: Julia Thomas Sponsor: Dr. Scott Palasik, PhD, CCC-SLP April 23rd, 2021 Fluency Disorders and DS/ASD 2 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………..............……………. pg. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………….................…… pg. 3 Explanation of Fluency Disorders………………………………………...............….……… pg. -

A Review on Stuttering and Social Anxiety Disorder in Children

STUTTERING AND SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER 102 A Review on Stuttering and Social Anxiety Disorder in Children: Possible Causes and Therapies/Treatments Nadia Nathania [email protected] University of Nottingham Ningbo China Ningbo, China Abstract In the past two decades, stuttering and its relation to social anxiety disorder have been researched using different approaches in study fields such as neurolinguistics and neuropsychology. This paper presents a review of research publications about social anxiety disorder in children who stutter. It takes into account studies of stuttering, social anxiety disorders, the possible causes as well as atti- tudes and beliefs towards stuttering. Also, therapies or treatments that have been conducted on both English-speaking children who stutter in the Western context and Mandarin-speaking children stut- terers in Asia, Taiwan in particular; will be looked at. Keywords: stuttering, stammering, social anxiety disorder, children, therapies, treatments, English speakers, Mandarin speakers. Introduction Stuttering or stammering is a language childhood and continues in adulthood, relat- disorder in which there is disturbance in the ed to many different brain structures. The speech flow, preventing an individual from second is neurogenic stuttering, acquired in communicating effectively (World Health adulthood due to a neurological event as a Organization 2010; Iverach and Rapee, result of stroke, brain injury or trauma. The 2014). It is most commonly associated with third is psychogenic stuttering, which is a involuntary repetition of sounds, syllables, rare form that arises after severe emotional phrases and words (Carlson, 2013). A stut- trauma. The impact of stuttering on the terer usually becomes unable to produce emotional state of an individual can be se- sounds, which includes pauses or blocks vere, which may lead to fear of stuttering in before speech, and prolongs vowels or sem- social situations, anxiety, stress, and being a ivowels in an attempt to produce fluent target of bullying especially in children. -

Somatosensory Phenomena in Huntington's Disease

Movement Disorders Vol. 3, No. 4, 1988, pp. 343-346. (B 1988 Movement Disorder Society Brief Report Somatosensory Phenomena in Huntington’s Disease Roger L. Albin and Anne B. Young Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. Summary: Sensory symptoms are generally not associated with Huntington’s disease (HD). We describe two patients with HD who had painful somatosensory symptoms. One patient also had auditory hallucinations. No other cause was found for these symp toms. Both patients also had significant depression and one patient committed suicide. Somatosensory symptoms may be a marker for depression in HD. Key Words: Hunting- ton’s disease-Somatosensory symptoms-Depression. Huntington’s disease (HD) is characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance of neu- ropsychiatric dysfunction, chorea, and other movement disorders. Sensory phenomena have not been associated with HD, although pathologic abnormalities have been docu- mented in the thalamus and posterior columns of HD cases (1-3). Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) are also abnormal in HD (4). In Bruyn and Went’s recent review of HD, sensory phenomena are not mentioned (5); Hayden, in his monograph, states that “there have been no reports of obvious sensory defects in Huntington’s chorea” (6). Folstein et al. have reported two patients with auditory hallucinations and interpreted these aural symptoms as the manifestation of an associated psychiatric disturbance (7). We have encountered two HD patients with signifcant somatosensory symptoms and no other evident explanation for the occurrence of these symptoms. One of these patients also had auditory hallucinations. These two patients represent a small fraction of the approximately 150 HD patients seen in our movement disorders clinic over the past 8 years. -

FREELY-AVAILABLE ONLINE TREATMENT MATERIALS for STUTTERING 2016 by Judy Maginnis Kuster

FREELY-AVAILABLE ONLINE TREATMENT MATERIALS FOR STUTTERING 2016 by Judy Maginnis Kuster Disclaimer: The URLs on the handout were all functioning May 2016. Because of the nature of the Internet, there is no guarantee they will be functioning in the future. If the URL doesn’t work, the site listed may be gone -- check the Wayback Machine - http://web.archive.org TREATMENT IDEAS AND ACTIVITIES ONLINE • ASHA’s Guidelines – Treatment of Childhood Stuttering http://www.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589935336§ion=Treatment Approaches To Therapy • Listing of many commercial therapy programs by Judy Kuster http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/kuster/therapy.html#approaches • Posters and PowerPoint on various stuttering therapy programs Charlie Osborne's and Linda Hallen's class projects http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/kuster/journal/journal.html • Manual for the Lidcombe Program - 2010 http://sydney.edu.au/health- sciences/asrc/docs/lp_treatment_guide_2010.pdf - 16 pages • Manual for the Camperdown Program - 2012 http://sydney.edu.au/health- sciences/asrc/docs/camperdown_manual_april_2012.pdf - 21 pages • A Model for Manipulating Linguistic Complexity in Stuttering Therapy by E. Charles Healey, Lisa Scott Trautman and James Panico http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad4/papers/healey4.html Model http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad4/papers/handout.pdf • Study Guide for Charles Van Riper's The Treatment of Stuttering by Darrell Dodge http://www.veilsofstuttering.com/documents/vriper.htm Writing goals and objectives • IEP Goal Bank http://www.speakingofspeech.com/IEP_Goal_Bank.html#Fluency -

A New Model of Huntington's Disease

NEWSFRONTS A new model of Huntington’s disease Defects in oral communication are asso- their v ocalizations are innate, not learned. ciated with many neurological disorders, That’s what makes songbirds so special.” including Huntington’s disease. Despite Liu and colleagues generated transgenic their prevalence, the underlying causes finches harboring mHTT and examined of these communication deficits remain the effects on vocal communication. By unclear. Using zebra finch song birds and analyzing the songs of these mutant birds, transgenics, researchers at Rockefeller they found that compared to wild-type University (New York, NY) have estab- zebra finches, the transgenic mutants dis- lished an important link between mHTT, a played a notable defect in song learning. gene known to cause Huntington’s disease Their songs contained incorrect sylla- in humans, and vocal communication (Nat. bles, long repeats and stuttering, and these domi8nic/iStock/Thinkstock Neurosci. 18, 1617–1622; 2015). defects worsened with age. These findings Zebra finches are a popular model sys- suggest that the neuronal circuits respon- dopamine and androgen receptors and the tem for scientists studying language and sible for song learning were not intact in presence of mHTT protein aggregates in communication. Zebra finches learn mHTT mutants. To test this hypothesis, the brain. The authors propose that these songs by mimicking the song of a ‘tutor’, the authors created lesions in areas of the abnormalities could have contributed to the or adult finch, similar to the way human brain known to have a role in song learn- impaired song production. children acquire language from their ing. Although lesions to these brain circuits Liu noted the far-reaching implications parents. -

Case Study of a 13-Year-Old Boy Suffering from Depression and Stuttering

Péter Lajos Eötvös Loránd University, „Bárczi Gusztáv” Faculty of Special Education, Budapest, Hungary Case Study of a 13-year-old Boy Suffering from Depression and Stuttering Abstract: Studium przypadku trzynastolatka cierpiącego na depresję i jąkającego się. Przyczyną za burzeń emocjonalnych, niepłynności mowy i depresji chłopca są jego przeżycia z wczesnego dzie ciństwa – chłopiec w wieku trzech lat został oddzielony od matki. Słowa kluczowe: jąkanie, psychologia kliniczna, depresja, separacja, samobójstwo Introduction In clinical practice there is a frequently occurring problem, namely, who has the competence to treat stuttering. Speech therapists often think that – because of the emotional background of stuttering – it is better to refer children who stut ter to psychotherapy. In spite of this, psychologists regard stuttering as a speech problem and send back children who stutter to the speech therapist. As we know speech therapy can develop the fluency of speech, communication ability, self expression, selfcompetence, and finally can reduce or eliminate the symptoms of stuttering. Although children who stutter may have serious emotional problems, and speech therapists – after a complex examination – have to decide who is com petent in the treatment. This paper presents the diagnostic process of a 13yearold boy who stutters and suffers from depression in order to outline the competence of a speech therapist in the treatment of people who stutter. 20 Część pierwsza: Prace naukowo-badawcze Childhood depression Depression affects people of all ages, including children and young people. Depression among schoolaged children is becoming increasingly commonplace. Children and adolescents with major depressive disorder are much more likely to commit suicide.