Resilience in an Urban Social Space: a Case Study of Wenceslas Square

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Events That Led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and Its Immediate Aftermath

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2015 Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath Natalie Babjukova Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Recommended Citation Babjukova, Natalie, "Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2015. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/469 Events that led to the Czechoslovakian Prague Spring and its immediate aftermath Senior thesis towards Russian major Natalie Babjukova Spring 2015 ` The invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Soviet Union on August 21 st 1968 dramatically changed not only Czech domestic, as well as international politics, but also the lives of every single person in the country. It was an intrusion of the Soviet Union into Czechoslovakia that no one had expected. There were many events that led to the aggressive action of the Soviets that could be dated way back, events that preceded the Prague Spring. Even though it is a very recent topic, the Cold War made it hard for people outside the Soviet Union to understand what the regime was about and what exactly was wrong about it. Things that leaked out of the country were mostly positive and that is why the rest of the world did not feel the need to interfere. Even within the country, many incidents were explained using excuses and lies just so citizens would not want to revolt. Throughout the years of the communist regime people started realizing the lies they were being told, but even then they could not oppose it. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1987 BERLINART: 20 FILMS June 11 - September 5, 1987 BERLINART: 20 FILMS, the film component of The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition BERLINART: 1961-1987, reflects the integral role of film in the Berlin art community. Organized by Laurence Kardish, curator in the Department of Film, the thirteen programs include fiction and nonfiction works by more than twenty filmmakers. These films, made between 1971 and 1987, relate to various aspects of Berlin life. The filmmakers represented here have responded in a variety of ways to the cultural, political, and economic conditions resulting from Berlin's unique geographic position. They explore the psychological, spiritual, and social issues of contemporary life in Berlin, working in an environment supported by a progressive film and television academy, as well as alternative distributors and exhibitors. Federal and municipal grants and production money from German television have also attracted German and American filmmakers to West Berlin. BERLINART: 20 FILMS, beginning June 11 and continuing through September 5, 1987, opens with Helma Sanders-Brahms's romantic drama Laputa (1986), starring Sami Frey and Krystyna Janda. The film, in which Berlin is compared to the floating island Laputa in Swift's Gulliver's Travels, depicts the city as a transit station for the brief encounters of two foreign lovers. The peculiar geography, topography, and architecture of Berlin also figure strongly in Alfred Behrens's Images of Berlin's City Railway (1982), a poetic exploration of the vast, largely unused public transit that connects East and - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019-5486 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART - 2 - West Berlin; and Elf1 Mikesch's Macumba (1982), a mystery in which the city's haunting interior spaces seem to determine the actions and moods of the characters. -

Political Stability and the Division of Czechoslovakia

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-1996 Political Stability and the Division of Czechoslovakia Timothy M. Kuehnlein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kuehnlein, Timothy M., "Political Stability and the Division of Czechoslovakia" (1996). Master's Theses. 3826. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3826 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICAL STABILITY AND THE DIVISION OF CZECHOSLOVAKIA by Timothy M. Kuehnlein, Jr. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 1996 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The completion of this project was both a tedious and rewarding experience. With the highest expectations for the style and content of the presentation, I have attempted to be as concise yet thorough as possible in the presentation and defense of the argument. The composition of this thesis entails nearly two years of diligent work outside of general course studies. It includes preliminary readings in Central and East European affairs, an extensive excursion throughout the Czech and Slovak republics with readings in the theory of political stability, the history and politics of Czecho slovakia, in addition to composing the text. My pursuit was driven by a passion for the topic, a quest for know ledge and understanding, and the argument's potential for continued development. -

Pressemitteilung

Pressemitteilung Editorial TAGESSPIEGEL supplement The Bode-Museum and the Period of Rediscovery Prof. Peter-Klaus Schuster General Director of the National Museums in Berlin Seite 1 von 5 Staatliche Museen The re-opening of the Bode-Museum on 17th October 2006 sees the zu Berlin Generaldirektion general restoration and complete refurbishment of the second Stauffenbergstraße 41 building of the Berlin Museum Island to the opened again to the 10785 Berlin public. One can confidently say that the National Museums in Berlin are experiencing a story of great success. With the temple of the Dr. Matthias Henkel National Gallery standing on a prominent plinth alongside the Unter Leiter Öffentlichkeitsarbeit den Linden thoroughfare and very quite visible from the Lustgarten, matthias.henkel@ smb.spk-berlin.de the actual beginning of the Museum Island to the rear of Schinkels Altem Museum, the presently restored Bode-Museum forms a no less Anne Schäfer-Junker spectacular full ending to the Museum Island on its northern tip. Pressekontakt a.schaefer-junker@ For the first time, with the opening of the Bode-Museum, formerly the smb.spk-berlin.de Kaiser Friedrich Museum, the complete dimensions of the Berlin Museum Island are once again opened up to be experienced as a Tel +49(0)30-266-2629 Fax +49(0)30-266-2995 living organism. For it is indeed eight years since the Museum Island was split in two by the railway line: into one chaotic vibrant part, on the one hand, with almost two million visitors yearly to the area www.smb.museum/presse extending to the Pergamon Museum situated in front of the railway line, and on the other hand the quasi extinct area undergoing many www.MuseumShop.de years of building and restructuring on the other side of the tracks where the Bode-Museum sat shaded from the light – lifeless and shut up. -

Past & Present in Prague and Central Bohemia

History in the Making Volume 10 Article 9 January 2017 Past & Present in Prague and Central Bohemia Martin Votruba CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Votruba, Martin (2017) "Past & Present in Prague and Central Bohemia," History in the Making: Vol. 10 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol10/iss1/9 This Travels through History is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Travels Through History Past & Present in Prague and Central Bohemia By Martin Votruba While I was born and raised in Southern California, my parents migrated from, what was then, Czechoslovakia in the late 1960’s – when Communism control intensified and they felt threatened. They left behind family members in Prague, and in a couple smaller outlying towns, and relocated to Los Angeles, California. Growing up, we only spoke Czech at home; my parents reasoned that I would learn and practice plenty of English at school. I have always been proud of my family roots and I am grateful to retain some of the language and culture. In the early 1980s, while Czechoslovakia was still under communist control, my parents sent me there to visit some of the family they left behind. I spent about six weeks with aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents in and around Prague. -

The Architecture of Berlin: Innovations, Confrontations and Redefinitions

Course Title The Architecture of Berlin: Innovations, Confrontations and Redefinitions Course Number SOC-UA.9941001, ART-UA.9651001 SAMPLE SYLLABUS Instructor Contact Information Dr. phil. habil. Paul Sigel [email protected] Course Details Mondays, 2:00pm to 4:45pm Location of class: NYU Berlin Academic Center, Room “Prenzlauer Berg” (tbc) Tour meeting locations will be announced; please check your email the day before the class. Prerequisites None Units earned 4 Course Description Berlin's urban landscape and architectural history reflect the unique and dramatic history of this metropolis. Rarely has any city experienced equally radical waves of growth and destruction, of innovation and fragmentation and of opposing attempts at urban redefinition. Particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the city developed into a cultural and industrial metropolis. Berlin, the latecomer among European metropolitan cities, became a veritable world city with an outstanding heritage of baroque, classicist and modern architecture. Destruction during the Second World War and the separation of the city led to opposing planning concepts for its reconstruction, which contributed to significant new layers of the urban pattern. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, a major building boom made Berlin a hotspot for often controversial building and planning debates. This course will enable students to see, describe and understand the complex historical, cultural and social conditions of the different layers of Berlin's architecture. Course Objective 1. This course is an introduction to Berlin's architectural history, as well as an introduction to methods of describing and reflecting upon architecture and built urban spaces. Students will gain a differentiated understanding of the form, function and style categories used in art 1 history. -

Prague Castle Classic River Boat Nábř

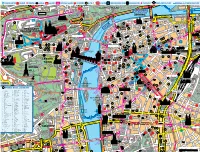

122 TOURIST CENTRE MUSEUM THEATRE CHURCH GALLERY NG NATIONAL GALLERY MONUMENT HOTEL HOSPITAL PEDESTRIANIZED ZONE UNDERGROUND TRAM STOP WALKS MEETING POINT BOAT DEPARTURE POINT 8 53 Štefánikův Bridge LUNCH/DINNER BOAT eše CRUISE DEPARTURE 14 Tram stop 22 for easy access to Prague Castle Classic River Boat nábř. Edvarda Ben 6 Pražský 22 hrad Čechův Bridge Postal 45 Museum 43 56 89 St. Agnes 12 sq. Convent Golden Lane 53 Old Castle Stairs JAZZ BOAT JEWISH 20 5 s DEPARTURE HRADČANY The Office TOWN St. Peter r St. George’ sq. Church PRAGUE CASTLE Basilica sq. 26 79 123 of the Government Synagogu Old-New Spanish St. Castullus St. Vitus Synagogue Church All 72 Cathedral Prague Saints 58 Prague Castle Valdštejnské City square e Kotva 69 52 Museum Complex Mánesův VltavaBridge Rive 26 99 14 square 114 Shopping 18 Castle Stairs 117 16 Mall 75 Bus Station square sq. 50 Florenc Maiselova St. James Palladium 113 11 the Greater 25 Shopping Mall 80 107 101 Church 64 EXC 111 Meeting 76 Žatecká 44 42 110 Point 83 103 19 HANGE St. Nicholas Church 24 29 7 Franz Republic 71 St. Nicholas sq. Franz Kafka Kafka sq. 48 Museum 39 sq. Church Old Týn Station Town PowderMunicipal Mariánské SquareChurch Gate House 78 sq. 15 Astronomical 21 60 Lennon 97 MaléClock 40 23 109 Wall OLD sq. 115 TOWN 112 30 sq. sq. sq. 121 sq. 1 14 Havelský 62 108 Market 73 102 Na Příkopě Strahov Jubilee 70 54 St. ChurchHavel Monastery PETŘÍN Museum 38 Synagogue of Music KAMPA 82 Hunger W HILL ISLAND 118 65 sq. -

Free-Map.Pdf

122 TOURIST CENTRE MUSEUM THEATRE CHURCH GALLERY NG NATIONAL GALLERY MONUMENT HOTEL HOSPITAL PEDESTRIANIZED ZONE UNDERGROUND TRAM STOP WALKS MEETING POINT BOAT DEPARTURE POINT 8 15 Štefánikův Bridge LUNCH/DINNER BOAT eše CRUISE DEPARTURE 14 Tram stop 22 for easy access to Prague Castle Classic River Boat nábř. Edvarda Ben 6 Pražský 22 23 hrad 23 Čechův 15 Bridge Postal 45 Museum 43 56 23 89 St. Agnes 12 sq. Convent Golden Lane 53 Old Castle Stairs JAZZ BOAT JEWISH 20 5 s DEPARTURE HRADČANY The Office TOWN St. Peter r St. George’ sq. Church PRAGUE CASTLE Basilica sq. 26 79 123 of the Government Synagogu Old-New Spanish St. Castullus St. Vitus Synagogue Church Cathedral All 72 Saints 6 Prague Valdštejnské 58 24 City Prague Castle 2- e square Kotva 69 52 Museum Complex Mánesův VltavaBridge Rive 26 99 14 square 114 Shopping 18 Castle Stairs 117 16 Mall 75 Bus Station square sq. 15 50 Florenc Maiselova St. James Palladium 107 113 15 11 the Greater 25 Shopping Mall 80 101 23 Church 64 EXC 111 Meeting 76 Žatecká 44 42 110 Point 83 103 19 HANGE St. Nicholas Church 29 7 Franz Republic 71 St. Nicholas sq. Franz Kafka Kafka sq. 48 Museum 39 sq. Church Old Týn Station Town PowderMunicipal Mariánské SquareChurch Gate House 78 sq. 15 Astronomical 21 60 Lennon 97 MaléClock 40 23 109 Wall OLD sq. 115 TOWN 112 30 sq. -15 sq. sq. 121 sq. 1 14 Havelský 62 108 Market 2 73 Na Příkopě 12 102 Strahov Jubilee 70 54 St. -

CHAPTER 6 After the Turbulent Events of the Famous Wende—The Fall Of

CHAPTER 6 UNIFIED BERLIN: THE NEW CAPITAL After the turbulent events of the famous Wende—the fall of the Wall on 9 November 1989, the reunification of Germany on 3 October 1990, and the election of Berlin as the seat of government and the parliament on 20 June 1991—Berlin has victoriously emerged as Germany’s new/old capital. But it remains a city in flux, a topography marked by a ghostly history, an unpredictable future, and a prolonged identity crisis. Still, these are the very features that make contemporary Berlin one of the most exciting cities to study and to visit. Even though we should not simply assume that Berlin is typical of German society and German history in its entirety, the capital reflects many aspects of Germany’s post-reunification culture and its role in the New Europe. Berlin is also representative of metropolitan life in our age of late capitalist consumer culture, multiculturalism, and the global economy. In this chapter, we will again explore the German capital in the spirit of the flaneur, the leisurely city stroller who “reads” the streets, squares, buildings, and people of the great European capitals like a text, deciphering them as symbolic signs of history, social life, politics, and culture. Certainly, Berlin has been ravaged by the bombings of World War II and was further victimized by the cold war division into the capital of the GDR and a Western part heavily subsidized by West Germany. The city therefore lacks the densely built city space of Paris, London, Moscow, or even New York, to name just a few typical haunts of the classical flaneur. -

IGU WOC4 Meetings March 3Rd—6Th, 2015 Prague, Czech Republic Contents

IGU WOC4 Meetings March 3rd—6th, 2015 Prague, Czech Republic Contents Social programme for Accompanying persons .................................................... 3 Hotel Adria ................................................................................................................. 4 Prague ........................................................................................................................ 7 Miscellaneous Information ....................................................................................... 10 Social programme for Accompanying persons Social programme for Accompanying persons Wednesday, March 4th, 2015 8:50 a.m. Meet with an English-speaking guide at the lobby of the hotel Adria Accompanying Persons 9:00 a.m. — 1:00 p.m. Guided City Walk — Prague Castle, Lesser Town, Charles Bridge, Accompanying Persons Jewish Prague (4 hours, including lunch) route: Adria Hotel — Wenceslas Square, metro transportation to Hradcanska metro station, on foot Pisecka Gate, Belveder Summer House, Royal Garden, Prague Castle, Old Royal Route, Lesser Town, Charles Bridge, Jewish Prague, Adria Hotel Thursday, March 5th, 2015 8:50 a.m. Meet with an English-speaking guide at the lobby of the hotel Adria Accompanying Persons 9:00 a.m. — 1:00 p.m. Guided City Walk — Vysehrad and New Town Accompanying Persons (4 hours, including lunch) route: Adria Hotel Wenceslas Square, metro transfer to Vysehrad, walking round the Vysehrad (historical fort), Vltava River Embankments, New Town, National Theatre, Charles Square, New Town Hall, Adria Hotel IGU WOC4 Meetings 3 Hotel Adria Hotel Adria HOTEL ADRIA PRAGUE http://www.adria.cz/en/ Hotel Adria****, Václavské náměstí 26, The Adria Hotel offers luxury 110 00 Praha 1, Czech Republic accommodation in 89 rooms with a view of the vibrant Wenceslas Square or the serene The Adria Hotel is a green four star Superior Franciscan Garden, a cheerfully equipped hotel on Wenceslas Square in the centre of breakfast room with lots of home produce, Prague. -

The Story of Journalist Organizations in Czechoslovakia

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183–2439) 2017, Volume 5, Issue 3, Pages 95–102 DOI: 10.17645/mac.v5i3.1042 Article The Story of Journalist Organizations in Czechoslovakia Markéta Ševčíková 1,* and Kaarle Nordenstreng 2 1 Independent Researcher, Prague, Czech Republic; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Faculty of Communication Sciences, University of Tampere, 33014 Tampere, Finland; E-Mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Submitted: 15 May 2017 | Accepted: 23 August 2017 | Published: 27 September 2017 Abstract This article reviews the political history of Czechoslovakia as a vital part of the Soviet-dominated “Communist bloc” and its repercussions for the journalist associations based in the country. Following an eventful history since 1918, Czechoslovakia changed in 1948 from a liberal democracy into a Communist regime. This had significant consequences for journalists and their national union and also for the International Organization of Journalists (IOJ), which had just established its head- quarters in Prague. The second historical event to shake the political system was the “Prague Spring” of 1968 and its aftermath among journalists and their unions. The third landmark was the “Velvet Revolution” of 1989, which played a significant part in the fall of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe and led to the closing of the old Union of Journalists in 1990, followed by the founding of a new Syndicate which refused to serve as the host of the IOJ. This led to a gradual disintegration and the closing down of what in the 1980s was the world’s largest non-governmental organization in the media field. Keywords Cold War; communism; Czechoslovakia; International Organization of Journalists; journalism; union of journalists Issue This article is part of the issue “Histories of Collaboration and Dissent: Journalists’ Associations Squeezed by Political System Changes”, edited by Epp Lauk (University of Jyväskylä, Finland) and Kaarle Nordenstreng (University of Tampere, Finland). -

Guided Tour of Prague Idols and Where Today Stands While Enjoying a Beer Or Coffee Attraction

Prague TOP 10 Charles Bridge Old Town Square Prague is said to be the The Golden Lane “heart of Europe” and is sometimes called the “mother 1. Prague Castle 4. Charles Bridge Climb the Old Castle Steps Take an early morning walk of cities”. Over the centuries, to Prague Castle and visit its across the medieval stone courtyards and the interiors bridge, before its magnificent people have invented such of the Old Royal Palace. From Baroque statues are besieged St. Vitus Cathedral, head to by crowds of tourists. nicknames for Prague as the the Golden Lane – a former haven for alchemists and 5. Old Town Square with City of a Hundred Spires, charlatans. the Astronomical Clock Golden Prague or Magic 2. Vyšehrad Do not forget that the Old Town Square is the true heart Prague – always celebrating Soak up the atmosphere of Prague. What’s more, at the of the Vyšehrad fortified top of every hour you can see its architectural and spiritual settlement, where before the a procession of the Apostles richness and its mystical arrival of Christianity pagan on the Old Town Hall princes prayed to their forest Astronomical Clock! Then, A guided tour of Prague idols and where today stands while enjoying a beer or coffee attraction. You will discover We will lead you to famous 7. The Infant Jesus 9. Petřín Hill one of the most beautiful under Baroque arcades, you of Prague the glorious history of this monuments and places churches in Prague. can watch the bustle on the Surrounded by trees on the full of history and also trace square and admire the towers Visit the Church of Our Lady top of Petřín, you will forget the footsteps of celebrated former imperial and royal city, 3.