View the DCR Trail Guidelines and Best Practices Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

¬«27 ¬«16 ¬«27 ¬«16 ¬«16 ¬«27 ¬«27

(!T # # # (!T # # !i South Natick N ' N # at 6 ick 1 Sh ° er 2 b or 4 B n P e P Charles River r ro S ry sp # t ec Everett St Link Trail P t 27 lea ! St «¬ sa Peters Hill er n v S t Rd Town i t ill H R !i H u L 16 s !i h n Forest ak «¬ le Mumford s t e Broadmoor r ru in S a B g t h Wildlife Pegan ! t N ' L # Wildlife C Forest Hill S 5 n Brush Hill # 1 Little Farm Sanctuary n i ° Natick !i a 2 A G # !i Pond Res. 4 r D Dover M e t e C Little n # Town S Farm !i n L Pine Pond n Forest e l W Hill G e # Farm Rd L Peters s a t t t Sherborn S e S k Reservation rm Dover e r le a n F ap # M S A 16 t v «¬ 27 # Miller Hill N ' e «¬ # 4 Town Farm !i 1 ° Pond 2 n Hildreth Forest t r 4 t S o res b Res. Bailey Fo r r Goulding E e e # h v Oak Hill Res. St Rocky S o Chase # !i D # Narrows Woodlands Charles River t S # Link Trail e oodla tr W n d St F n Snow Hill S Medfield a e r C 16 o m u N «¬ Rocky State ' t S h 3 F Narrows Forest t 1 M ° Dover 2 a 4 i # n !i Medfield Medfield S State t t S Hospital g Rocky Woods !i n N # # !i !i i o d Reservation r r B # t a h u C H l h S l a a t r r !i d le s S N R ' t i G 2 v 1 e r ° ! 2 4 # Ce ntr South End 27 al S orn Pond «¬ t Sherb «¬115 llis Bridge on Mi Medfield # llist M Island t St Ho id Bogastow Wes dle 109 se Brook Meadows «¬ x St N ' ! # 1 1 ° 2 Millis nd Rd t 4 a sl d S H I Park R y r e 109 a v «¬ w o e M D M er s e i iv u l R a !i d l s i rle C Medfield w s ha a Millis C y Rhodo- t dendrons N S ' t Shattuck 0 Bay Circuit Trail h K t 1 S u ° 27 o 2 Map 9 No ¬ e Res. -

Neponset River Watershed Protecting Our Water, Wildlife and Land

!"a$ QÈQÈ Neponset River Watershed Boston Protecting Our Water, Wildlife and Land There’s a lot going on in your watershed! QÂ • Fourteen cities & towns • Over 120 square miles QÂ Dorchester • 330,00+ people Visit us to learn more: QÂQÂ !"d$ ive !"d$ ponset River www.neponset.org Mattapan Neponset r Quincy QÈ ty k quity Bk Unqu e B n e e U Hyde Park re T r T Q} e !"c$ Qæ e n i !"c$ n Q¼ i P QÅ P Milton M o otther Dedham r ver QÒ Riive QÒ t R QÈ Westwood et QÑ s e M n s M o n Dover i p o ill e p l e l N PPl N laan Iq nti Iq tinng gfi P fie P eld u !"c$ l ur !"c$ d B rg Bk ga k at Qi to Medfield Qi or k ry o k y B o o B r k o y r k y B n Ponkapoag l B n Ponkapoag a l l P a Pond i l Pe Pond i m Norwood ec m cu M r un Qã M r e nit Randolph e i !"d$ t B onkapoag Bk Qæ G !"d$ Bk Ponkapoag Bk G P Q¸ k QÑ QÛ QÑ H Canton H Willett a Willett a PondPond ww ees s Reservoir MM Ip Pond ini k ne B e t QÆ B i t QÆ B E i QÉ r e E u ro l e u oo l a q o r h o a e q k t ive o s e k set R Traph st P QÅ Qz ponnse Trap t P QÅ NNeepo QÒ Qi er Meadow QÒ eaver Mea w B Walpole Be k QÏ S Sppr rin ing g k B B g B Iq k ag Qz k poa S sap Ste QÑ ass ee QÑ a p QÆ M H il Qp lll S B Qã Q} Sc k k chho Bk oo r B ol er lM v e Stoughton r M a v QÉ e r e e a ea e v e a B i v d B Sharon i d R o o R w t w QÆ e t B e s B s n k n k o o p p e !"d$ e !"d$ N Lake N Massapoag Legend Foxborough Canoe Launches NeponsetNeponset Reservoir QÅ Reservoir QÅ Ponds/Ocean Qz Streams Q¸Q¸ Parks/Conservation QÇ Towns Qæ 0 0.5 1 2 QÉ Miles IpIp QÆ QÒ QÑ %&l( Qv Qf Qz Q¸ A watershed is the area of land that drains The Watershed includes parts of 14 cities successful campaign to clean up and into a particular river, stream, or pond. -

Map 1A - Newburyport, Newbury, Rowley - Skirting the End of the Airport's Grassy Runway BAY CIRCUIT TRAIL Route (CAUTION: This Is an Active Runway

Disclaimer and Cautions: The Bay Circuit Alliance, as the advocate and promoter of the Bay Circuit Trail, expressly disclaims responsibility for injuries or damages that may arise from using the trail. We cannot guarantee the accuracy of maps or completeness of warnings about hazards that may exist. Portions of the trail are along roads or train tracks and involve crossing them. Users should pay attention to traffic and walk on the shoulder of roads facing traffic, not on the pavement, cross only at designated locations and use extreme care. Children and pets need to be closely monitored and under control. Refuge headquarters across the road. The BCT continues from the south side of the road just at the end of the Plum Island airport (an historic site). A signboard here usually has brochures about the BCT in Newbury. Proceed south on the Eliza Little Trail , Map 1A - Newburyport, Newbury, Rowley - skirting the end of the airport's grassy runway BAY CIRCUIT TRAIL route (CAUTION: this is an active runway. Keep to the (as shown on map dated March 2013) edge and keep dogs on leash ). Then go right on a (text updated May 2014) cart rd through high grass and through the fields of the Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm (bicycles not The BCT often follows pre-existing local trails; BCT- allowed). specific blazing is a work in progress and may be sparse 2.5 Pass through a gate south (left) of the historic in segments. We encourage you to review and carry Spencer-Peirce-Little Manor House , open to the corresponding local maps on your BCT walk. -

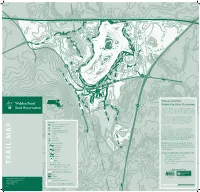

Walden Pond R O Oa W R D L Oreau’S O R Ty I a K N N U 226 O

TO MBTA FITCHBURG COMMUTER LINE ROUTE 495, ACTON h Fire d Sout Road North T 147 Fire Roa th Fir idge r Pa e e R a 167 Pond I R Pin i c o l Long Cove e ad F N Ice Fort Cove o or rt th Cove Roa Heywood’s Meadow d FIELD 187 l i Path ail Lo a w r Tr op r do e T a k e s h r F M E e t k a s a Heyw ’s E 187 i P 187 ood 206 r h d n a a w 167 o v o e T R n H e y t e v B 187 2 y n o a 167 w a 187 C y o h Little Cove t o R S r 167 d o o ’ H s F a e d m th M e loc Pa k 270 80 c e 100 I B a E e m a d 40 n W C Baker Bridge Road o EMERSON’S e Concord Road r o w s 60 F a n CLIFF i o e t c e R n l o 206 265 d r r o ’s 20 d t a o F d C Walden Pond R o oa w R d l oreau’s o r ty i a k n n u 226 o 246 Cove d C T d F Ol r o a O r i k l l d C 187 o h n h t THOREAU t c 187 a a HOUSE SITE o P P Wyman 167 r ORIGINAL d d 167 R l n e Meadow i o d ra P g . -

Management Plan 2013

Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area Management Plan 2013 Housattonio c River, Kenene t,, Cononneccticiccut. PhoP tograph by the Houo satoninic Valll eyy AssAss ociiatiion. Prepared by: Upper Housatonic Valley Heritage Area, Inc. June 2013 24 Main Street PO Box 493, Salisbury, CT 06068 PO Box 611 Great Barrington, MA 01257 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Purpose and Need 1 2.6.2 Connections to the Land 15 1.1 Purpose of this Report 1 2.6.3 Cradle of Industry 17 1.2 Definition of a Heritage Area 1 2.6.4 The Pursuit of Freedom & Liberty 19 1.3 Significance of the Upper Housatonic Valley 2.7 Foundations for Interpretive Planning 21 National Heritage Area 1 Chapter 3: Vision, Mission, Core Programs, 1.4 Purpose of Housatonic Heritage 3 and Policies 22 1.5 Establishment of the Upper Housatonic Valley 3 National Heritage Area 3.1 Vision 22 1.6 Boundaries of the Area 4 3.2 Mission 22 3.3 The Nine Core Programs 23 Chapter 2: Foundation for Planning 5 3.4 The Housatonic Heritage “Toolbox” 28 2.1 Legislative Requirements 5 3.5 Comprehensive Management Policies 30 2.2 Assessment of Existing Resources 5 3.5.1 Policies for Learning Community Priorities 30 2.3 Cultural Resources 5 3.5.2 Policies for Decision-Making 32 2.3.1 Prehistoric and Native American Cultural Resources 5 Chapter 4: Development of the Management Plan 33 2.3.2 Historic Resources 7 4.1 Public Participation and Scoping 33 2.4 Natural Resources 9 4.2 Summary of Issues Raised in Scoping 33 2.4.1 Geologic Resources 9 4.3 Management Scenarios 34 2.4.2 Geographic Area 9 4.3.1 Scenario 1: Continue the Nine Core 2.4.3 Ecosystems 10 Programs 34 2.4.4 Conservation Areas for Public 4.3.2 Scenario 2: Catalyst for Sharing Enjoyment 12 our Heritage 34 2.5 Recreational Resources 13 4.3.3 Scenario 3: Promote Regional Economic Vitality and Address 2.6 Interpretive Themes 14 Regional Heritage 35 2.6.1. -

Winter Breeze

The Southeast Breeze Quarterly newsletter of the Appalachian Mountain Club, Southeastern Massachusetts Chapter Winter 2011/2012 — December, January, February View from the Chair By Jim Plouffe, Chapter Chair It‘s been one year; one year since I accepted the position as Chapter Chair for the Chapter. It is the ultimate of volunteer positions, in this type of club. While some volunteers give up a Saturday here or there and some volunteers lead a hike or a bike or a paddle, once in a while, this position, as Chapter Chair, has me running regular meetings, planning club wide events, coordinating weekend events, attending other meetings, annual dinners, retreats, and many other things that take up time. The work as a Chapter Chair goes beyond these ―time taking‖ events and includes the time it takes to prepare agendas, write articles, and collect paperwork and other less noticeable but important tasks that take place behind the scenes. I tell you this, not to pat myself on the back, because I don‘t really need the pat on the back. I enjoy doing this type of work and find it rewarding just to see that I can make a difference in my microcosm. I have told you this because last night I sat in a room with ―my‖ Executive Board and conducted a meeting that will hopefully bring this Chapter forward in the year 2012. At this meeting, I was looking around and realized that for every minute I spend planning, executing and attending my meetings and events, the people in front of me, acting in their volunteer capacity, spent an equal amount of time doing their best to try and achieve the same goals and intentions that I strive to accomplish. -

Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Dedicated to the Preservation, Protection and Enjoyment of the Forest Preserve

The Lookout FEBRUARY-MARCH 2015 Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Dedicated to the preservation, protection and enjoyment of the Forest Preserve http://www.adk-schenectady.org Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Board ELECTED OFFICERS APPOINTED MEMBERS CHAIR: CONSERVATION: Rich Vertigan Mal Provost 1804 Van Cortland St., Rotterdam, NY 12303 93 Kingsbury Road, Burnt Hills, NY 12027 381-9319 399-1565 [email protected] [email protected] LOOKOUT EDITOR: VICE-CHAIR: Nicole Weinstein Stan Stoklosa 904 Myrtle Avenue 8 Archer Drive, Clifton Park, NY 12065 Albany, NY 12208 383-3066 482-2594; [email protected] [email protected]; [email protected] MEMBERSHIP: VACANT SECRETARY: NORTHVILLE-PLACID TRAIL: Sally Dewes Mary MacDonald [email protected] 27 Woodside Drive, Clifton Park, NY 12065 371-1293; [email protected] TREASURER: OUTINGS: Mike Brun Larry Woods 4001 Jockey St., Ballston Lake, NY 12019 1120 7th Avenue 399-1021 Watervliet NY 12189 [email protected] 810-7552; [email protected] PRINTING/MAILING: DIRECTOR: Karen McKenney Norm Kuchar [email protected] 60 Fredericks Road 518-399-6606 Glenville, NY 12302 PUBLICITY: 399-6243 Roy Keats [email protected] 1913 Baker Avenue Schenectady, NY 12309 PROJECT COORDINATORS: 518-370-0399; [email protected] Horst deLorenzi TRAILS: 34 St. Judes Lane, Scotia, NY 12302 Stan Stoklosa 399-4615 8 Archer Drive, Clifton Park, NY 12065 [email protected] 383-3066; [email protected] SILVER LAKE: Jacque McGinn Harold McCumber 79 Kenaware Avenue, Delmar, NY 12054 1074 Madison Avenue, Troy, NY 12180 438-0557 274-3960; [email protected] [email protected] WEB MASTER: Rich Vertigan 1804 Van Cortland St., Rotterdam, NY 12303 381-9319 [email protected] WHITEWATER: Ralph Pascale 50 Johnston Avenue Cohoes, NY 12047 235-1614 [email protected] On the Schenectady Chapter hikers on No. -

BCF Newsletter Layout--November 2001.Qxd

Belmont Citizens Forum Vol. 2, No. 6 A Newsletter for Belmont Residents November 2001 Firehouses Badly Need Repair or Replacement By Sharon Vanderslice in the stations is so out-of-date that, Osterhaus said, if he encountered it during an inspection of a pri- To say that Belmont’s fire stations are held vately owned building, he’d have to cite the owner together with duct tape and glue would be no exag- for code violations. A recent tour revealed exposed geration. Maintenance on these buildings, located wires hanging out of a box in the cellar and exten- on Leonard Street, Trapelo Road, and Fairview sion cords draped under sinks in the bathrooms. Ave., has been deferred for so many years that the The firefighters staff these stations around the firefighters have had to use whatever materials they clock, working 24-hour shifts, and the living condi- could scrounge up to keep the stations habitable. tions are decidedly substandard. Soot from the Eight-inch chunks of horsehair plaster are diesel engines covers the downstairs walls, and falling out of the walls. Floors are buckling and fumes rise to the upper floors where the firefighters tiles are peeling up. Paint is shriveling. Windows sleep and eat. The kitchen at the Waverley station are leaking. Some of the furniture looks as if it was was cobbled together by firefighters who hauled recently rescued from the sidewalk. And this is just continued on page 8 the cosmetic stuff. There are pipes rusting out, slates falling off the roof, and gaps under the main doors that allow snow Table of Contents to blow in during the winter and skunks to sneak in during the summer. -

Rensselaer County Trail Vision Plan

Trail Vision Plan For Rensselaer County Report by the Rensselaer County Alliance for Trails Project Partners Rensselaer Land Trust Rensselaer County Funded in part by the Hudson River Valley Greenway May 2009 Trail Vision Plan For Rensselaer County Special thanks to the following individuals and organizations: Rensselaer County Legislator Brian Zweig for providing the vision for this project; seed money for the project; and enthusiasm and technical support throughout the project; Melissa Barry for organizing the project and serving as the primary author of this report; Rensselaer Land Trust, for sponsoring the grant application to the Hudson River Greenway and for providing grant administration services; John Munn for providing accounting assistance; Rensselaer County Planner Linda von der Heide, for participation, assistance and advice throughout this project; Rensselaer County Executive Kathy Jimino for county support and participation in the project; and the Rensselaer County GIS Department for data. Special thanks to the many individuals who attended one of our trail visioning workshops in April and May of 2008. We would like to acknowledge the following individuals who assisted in the planning process: Melissa Barry Floyd Hunt Doree Cox John Linton Stacy Draper Rik and Beverly McClave Fran Egbert Alan Michaels Emily Ettlinger Barbara Nelson Flora Fasoldt Ann Shaugnessy Arthur Fontijn Linda von der Heide Jim Garrahan Mark Wehnau Dick Gibbs Contents Introduction ___________________________________ page 1 The Purpose of a Vision _________________________ -

Map 6 -Billerica, Bedford, Acton, Carlisle, Concord

Disclaimer and Cautions: The Bay Circuit Alliance, as the advocate and promoter of the Bay Circuit Trail, expressly disclaims responsibility for injuries or damages that may arise from using the trail. We cannot guarantee the accuracy of maps or completeness of warnings about hazards that may exist. Portions of the trail are along roads or train tracks and involve crossing them. Users should pay attention to traffic and walk on the shoulder of roads facing traffic, not on the pavement, cross only at designated locations and use extreme care. Children and pets need to be closely monitored and under control. 0.7 Kiosk for start of MCC fitness trail. To right Extension (also known as the Reformatory of kiosk, head south on trail into woods. Branch), where Bay Circuit 0.8 Cross MCC south entrance road, right for 150 marking picks up again. ft along grassed shoulder, and left into the 3.0 The dedicated BCT route turns right onto woods. Springs Rd sidewalk to jct of Springs Rd and Map 6 -Billerica, Bedford, Acton, Carlisle, 1.0 Cross Springs Rd into Governor Winthrop Hillside Ave. Use cross walk to continue Concord - BAY CIRCUIT TRAIL route Conservation Area and follow paths north of south on Springs Rd using sidewalk. This wetlands and woodlands. (as shown on map 6 dated July 2017) stretch of the BCT passes period homes and 1.4 Left onto Narrow Gauge Rail Trail to (text updated July 2017) the Old Burying Ground of the Bedford Sweetwater Ave. Historic District. 3.4 Reach Bedford Center at jct of Springs Rd The BCT often follows pre-existing local trails; L N42 30.889 W71 16.554 BCT-specific blazing is a work in progress and and Great Rd (Rtes 4/225). -

The Cloudsplitter Is Published Quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and Is Distributed to the Membership

The Cloudsplitter Vol. 79 No. 1 January-March 2016 published by the ALBANY CHAPTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB The Cloudsplitter is published quarterly by the Albany Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club and is distributed to the membership. All issues (January, April, July, and October) feature activities schedules, trip reports, and other articles of interest to the outdoor enthusiast. All outings should now be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org . Echoes should be entered on the web site www.adk-albany.org with your login information. The Albany Chapter may be Please send your address and For Club orders & membership For Cloudsplitter related issues, reached at: phone number changes to: call (800) 395-8080 or contact the Editor at: Albany Chapter ADK Adirondack Mountain Club e-mail: [email protected] The Cloudsplitter Empire State Plaza 814 Goggins Road home page: www.adk.org c/o Karen Ross P.O. Box 2116 Lake George, NY 12845-4117 7 Bird Road Albany, NY 12220 phone: (518) 668-4447 Lebanon Spgs., NY 12125 home page: fax: (518) 668-3746 e-mail: [email protected] www.adk-albany.org Submission deadline for the next issue of The Cloudsplitter is February 15, 2016 and will be for the months of April, May, and June, 2016. Many thanks to Gail Carr for her cover sketch of winter snows on the Mohawk River. January 6, February 3, March 2 (1st Wednesdays) Business Meeting of Chapter Officers and Committees 6:00 p.m. at Little’s Lake in Menands Chapter members are encouraged to attend - please call Tom Hart at 229-5627 Chapter Meetings are held at the West Albany Fire House (Station #1), 113 Sand Creek Road, Albany. -

3" L- Massachusetts

$outheastotn Breeze October/November/December 1997 :: :;b 3" l- Massachusetts The Nominating Committee will the Chapter's Annual Meeting. Together, present the following slate of Nominees the 13 of them are the Executive Board at the Annual Meeting on November 1. that run the Chapter. According to our Chapter's By-Laws; the Our Chapter's Standing Operating Executive Board shall be chosen by Bal- Rules speci$ that Committee Vice-Chairs lot, provided however, that should there are approved at the first Executive Board be but one nominee for an office, elec- meeting following the Annual Meeting. tion may be by voice vote. Executive Board meetings are held the Additional nominations may be made fourth Tuesday of the month at Bourne in writing by any ten members, who shall Community Building starting at 7:00 p.v. specifu their candidate and the office for which they nominate. Such nominations Annual Meeting shall be placed in the hands ofthe Chair- The Annual Meeting is a full day. person of the Nominating Committee not There will be hiking and biking during the later than 2 I days prior to the date of the day. These activities are a good introduc- Annual Meeting. tion to the Southeastern Massachusetts Chapter/AMC. See page 7 for details 1998 Nominees The evening schedule starts with a So- Chapter Chair..........Louise Desrochers cial Hour where it expected 90-100 will Vice-Chair... ..Lou Sikorsky attend. Dress is casual. New members can Treasurer.........................Charles Farrell meet and talk with hiking, biking canoe- Secretary...... ...Linda Wells ing and skiing leaders about trips they The Southeastern Massachusetts Biking Chair................