Kathleen Morrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

Government of Karnataka Provisional Habitation Wise Neighbourhood Schools

Government of Karnataka O/o Commissioner for Public Instruction, Nrupatunga Road, Bangalore - 560001 RURAL Provisional Habitation wise Neighbourhood Schools - 2016 ( RURAL ) Habitation Name School Code Management Lowest Highest Entry type class class class Habitation code / Ward code School Name Medium Sl.No. District : Bellary Block : BELLARY WEST Habitation : --- 29120114024 Pvt Unaided 1 10 Class 1 HPS ST. JOSEPH ENG.MD. (W) 19 - English 1 Habitation : BADANAHATTI---29120100501 29120100501 29120100501 Govt. 1 10 Class 1 BADANAHATTI GHPS & GHS BADANAHATTI 05 - Kannada 2 29120100501 29120100502 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 BADANAHATTI GLPS VALMIKI NAGARA BADANAHATTI 05 - Kannada 3 29120100501 29120100503 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 BADANAHATTI GLPS PANDURANGA NAGARA BADANAHATTI 05 - Kannada 4 29120100501 29120100504 Pvt Unaided 1 10 LKG BADANAHATTI SHREE NANDI RESIDENTIAL BADANAHATTI 19 - English 5 29120100501 29120100505 Pvt Unaided 1 5 Class 1 BADANAHATTI LPS VIDYAHARNA BADANAHATTI 05 - Kannada 6 29120100501 29120100508 Pvt Unaided 1 10 Class 1 BADANAHATTI SHREE NANDI RESIDENTIAL PUBLIC SCHOOL (ICSE) 19 - English 7 BADANAHATTI Habitation : BELAGAL---29120100801 29120100801 29120100801 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 BELAGAL GHPS BELAGAL 05 - Kannada 8 29120100801 29120100804 Pvt Unaided 1 5 Class 1 BELAGAL LPS SRI SADGURU B.BELAGAL 05 - Kannada 9 29120100801 29120100805 Pvt Unaided 1 10 Class 1 BELAGAL NANDI INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL B.BELAGAL 19 - English 10 29120100801 29120100806 Pvt Unaided 1 6 Class 1 BELAGAL LPS AKSHARA GANGOTHRI 05 - Kannada 11 Habitation : BELAGAL THANDA---29120100802 29120100802 29120100802 Govt. 1 8 Class 1 BELAGAL THANDA GHPS BELAGAL THANDA 05 - Kannada 12 Habitation : CHITIGINAHALU---29120102201 29120102201 29120102201 Govt. 1 5 Class 1 CHITIGINAHALU GLPS CHITIGINAHAL 05 - Kannada 13 Habitation : YEMMIGANUR---29120102601 29120102601 29120102601 Govt. -

Environmental Impact Assessment

Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 43253-026 November 2019 India: Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program – Project 2 Vijayanagara Channels Main Report Prepared by Project Management Unit, Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program Karnataka Neeravari Nigam Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank. This is an updated version of the draft originally posted in June 2019 available on https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/ind-43253-026-eia-0 This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. KARNATAKA NEERAVARI NIGAM LTD Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program ADB LOAN No. 3172-IND VIJAYANAGARA CHANNELS FEASIBILITY STUDY REPORT Volume 2a: Environmental Impact Assessment Project Management Unit, KISWRMIP Project Support Consultant SMEC International Pty. Ltd. Australia in association with SMEC (India) Pvt. Ltd. Final Revision: 16 September 2019 VNC Feasibility Study Report Volume -

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST Population % 21.10 18.41 23.89 21.81 16.45 12.74 27.61 7.49 29.85

POPULATION PROFILE OF BELLARY Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Bellary 2452595 517409 21.10 451406 18.41 2 Bellary 1532356 366016 23.89 334131 21.81 3 Bellary 920239 151393 16.45 117275 12.74 4 Hadagalli 195219 53893 27.61 14620 7.49 5 Hadagalli 167252 49925 29.85 12917 7.72 6 Hadagalli 27967 3968 14.19 1703 6.09 7 Hirabannimatti 2660 295 11.09 296 11.13 8 Byalhunsi 1139 255 22.39 37 3.25 9 Makarabbi 1827 319 17.46 182 9.96 10 Katebennuru 4799 400 8.34 138 2.88 11 Thumbinakeri 1521 1186 77.98 67 4.40 12 Hirehadagalli 8254 1370 16.60 807 9.78 13 Manihalli 136 0 0.00 51 37.50 14 Veerapura 1018 97 9.53 471 46.27 15 Budanur 1895 158 8.34 434 22.90 16 Holalu 9823 1475 15.02 767 7.81 17 Mylar 4110 729 17.74 265 6.45 18 Dombrahalli 1146 738 64.40 42 3.66 19 Dasanahalli 2088 179 8.57 341 16.33 20 Pothalakatti 0 0 0.00 0 0.00 21 Hyarada 4126 264 6.40 444 10.76 22 Kuravathi 4294 1201 27.97 212 4.94 23 Harivi Basapura 638 1 0.16 0 0.00 24 Harivi 2922 309 10.57 132 4.52 25 Beerabbi 2124 397 18.69 69 3.25 26 Kotihal 204 117 57.35 53 25.98 27 Angoor 2265 1209 53.38 197 8.70 28 Magala 5755 1063 18.47 554 9.63 29 Rangapura 12 0 0.00 0 0.00 30 Thimalapura 2315 724 31.27 178 7.69 31 Nowli 2956 956 32.34 562 19.01 32 Kotanakal 1252 231 18.45 168 13.42 33 Kombli 3268 338 10.34 684 20.93 34 Sovinahalli 3987 2030 50.92 301 7.55 35 Hakandi 3157 1395 44.19 237 7.51 36 Kalvi West 6626 5272 79.57 51 0.77 37 Koilaragatti 1813 984 54.27 223 12.30 38 Dasarahalli 2271 2243 98.77 1 0.04 39 Halathimalapura -

District Taluk Gram Panchayat Year Work Name Type of Building

Estimated Expenditure For District Taluk Gram Panchayat Year Work Name Type Of Building Expenditure Work status Amount SC/ST Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 Admistravite Expenditure other works 20000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 purchase playing materils & school furnitures School Compound and Buildings20000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 constrcuted cook room for aganavadi Kitchen Room 25000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 purchase school furnitures School Compound and Buildings25000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 purchase school furnitures School Compound and Buildings25000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 purchase school furnitures School Compound and Buildings25000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 constrcuted ladies toilet Construction of Toilet 100000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 providing c.c road from Hampanna house to Antapura road CC Road 124400 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 providing water facility to janatha khalony Drinking Water Supply 159000 0 0 Not Started Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 repair the panchyath room Repair Works 25000 25000 0 Completed Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 constrcuted drinage in harijana kholony Drainage 120000 92000 0 Completed Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 constrcuted school kampound School Compound and Buildings100000 100000 0 Completed Bellary Sandur Anthapura 2007-08 providing c.c.road from Harijana Shankarappa to khali house CC Road 125000 125000 -

Preliminary Observations on Odonata Fauna of Daroji Sloth Bear Sanctuary, Ballari District, North Karnataka (India)

Biodiversity Journal , 2017, 8 (4): 875–880 Preliminary observations on Odonata fauna of Daroji Sloth Bear Sanctuary, Ballari District, North Karnataka (India) Harisha M. Nijjavalli * & Basaling B. Hosetti Department of Post Graduate Studies and Research in Wildlife and Management, Kuvempu University, Jnana Sahyadri, Shanka - raghatta-577451, Shimoga, Karnataka, India *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The preliminary study was conducted from February 2011 to January 2012 at Daroji Sloth Bear Sanctuary, Hosept. The study revealed the occurrence of a total of 22 species of Odonates in 19 genera belonging to 5 families from the study area. Among them the order Anisoptera which includes dragonflies was predominated with 17 (76%) species, followed by the order Zygoptera which includes damselflies with 5 (24%) species. The family Libel - lulidae was found to be the most dominant by 13 species with high percentage composition i.e., 76%, followed by the family Coenagrionidae by 3 species with 40% of total odonates species recorded from the study area. The status based on the frequency of occurrence of shows that 8 (36%) were common, 5 (23%) were very common, 3 (14%) were occasional, 4 (18%) were rare and 2 (9%) were very rare. The study highlights the importance and also provides the baseline information on status and composition of Odonates at Daroji Sloth Bear Sanctuary, Ballari District of North Karnataka for research on their biology and the conservation. KEY WORDS Dragonflies; Damselflies; Odonates; Zygoptera; Anisoptera; Deccan Plateau. Received 23.09.2017; accepted 30.10.2017; printed 30.12.2017 INTRODUCTION ideal models for the investigation of the impact of environmental warming and climate change due It is generally difficult to evaluate invertebrate to their tropical evolutionary history and adapta - faunal diversity as they are often small, cryptic, tions to temperate climates (Nesemann et al., and seasonal, making even Red List assessments 2011). -

Independent Auditors' Report

INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT To The Members of JSW Realty & Infrastructure Private Limited, Report on the Audit of the Financial Statements 1. Opinion We have audited the accompanying financial statements of JSW Realty & Infrastructure Private Limited (“the Company”), (prepared for the purpose of consolidation with JSW Steel Ltd, the holding company under Ind AS), which comprises the Balance Sheet as at 31st March, 2021, the Statement of Profit and Loss (including other comprehensive income), Statement of Changes in Equity, the Cash Flow Statement for year then ended, and notes to the financial statements including a summary of Significant Accounting Policies and other explanatory information. In our opinion and to the best of our information and according to the explanations given to us, the aforesaid financial statements give the information required by the Act in the manner so required and give a true and fair view in conformity with the accounting principles generally accepted in India, of the state of affairs of the company as at March 31, 2021, its profit, changes in equity and its cash flows for the year ended on that date. 2. Basis for Opinion We conducted our audit in accordance with the Standards on Auditing (SAs) specified under section 143(10) of the Companies Act, 2013. Our responsibilities under those standards are further described in the Auditor’s Responsibilities for the Audit of the Financial Statements section of our report. We are independent of the Company in accordance with the Code of Ethics issued by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India together with the ethical requirements that are relevant to our audit of the financial statements under the provisions of the Companies Act, 2013 and the Rules there under, and we have fulfilled our other ethical responsibilities in accordance with these requirements and the Code of Ethics. -

Sub Centre List As Per HMIS SR

Sub Centre list as per HMIS SR. DISTRICT NAME SUB DISTRICT FACILITY NAME NO. 1 Bagalkote Badami ADAGAL 2 Bagalkote Badami AGASANAKOPPA 3 Bagalkote Badami ANAVALA 4 Bagalkote Badami BELUR 5 Bagalkote Badami CHOLACHAGUDDA 6 Bagalkote Badami GOVANAKOPPA 7 Bagalkote Badami HALADURA 8 Bagalkote Badami HALAKURKI 9 Bagalkote Badami HALIGERI 10 Bagalkote Badami HANAPUR SP 11 Bagalkote Badami HANGARAGI 12 Bagalkote Badami HANSANUR 13 Bagalkote Badami HEBBALLI 14 Bagalkote Badami HOOLAGERI 15 Bagalkote Badami HOSAKOTI 16 Bagalkote Badami HOSUR 17 Bagalkote Badami JALAGERI 18 Bagalkote Badami JALIHALA 19 Bagalkote Badami KAGALGOMBA 20 Bagalkote Badami KAKNUR 21 Bagalkote Badami KARADIGUDDA 22 Bagalkote Badami KATAGERI 23 Bagalkote Badami KATARAKI 24 Bagalkote Badami KELAVADI 25 Bagalkote Badami KERUR-A 26 Bagalkote Badami KERUR-B 27 Bagalkote Badami KOTIKAL 28 Bagalkote Badami KULAGERICROSS 29 Bagalkote Badami KUTAKANAKERI 30 Bagalkote Badami LAYADAGUNDI 31 Bagalkote Badami MAMATGERI 32 Bagalkote Badami MUSTIGERI 33 Bagalkote Badami MUTTALAGERI 34 Bagalkote Badami NANDIKESHWAR 35 Bagalkote Badami NARASAPURA 36 Bagalkote Badami NILAGUND 37 Bagalkote Badami NIRALAKERI 38 Bagalkote Badami PATTADKALL - A 39 Bagalkote Badami PATTADKALL - B 40 Bagalkote Badami SHIRABADAGI 41 Bagalkote Badami SULLA 42 Bagalkote Badami TOGUNSHI 43 Bagalkote Badami YANDIGERI 44 Bagalkote Badami YANKANCHI 45 Bagalkote Badami YARGOPPA SB 46 Bagalkote Bagalkot BENAKATTI 47 Bagalkote Bagalkot BENNUR Sub Centre list as per HMIS SR. DISTRICT NAME SUB DISTRICT FACILITY NAME NO. -

04-12-2020 Sr. No. Case Number T

SENIOR CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC COURT, KUDLIGI K.A.Nagesha SR CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC Cause List Date: 04-12-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate AFTERNOON SESSION 2:45 PM -5:00 PM 1 O.S. 63/2015 Kumari Gouthami minor reprtd M Basavaraju (ARGUMENTS) by their guardian next frd IA/1/2015 Balarama So Eranna IA/2/2015 Vs Smt Parvathamma wife of late Anjinappa 2 O.S. 67/2015 Smt K Honnuramma wife of Late Thippeswamy K (ARGUMENTS) Mallappa Vs K Komarappa son of Late Lakshmappa 3 O.S. 71/2015 Ananda Chirania A Vijayakumar (EVIDENCE-C) Vs IA/1/2015 Parvathamma Wo Late Adeppa and others 4 O.S. 91/2015 H T Nagareddy So late H N Jathappa adv (EVIDENCE-C) Thimappa IA/1/2015 Vs IA/2/2015 Lakshmamma Wo Late Somanna 5 O.S. 92/2015 H T Nagareddy son of late N Jathappa adv (EVIDENCE-C) Hosakote Thimmappa IA/1/2015 Vs IA/2/2015 Devamma Wo Ramanjini 6 R.A. 1/2016 Smt Gangamma wife of Late N D S Badarinath (ARGUMENTS) Rudrappa IA/1/2016 Vs K S L swamy son of K Sore Lingappa 7 O.S. 40/2016 Smt. Ranjitha Wo. Jagadeeesh H. Nagaraja (ARGUMENTS) Vs IA/1/2016 Shivanand So. late Rudragouuda 8 O.S. 101/2016 V Babaiah son of Daroji vaddara Banakar (EVIDENCE-C) Thimmappa Manjunath IA/1/2016 Vs Daroji Vaddara Thimmappa son of late Vaddara Thimmappa 9 O.S. 106/2016 Kotagi Malappa Son of Late K (EVIDENCE-C) Kotagi Nagappa NAGABHUSHANA Vs RAO D.Manjunath Son of Bhimasaen Rao Deshpande 10 O.S. -

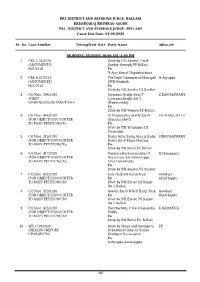

Prl District and Sessions Judge, Ballari Krishnaraj Bhimrao Asode Prl

PRL DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE, BALLARI KRISHNARAJ BHIMRAO ASODE PRL. DISTRICT AND SESSIONS JUDGE, BELLARY Cause List Date: 01-09-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate MORNING SESSION 10:00 AM -1:00 PM 1 CRL.A 38/2016 State by CPI Sandur Circle (ARGUMENTS) Sandur through PP Ballari IA/1/2016 Vs N Ajay Son of Nagabhushana 2 CRL.A 37/2018 The Divnl Commercial Manager N.Ayyappa (ARGUMENTS) SWR Hubballi IA/1/2018 Vs State by PSI Sandur PS Sandur 3 Crl.Misc. 394/2020 Jayarama Reddy Alias T S.RANGASWAMY (FIRST Jayarama Reddy S/o T HEARING/COGNIZANCE(CR)) Bheemareddy Vs State by PSI Women PS Ballari 4 Crl.Misc. 408/2020 M Manjunatha Shetty S/o M PH MANJUNATH (FOR OBJECTION/COUNTER Ayyanna Shetty TO MAIN PETITION(CR)) Vs State by PSI Siruguppa PS Siruguppa 5 Crl.Misc. 415/2020 Basha Alias Sadiq Alias S Sadiq S.RANGASWAMY (FOR OBJECTION/COUNTER Basha S/o S Khaja Hussain TO MAIN PETITION(CR)) Vs State by PSI Rural PS Ballari 6 Crl.Misc. 417/2020 Gurikara Basavaraja Alias G H Hulugappa (FOR OBJECTION/COUNTER Basavaraja S/o Hanumappa TO MAIN PETITION(CR)) Alias Hanumayya Vs State by PSI Sandur PS Sandur 7 Crl.Misc. 422/2020 Kala Naik S/o Kisan Naik Gowdara (FOR OBJECTION/COUNTER Vs Shanthappa TO MAIN PETITION(CR)) State by PSI Excise PS Range No 1 Ballari 8 Crl.Misc. 423/2020 Geetha Bai D W/o D Balaji Naik Gowdara (FOR OBJECTION/COUNTER Vs Shanthappa TO MAIN PETITION(CR)) State by PSI Excise PS Range No 1 Ballari 9 Crl.Misc. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

25-11-2020 Sr. No. Case

CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC COURT JUDGE, SANDUR MANJUNATHA R CIVIL JUDGE AND JMFC , SANDUR Cause List Date: 25-11-2020 Sr. No. Case Number Timing/Next Date Party Name Advocate AFTERNOON SESSION 2:45 PM -5:00 PM 1 O.S. 1/2015 THE NMDC LTD BY T.M SHIVA KUMAR (EVIDENCE-C) EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR IA/2/2015 Vs IA/1/2015 NANDI THIPPESWAMY SON OF KOMARAPPA 2 O.S. 3/2015 TALAWAR NAGARAJA SON OF A VIJAYA KUMAR (EVIDENCE-C) LATE TALAWAR HANUMANTHAPPA Vs BALEGAR MUDIMALLAPPA SON OF LATE BALEGAR HEMAPPA 3 O.S. 4/2015 S BASAVARAJAIAH SON OF M LOKESH ADV (EVIDENCE ON DEFENCE(CR)) LATE S PORAIAH IA/3/2015 Vs IA/2/2015 BHEEMASENA P NATEKAR IA/1/2015 SON OF PEERAPPA NATENKAR 4 O.S. 47/2016 Darimane Anjinappa So Late GOWLERU (EVIDENCE-C) KOmarappa, 55, Ro D Mallapur MALLIKARJUNA IA/2/2016 village sandur IA/1/2016 Vs Harijana Mudi rangappa, So Late Mallappa, 60 years 5 O.S. 94/2016 Smt C Radhamadhavi by her M Arunodaya Rao (EVIDENCE-C) power of attornery holder C IA/2/2016 Hanumanthappa, RO Choranur IA/1/2016 village, Sandur Tq Vs T Anjinappa SO Late T Hulukuntappa, RO Choranur village, Sandur Taluk, Ballari Dist 6 O.S. 133/2016 Sirigeri Mallamma W/o Late A VIJAYA KUMAR (EVIDENCE-C) Nagana Gouda, Vs Basavaraj S/o Sirigeri Rudragouda 7 O.S. 13/2017 Bhuvaneshwari D/o Dodda K.M. Sadashivayya (EVIDENCE-C) Veerabhadra Gouda W/o M Advt Hospet IA/2/2017 Veerabhadra Gouda IA/1/2017 Vs Mallikarjuna S/o Veerbhadra Gouda 8 O.S.