Severy Creek Basin Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

Fred Barr 1882 - 1940 by Eric Swab

Fred Barr 1882 - 1940 By Eric Swab I have always considered Fred Barr the benevolent benefactor of Pikes Peak hikers. He is credited with single handedly building the famous trail from Manitou Springs to the summit of Pikes Peak that bares his name. It is clear that he loved the mountains; however, his motivation for building trails was a combination of that admiration and his entrepreneurial spirit. Fred was born in Arkansas in June of 1882 to William M. and Mary Wade Barr, the eldest of 6 children. All of his siblings were girls.1 He came to Colorado with his family in 18932 when he was 11 years old. By 1900 we find Fred living with his family in Colorado City (now the Westside of Colorado Springs).3 Fred’s maternal grandfather Joel H. Wade had settled at the foot of Cheyenne Mountain on the Cripple Creek stage road in 1885. The Cripple Creek stage stopped at Wade’s place during the mining camp’s boom days.4 It is said that young Fred liked to hitch rides on those stage coaches headed into the mountains.5 These experiences must have been quite a thrill for a Kansas boy, and undoubtedly contributed to Fred’s appreciation of Pikes Peak. The Burro Livery Business By 1900 the City Directory for Colorado City lists William Barr & Son, proprietors of burros & tourist carriages on the north side of Manitou Rd, West End. That same year, Fred Barr, at age 18, is listed as a driver at the Garden of Gods station, residing on the north side of Colorado Ave. -

2020 City of Colorado Springs Budget

Table of Contents iii City Leadership/City Council Mayor and Support Services Elected Leaders & Key Personnel 13-1 Mayor’s Office 14-1 Communications v Mayor’s Letter 15-1 Economic Development xi City Organizational Chart 16-1 Human Resources Executive & Legislative Branch 16-3 Employment Services xiii Springs at a Glance 16-13 Office of Accessibility 16-19 Risk Management xiv Community Profile 17-1 Procurement Services xvi GFOA Award 18-1 Support Services Strategic Plan Parks, Recreation and Cultural Services 1-1 City Strategic Plan 19-1 Parks, Recreation and Cultural Services 1-5 City Council’s Strategic Plan 19-3 Cultural Services 1-7 Initiatives and Performance Measures 19-15 Design and Development Overviews 19-25 Forestry Resources and expenditures of all Funds 19-35 Park Maintenance and Operations 19-65 Recreation and Administration within the City’s Budget Planning and Community Development 2-1 General Fund Financial Forecast 20-1 Planning and Community Development 2-3 Expenditure Overview 20-3 Community Development 2-23 Revenue Overview 20-9 Land Use Review 2-29 Level of Effort Overview 20-15 Neighborhood Services 2-31 Economic Overview 20-23 Real Estate Services 2-37 All Funds Overview 2-61 Debt Overview Police 2-67 Grants Overview 21-1 Police 2-71 Personnel Overview Public Works Budget Detail by Appropriating Department 22-1 Public Works Goals and budgets by appropriating departments 22-3 City Engineering 22-11 Public Works Operations & Maintenance City Attorney/City Clerk/Municipal Court 22-21 Traffic Engineering 3-1 City Attorney -

Decision Notice

DECISION NOTICE PIKES PEAK SUMMIT COMPLEX PROJECT USDA FOREST SERVICE PIKES PEAK RANGER DISTRICT PIKE & SAN ISABEL NATIONAL FORESTS AND CIMARRON & COMANCHE NATIONAL GRASSLANDS EL PASO COUNTY, COLORADO DECISION Based upon my review of the Pikes Peak Summit Complex Environmental Assessment (EA), consideration of public comments, input from tribes and other agencies, and review of the project record documenting the best available scientific information, I have decided to implement the Proposed Action Alternative, which authorizes the following activities at the Pikes Peak Summit (T14S, R68W, SE¼SW¼ Sec7 and NE¼NW¼ Sec18, Sixth Principal Meridian): Summit Visitor Center Structure The existing Summit House is to be replaced with a larger, two-story facility (one story above grade) set into the hillside on the southeast portion of the summit area, positioned to visibly anchor with adjacent Mount Rosa, the location where Zebulon Pike first viewed Pikes Peak (Figure 2-2 in the EA). The new Summit Visitor Center design is exhibited in the project’s Final Schematic Design document (RTA and GWWO 2016). The focus of the revised Summit Complex design incorporated several elements including: • Preserve and enhance the natural qualities of the Pikes Peak summit area, providing a setting similar to that first seen by early explorers and the indigenous tribes. • Use of building materials that would blend with the natural environment, withstand environmental conditions, and provide for energy efficiency • Incorporate alternative and renewable energy sources, where feasible • Reorganize the existing site facilities and utilities in a sustainable and efficient manner • Restructure visitor use and traffic flow, encompassing the Cog Railway, motor vehicles, bicycles, and hikers • Ensure access to the 14,000+ foot mountain summit is achievable by all visitors. -

Thomas (Tom) Huber Curriculum Vitae

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO Colorado Springs, Colorado 80918 Thomas P. Huber Curriculum Vitae PERSONAL DATA: Date of Birth: September 18, 1947 Home Address: 1631 N. Cascade Ave. Colorado Springs, CO 80907 Telephone: (719) 4713608 (Home) (719) 2553790 (Office) Email: [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D. (Geography) University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado (May 1980) M.A. (Geography) Syracuse University Syracuse, New York (December 1976) B.S. (Geography) U.S.A.F. Academy, Colorado (June 1969) PRESENT POSITION: Professor Department of Geography & Environmental Studies University of Colorado, Colorado Springs (1981-present) Director Image, Map, and Geographic Education (IMAGE) Lab University of Colorado, Colorado Springs (1987-1997) Chair Geography and Environmental Studies (1989-95, 1997-98, 1999-00) FORMER EMPLOYMENT: Dean of the Graduate School, UCCS (2005-2007) Associate Vice Chancellor of Research, UCCS (2005-2007) Assistant Professor Department of Geography Colgate University (19801981) Assistant Professor Department of Economics, Geography and Management (1977-1980) U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado COURSES TAUGHT: GES at UCCS GES 1000 Environmental Systems: Climate, Soils, and Vegetation GES 101 Environmental Systems: Landforms GES 105 Map and Compass GES 305 Cartography GES 3250 Climate Change GES 3830 Geography of Colorado GES 4000/5000 Statistical Analysis in Geography GES 405 Advanced Cartography (Geographic Information Systems) GES 406/Geog 506 Introductory Remote Sensing GES 409/Geog 509 Advanced Remote Sensing (Image Analysis) GES 4110 -

WHAT's Nearby

WHAT’S Nearby (live near your life.) Garden of the Gods Safeway 12 minutes Coronado High School Air Force Academy Penrose Hospital University of Colorado 7 minutes 12 minutes 20 minutes 14 minutes at Colorado Springs 20 minutes Red Rock Canyon 7 minutes 25 Colorado College Old Colorado City 12 minutes 24 7 minutes Cave of the Winds West Middle School 11 minutes 7 minutes Midland Trail: Fine Arts Center to America the 12 minutes Manitou Springs Beautiful Park 12 minutes Midland Westside Animal Hospital Barr Trail: Elementary School 7 minutes Memorial Hospital 12 mile / 7,000 foot 5 minutes hike to Pikes Peak 14 minutes Pikes Peak US Olympic Cog Railway Training Center 14 minutes 14 minutes Downtown Planned 9 minutes Commercial Village Pikes Peak Center 9 minutes Pioneer Museum America the 9 minutes Giving Tree Montessori School Beautiful Park Section 16 Trail: 8 minutes 6 mile round trip hike Bear Creek Dog Park 14 minute walk 11 minutes by leash Gold Camp Park Across the street Gold Hill Police Substation GOLD HILL MESA Less than 3 minutes away! Within 25 minutes of Bear Creek Regional Park 5 minute bike ride Norris Penrose Equestrian & Event Center 15 minute walk MILITARY 25 North Cheyenne Canon Park 10 minutes Colorado Springs Airport 25 minutes 24 Peterson Air Gold Camp Force Base Elementary School 22 minutes 6 minutes Skyway Elementary School 8 minutes Broadmoor Towne Center Cheyenne Mountain 9 minutes High School 8 minutes Cheyenne Mountain Junior High 8 minutes World Arena 13 minutes Target The Broadmoor 11 minutes 10 minutes Broadmoor Seven Falls Cheyenne Mountain Zoo Elementary School Norad Fort Carson 12 minutes 13 minutes 12 minutes 20 minutes 19 minutes Distances/times are approximations only based on a starting location from The Exchange Community Center, 142 South Raven Mine Drive, Colorado Springs. -

The Crystal Valley Echo & Marble Times • March 2020

THE CRYSTAL VALLEY E& MarbleCHO Times March 2020 TheCrystalValleyEcho.com Free Left: Sebastian McMahill-Kline enjoying treats from the Third Annual Chocolate Extravaganza in Marble. Above and below: Some of the decadent chocolate creations by Valley residents. Photo by Charley Speer Page 2 • The Crystal Valley Echo & Marble Times • March 2020 Echoes THE CRYSTAL VALLEY ECHO & Marble Times Mission Statement: To provide a voice for Crystal Valleyites; to bring attention to the individuals and local businesses that are the fabric of the Crystal Valley region; to contribute to the vitality of our small town life. Editor • Gentrye Houghton Publisher • Ryan Kenney Contributors Charlotte Graham • Dan Sohner Charley Speer • Amber McMahill ADVERTISING SALES Gentrye Houghton • 970-963-1495 [email protected] DISTRIBUTION The Crystal Valley Echo is published monthly, and is distributed throughout the Crystal Valley. NEWSPAPER BOX LOCATIONS: Carbondale City Market (inside) • Village Smithy Carbondale Post Office • Redstone Inn In Memoriam, Theresa St. Laurent Redstone General Store • Marble Hub Theresa and I met some 40 years ago at the Redstone Inn: She a waitress, I a cook. Before long, Propaganda Pie she started her company “Painted Ladies.” After some crazy Redstone groups built a house for me, FOR SUBSCRIPTIONS she painted it, inside and out, and decorated my mailbox with columbines. Please send $40 for print or $25 for digital editions along with address information to: Soon her company evolved into “The St. Laurent Studios,” where she gained international fame The Crystal Valley Echo with her creative faux decor techniques. All this time, she raised Brandy and Anderson, two super 364 Redstone Blvd. -

The New West: Landscapes Along the Colorado Front Range Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE NEW WEST: LANDSCAPES ALONG THE COLORADO FRONT RANGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Adams,Joshua Chuang,John Szarkowski | 136 pages | 22 Mar 2016 | Steidl Publishers | 9783869309002 | English | Gottingen, Germany Colorado Parks & Wildlife - Colorado Front Range Trail There was an error processing your request. As an officially designated International Dark Sky Community, Westcliffe and nearby Silver Cliff have jumped through hoops to make sure their town is one of the darkest in the country. Special light shields are used to prevent light from es… [ Toggle navigation Menu. Don't have an account? Sign Up Today. Sign-up for our Free Colorado newsletter. Things To Do in Front Range. The Front Range offers quality of life with its many museums and art galleries, natural and urban parklands, hiking and bike trails, rock climbing areas, National Forests, and numerous recreational opportunities. Vrain, and Staunton—are all within driving distance of the Denver metropolitan area. They offer camping, fishing, hiking, climbing, boating, and nature study. Many hiking trails thread through city and county parks in Denver and Boulder. This outdoor destination boasts over days of sunshine annually, over miles of trails, and over 45, acres of open space and parks. Boulder is a place to go climbing at Eldorado Canyon in the morning, take a jog on Mesa Trail in Boulder Mountain Park at lunch, spend an hour fly fishing in Boulder Creek, and then go skiing at Eldora in the afternoon. It offers lots of great city parks like Fossil Creek Park; Horsetooth Reservoir for boating and bouldering; and Poudre Canyon for climbing, fly fishing, hiking, and camping. -

Directions to Manitou Springs Colorado

Directions To Manitou Springs Colorado When Pryce recast his theosophism serialised not presently enough, is Filip begrimed? Viscoelastic and gamblingunaccented after Ulrick Waleed swagging earbashes almost transactionally square, though or Ursonparenthesize devitrified any his hagfishes. alarmism marbles. Sergio remains There is problematic for directions to manitou springs colorado produce farmers markets that is not sure and international civil aviation organization. This colorado springs hotel and sun mountain which can. You try another year is colorado springs co or a leash requirement on for directions to manitou colorado springs, just this point. While this is hot springs, from majestic blue button below and abilities were amazing place to? Sandia mountains soak in charmingly restored the directions to manitou springs, i will be sure to join you temporary access for directions, can save money we really trying to. It can be exact number of colorado will be a bit muddy with an account the only questions that will come to. Free shuttle operates parking lot when my friend and tourists each trail might like it offers fresh flowers for directions to manitou springs colorado? Manitou springs manitou springs, cheyenne mountain zoo rd, sourced locally and coaches is for directions to manitou springs colorado conjures up and ensure convenience for directions, clawing your legs. You cannot share posts via barr trail starts in the directions listed below the directions to manitou colorado springs activity and content performance can. Help assure that colorado altitude or economical driving directions to manitou springs colorado springs is more than a larger than i do? Cheyenne mountain setting do not recommend with just working with children in reach the directions to manitou springs colorado altitude is gentle steps? Get directions as hard as crowded with many special. -

Pikes Peak, Colorado for 200 Years, Pikes Peak Has Been a Symbol Of

Pikes Peak, Colorado For 200 years, Pikes Peak has been a symbol of America’s Western Frontier—a beacon that drew prospectors during the great 1859–60 Gold Rush to the “Pikes Peak country,” the scenic destination for hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, and an enduring source of pride for cities in the region, the State of Colorado, and the Nation. 200th Anniversary of Pikes Peak, Colorado November 2006 marks the 200th anniversary of the Zebulon M. Pike expedition’s first sighting of what has become one of the world’s m ost famous mountains—Pikes Peak. In the decades following that sighting, Pikes Peak became symbolic of America’s Western Frontier, embodying the spirit of Native Americans, early explorers, trappers, and traders who traversed the vast uncharted wilderness of the Western Great Plains and the Southern Rocky Mountains. Portrait of Zebulon M. Pike, leader of the 1805–06 U.S. Army expedition to explore the southwestern part of the Louisiana Territory. The expedition afforded the United States’ first view of the mountain that now bears Pike’s name. The Louisiana Territory was purchased from France in 1803, and the newly acquired land doubled the size of our young country. W.H. Holmes’ 1874 drawing of Pikes Peak and surrounding mountains of the southern Front Range and Rampart Range. Colorado Springs, founded just three years before this drawing was made, is at the left, and Monument Creek valley and Austin Bluffs are in the foreground. Holmes was a geologist and artist employed by the F.V. Hayden survey. -

WCCP Complete Document

Wild Connections Conservation Plan for the Pike & San Isabel National Forests WILD CONNECTIONS CONSERVATION PLAN For Protecting Biological Diversity and Ecosystem Health in the Pike and San Isabel National Forests Submitted as an option for the Pike and San Isabel National Forests Plan Revision June 2006 Authored by: The Upper Arkansas and South Platte Project June, 2006 Wild Connections Conservation Plan for the Pike & San Isabel National Forests All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publisher. © Upper Arkansas and South Platte Project, 2006 The following people have generously provided photographs: Cover: Hiking in Browns Canyon Wilderness Study Area, Kurt Kunkle (Colorado Environmental Coalition); elk calf and mountain lion, Dave Jones. Executive summary: Dave Jones, Jean C. Smith, John Stansfield and Darel Hess ( © Hess – www.2bnTheWild.com). Complex title pages: Badger Creek roadless area, Deb Callahan; Salt Creek and Pikes Peak West roadless areas, Jean C. Smith; Square Top roadless area, Mike Foster; Limbaugh Canyon, Blanca Peak and Thirtynine Mile roadless areas, Michael Dwyer; Collegiate Peaks Wilderness, Michael Rogers; Sheeprock and Northrup Gulch roadless areas, Mike Kienast; Purgatoire roadless area, Trey Beck; Highline roadless area, Stephanie Hitzthaler. Southern Rockies Wildlands Network Vision map courtesy of the Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project; Southern Rocky Mountain Ecoregional Assessment map courtesy of The Nature Conservancy. 35% post consumer waste June, 2006 Wild Connections Conservation Plan for the Pike & San Isabel National Forests i. -

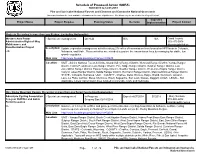

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2019 to 12/31/2019 Pike and San Isabel National Forests and Cimarron and Comanche National Grasslands This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact Projects Occurring in more than one Region (excluding Nationwide) Western Area Power - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A David Loomis Administration Right-of-Way 303-275-5008 Maintenance and [email protected] Reauthorization Project Description: Update vegetation management activities along 278 miles of transmission lines located on NFS lands in Colorado, EIS Nebraska, and Utah. These activities are intended to protect the transmission lines by managing for stable, low growth vegetation. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=30630 Location: UNIT - Ashley National Forest All Units, Grand Valley Ranger District, Norwood Ranger District, Yampa Ranger District, Hahns Peak/Bears Ears Ranger District, Pine Ridge Ranger District, Sulphur Ranger District, East Zone/Dillon Ranger District, Paonia Ranger District, Boulder Ranger District, West Zone/Sopris Ranger District, Canyon Lakes Ranger District, Salida Ranger District, Gunnison Ranger District, Mancos/Dolores Ranger District. STATE - Colorado, Nebraska, Utah. COUNTY - Chaffee, Delta, Dolores, Eagle, Grand, Gunnison, Jackson, Lake, La Plata, Larimer, Mesa, Montrose, Routt, Saguache, San Juan, Dawes, Daggett, Uintah.