Arxiv:1801.02717V1 [Math.DG]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CMI Summer Schools

CMI Summer Schools 2007 Homogeneous flows, moduli spaces, and arithmetic De Giorgi Center, Pisa 2006 Arithmetic Geometry The Clay Mathematics Institute has Mathematisches Institut, conducted a program of research summer schools Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen since 2000. Designed for graduate students and PhDs within five years of their degree, the aim of 2005 Ricci Flow, 3-manifolds, and Geometry the summer schools is to furnish a new generation MSRI, Berkeley of mathematicians with the knowledge and tools needed to work successfully in an active research CMI summer schools 2004 area. Three introductory courses, each three weeks Floer Homology, Gauge Theory, and in duration, make up the core of a typical summer Low-dimensional Topology school. These are followed by one week of more Rényi Institute, Budapest advanced minicourses and individual talks. Size is limited to roughly 100 participants in order to 2003 Harmonic Analysis, Trace Formula, promote interaction and contact. Venues change and Shimura Varieties from year to year, and have ranged from Cambridge, Fields Institute, Toronto Massachusetts to Pisa, Italy. The lectures from each school are published in the CMI–AMS proceedings 2002 Geometry and String Theory series, usually within two years’ time. Newton Institute, Cambridge UK Summer Schools 2001 www.claymath.org/programs/summer_school Minimal surfaces MSRI, Berkeley Summer School Proceedings www.claymath.org/publications 2000 Mirror Symmetry Pine Manor College, Boston 2006 Arithmetic Geometry Summer School in Göttingen techniques are drawn from the theory of elliptic The 2006 summer school program will introduce curves, including modular curves and their para- participants to modern techniques and outstanding metrizations, Heegner points, and heights. -

Convergence of Complete Ricci-Flat Manifolds Jiewon Park

Convergence of Complete Ricci-flat Manifolds by Jiewon Park Submitted to the Department of Mathematics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY May 2020 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2020. All rights reserved. Author . Department of Mathematics April 17, 2020 Certified by. Tobias Holck Colding Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Wei Zhang Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Theses 2 Convergence of Complete Ricci-flat Manifolds by Jiewon Park Submitted to the Department of Mathematics on April 17, 2020, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics Abstract This thesis is focused on the convergence at infinity of complete Ricci flat manifolds. In the first part of this thesis, we will give a natural way to identify between two scales, potentially arbitrarily far apart, in the case when a tangent cone at infinity has smooth cross section. The identification map is given as the gradient flow of a solution to an elliptic equation. We use an estimate of Colding-Minicozzi of a functional that measures the distance to the tangent cone. In the second part of this thesis, we prove a matrix Harnack inequality for the Laplace equation on manifolds with suitable curvature and volume growth assumptions, which is a pointwise estimate for the integrand of the aforementioned functional. This result provides an elliptic analogue of matrix Harnack inequalities for the heat equation or geometric flows. Thesis Supervisor: Tobias Holck Colding Title: Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor 3 4 Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank my advisor Tobias Colding for his continuous guidance and encouragement, and for suggesting problems to work on. -

Notices of the AMS 595 Mathematics People NEWS

NEWS Mathematics People contrast electrical impedance Takeda Awarded 2017–2018 tomography, as well as model Centennial Fellowship reduction techniques for para- bolic and hyperbolic partial The AMS has awarded its Cen- differential equations.” tennial Fellowship for 2017– Borcea received her PhD 2018 to Shuichiro Takeda. from Stanford University and Takeda’s research focuses on has since spent time at the Cal- automorphic forms and rep- ifornia Institute of Technology, resentations of p-adic groups, Rice University, the Mathemati- especially from the point of Liliana Borcea cal Sciences Research Institute, view of the Langlands program. Stanford University, and the He will use the Centennial Fel- École Normale Supérieure, Paris. Currently Peter Field lowship to visit the National Collegiate Professor of Mathematics at Michigan, she is Shuichiro Takeda University of Singapore and deeply involved in service to the applied and computa- work with Wee Teck Gan dur- tional mathematics community, in particular on editorial ing the academic year 2017–2018. boards and as an elected member of the SIAM Council. Takeda obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical The Sonia Kovalevsky Lectureship honors significant engineering from Tokyo University of Science, master's de- contributions by women to applied or computational grees in philosophy and mathematics from San Francisco mathematics. State University, and a PhD in 2006 from the University —From an AWM announcement of Pennsylvania. After postdoctoral positions at the Uni- versity of California at San Diego, Ben-Gurion University in Israel, and Purdue University, since 2011 he has been Pardon Receives Waterman assistant and now associate professor at the University of Missouri at Columbia. -

2.1 Harmonic Map Heat Flow from a Circle

Self-shrinkers of Mean Curvature Flow and Harmonic Map Heat Flow with Rough Boundary Data by 0 TECHF 2L ' Lu Wang SEP 0 2 20 Bachelor of Science, Peking University, July 2006 LIRARIS Submitted to the Department of Mathematics ARCHNES in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2011 @ Lu Wang, MMXI. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. A uthor .......... ........................................... Department of Mathematics Lr'\ '~I April 19, 2011 Certified by -- ------ - ........................ Tobias H. Colding Levinson Professor of Mathematics Thesis Supervisor Accepted by 37 Bjorn Poonen Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students 2 Self-shrinkers of Mean Curvature Flow and Harmonic Map Heat Flow with Rough Boundary Data by Lu Wang Submitted to the Department of Mathematics on April 19, 2011, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract In this thesis, first, joint with Longzhi Lin, we establish estimates for the harmonic map heat flow from the unit circle into a closed manifold, and use it to construct sweepouts with the following good property: each curve in the tightened sweepout, whose energy is close to the maximal energy of curves in the sweepout, is itself close to a closed geodesic. Second, we prove the uniqueness for energy decreasing weak solutions of the har- monic map heat flow from the unit open disk into a closed manifold, given any H' initial data and boundary data, which is the restriction of the initial data on the boundary of the disk. -

Mathematician Unleashes 'A Wave of New Results' in Geometric Analysis 4 June 2014, by Helen Knight

Mathematician unleashes 'a wave of new results' in geometric analysis 4 June 2014, by Helen Knight would form with that shape as its boundary. Although intuition would tell you that it should do this, there is no way to physically test the infinite number of possible variations that could be made to the shape of the wire in order to provide mathematical proof, Minicozzi says. A top geometric analyst Answering Plateau's question—and addressing subsequent conjectures on the properties of complex minimal surfaces—has kept mathematicians busy ever since. The most notable of these researchers in recent years have been Minicozzi and his colleague Tobias Colding, the MIT mathematics professor William Minicozzi in his Cecil and Ida Green Distinguished Professor of office at Building E17. Minicozzi studies the theory of Mathematics at MIT. Together, Minicozzi and surface tension in solutions. Credit: Dominick Reuter Colding are widely considered to be the world's leading geometric analysts of their generation. In 2004 the duo jointly published a series of papers It's something children do every day when blowing in the Annals of Mathematics that resolved a bubbles: Stick a circular wire in a pot of soapy number of longstanding conjectures in the field; this water, pull it out, and behold the film forming earned them the prestigious Oswald Veblen Prize across it. in Geometry. But it's not only children who are amused by this Of particular interest to Minicozzi and Colding was phenomenon—which has also kept mathematicians whether it is possible to describe what all minimal occupied since the 18th century, says William surfaces look like. -

Mathematics Opportunities

Mathematics Opportunities will be published by the American Mathematical Society, NSF Integrative Graduate by the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, or jointly by the American Statistical Association and the Education and Research Institute of Mathematical Statistics. Training Support is provided for about thirty participants at each conference, and the conference organizer invites The Integrative Graduate Education and Research Training both established researchers and interested newcomers, (IGERT) program was initiated by the National Science including postdoctoral fellows and graduate students, to Foundation (NSF) to meet the challenges of educating Ph.D. attend. scientists and engineers with the interdisciplinary back- The proposal due date is April 8, 2005. For further grounds and the technical, professional, and personal information on submitting a proposal, consult the CBMS skills needed for the career demands of the future. The website, http://www.cbms.org, or contact: Conference program is intended to catalyze a cultural change in grad- Board of the Mathematical Sciences, 1529 Eighteenth Street, uate education for students, faculty, and universities by NW, Washington, DC 20036; telephone: 202-293-1170; establishing innovative models for graduate education in fax: 202-293-3412; email: [email protected] a fertile environment for collaborative research that tran- or [email protected]. scends traditional disciplinary boundaries. It is also intended to facilitate greater diversity in student participation and —From a CBMS announcement to contribute to the development of a diverse, globally aware science and engineering workforce. Supported pro- jects must be based on a multidisciplinary research theme National Academies Research and administered by a diverse group of investigators from U.S. -

Jeff Cheeger

Progress in Mathematics Volume 297 Series Editors Hyman Bass Joseph Oesterlé Yuri Tschinkel Alan Weinstein Xianzhe Dai • Xiaochun Rong Editors Metric and Differential Geometry The Jeff Cheeger Anniversary Volume Editors Xianzhe Dai Xiaochun Rong Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics University of California Rutgers University Santa Barbara, New Jersey Piscataway, New Jersey USA USA ISBN 978-3-0348-0256-7 ISBN 978-3-0348-0257-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-0348-0257-4 Springer Basel Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2012939848 © Springer Basel 2012 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Permissions for use may be obtained through RightsLink at the Copyright Clearance Center. Violations are liable to prosecution under the respective Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. -

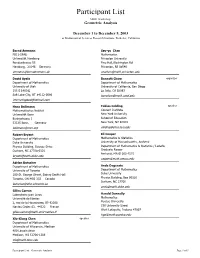

Participant List MSRI Workshop: Geometric Analysis

Participant List MSRI Workshop: Geometric Analysis December 1 to December 5, 2003 at Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, Berkeley, California Bernd Ammann Szu-yu Chen FB11-SPAD Mathematics Universität Hamburg Princeton University Bundesstrasse 55 Fine Hall,Washington Rd Hamburg, 20146 Germany Princeton, NJ 08540 [email protected] [email protected] David Ayala Bennett Chow organizer Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics University of Utah University of California, San Diego 155 S 1400 E La Jolla, CA 92093 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 [email protected] [email protected] Hans Ballmann Tobias Colding speaker Mathematisches Institut Courant Institute Universität Bonn New York University Beringstrasse 1 School of Education 53125 Bonn, Germany New York, NY 10003 [email protected] [email protected] Robert Bryant Eli Cooper Department of Mathematics Mathematics & Statistics Duke University University of Massachusetts, Amherst Physics Building, Science Drive Department of Mathematics & Statistics / Lederle Durham, NC 27708-0320 Graduate Resear Amherst, MA 01003-4515 [email protected] [email protected] Adrian Butscher Department of Mathematics Anda Degeratu University of Toronto Department of Mathematics 100 St. George Street, Sidney Smith Hall Duke University Toronto, ON M5S 3G3 Canada Physics Building, Box 90320 Durham, NC 27708 [email protected] [email protected] Gilles Carron Laboratoire jean Leray Harold Donnelly Université de Nantes Mathematics 2, rue de la Houssiniere, BP 92208 -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society (ISSN 0002- Call for Nominations for AMS Exemplary Program Prize

American Mathematical Society Notable textbooks from the AMS Graduate and undergraduate level publications suitable fo r use as textbooks and supplementary course reading. A Companion to Analysis A Second First and First Second Course in Analysis T. W. Korner, University of Cambridge, • '"l!.li43#i.JitJij England Basic Set Theory "This is a remarkable book. It provides deep A. Shen, Independent University of and invaluable insight in to many parts of Moscow, Moscow, Russia, and analysis, presented by an accompli shed N. K. Vereshchagin, Moscow State analyst. Korner covers all of the important Lomonosov University, Moscow, R ussia aspects of an advanced calculus course along with a discussion of other interesting topics." " ... the book is perfectly tailored to general -Professor Paul Sally, University of Chicago relativity .. There is also a fair number of good exercises." Graduate Studies in Mathematics, Volume 62; 2004; 590 pages; Hardcover; ISBN 0-8218-3447-9; -Professor Roman Smirnov, Dalhousie University List US$79; All AJviS members US$63; Student Mathematical Library, Volume 17; 2002; Order code GSM/62 116 pages; Sofi:cover; ISBN 0-82 18-2731-6; Li st US$22; All AlviS members US$18; Order code STML/17 • lili!.JUM4-1"4'1 Set Theory and Metric Spaces • ij;#i.Jit-iii Irving Kaplansky, Mathematical Analysis Sciences R esearch Institute, Berkeley, CA Second Edition "Kaplansky has a well -deserved reputation Elliott H . Lleb M ichael Loss Elliott H. Lieb, Princeton University, for his expository talents. The selection of Princeton, NJ, and Michael Loss, Georgia topics is excellent." I nstitute of Technology, Atlanta, GA -Professor Lance Small, UC San Diego AMS Chelsea Publishing, 1972; "I liked the book very much. -

EMS Newsletter No 38

CONTENTS EDITORIAL TEAM EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ROBIN WILSON Department of Pure Mathematics The Open University Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK e-mail: [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS STEEN MARKVORSEN Department of Mathematics Technical University of Denmark Building 303 NEWSLETTER No. 38 DK-2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark e-mail: [email protected] December 2000 KRZYSZTOF CIESIELSKI Mathematics Institute Jagiellonian University EMS News: Reymonta 4 Agenda, Editorial, Edinburgh Summer School, London meeting .................. 3 30-059 Kraków, Poland e-mail: [email protected] KATHLEEN QUINN Joint AMS-Scandinavia Meeting ................................................................. 11 The Open University [address as above] e-mail: [email protected] The World Mathematical Year in Europe ................................................... 12 SPECIALIST EDITORS INTERVIEWS The Pre-history of the EMS ......................................................................... 14 Steen Markvorsen [address as above] SOCIETIES Krzysztof Ciesielski [address as above] Interview with Sir Roger Penrose ............................................................... 17 EDUCATION Vinicio Villani Interview with Vadim G. Vizing .................................................................. 22 Dipartimento di Matematica Via Bounarotti, 2 56127 Pisa, Italy 2000 Anniversaries: John Napier (1550-1617) ........................................... 24 e-mail: [email protected] MATHEMATICAL PROBLEMS Societies: L’Unione Matematica -

Conjecture of De Giorgi Nikola Kamburov

A free boundary problem inspired by a Conjecture of De Giorgi :1hASSACHU6SETTS NSTITIJTF by OF TEC iC1LO0 Y Nikola Kamburov A.B., Princeton University (2007) L B23RAR 1 Submitted to the Department of Mathematics ARCHIVES in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2012 @ Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2012. All rights reserved. Author .............................. ............................ Department of Mathematics April 18, 2012 ~ A Certified by....... ........... David Jerison Professor of Mathematics Thesis Supervisor i '- Aii / / /I Accepted by.. y1 L/ L/ Gigliola Staffilani Abby Rockefeller Mauze Professor of Mathematics Chair, Committee on Graduate Students 2 A free boundary problem inspired by a Conjecture of De Giorgi by Nikola Kamburov Submitted to the Department of Mathematics on April 18, 2012, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract We study global monotone solutions of the free boundary problem that arises from minimizing the energy functional I(u) = f |Vu12 + V(U), where V(u) is the charac- teristic function of the interval (-1, 1). This functional is a close relative of the scalar Ginzburg-Landau functional J(u) = f IVu12 + W(u), where W(u) = (1 - u 2 )2 /2 is a standard double-well potential. According to a famous conjecture of De Giorgi, global critical points of J that are bounded and monotone in one direction have level sets that are hyperplanes, at least up to dimension 8. Recently, Del Pino, Kowalczyk and Wei gave an intricate fixed-point-argument construction of a counterexample in dimension 9, whose level sets "follow" the entire minimal non-planar graph, built by Bombieri, De Giorgi and Giusti (BdGG). -

Harmonic Functions on Manifolds with Nonnegative Ricci Curvature and Linear Volume Growth

Pacific Journal of Mathematics HARMONIC FUNCTIONS ON MANIFOLDS WITH NONNEGATIVE RICCI CURVATURE AND LINEAR VOLUME GROWTH Christina Sormani Volume 192 No. 1 January 2000 PACIFIC JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICS Vol. 192, No. 1, 2000 HARMONIC FUNCTIONS ON MANIFOLDS WITH NONNEGATIVE RICCI CURVATURE AND LINEAR VOLUME GROWTH Christina Sormani In this paper we prove that if a complete noncompact mani- fold with nonnegative Ricci curvature and linear volume growth has a nonconstant harmonic function of at most poly- nomial growth, then the manifold splits isometrically. Lower bounds on Ricci curvature limit the volumes of sets and the ex- istence of harmonic functions on Riemannian manifolds. In 1975, Shing Tung Yau proved that a complete noncompact manifold with nonnegative Ricci curvature has no nonconstant harmonic functions of sublinear growth [Yau2]. That is, if maxB (R) |f| lim sup p = 0(1) R→∞ R and if f is harmonic, then f is a constant. In the same paper, Yau used this result to prove that a complete noncompact manifold with nonnegative Ricci curvature has at least linear volume growth, Vol (B (R)) (2) lim inf p = C ∈ (0, ∞]. R→∞ R There are many manifolds with nonnegative Ricci curvature that actually have linear volume growth Vol (Bp(R)) (3) lim sup = V0 < ∞. R→∞ R Some interesting examples of such manifolds can be found in [So1]. In this paper, we prove the following theorem concerning harmonic func- tions on these manifolds. Theorem 1. Let M n be a complete noncompact manifold with nonnegative Ricci curvature and at most linear volume growth, Vol (Bp(R)) (4) lim sup = V0 < ∞.