Upper House Reform in Germany: the Commission for the Modernization of the Federal System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-Study*

brazilianpoliticalsciencereview ARTICLE Federalism, Bicameralism, and Institutional Change: General Trends and One Case-study* Marta Arretche University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil The article distinguishes federal states from bicameralism and mechanisms of territorial representation in order to examine the association of each with institutional change in 32 countries by using constitutional amendments as a proxy. It reveals that bicameralism tends to be a better predictor of constitutional stability than federalism. All of the bicameral cases that are associated with high rates of constitutional amendment are also federal states, including Brazil, India, Austria, and Malaysia. In order to explore the mechanisms explaining this unexpected outcome, the article also examines the voting behavior of Brazilian senators constitutional amendments proposals (CAPs). It shows that the Brazilian Senate is a partisan Chamber. The article concludes that regional influence over institutional change can be substantially reduced, even under symmetrical bicameralism in which the Senate acts as a second veto arena, when party discipline prevails over the cohesion of regional representation. Keywords: Federalism; Bicameralism; Senate; Institutional change; Brazil. well-established proposition in the institutional literature argues that federal Astates tend to take a slow reform path. Among other typical federal institutions, the second legislative body (the Senate) common to federal systems (Lijphart 1999; Stepan * The Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa no Estado -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

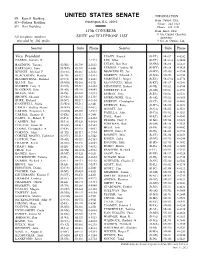

Senators Phone List.Pdf

UNITED STATES SENATE INFORMATION SR—Russell Building From Outside Dial: Washington, D.C. 20510 SD—Dirksen Building Senate—224–3121 SH—Hart Building House—225–3121 117th CONGRESS From Inside Dial: 0 for Capitol Operator All telephone numbers SUITE and TELEPHONE LIST Assistance preceded by 202 prefix 9 for an Outside Line Senator Suite Phone Senator Suite Phone Vice President LEAHY, Patrick (D-VT) SR-437 4-4242 HARRIS, Kamala D. 4-2424 LEE, Mike (R-UT) SR-361A 4-5444 BALDWIN, Tammy (D-WI) SH-709 4-5653 LUJAN, Ben Ray (D-NM) SR-498 4-6621 BARRASSO, John (R-WY) SD-307 4-6441 LUMMIS, Cynthia M. (R-WY) SR-124 4-3424 BENNET, Michael F. (D-CO) SR-261 4-5852 MANCHIN III, Joe (D-WV) SH-306 4-3954 BLACKBURN, Marsha (R-TN) SD-357 4-3344 MARKEY, Edward J. (D-MA) SD-255 4-2742 BLUMENTHAL, Richard (D-CT) SH-706 4-2823 MARSHALL, Roger (R-KS) SR-479A 4-4774 BLUNT, Roy (R-MO) SR-260 4-5721 McCONNELL, Mitch (R-KY) SR-317 4-2541 BOOKER, Cory A. (D-NJ) SH-717 4-3224 MENENDEZ, Robert (D-NJ) SH-528 4-4744 BOOZMAN, John (R-AR) SH-141 4-4843 MERKLEY, Jeff (D-OR) SH-531 4-3753 BRAUN, Mike (R-IN) SR-404 4-4814 MORAN, Jerry (R-KS) SD-521 4-6521 BROWN, Sherrod (D-OH) SH-503 4-2315 MURKOWSKI, Lisa (R-AK) SH-522 4-6665 BURR, Richard (R-NC) SR-217 4-3154 MURPHY, Christopher (D-CT) SH-136 4-4041 CANTWELL, Maria (D-WA) SH-511 4-3441 MURRAY, Patty (D-WA) SR-154 4-2621 CAPITO, Shelley Moore (R-WV) SR-172 4-6472 OSSOFF, Jon (D-GA) SR-455 4-3521 CARDIN, Benjamin L. -

Unicameralism and the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850 Val Nolan, Jr.*

DOCUMENT UNICAMERALISM AND THE INDIANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1850 VAL NOLAN, JR.* Bicameralism as a principle of legislative structure was given "casual, un- questioning acceptance" in the state constitutions adopted in the nineteenth century, states Willard Hurst in his recent study of main trends in the insti- tutional development of American law.1 Occasioning only mild and sporadic interest in the states in the post-Revolutionary period,2 problems of legislative * A.B. 1941, Indiana University; J.D. 1949; Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana Uni- versity School of Law. 1. HURST, THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN LAW, THE LAW MAKERS 88 (1950). "O 1ur two-chambered legislatures . were adopted mainly by default." Id. at 140. During this same period and by 1840 many city councils, unicameral in colonial days, became bicameral, the result of easy analogy to state governmental forms. The trend was reversed, and since 1900 most cities have come to use one chamber. MACDONALD, AmER- ICAN CITY GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION 49, 58, 169 (4th ed. 1946); MUNRO, MUNICIPAL GOVERN-MENT AND ADMINISTRATION C. XVIII (1930). 2. "[T]he [American] political theory of a second chamber was first formulated in the constitutional convention held in Philadelphia in 1787 and more systematically developed later in the Federalist." Carroll, The Background of Unicameralisnl and Bicameralism, in UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURES, THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL DEBATE HAND- BOOK, 1937-38, 42 (Aly ed. 1938). The legislature of the confederation was unicameral. ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, V. Early American proponents of a bicameral legislature founded their arguments on theoretical grounds. Some, like John Adams, advocated a second state legislative house to represent property and wealth. -

A Chamber of Though and Actions

CANADA’S SENATE A Chamber of THOUGHT AND ACTION © 2019 Senate of Canada I 1-800-267-7362 I [email protected] 2 ABOUT THE SENATE The Senate is the Upper House in Canada’s Senators also propose their own bills and generate Parliament. It unites a diverse group of discussion about issues of national importance in accomplished Canadians in service the collegial environment of the Senate Chamber, of their country. where ideas are debated on their merit. Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, The Senate was created to ensure Canada’s regions famously called it a chamber of sober second thought were represented in Parliament. Giving each region but it is much more than that. It is a source of ideas, an equal number of seats was meant to prevent inspiration and legislation in its own right. the more populous provinces from overpowering the smaller ones. Parliament’s 105 senators shape Canada’s future. Senators scrutinize legislation, suggest improvements Over the years, the role of senators has evolved. and fix mistakes. In a two-chamber parliament, the Senate In addition to representing their region, they also acts as a check on the power of the prime minister and advocate for underrepresented groups like cabinet. Any bill must pass both houses — the Senate Indigenous peoples, visible and linguistic and the House of Commons — before it can become law. minorities, and women. There shall be one Parliament for Canada, consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons. Constitution Act, 1867, section 17 3 HISTORY Canada would not exist were it not for the Senate. -

Asian-Parliaments.Pdf

Asian Parliaments Bangladesh Government type: parliamentary democracy unicameral National Parliament or Jatiya Sangsad; 300 seats elected by popular vote from single territorial constituencies (the constitutional amendment reserving 30 seats for women over and above the 300 regular parliament seats expired in May 2001); members serve fiveyear terms elections: last held 1 October 2001 (next to be held no later than January 2007) Bhutan Government type: monarchy; special treaty relationship with India unicameral National Assembly or Tshogdu (150 seats; 105 elected from village constituencies, 10 represent religious bodies, and 35 are designated by the monarch to represent government and other secular interests; members serve threeyear terms) elections: local elections last held August 2005 (next to be held in 2008) Burma Government type: military junta (leader not elected) Unicameral People's Assembly or Pyithu Hluttaw (485 seats; members elected by popular vote to serve fouryear terms) elections: last held 27 May 1990, but Assembly never allowed by junta to convene Cambodia Government type: multiparty democracy under a constitutional monarchy established in September 1993 Bicameral, consists of the National Assembly (123 seats; members elected by popular vote to serve fiveyear terms) and the Senate (61 seats; 2 members appointed by the monarch, 2 elected by the National Assembly, and 57 elected by parliamentarians and commune councils; members serve fiveyear terms) elections: National Assembly last held 27 July 2003 (next to be -

Australia's System of Government

61 Australia’s system of government Australia is a federation, a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. This means that Australia: Has a Queen, who resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Australia by a Governor-General. Is governed by a ministry headed by the Prime Minister. Has a two-chamber Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. A government, led by the Prime Minister, which must have a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Has eight State and Territory Parliaments. This model of government is often referred to as the Westminster System, because it derives from the United Kingdom parliament at Westminster. A Federation of States Australia is a federation of six states, each of which was until 1901 a separate British colony. The states – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania - each have their own governments, which in most respects are very similar to those of the federal government. Each state has a Governor, with a Premier as head of government. Each state also has a two-chambered Parliament, except Queensland which has had only one chamber since 1921. There are also two self-governing territories: the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The federal government has no power to override the decisions of state governments except in accordance with the federal Constitution, but it can and does exercise that power over territories. A Constitutional Monarchy Australia is an independent nation, but it shares a monarchy with the United Kingdom and many other countries, including Canada and New Zealand. The Queen is the head of the Commonwealth of Australia, but with her powers delegated to the Governor-General by the Constitution. -

DEWAN RAKYAT Standing Orders of the DEWAN RAKYAT

PARLIMEN MALAYSIA Peraturan-peraturan Majlis Mesyuarat DEWAN RAKYAT Standing Orders of the DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIMEN MALAYSIA Peraturan-peraturan Majlis Mesyuarat DEWAN RAKYAT Standing Orders of the DEWAN RAKYAT PARLIAMENT OF MALAYSIA Standing Orders of the DEWAN RAKYAT Fourteenth Publication June, 2018 DICETAK OLEH PERCETAKAN NASIONAL MALAYSIA BERHAD KUALA LUMPUR, 2018 www.printnasional.com.my email: [email protected] Tel.: 03-92366895 Faks: 03-92224773 165 STANDING ORDERS OF THE DEWAN RAKYAT These Standing Orders are made by the Dewan Rakyat in pursuance of Article 62(1) of the Federal Constitution. 166 TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLIC BUSINESS Standing Page Order 1. Proceedings of First Meetings of the House 175 after a General Election 2. Seating of Members 176 3. Election of a Yang di-Pertua 177 4. Procedure for election of Yang di-Pertua 177 4A. Leader of the House and Leader of the 179 Opposition 5. The Oath 180 6. Election of Timbalan Yang di-Pertua 181 7. Tuan Yang di-Pertua 181 8. Official Language 183 9. Duties of the Setiausaha 183 10. Official Reports 184 11. Sessions and Meetings 185 12. Sittings 186 13. Quorum 186 14. Order of Business 188 14A. Order of Business Special Chamber 190 15. Arrangement of Public Business 190 16. Special Chamber 190 17. Motion on Government Matter of Administration 192 18. Motion for Definite Matter of Urgent 193 Public Importance 19. Petitions 194 20. Papers 196 21. Questions 197 22. Notice of Questions 198 23. Contents of Questions 199 167 Standing Page Order 24. Manner of asking and answering questions 202 24A. -

Rules of the Kansas Senate

Rules of the Kansas Senate State of Kansas 2021-2024 January 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Rule 1. Time of Meetings.......................................................................... 5 Rule 2. Convening – Quorum – Assuming Duties of Chair...................... 5 Rule 3. Absence of Member...................................................................... 5 Rule 4. Order of Business and Session Proforma...................................... 5 Rule 5. Business in Order at Any Time..................................................... 6 Rule 6. Special Order................................................................................. 6 Rule 7. Standing Committees.................................................................... 7 Rule 8. Special and Select Committees..................................................... 8 Rule 9. Standing Committees – Duties of Chairperson, etc...................... 8 Rule 10. Vote in Senate Committee............................................................. 9 Rule 11. Committee Action on Bills and Resolutions................................. 9 Rule 12. Adversely Reported Bills and Resolutions................................... 10 Rule 13. When Bill or Concurrent Resolution Placed on General Orders.............................................................................. 10 Rule 14. Address the President – To Be Recognized – Speak But Twice on the Same Subject.................................................... 10 Rule 15. No Senator Shall Be Interrupted.................................................. -

The Argentine Elections: Systems and Candidates Carlos M

Volume XV, Issue 5 October 22 , 2007 The Argentine Elections: Systems and Candidates Carlos M. Regúnaga Constitutional and Legal Framework the most votes obtains two senate seats; and the third Argentina will hold presidential and congressional seat is assigned to the party with the second -largest elections on October 28. On the same date, local number of votes. elections will take place in 8 provinces; 16 other local Senators are elected for six years and the composition races were held earlier in the year. Given the of the Senate is renewed by thirds every two years. In uniqueness of Argentina’s electoral system, it is worth orde r to make this provision compatible with the reviewing how the elections are structured as well as electoral system described in the preceding paragraph, examining some of the key individual race s. the 24 districts are divided into three groups of 8 Argentina is a federal state, composed of 23 provinces. districts each. Every second year, 8 districts hold The federal district, the city of Buenos Aires, has the elections for senators. This year, for example, the city status of a province and elects its own executive and of Buenos Aires and the provinces of Chaco, Entre legislature and is represented in the national Congress Ríos, Neuquén, Río Negro, Salta, Santiago del Estero, like all other provinces. For t hat reason, all generic and Tierra del Fuego will elect three senators each. In references to “provinces” or “electoral districts” should the rest of the provinces, citizens will not vote for be understood to include the city of Buenos Aires as senators this year. -

The Unicameral Legislature

Citizens Research Council of Michigan Council 810 FARWELL BUILDING -- DETROIT 26 204 BAUCH BUILDING -- LANSING 23 Comments Number 706 FORMERLY BUREAU OF GOVERNMENTAL RESEARCH February 18, 1960 THE UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURE By Charles W. Shull, Ph. D. Recurrence of the suggestion of a single-house legislature for Michigan centers attention upon the narrowness of choice in terms of the number of legislative chambers. Where representative assemblies exist today, they are either composed of two houses and are called bicameral, or they possess but a single unit and are known as unicameral. The Congress of the United States has two branches – the Senate and the House of Representatives. All but one of the present state legislatures – that of Nebraska – are bicameral. On the other hand, only a handful of municipal councils or county boards retain the two-chambered pattern. This has not always been the case. The colonial legislatures of Delaware, Georgia, and Pennsylvania were single- chambered or unicameral; Vermont came into the United States of America with a one-house lawmaking assem- bly, having largely formed her Constitution of 1777 upon the basis of that of Pennsylvania. Early city councils in America diversely copied the so-called “federal analogy” of two-chambers rather extensively in the formative days of municipal governmental institutions. The American Revolution of 1776 served as a turning point in our experimentation with state legislative struc- ture. Shortly after the Declaration of Independence, Delaware and Georgia changed from the single-chamber type of British colony days to the alternate bicameral form, leaving Pennsylvania and its imitator Vermont main- taining single-house legislatures. -

National Senate of Argentina Located in a Traditionally Elegant

CASE STUDY National Senate of Argentina BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA Challenge Sometimes the official TV channel of the National Senate of Argentina (SENADO TV) encountered inter- ferences due to the use of wireless microphones in the UHF range. In some instances, the audio signal even broke off for a few seconds – an unacceptable flaw that needed remedy. Solution With the newly-installed Sennheiser SpeechLine Digital Wireless (SLDW) system that works in the range of 1.9 GHz, interferences are a thing of the past. Transmission is now coded against competing signals and events run smoothly. Located in a traditionally elegant stone building … “Interference problems SENADO TV ARGENTINA covers press conferences, committee meetings, have vanished. What’s public hearings and sessions of the National Senate. The Argentinian TV channel was already equipped with Sennheiser products, and in most situa- more: The SpeechLine tions, those microphones worked well, even in unfavorable acoustic surround- series is easy to use ings. “As is often the case with legal institutions, we are located in a building from the beginning of the 20th century”, the channel’s technicians, Hugo and elegant.” Boria and Ariel Cravero, report. “You can imagine what that means in terms of architecture and materials used – we have vast halls of marble that we need our wireless audio equipment to work in.” Hugo Boria Chief Audio Officer … a national TV channel is faced with serious sound challenges … & Ariel Cravero Deputy Director of Audiovisual But according to the two audio experts, those conditions were not the main Communication issue that led to the purchase of the SLDW series.