Architecture Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWS from the GETTY DATE: June 10, 2009 for IMMEDIATE RELASE

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY DATE: June 10, 2009 FOR IMMEDIATE RELASE GETTY PARTICIPATES IN 2009 GUADALAJARA BOOK FAIR Getty Research Institute and Getty Publications to help represent Los Angeles in the world’s largest Spanish-language literary event Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles At the Museo de las Artes, Guadalajara, Mexico November 27, 2009–January 31, 2010 LOS ANGELES—The Getty today announced its participation in the 2009 International Book Fair in Guadalajara (Feria Internacional del Libro de Guadalajara or FIL), the world’s largest Spanish-language literary event. This year, the city of Los Angeles has been invited as the fair’s guest of honor – the first municipality to be chosen for this recognition, which is usually bestowed on a country or a region. Both Getty Publications and the Getty Research Institute (GRI) will participate in the fair for the first time. Getty Publications will showcase many recent publications, including a wide selection of Spanish-language titles, and the Getty Research Institute will present the extraordinary exhibition, Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles, which includes 110 rarely seen photographs from the GRI’s Julius Shulman photography archive, which was acquired by the Getty Research Institute in 2005 and contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies. “We are proud to help tell Los Angeles’ story with this powerful exhibition of iconic and also surprising images of the city’s growth,” said Wim de Wit, the GRI’s senior curator of architecture and design. -

The German/American Exchange on Nazi-Era Art Provenance Research

2017 PREP Exchanges The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (February 5–10) Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (September 24–29) 2018 PREP Exchanges The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (February 25–March 2) Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich (October 8–12) 2019 PREP Exchanges Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Spring) Smithsonian Institution, Provenance Research Initiative, Washington, D.C. (Fall) Major support for the German/American Provenance Research Exchange Program comes from The German Program for Transatlantic Encounters, financed by the European Recovery Program through Germany's Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, and its Commissioner for Culture and the Media Additional funding comes from the PREP Partner Institutions, The German/American Exchange on the Smithsonian Women's Committee, James P. Hayes, Nazi-Era Art Provenance Research Suzanne and Norman Cohn, and the Ferdinand-Möller-Stiftung, Berlin 3RD PREP Exchange in Los Angeles February 25 — March 2, 2018 Front cover: Photos and auction catalogs from the 1910s in the Getty Research Institute’s provenance research holdings The Getty Research Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive Los Angeles, CA 90049 © 2018Paul J.Getty Trust ORGANIZING PARTNERS Smithsonian Provenance Research Initiative, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz—Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation—National Museums in Berlin) PARTNERS The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York The Getty Research -

News from the Getty

The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 400 Tel 310 440 7360 Communications Department Los Angeles, California 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 www.getty.edu [email protected] NEWS FROM THE GETTY DATE: February 9, 2010 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GETTY PARTICIPATES IN 2010 ARCOmadrid Getty Research Institute to help represent Los Angeles at International Contemporary Art Fair Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles At the Canal de Isabel II, Madrid, Spain February 16–May 16, 2010 Shulman, Julius. Simon Rodia's Towers (Los Angeles, Calif.), 1967. Gelatin silver. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission. Julius Shulman Photography Archive, Research Library at the Getty Research Institute (2004.R.10) LOS ANGELES—The Getty Research Institute today announced its participation in the 2010 ARCOmadrid, an international contemporary arts fair. For the first time in the Fair’s 29-year history, ARCOmadrid is honoring a city, rather than a country, in a special exhibition titled Panorama: Los Angeles, recognizing L.A. as one of the most prolific and vibrant contemporary arts centers in the international art world. As part of ARCOmadrid’s exciting roster of satellite exhibitions, the Getty Research Institute (GRI) will showcase the extraordinary exhibition Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles, in collaboration with Comunidad de Madrid, which includes over 100 rarely seen photographs from the GRI’s Julius Shulman photography archive, which was acquired in 2005 and contains over 260,000 color and black-and-white negatives, prints, and transparencies. “We are delighted that the Getty Research Institute is bringing Julius Shulman’s Los Angeles to ARCOMadrid. -

DATE: July 09, 2021 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Getty Exhibition

DATE: July 09, 2021 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Getty Exhibition Reassembles Medieval Italian Triptych Paolo Veneziano: Art and Devotion in 14th-Century Venice is the first monographic exhibition on the artist in U.S. The Crucifixion, about 1340-1345 Paolo Veneziano (Italian (Venetian), about 1295 - about 1362) Tempera and gold leaf on panel Unframed: 33.9 × 41.1 cm (13 5/16 × 16 3/16 in.) Framed: 37.2 × 45.4 × 5.7 cm (14 5/8 × 17 7/8 × 2 1/4 in.) National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.143 LOS ANGELES - Paolo Veneziano (about 1295–about 1362) was the premier painter in late medieval Venice, producing religious works ranging from large complex altarpieces to small paintings used by Christians for personal devotion. A new exhibition, on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, from July 13 through October 3, 2021, brings together numerous paintings that reveal the delicate beauty and exquisite colors that distinguish Paolo Veneziano’s art. The centerpiece of the show reunites painted panels that originally belonged together but are today housed in different collections. “It is fairly commonplace for museums around the world to own fragments of what were once larger ensembles, dismantled in later centuries for sale on the art market,” explains Timothy Potts, Maria Hummer-Tuttle and Robert Tuttle Director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “Paolo Veneziano: Art and Devotion in 14th-Century Venice presents a rare exception: a completely intact triptych for personal devotion, on loan from the National Gallery of Parma, Italy. The appearance of this triptych was the basis for the reconstruction of an almost identical triptych, the so-called Worcester triptych, reassembled for the first time in this exhibition.” Portable devotional triptychs, self-supporting and with closable shutters, were regularly made by artists and craftspeople in Venice throughout the fourteenth century. -

Phase I Stage A.2 | CLOSURES and DETOUR ROUTES: Mulholland Bridge Demolition Over I-405

Phase I Stage A.2 | CLOSURES AND DETOUR ROUTES: Mulholland Bridge Demolition Over I-405 SB US-101 TO SB I-405 CONNECTOR (CLOSED) NB US-101 TO SB-I-405 CONNECTOR SB I-405 (CLOSED) NB ON-RAMP (REDUCED LANES BETWEEN US-101 @ VENTURA BLVD AND VALLEY VISTA BLVD) (OPEN) SB OFF-RAMP @ VENTURA BLVD (CLOSED) SB ON-RAMP @ VENTURA BLVD (CLOSED) SB OFF-RAMP @ VALLEY VISTA BLVD (OPEN — ALL SB FREEWAY TRAFFIC MUST EXIT AT SEPULVEDA BLVD) NB OFF-RAMP @ VENTURA BLVD SB ON-RAMP @ VALLEY VISTA BLVD (CLOSED) (CLOSED) SB I-405 NB I-405 (CLOSED BETWEEN (CLOSED BETWEEN VALLEY VISTA BLVD GETTY CENTER DR AND GETTY CENTER DR) AND VENTURA BLVD) SEPULVEDA TUNNEL (OPEN — NO TRUCKS) SB ON-/OFF-RAMPS @ SKIRBALL CENTER DR (CLOSED) SKIRBALL CENTER DR MULHOLLAND DR BETWEEN HIGH SCHOOL EGRESS @ SEPULVEDA BLVD AND SKIRBALL CENTER DR (TRAFFIC CONTROL OFFICER) (CLOSED) NB ON-/OFF-RAMPS @ SKIRBALL CENTER DR (CLOSED) Reduced Lanes NOTE: Freeway connector closure detours are shown on the NOTE: NB I-405 — REDUCED LANES BETWEEN DETOUR ROUTES FOR CLOSED I-405 CONNECTORS exhibit. I-10 AND SEPULVEDA BLVD/GETTY CENTER DR ALL NB FREEWAY TRAFFIC MUST EXIT AT SEPULVEDA BLVD SB OFF-RAMP @ SEPULVEDA BLVD/ GETTY CENTER DR (CLOSED) SB RAMPS @ SEPULVEDA BLVD/ GETTY CENTER DR (TRAFFIC CONTROL OFFICER) NB ON-RAMP @ SEPULVEDA BLVD/GETTY CENTER DR (CLOSED) SB ON-RAMP @ SEPULVEDA BLVD/ NB OFF-RAMP @ SEPULVEDA BVLD/GETTY CENTER DR GETTY CENTER DR (TRAFFIC CONTROL OFFICER — (OPEN) ALL NB FREEWAY TRAFFIC MUST EXIT AT SEPULVEDA BLVD) Phase I Stage A.2 | CLOSURES AND DETOUR ROUTES: Mulholland Bridge -

Datebook: Shots of Old Route 66, Dreamlike Paintings and Garments Fashioned from Paper

Datebook: Shots of old Route 66, dreamlike paintings and garments fashioned from paper By CAROLINA A. MIRANDA JUL 12, 2018 | 11:00 AM "Blue Swallow Motel," 1990, by Steve Fitch for “Vanishing Vernacular” at Kopeikin. (Steve Fitch / Kopeikin) A record of roadside vernacular and paintings that explore the intimate and the fantastical. Plus: a butch parade and an art-meets-sports night. Here are nine exhibitions and events to check out in the coming week: latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-datebook-vanishing-vernacular-steve-fitch-story.html# Steve Fitch, “Vanishing Vernacular,” at Kopeikin Gallery. Fitch, who is known for documenting the American West, takes on the slowly disappearing neon signage and vernacular architecture of the old Route 66 in his latest project “Vanishing Vernacular,” which is both an exhibition and book (published in the spring by George F. Thompson Publishing). For his show at Kopeikin, he gathers images of drive-ins, roadside signage and fancifully- designed motels that once channeled the romance of the open road, but which have now been sidelined by the interstate highway system. Opens Saturday at 6 p.m. and runs through Aug. 25. 2766 S. La Cienega Blvd., Culver City, kopeikingallery.com. Jonny Negron, “Small Map of Heaven,” at Château Shatto. Born in Puerto Rico and based in New York, Negron has long been inspired by the bright colors and sharp lines of comic books and Japanese woodblock prints. But he employs the forms in ways that are resolutely his own, creating intimate scenes that also feature aspects of the fantastical — such as lush landscapes and ghostly figures. -

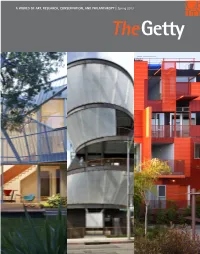

Thegetty INSIDE This Issue

A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Spring 2013 TheGetty INSIDE this issue The J. Paul Getty Trust is a cultural Table of CONTENTS and philanthropic institution dedicated to critical thinking in the presentation, conservation, and interpretation of the world’s artistic President’s Message 7 legacy. Through the collective and individual work of its constituent Pacific Standard Time Presents: 8 Programs—Getty Conservation Modern Architecture in L.A. Institute, Getty Foundation, J. Paul Getty Museum, and Getty Research Institute—it pursues its mission in Los Minding the Gap: The Role of Contemporary 11 Angeles and throughout the world, Architecture in the Historic Environment serving both the general interested public and a wide range of In Focus: Ed Ruscha 14 professional communities with the conviction that a greater and more Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future 16 profound sensitivity to and knowledge of the visual arts and their many histories is crucial to the promotion Sponsor Spotlight 18 of a vital and civil society. Behind the Scenes: Grantmaking 20 at the Getty New Acquisitions 25 FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION From The Iris 26 Margaret Malone Cultural Media Inc 1001 W. Van Buren Street New from Getty Publications 28 Chicago, IL, 60607 [email protected] From the Vault 31 (312) 593-3355 On the cover, from left to right: Palms House (detail), Venice, California, 2011, Daly Genik Architects. Photograph Jason Schmidt. © Jason Schmidt; Samitaur Tower (detail), Culver City, California, 2008–10, Eric Owen Moss. Photo: Tom Bonner. © 2011 Tom Bonner; Formosa 1140 (detail), West Hollywood, California, Lorcan O’Herlihy, 2008, © 2009 Lawrence Anderson/Esto © 2013 Published by the J. -

Myths About Living in Los Angeles

There are many pre-conceived notions floating around about Los Angeles. Are your ideas of LA based more on Hollywood than on reality? Here are some top myths and misconceptions about the City of Angels. 1. The weather is always sunny and warm. While it is mainly sunny in LA throughout the year, contrary to popular belief, LA does get chilly. Chilly meaning it dips into the low 50s and 40s, especially in the winter months of December – January. In fact, a layer of marine clouds that hangs over the city throughout the summer, known as June gloom, makes most mornings overcast until around noon. Even more: it rains. So you won’t need to retire your winter jacket or umbrella just yet! (Photo: Calvin Fleming/Flickr) 2. It’s overcrowded! With about 4 million people in 468 square miles, LA is crowded. It is the second most populous area in the U.S., besides New York City. However, there are over 80 neighborhoods spread out throughout the city. There are always places like Malibu, scenic hiking trails, and other quieter, more-removed areas to go to if you feel overwhelmed. And you don’t have to go very far because right here on campus, UCLA has expansive green lawns, a 7-acre botanical garden, and a 5-acre sculpture garden where you can relax and take in the greenery. (Photo: waltarrrrr/Flickr) 3. People are rich, fake, spoiled, stuck-up, and everyone is rude! And what city doesn’t have people that are like this? In LA, there are very rich people, very poor people, and people in-between. -

Susan Steinhauser and Daniel Greenberg

The Getty A WORLD OF ART, RESEARCH, CONSERVATION, AND PHILANTHROPY | Fall 2014 INSIDE THIS ISSUE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE The J. Paul Getty Trust is a cultural TABLE OF CONTENTS by James Cuno and philanthropic institution President and CEO, the J. Paul Getty Trust dedicated to critical thinking in the presentation, conservation, and interpretation of the world’s artistic President’s Message 3 legacy. Through the collective and Last year the Getty inaugurated the J. Paul Getty Medal to honor individual work of its constituent New and Noteworthy 4 extraordinary achievement in the fields of museology, art historical programs—Getty Conservation research, philanthropy, conservation, and conservation science. The first Institute, Getty Foundation, J. Paul Lord Jacob Rothschild to Receive Getty Medal 6 recipients were Harold M. Williams and Nancy Englander, who were Getty Museum, and Getty Research chosen for their role in creating the Getty as a global leader in art Institute—it pursues its mission in Los Angeles and throughout the world, Conserving an Ancient Treasure 10 history, conservation, and museum practice. This year we are honoring serving both the general interested Lord Jacob Rothschild OM GBE for his extraordinary leadership and public and a wide range of A Project of Seismic Importance 16 contributions to the arts. professional communities with the In November, we will bestow the J. Paul Getty Medal on Lord Rothschild, conviction that a greater and more WWI: War of Images, Images of War 20 profound sensitivity to and knowledge a most distinguished leader in our field. He has served as chairman of of the visual arts and their many several of the world’s most important art-, architecture-, and heritage- histories is crucial to the promotion Caravaggio and Rubens Together in Vienna 24 related organizations, and is renowned for this dedication to the of a vital and civil society. -

DATE: October 7, 2020 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE

DATE: October 7, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE GETTY RESEARCH INSTITUTE PRESENTS 12 SUNSETS, AN INTERACTIVE WEBSITE EXPLORING 12 YEARS OF ED RUSCHA’S PHOTOS OF SUNSET BLVD 12Sunsets.Getty.edu Cineramadome on Sunset Boulevard photographed by Ed Ruscha in 1973, 1990, and 2007, respectively. Streets of Los Angeles Archive. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.1. © Ed Ruscha LOS ANGELES – The Getty Research Institute (GRI) launched today 12 Sunsets: Exploring Ed Ruscha’s Archive, an interactive website that allows users to discover thousands of photographs of Sunset Boulevard taken by artist Ed Ruscha between 1965 and 2007. “Ed Ruscha’s engagement with the Los Angeles cityscape is profound. Since the mid-1960s he has taken more than a half-million photographs of the streets of Los Angeles, which have been at Getty Research Institute since 2012,” said Mary Miller, director of Getty Research Institute. “We aim to activate this rich material and make it widely accessible and appealing to anyone interested in art or the recent history of this great city. The vast majority of these photographs have never been seen before, and making them accessible opens up new avenues for inquiry about one of the most significant artists of the postwar period, as well as a major part of Los Angeles history.” The website, designed by Stamen Design working with Getty Digital, allows users to “drive” down Sunset Boulevard in 12 different years between 1965 and 2007, as well as to view, search, and compare the more than 65,000 photographs of this key urban artery. Entering this user-friendly website, visitors can navigate Sunset Boulevard in a particular year, browsing tens of thousands of geotagged photos, with images from both sides of the street. -

Housing Moving to Los Angeles?

STANFORD YOUNG ALUMNI GUIDE nightlife Los Ange es housing recreation dining tips Ready to enjoy Los Angeles? In-the-know Stanford young alums have shared the best tips, tricks and fabulous destinations to help you get the most out of this vibrant city. Dining Contents Dining Young alums love to dine at these 2 delicious destinations. Nightlife Nightlife According to young alums, these are 6 the best spots to kick up your heels and enjoy an evening with friends. Recreation These are the places to go to have Recreation 8 fun and hang out (you’ll probably spot a young alum or two!). Housing Be sure to check out the best young 11 alumni ’hoods in Los Angeles. Housing Tips Young alums give their general advice 13 on things to keep in mind as you explore Los Angeles. Tips LOS ANGELES 1 Dining Don’t miss these young alumni- Dining approved places for the tastiest meals in town. 800 Degrees Great and inexpensive Neapolitan pizza. - CYNTHIA H., ’10 Alfred Coffee & Kitchen The newest organic coffee in town. - AMY A., ’06 Bella Pita This hole in the wall is a hidden gem. The fresh and healthy food is outstanding and you can’t beat the prices. - MICHELLE K., ’05 Bibigo Korean, also on Beverly. - AYESHA R., ’14 Bossa Nova Amazing Brazilian food and centrally located. - CORINNE P., ’09 Bottega Louie Best macarons. Also great for brunch. - ANONYMOUS Bru Haus Impressive international beer selection, good American food and lots of TVs. - MEGHAN V., ’11 C&O Cucina Garlic knots. - ANONYMOUS Cafe Gratitude Delicious vegan cuisine and a very “LA” experience. -

The Westside Neigbourhoods

NEIGHBOURHOOD FACTSHEET PETERSEN AUTOMOTIVE MUSEUM The Westside neigbourhoods The westside is known for its top restaurants, high-end shopping, SUGGESTED DINING palm tree lined streets and acclaimed cultural attractions. Beverly Hills: Maude Century City: Hinoki & the Bird is known worldwide as a premier destination for luxury. Beverly Hills: Mid-City/Mid-Wilshire: The Original Farmer’s Market Stroll along world-famous Rodeo Drive and admire the incomparable Westwood: 800 Degrees Neapolitan Pizzeria designer boutiques. Sawtelle/Japantown: Tsujita Artisan Noodles Century City: Born from the backlot of historic Fox Studios, Century City Brentwood: Brentwood County Mart is home to gleaming high rises and luxe hotels, where movers and shakers Culver City: Helms Bakery District work and play. SHOPPING Mid-City/Mid-Wilshire: is a vital hub for culture, art and dining. Stroll Beverly Hills: Rodeo Drive & Beverly Centre through the La Brea Tar Pits and peruse the impressive collection of Century City: Westfield Century City exhibits at the L.A. County Museum of Art. Shop at The Grove and grab a Mid-City/Mid-Wilshire: The Grove & Original bite at The Original Farmer’s Market. Farmer’s Market Westwood: Visit the UCLA campus or explore the Hammer Museum’s Westwood: Westwood Village renowned collections of modern and Impressionist art. Sawtelle/Japantown: Sawtelle Blvd Brentwood: Brentwood County Mart a slice of Japanese culture on the Westside. The Sawtelle/Japantown: Culver City: Westfield Culver City historic neighbourhood has become a foodie paradise, home to authentic Japanese restaurants, modern eateries, artisan coffee and ramen shops. TRANSPORTATION Take Metro Expo Line from Culver City Brentwood: is one of L.A.’s most affluent neighbourhoods, known for its Downtown: palatial estates, tree-lined streets, A-list residents and home of the famed towards Union Station – 45 mins Getty Center.