Juvenile Firesetting: a Research Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

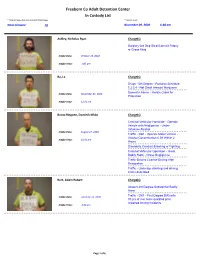

In Custody List **Total Inmates Does Not Include ICE Detainees **Current As Of: Total Inmates: 28 November 09, 2020 6:48 Am

Freeborn Co Adult Detenton Center In Custody List **Total Inmates does not include ICE Detainees **Current as of: Total Inmates: 28 November 09, 2020 6:48 am Ashley, Nicholas Ryan Charge(s) Burglary-3rd Deg-Steal/Commit Felony or Gross Misd Intake Date: October 15, 2020 Intake Time: 1:05 pm Ba, La Charge(s) Drugs - 5th Degree - Possess Schedule 1,2,3,4 - Not Small Amount Marijuana Domestic Abuse - Violate Order for Intake Date: November 01, 2020 Protection Intake Time: 12:21 am Boots-Ringoen, Dominik Nikko Charge(s) Criminal Vehicular Homicide - Operate Vehicle with Negligence - Under Influence Alcohol Intake Date: August 27, 2020 Traffic - DWI - Operate Motor Vehicle - Alcohol Concentration 0.08 Within 2 Intake Time: 10:31 pm Hours Disorderly Conduct-Brawling or Fighting Criminal Vehicular Operation - Great Bodily Harm - Gross Negligence Traffic-Drivers License-Driving After Revocation Traffic - Underage drinking and driving; Crime described Burt, Adam Robert Charge(s) Assault-3rd Degree-Substantial Bodily Harm Traffic - DWI - First-Degree DWI;w/in Intake Date: February 14, 2020 10 yrs of 3 or more qualified prior impaired driving incidents Intake Time: 4:43 pm Page 1 of 6 Everet, Michael Leonard Charge(s) Harassment; Restraining Order - Violate and knows of temporary or restraining order Intake Date: November 06, 2020 Intake Time: 5:53 pm Fishel, Adam Dwayne Charge(s) Fleeing a Peace Officer in a Motor Vehicle Traffic - DWI - Operate Motor Vehicle - Intake Date: November 01, 2020 Alcohol Concentration 0.08 Within 2 Hours Intake Time: -

Fire and Arson Scene Evidence: a Guide for Public Safety Personnel

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice FireFire andand ArsonArson SceneScene Evidence:Evidence: A Guide for Public Safety Personnel Research Report U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street N.W. Washington, DC 20531 Janet Reno Attorney General Daniel Marcus Acting Associate Attorney General Mary Lou Leary Acting Assistant Attorney General Julie E. Samuels Acting Director, National Institute of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice World Wide Web Site World Wide Web Site http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/nij Fire and Arson Scene Evidence: A Guide for Public Safety Personnel Written and Approved by the Technical Working Group on Fire/Arson Scene Investigation June 2000 NCJ 181584 Julie E. Samuels Acting Director David G. Boyd, Ph.D. Deputy Director Richard M. Rau, Ph.D. Project Monitor Opinions or points of view expressed in this document represent a consensus of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the U.S. Department of Justice. The National Institute of Justice is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Message From the Attorney General ctions taken at the outset of an investigation at a fire and Aarson scene can play a pivotal role in the resolution of a case. Careful, thorough investigation is key to ensuring that potential physical evidence is not tainted or destroyed or potential witnesses overlooked. -

THE CRIME of ARSON Paul Sadler, Jr

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 41 | Issue 3 Article 4 1950 The rC ime of Arson Paul Jr. Sadler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Paul Jr. Sadler, The rC ime of Arson, 41 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 290 (1950-1951) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE CRIME OF ARSON Paul Sadler, Jr. The following article is from a thesis the author prepared while pursuing his studies in Social Relations at Harvard University, from which he received his A.B. degree in June, -1950. Mr. Sadler is currently employed as a fire investigator adjuster for the General Adjustment Bureau, Inc., Boston, Mass.-EDrroR. I The crime of arson is an extraordinarily complex one by its definition alone. Its complexity makes many difficulties to the student. It also gives the perpetrator some advantages. To begin with, arson, like murder and most admirality crimes, exists in several degrees of indict- ment. These degrees are wholly dependent upon the type and use of the structure or property burned, degree of involvement of participants, and often the time of day in which the crime is committed.' But what degrees now exist are only created by modern statutory defini- tion over and above the original common law of England, which law, in comparison with 20th century statutes, seems very defective in scope. -

Should Commission of a Contemporaneous Arson, Burglary

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 49 | Number 1 Article 1 2009 Should Commission of a Contemporaneous Arson, Burglary, Kidnapping, Rape, or Robbery Be Sufficient to Make a Murderer Eligible for a Death Sentence? - An Empirical and Normative Analysis David McCord Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David McCord, Should Commission of a Contemporaneous Arson, Burglary, Kidnapping, Rape, or Robbery Be Sufficient to Make a Murderer Eligible for a Death Sentence? - An Empirical and Normative Analysis, 49 Santa Clara L. Rev. 1 (2009). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol49/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHOULD COMMISSION OF A CONTEMPORANEOUS ARSON, BURGLARY, KIDNAPPING, RAPE, OR ROBBERY BE SUFFICIENT TO MAKE A MURDERER ELIGIBLE FOR A DEATH SENTENCE?-AN EMPIRICAL AND NORMATIVE ANALYSIS By David McCord* INTRODUCTION Most death penalty jurisdictions make a murderer death- eligible if the murder was committed contemporaneously with one of five felonies: arson, burglary, kidnapping, rape, or robbery.1 In recent years, however, this traditional approach has been challenged by two blue-ribbon panels-the Illinois Commission on Capital Punishment and the Massachusetts Governor's Council on Capital Punishment-both of which advocated abolition of these five felonies as death-eligibility aggravators.2 The stakes in this debate are high because these five felonies-hereinafter "the contemporaneous felonies"-are frequent companions of murder: over sixty percent of death-eligible defendants contemporaneously commit at least one of them,3 and robbery alone qualifies more murderers for death-eligibility than any other * Professor of Law, Drake University Law School; J.D. -

Reducing Residential Arson National Arson Awareness Week Media Kit May 5-11, 2013 2013 Arson Awareness Week: “Reducing Residential Arson.”

U.S. Fire Administration Reducing Residential Arson National Arson Awareness Week Media Kit May 5-11, 2013 2013 Arson Awareness Week: “Reducing Residential Arson.” The U.S. Fire Administration (USFA) and its partners Excitement will use the week of May 5-11 to focus public attention on residential arson and provide communities with Most excitement fires are nuisance fires but may esca- tools to reduce the incidence of this crime. The goal late to homes. Excitement-motivated arsonists desire for this year’s Arson Awareness Week is to provide the thrill associated with setting the fire and relish the all residents with strategies to combat arson in their attention it brings. They rarely intend to injure people neighborhoods. but don’t have the requisite knowledge to keep the fires under control. Reducing Residential Arson: Why Arson? Revenge The motivations behind the burning of homes are curiosity, vandalism, concealing another crime, excite- According to the National Center for the Analysis of ment, revenge and insurance fraud or arson for profit. Violent Crime, the most common motive (41 percent) for a serial arsonist is revenge. An arsonist will target Curiosity the home of someone in retaliation for an actual or perceived injustice against him or her. Curiosity fires are most often set by juveniles. The mis- use of fire has many variables including age, motivation Insurance Fraud or Arson for Profit for firesetting behavior, type of fires set, ignition materi- als used to set the fire, and the child’s understanding and Arson for profit is insurance fraud, a criminal method limitations of fire. -

The American Felony Murder Rule: Purpose and Effect

The American Felony Murder Rule: Purpose and Effect Daniel Ganz 21090905 UC Berkeley, Spring 2012 Legal Studies Honors Thesis Supervised by Professor Richard Perry Ganz 1 I. Abstract Most US states have a felony murder rule, which allows prosecutors to charge felons with murder for any death that occurs during and because of the commission of the felony. This allows the felon to be convicted with murder without requiring the prosecution to prove the mens rea that would otherwise be necessary for a murder conviction. Much of the legal scholarship indicates that the purpose of the felony murder rule is to deter felonies and to make felons limit their use of violence while they're committing the felony by making the felon internalize more fully the negative consequences of their actions. It's unclear whether legislatures that adopt felony murder rules are more concerned with deterring criminal behavior or making criminals less violent when committing felonies. We analyze judicial decisions to infer what judges believed were the intentions of the legislatures that adopted felony murder statutes. We also use regression analysis to determine whether felony murder statutes are correlated with lower crime rates or lower rates of the average number of deaths that occur during felonies. We do this both by modeling felony rates and rates of felony- related deaths as a function of whether a state has a felony murder rule, and by determining how felony rates and rates of felony-related deaths change when a state adopts or abolishes a felony murder rule. Our results indicate that the felony murder rule does not have a significant effect on crime rates or crime-related death rates. -

Statutes of Limitation for Prosecution of Offenses Against Children (Last Updated August 2012)

Statutes of Limitation for Prosecution of Offenses Against Children (last updated August 2012) This compilation includes statutes that establish, toll, extend, or eliminate time limitations for charging criminal offenses relating specifically to child victims. Every statute included either specifically mentions child victims or makes reference to a statute that does. This is not a statutory compilation of all criminal statute of limitations laws. General statutes of limitations that apply to all crimes without specific reference to the age of the victim or children as a class of victims are omitted. Please feel free to contact NDAA for help in ensuring compliance with all of your jurisdiction’s applicable statutes of limitation. Table of Contents: TABLE OF CONTENTS:............................................................................................................................................... 1 ALABAMA .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 ALA. CODE § 15-3-5 (2012). Offenses having no limitation.....................................................................................4 ALASKA ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 ALASKA STAT. § 12.10.010 (2012). General time limitations...................................................................................4 -

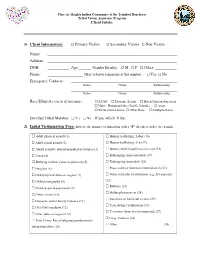

Client Intake Form

Cher-Ae Heights Indian Community of the Trinidad Rancheria Tribal Victim Assistance Program Client Intake 1) Client Information: ☐ Primary Victim ☐ Secondary Victim ☐ Non-Victim Name: __________________________________________________________________ Address: __________________________________________________________________ DOB: ___________ Age ______ Gender Identity: ☐ M ☐ F ☐ Other: ___________ Phone: __________________ Okay to leave a message at this number ☐ Yes ☐ No Emergency Contacts: ______________________________________________________ Name Phone Relationship ______________________________________________________ Name Phone Relationship Race/Ethnicity (check all that apply) ☐ AI/AN ☐ Hispanic/Latino ☐ Black/African American ☐ Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander ☐ Asian ☐ White (Non-Latino) ☐ Other Race ☐ Multiple Races Enrolled Tribal Member: ☐ Yes ☐ No If yes, which Tribe: _________________________ 2) Initial Victimization Type: Indicate the primary victimization with a “P” all others with a check mark ☐ Adult physical assault (1) ☐ Human trafficking: Labor (16) ☐ Human trafficking: Sex (17) ☐ Adult sexual assault (2) ☐ Identity theft/fraud/financial crime (18) ☐ Adults sexually abused/assaulted as children (3) ☐ Kidnapping (non-custodial) (19) ☐ Arson (4) ☐ Bullying (verbal, cyber or physical) (5) ☐ Kidnapping (custodial) (20) ☐ Mass violence (domestic/international) (21) ☐ Burglary (6) ☐ Other vehicular victimization (e.g., hit and run) ☐ Child physical abuse or neglect (7) (22) ☐ Child pornography (8) ☐ Robbery (23) ☐ -

ARSON in the FOURTH DEGREE (Recklessly Damaging Property by Fire Or Explosion) Penal Law § 150.05 (Committed on Or After Sept

ARSON IN THE FOURTH DEGREE (Recklessly Damaging Property by Fire or Explosion) Penal Law § 150.05 (Committed on or after Sept. 1, 1979) The (specify) count is Arson in the Fourth Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Arson in the Fourth Degree when that person recklessly damages a building [or motor vehicle] by intentionally starting a fire [or causing an explosion]. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: A person RECKLESSLY damages a building [or motor vehicle]: when that person does so by engaging in conduct which creates or contributes to a substantial and unjustifiable risk that such damage will occur, and when he or she is aware of and consciously disregards that risk, and when the risk is of such nature and degree that disregarding it constitutes a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable person would observe in the situation.1 [NOTE: Add if appropriate: A person who creates such a risk but is unaware of it solely by reason of his or her voluntary intoxication also acts recklessly.2] 1 See Penal Law § 15.05(3); People v. Boutin, 75 NY2d 692, 696 (1990). 2 See Penal Law § 15.05(3); People v. Boutin, 75 NY2d 692, 696 (1990). [NOTE: Add, where appropriate: In addition to its ordinary meaning, the term BUILDING includes any structure, vehicle or watercraft used for overnight lodging of persons, or used by persons for carrying on business therein.3] [NOTE: Add, where appropriate: MOTOR VEHICLE includes every vehicle operated or driven upon a public highway which is propelled by any power other than muscular power.4] A person DAMAGES A BUILDING [or MOTOR VEHICLE] when that person causes the slightest damage to the building [or motor vehicle]. -

Cap. 16 Tanzania Penal Code Chapter 16 of the Laws

CAP. 16 TANZANIA PENAL CODE CHAPTER 16 OF THE LAWS (REVISED) (PRINCIPAL LEGISLATION) [Issued Under Cap. 1, s. 18] 1981 PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER, DARES SALAAM Penal Code [CAP. 16 CHAPTER 16 PENAL CODE Arrangement of Sections PARTI General Provisions CHAPTER I Preliminary 1. Short title. 2. Its operation in lieu of the Indian Penal Code. 3. Saving of certain laws. CHAPTER II Interpretation 4. General rule of construction. 5. Interpretation. CHAPTER III Territorial Application of Code 6. Extent of jurisdiction of local courts. 7. Offences committed partly within and partly beyond the jurisdiction, CHAPTER IV General Rules as to Criminal Responsibility 8. Ignorance of law. 9. Bona fide claim of right. 10. Intention and motive. 11. Mistake of fact. 12. Presumption of sanity^ 13. Insanity. 14. Intoxication. 15. Immature age. 16. Judicial officers. 17. Compulsion. 18. Defence of person or property. 18A. The right of defence. 18B. Use of force in defence. 18C. When the right of defence extends to causing abath. 19. Use of force in effecting arrest. 20. Compulsion by husband. 21. Persons not to be punished twice for the same offence. 4 CAP. 16] Penal Code CHAPTER V Parties to Offences 22. Principal offenders. 23. Joint offences. 24. Councelling to commit an offence. CHAPTER VI Punishments 25. Different kinds of punishment. 26. Sentence of death. 27: Imprisonment. 28. Corpora] punishment. 29. Fines. 30. Forfeiture. 31. Compensation. 32. Costs. 33. Security for keeping the peace. 34. [Repealed]. 35. General punishment for misdemeanours. 36. Sentences cumulative, unless otherwise ordered. 37. Escaped convicts to serve unexpired sentences when recap- 38. -

View the Slip Opinion(S)

FILED AUGUST 14, 2018 In the Office of the Clerk of Court WA State Court of Appeals, Division III IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON DIVISION THREE STATE OF WASHINGTON, ) ) No. 35295-1-III Respondent, ) ) v. ) ) BRYAN JACOB STORMS, ) UNPUBLISHED OPINION ) Appellant. ) FEARING, J. — This appeal requires us to address the prerogatives of the trial court when resentencing an offender on directions from the Court of Appeals when an error occurred in the initial sentence. We hold that the trial court did not engage in vindictiveness when resentencing appellant Bryan Storms and that Storms’ sentencing counsel did not engage in ineffective assistance of counsel when advocating during resentencing. Therefore, we affirm the sentence imposed by the trial court during remand. FACTS On February 10, 2013, Bryan Storms sped from a pursuing police officer. State v. Storms, No. 32653-5-III (Wash. Ct. App. Jan. 31, 2017) (unpublished), http://www.courts.wa.gov/opinions/pdf/326535_unp.pdf. Storms ran through a stop sign in his Honda Civic, smashed into a pickup truck, and sent the truck into the air before it No. 35295-1-III State v. Storms struck a telephone pole. The driver of the pickup truck died at the scene. Storms’ two passengers, Ron Martel and Lynn Blumer, suffered injuries. Storms fled the collision scene on foot. PROCEDURE The State of Washington charged Bryan Storms with vehicular homicide, two counts of vehicular assault, failure to remain at the scene of an accident-fatality (hit and run) and third degree driving while license suspended. Vehicular homicide, under RCW 46.61.520, constitutes a three alternative means crime. -

Police Officers Should Know About Arson

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. -'. ~. ~.! .• !",'""' of . / .... t.,,',~ - '.- .- .., " -. -~,What police officers should know about arson ., ", " .. ' ' NCJRS FEB 91979 ACQUISIT!ONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction . .. 2 The iceberg crime. Common arson myths. Apathy ...and how to combat it. The police officer's role. 1. What to look for: motives ...................... 6 Establishing a motive. Rational and irrational motives. Burning for profit: some signs. Spite, "cause" and cover-up fires. How pyromaniacs and juvenile arsonists operate. 2. Interviews: who and how .. , .................... 12 Firemen, owners and other good people to talk to. Checking the records. In terviewing techniques and how to handle suspects. Protection of physical evidence. 3. Arrest and trial ............................... 18 Motive plus opportunity equals suspect. Narrowing the / list. Evidence: direct and circumstantial. 4. How to get more training ....................... 20 Seminars and courses. The officer's stake in curbing arson. What police officers should know loss of income to these employees and loss of tax income to the community." about arson Why? Perhaps people have been conditioned to think of fire as some thing that's just bound to happen once in a while, and worrying about what made one happen is a little like locking the barn door after the prize bull has Arson is the iceberg crime-its mention in the police loos and fire escaped. Or perhaps it's because of a records of our nation represents only a tip visible above tl~e surface. seemingly widespread public attitude It is a crime believed to be much more prevalent than statistics would that arson is pretty much confined to indicate.