Uneasy Negotiations: Urban Redevelopment, Neoliberalism and Hindu Nationalist Politics in Ahmedabad, India Renu Desai (Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish Diversity of the Vatrak Stream, Sabarmati River System, Rajasthan

Rec. zool. Surv. India: Vol. 117(3)/ 214-220, 2017 ISSN (Online) : (Applied for) DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v117/i3/2017/120965 ISSN (Print) : 0375-1511 Fish diversity of the Vatrak stream, Sabarmati River system, Rajasthan Harinder Singh Banyal* and Sanjeev Kumar Desert Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, Jodhpur – 342005, Rajasthan, India; [email protected] Abstract Five species of fishes belonging to order cypriniformes from Vatrak stream of Rajasthan has been described. Taxonomic detailsKeywords along: with ecology of the fish fauna and stream morphology are also discussed. Diversity, Fish, Rajasthan, stream morphology, Vatrak Introduction Sei joins from right. Sabarmati River originates from Aravalli hills near village Tepur in Udaipur district of Rajasthan, the biggest state in India is well known for its Rajasthan and flows for 371 km before finally merging diverse topography. The state of Rajasthan can be divided with the Arabian Sea. Thus the Basin of Sabarmati River into the following geographical regions viz.: western and encompasses states of Rajasthan and Gujarat covering north western region, well known for the Thar Desert; the an area of 21,674 Sq.km between 70°58’ to 73°51’ East eastern region famous for the Aravalli hills, whereas, the longitudes and 22°15’ to 24°47’ North latitudes. The southern part of the state with its stony landscape offers Vatrak stream basin is circumscribed by Aravalli hills typical sites for water resource development where most on the north and north-east, Rann of Kachchh on the of the man-made reservoirs are present. Mahi River basin west and Gulf of Khambhat on the south. -

Disastrous Condition of the Sabarmati River

PRESS RELEASE 27 March 2019 Disastrous Condition of the Sabarmati River - Release of report on joint investigations by Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti and Gujarat Pollution Control Board, of the pollution levels in the prime water source of Ahmedabad District. The Sabarmati River in the Ahmedabad City stretch, before the Riverfront, is dry and within the Riverfront Project stretch, is Brimming with Stagnant Water. In the last 120 kilometres, before meeting the Arabian Sea, it dead comprises of just industrial effluent and sewage. On 12 March 2019, the Regional Officers Mr Tushar Shah and Ms Nehalben Ajmera of Gujarat Pollution Control Board, Rohit Prajapati and Krishnakant of Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti, Social Activist Mudita Vidrohi of Ahmedabad, Subodh Parmar, Lawyer of Gujarat High Court, conducted a joint investigation. This was conducted in the context of implementation of the Order, dated 22.02.2017, of the Supreme Court in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 375 of 2012 (Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti & Anr V/s Union of India & Ors) about the status of industrial effluent and sewerage discharge into the Sabarmati River stretch of Ahmedabad District. The investigation reports are shocking and reveal the disastrous condition of Sabarmati River in and around Ahmedabad District and about 120 kilometres downstream. Sabarmati River no longer has any fresh water when it enters the city of Ahmedabad. The Sabarmati Riverfront has merely become a pool of polluted stagnant water while the river, downstream of the riverfront, has been reduced to a channel carrying effluents from industries from Naroda, Odhav Vatva, Narol and sewerage from Ahmedabad city. The drought like condition of the Sabarmati River intensified by the Riverfront Development has resulted in poor groundwater recharge and increased dependency on the already ailing Narmada River. -

(PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat

ROADS AND BUILDINGS DEPARTMENT (PANCHAYAT) Government of Gujarat ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) FOR GUJARAT RURAL ROADS (MMGSY) PROJECT Under AIIB Loan Assistance May 2017 LEA Associates South Asia Pvt. Ltd., India Roads & Buildings Department (Panchayat), Environmental and Social Impact Government of Gujarat Assessment (ESIA) Report Table of Content 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 MUKHYA MANTRI GRAM SADAK YOJANA ................................................................ 1 1.3 SOCIO-CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT: GUJARAT .................................... 3 1.3.1 Population Profile ........................................................................................ 5 1.3.2 Social Characteristics ................................................................................... 5 1.3.3 Distribution of Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Population ................. 5 1.3.4 Notified Tribes in Gujarat ............................................................................ 5 1.3.5 Primitive Tribal Groups ............................................................................... 6 1.3.6 Agriculture Base .......................................................................................... 6 1.3.7 Land use Pattern in Gujarat ......................................................................... -

(Gujarati to English Translation of Gog Resolution) the Appointment of Members for Gujarat State Commission for Protection of Child Rights - Gandhinagar

(Gujarati to English Translation of GoG Resolution) The Appointment of members for Gujarat State Commission for Protection of Child Rights - Gandhinagar Government of Gujarat Social Justice and Empowerment Department, Notification No.: JJA-102013-26699-CH Secretariat, Gandhinagar, Date : 21-2-2013 Notification Commission for protection of child rights act 2005 (4th part 2006,) paragraph no. 17, this department notification no JJA/10/2012/223154/CH, dated 28/9/2013 The Gujarat State Commission for Protection of Child Rights has been formed. As per act Section-18 following are the appointed as the members of the commission: Sr. No. Name of Members Address 1 Dr. Naynaben J. Ramani Shivang, Ambavadi. Opp. Garden, Nr.Sarwoday High School, Keshod, District. Junagadh 2 Ms. Rasilaben Sojitra Akansha, 1 Udaynagar, Street No.13, Madhudi Main Road, Jetpur, District – Rajkot 3 Ms. Bhartiben Virsanbhai Tadavi Raghuvirshing Colony, Palace Road, Rajpipada, District – Narmada. 4 Ms. Madhuben Vishnubhai Senama Parmar Pura, Nr. Sefali Cinema, Kadi, District - Mahesana 5 Ms.Jignaben Sanjaykumar Pandya Shraddha – 2, Vardhaman Colony, Nr. Vachali Fatak, Surendranagar. 6 Ms. Hemkashiben Manojbhai Chauhan At - Limbasi, Taluka – Matar District - Kheda Letter : PRC.122013/579/V.2 Education Department Secretariat, Gandhinagar Date:07/3/2013 A copy sent for the information and necessary proceedings. - All Heads of Department occupied Education Department (J.G. Rana) Term of the Members of Commissions for Protection of Child Rights Act 2005 (part 4th, 2006) of Section -19 is for three years from the date of joining as a member. By order and in the name of the Governor of Gujarat. Sd/- (J.P.Nayi) Under Secretary, Social Justice and Empowerment Department To - The Principal Secretary to the Hon. -

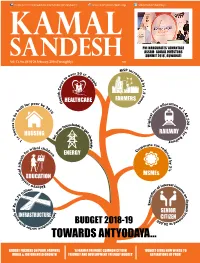

Amit Shah at Parivartan Yatra Rally in Mysore

https://www.facebook.com/Kamal.Sandesh/ www.kamalsandesh.org @kamalsandeshbjp PM INAUGURAtes ‘ADVANTAGE ASSAM- GLOBAL INVESTORS SUMMit 2018’, GUWAHATI Vol. 13, No. 04 16-28 February, 2018 (Fortnightly) `20 HEALTHCARE FARMERS HOUSING RAILWAY ENERGY MSMEs EDUCATION SENIOR INFRASTRUCTURE BUDGET 2018-19 CITIZEN TOWARDS ANTYODAYA... BUDGET FOCUSES ON POOR, FARMERS ‘A FARMER FRIENDLY, COMMON CITIZEN ‘BUDGET GIVES NEW WINGS TO RURAL & JOB ORIENTED GROWTH FRIENDLY AND DEVELOPMENT FRIENDLY BUDGEt’ 16-28 FEBRUARY,ASP IRATIONS2018 I KAMAL OF P SANDESHoor’ I 1 Karnataka BJP welcomes BJP National President Shri Amit Shah at Parivartan Yatra Rally in Mysore. BJP National President Shri Amit Shah hoisting the tri-colour on the 69th Republic Day celebration at BJP HQ, New Delhi. BJP National President Shri Amit Shah paying floral tributes Shri Amit Shah addressing the SARBANSDANI to to Sant Ravidas ji on his Jayanti at BJP H.Q. in New Delhi commemorate the 350th birth anniversary of Guru Gobind 2 I KAMAL SANDESH I 16-28 FEBRUARY, 2018 Singh ji at Chandani Chowk, New Delhi. Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Mukesh Kumar Phone +91(11) 23381428 FAX +91(11) 23387887 BUDGET FOCUSES ON POOR, FARMERS RURAL & JOB E-mail ORIENTED GROWTH [email protected] Finance Minister Shri Arun Jaitley presented on February 1, 2018 general [email protected] 06 Budget 2018-19 in Parliament. It was second time the budget was Website: www.kamalsandesh.org presented on first of February instead following colonial era practices of... VAICHARIKI 17 C M SIDDARAMAIAH SYNONYMOUS WITH Aspects of Economics 21 CORRUPTION: AMIT SHAH BJP National President Shri SHRADHANJALI Amit Shah said Karnataka CM Siddaramaiah was synonymous Chintaman Vanga / Hukum Singh 23 with corruption and added 15 CONGRESS GOVERNMENT that the state government was ARTICLE IN KARNATAKA IS ON EXIT protecting the killers of Hindu.. -

Scheme for Incentive to Industries Preamble One of the Leading Industrial States. Government of Gujarat Has Announced an The

Guiarat Industrial Policy 2015 - Scheme for Incentive to Industries Government of Guiarat Industries & Mines Department Resolution No.INC-10201 5-645918-I Sachivalaya, Gandhinagar Dated: 25/07 /20L6 Read: Industrial Policy 2015 of Government of Gujarat Preamble Gujarat has always been at the forefront of economic growth in the country. It is one of the leading industrial states. Government of Gujarat has announced an ambitious Industrial Poliry 2015, in lanuary 2015, with the objective of creating a healthy and conducive climate for conducting business and augmenting the industrial development of the state. The Industrial Poliry has been framed with the broad idea of enhancing industrial growth that empowers people and creates employment, and establishes a roadmap for improving the state's ability to facilitate business. Gujarat's development vision will continue to emphasize on integrated and sustainable development, employment generation, opportunities for youth, increased production and inclusive growth. Make in India is a prestigious program of Government of India. The Industrial Poliry 2015 ofthe Government of Gujarat envisages a focused approach on the Make in India program as the state's strategy for achieving growth. Gujarat is a national leader in 15 of the 25 sectors identified under the Make in India program, and is also focusing on 6 more sectors. Thus, with a strong base in 21 out of the 25 sectors under Make in India, Gujarat can take strong leadership in this prestigious program of the Government of India. The Industrial Policy 2015 aims to encourage the manufacturing sector to upgrade itself to imbibe cutting edge technology and adopt innovative methods to significantly add value, create new products and command a niche position in the national and international markets. -

The Spectre of SARS-Cov-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: a Tale of Two Cities

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . The Spectre of SARS-CoV-2 in the Ambient Urban Natural Water in Ahmedabad and Guwahati: A Tale of Two Cities Manish Kumar1,2*, Payal Mazumder3, Jyoti Prakash Deka4, Vaibhav Srivastava1, Chandan Mahanta5, Ritusmita Goswami6, Shilangi Gupta7, Madhvi Joshi7, AL. Ramanathan8 1Discipline of Earth Science, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 355, India 2Kiran C Patel Centre for Sustainable Development, Indian Institute of Technology Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 3Centre for the Environment, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 4Discipline of Environmental Sciences, Gauhati Commerce College, Guwahati, Assam 781021, India 5Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam 781039, India 6Tata Institute of Social Science, Guwahati, Assam 781012, India 7Gujarat Biotechnology Research Centre (GBRC), Sector- 11, Gandhinagar, Gujarat 382 011, India 8School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India *Corresponding Author: [email protected]; [email protected] Manish Kumar | Ph.D, FRSC, JSPS, WARI+91 863-814-7602 | Discipline of Earth Science | IIT Gandhinagar | India 1 NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.12.21258829; this version posted June 16, 2021. -

Daily Economic News Summary: 20 February 2018

Daily Economic News Summary: 20 February, 2018 Daily Economic News Summary: 20 February 2018 1. Maharashtra Signs MOUs worth Rs4.8 Trillion at Magnetic Maharashtra Summit Source: Livemint (Link) Maharashtra signed investment commitments worth around Rs4.85 trillion with a number of global and domestic companies on Feb 19, the second day of the Magnetic Maharashtra Global Investors Summit. Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis said the state was likely to exceed its target of signing memoranda of understanding (MoUs) worth Rs10 trillion. Ahead of the three-day summit, the state had set a target of signing nearly 4,000 MoUs that would create 3.5 million jobs. On Feb 19, the state entered into 36 agreements which would create around 2.9 million jobs. The MoUs signed on Feb 19 include one between the Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority (PMRDA) and Virgin Hyperloop One (Virgin Group) to develop hyperloop connectivity between Mumbai and Pune at an investment of Rs40,000 crore, creating 13,000 jobs. 2. Donald Trump Jr to Visit India Today, Indo-Pacific Ties, Realty Projects on Agenda Source: Business Standard (Link) The executive vice-director of Trump Organisation is scheduled to arrive in India on his maiden visit on Feb 19. During the week-long trip, Donald Trump Jr. will not only endorse his luxurious residential project-Trump Towers, but he is scheduled to deliver a speech on foreign policy in India. Trump Jr. will meet with Indian investors and business leaders in Kolkata, Mumbai, Pune and Gurgaon respectively, The Washington Post reported. According to business partners in India, many units in the Trump Towers are selling about 30 percent per square foot higher than the current market rates. -

In This Issue... Plus

Volume 18 No. 2 February 2009 12 in this issue... 6 Vibrant Gujarat 8 India Inc. at Davos 12 15th Partnership Summit 22 3rd Sustainability Summit 8 31 Defence Industry Seminar plus... n India Rubber Expo 2009 n The Power of Cause & Effect n India’s Tryst with Corporate Governance 22 n India & the World n Regional Round Up n And all our regular features We welcome your feedback and suggestions. Do write to us at 31 [email protected] Edited, printed and published by Director General, CII on behalf of Confederation of Indian Industry from The Mantosh Sondhi Centre, 23, Institutional Area, Lodi Road, New Delhi-110003 Tel: 91-11-24629994-7 Fax: 91-11-24626149 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cii.in Printed at Aegean Offset Printers F-17 Mayapuri Industrial Area, Phase II, New Delhi-110064 Registration No. 34541/79 JOURNAL OF THE Confederation OF INDIAN INDUSTRY 2 | February 2009 Communiqué Padma Vibhushan award winner Ashok S Ganguly Member, Prime Minister’s Council on Trade & Industry, Member India USA CEO Council, Member, Investment Commission, and Member, National Knowledge Commission Padma Bhushan award winners Shekhar Gupta A M Naik Sam Pitroda C K Prahalad Editor-in-Chief, Indian Chairman and Chairman, National Paul and Ruth McCracken Express Newspapers Managing Director, Knowledge Commission Distinguished University (Mumbai) Ltd. Larsen & Toubro Professor of Strategy Padma Shri award winner R K Krishnakumar Director, Tata Sons, Chairman, Tata Coffee & Asian Coffee, and Vice-Chairman, Tata Tea & Indian Hotels Communiqué February 2009 | 5 newsmaker event 4th Biennial Global Narendra Modi, Chief Minister, Gujarat, Mukesh Ambani, Chairman, Investors’ Summit 2009 Reliance Industries, Ratan Tata, Chairman, Tata Group, K V Kamath, President, CII, and Raila Amolo Odinga, Prime Minister, Kenya ibrant Gujarat, the 4th biennial Global Investors’ and Mr Ajit Gulabchand, Chairman & Managing Director, Summit 2009 brought together business leaders, Hindustan Construction Company Ltd, among several investors, corporations, thought leaders, policy other dignitaries. -

Gujarat Council of Primary Education DPEP - SSA * Gandhinagar - Gujarat

♦ V V V V V V V V V V V V SorVQ Shiksha A b h i y O f | | «klk O f^ » «»fiaicfi ca£k ^ Annual Work Plan and V** Budget Year 2005-06 Dist. Rajkot Gujarat Council of Primary Education DPEP - SSA * Gandhinagar - Gujarat <* • > < « < ♦ < » *1* «♦» <♦ <♦ ♦♦♦ *> < ♦ *1* K* Index District - Rajkot Chapter Description Page. No. No. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Process of Plan Formulation 5 Chapter 3 District Profile 6 Chapter 4 Educational Scenario 10 Chapter 5 Progress Made so far 26 Chapter 6 Problems and Issues 31 Chapter 7 Strategies and Interventions 33 Chapter 8 Civil Works 36 Chapter 9 Girls Education 59 Chapter 10 Special Focus Group 63 Chapter 11 Management Information System 65 Chapter 12 Convergence and Linkages 66 Budget 68 INTRODUCTION GENERAL The state of Gujarat comprises of 25 districts. Prior to independence, tiie state comprised of 222 small and big kingdoms. After independence, kings were ruling over various princely states. Late Shri Vallabhbhai Patel, the than Honorable Home Minister of Government of India united all these small kingdoms into Gujarat-Bombay state (Bilingual State) during 1956. In accordance with the provision of the above-mentioned Act, the state of Gujarat was formed on 1 of May, 1960. Rajkot remained the capital of Saurashtra during 1948 to 1956. This city is known as industrial capital of Saurashtra and Kutch region. Rajkot district can be divided into three revenue regions with reference to geography of the district as follow: GUJARAT, k o t ¥ (1) Rajkot Region:- Rajkot, Kotda, Sangani, Jasdan and Lodhika blocks. -

Sabarmati Riverfront Development: an Exercise in 'High-Modernism'?

I.S.RIVERS 2018 Sabarmati Riverfront Development: An Exercise in ‘High-Modernism’? A la reconquête des berges du fleuve Sabarmati : un exercice de "haut-modernisme" ? Krishnachandran Balakrishnan Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Bangalore, India ([email protected]) RÉSUMÉ En utilisant l’exemple de l’aménagement des berges du fleuve Sabarmati (Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project - SRDP) à Ahmedabad, cet article illustre comment la catégorie conceptuelle de berge, déjà présente plus particulièrement à Londres et Paris, a inspiré l’imagination de ce que devrait être une rivière urbaine en Inde. Cet article s’attache à revoir l’étendue du projet pour conformer une rivière alimentée par la mousson à la catégorie conceptuelle prédéfinie de berge. L'argumentaire développé dans l’article est que le SRDP peut être vu comme une illustration de haut-modernisme comme l’indique James Scott – à la fois en termes d’ordre visuel qu’il s’efforce de créer et en termes de recours au concept simpliste d’écologie et d’hydrologie des rivières. Cet article conclut avec une discussion sur l’utilité des professionnels de la conception architecturale, urbaine et paysagère de comprendre les spécificités locales des écosystèmes et sociétés et d’utiliser le design comme un processus capable d’aller au-delà des catégories spatiales et conceptuelles simplistes. ABSTRACT Using the case of the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project (SRDP) in Ahmedabad, this paper illustrates how the conceptual category of the ‘riverfront’, as seen in London and Paris in particular, has shaped the imagination of what an urban river ‘should’ be in India. The paper examines the lengths to which the project goes to fit a monsoon fed river-scape into this predefined conceptual category of a ‘riverfront’. -

Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project

SABARMATI RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT A Multidimensional Environmental Improvement and Urban Rejuvenation Project … one of the most innovative projects towards urban regeneration in the world to make the city livable & sustainable (KPMG ) SABARMATI RIVER and AHMEDABAD The River Sabarmati flows from north to south splitting Ahmedabad into almost two equal parts. For many years, it has served as a water source and provided almost no formal recreational space for the city. As the city has grown, the Sabarmati river had been abused and neglected and with the increased pollution was posing a major health and environmental hazard to the city. The slums on the riverbank were disastrously flood prone and lack basic infrastructure services. The River became back of the City and inaccessible to the public Ahmedabad and the Sabarmati :1672 Sabarmati and the Growth of Ahmedabad Sabarmati has always been important to Ahmedabad As a source for drinking water As a place for recreation As a place to gather Place for the poor to build their hutments Place for washing and drying clothes Place for holding the traditional Market And yet, Sabarmati was abused and neglected Sabarmati became a place Abuse of the River to dump garbage • Due to increase in urban pressures, carrying capacity of existing sewage system falling short and its diversion into storm water system releasing sewage into the River. Storm water drains spewed untreated sewage into the river • Illegal sewage connections in the storm water drains • Open defecation from the near by human settlements spread over the entire length. • Discharge of industrial effluent through Nallas brought sewage into some SWDs.