A Half Century of Service John R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0506Wbbmg011906.Pdf

2005-06 OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY BasketballLADY MONARCH 1992 Fourteen-Time CAA Champions 1993 Table of Contents 1994 Media Information ................................................................................................... 2-3 Travel Plans .................................................................................................................. 4 The Staff 1995 Head Coach Wendy Larry ....................................................................................... 6-8 Assistant Coaches ................................................................................................... 9-12 Support Staff/Managers ...................................................................................... 13-14 1996 Meet the Lady Monarchs 2005-06 Outlook .................................................................................................... 16-17 Player Bios ............................................................................................................. 18-37 1997 Rosters .........................................................................................................................38 A Closer Look at Old Dominion This is Norfolk/Hampton Roads ....................................................................... 40-41 1998 Old Dominion University ................................................................................... 42-43 Administration/Academic Support .................................................................. 44-46 Athletic Facilities ...................................................................................................... -

Records and History

Records and History Old Dominion University Baseball 2009 Old Dominion University Baseball 2009 27 BUD METHENY n Jan 2, 2003 Old Dominion University and the athletic program lost a legend with the passing of Bud MethenyO and his wife Fran on the same day. Bud spent 32 years at the University from 1948 to 1980 as an instructor, basketball coach, athletic director and coach of the baseball program. Baseball was his passion, and where he made his mark. As a member of the New York Yankees from 1937 to 1946, Bud played on the 1943 World Series championship squad that stopped St. Louis. Bud started for the Yankees in the second and last game of the series. As a coach of the Monarchs, he rolled up a 423‑363‑6 record and was honored by the NCAA as the Eastern Regional coach of the year in 1963 and ‘64 and National Coach Of the Year in 1964. His Monarchs won the NCAA College Division Eastern Regional championship in 1963 and 1964 and took second in 1965. Bud not only coached baseball, but he was the men’s basketball head coach from 1948‑1965, compiling a 198‑163 record and posting 16 winning seasons. He served as the University’s athletic director from 1963‑1970. Following his retirement it was only fitting to honor Bud with the naming of the new baseball stadium in 1983 and with the adoption of the blue and white pin stripes of the Yankees on uniforms the following year, which coincides with the University’s new school colors, adopted in 1986. -

Lady Monarch Schedule Meet the Lady Monarchs

H DD YY AA RR CC H LL AA MM OO NN GG aa mm ee DD aa yy NN oo tt ee ss 2003-04 LADY MONARCH SCHEDULE MEET THE LADY MONARCHS November…………………………………………….. 2-2 Overall, 1-0 Colonial Athletic Association 4 Tue. BASKETBALL TRAVELERS (EHB) W, 81-68 Today’s Game: Charlotte (Game Four) 11 Tue. TEAM CONCEPT (EXB) . .L, 68-81 Ted Constant Center * Norfolk, VA* 1:00 p.m. 14-15 WBCA PRESEASON CLASSIC POSSIBLE STARTING LINE-UP: 14 Fri. at #20 Colorado . .L, 67-84 Pos. No. Name: Cl: Ht: Stats: Misc: 15 Sat. vs. #22 Auburn . .L, 49-84 F 04 Myriah Spence Sr. 6-0 10.8 ppg 4.3 rpg Shooting .5000 from the field F 23 Monique Coker Sr. 6-1 16.8 ppg 6.8 rpg 26 pts - career high vs. PSU 21 Fri. at William & Mary * . .W, 75-58 G 01 Max Nhassengo Sr. 5-10 8.5 ppg 4.8 rpg 15 pts, 7-8 from line vs. PSU 25 Tue. #7 PENN STATE . .W, 75-68 G 03 Lawona Davis Fr. 5-11 6.5 ppg 3.8 rpg Career-high 17 pts. against Tribe 30 Sun. CHARLOTTE . .1:00 p.m. G 24 Shareese Grant Jr. 5-8 17.0 ppg 0.5 rpg Leading scorer in 3 of 4 games December…………………………………………….. OFF THE BENCH: 3 Wed. at Virginia Tech . .7:00 p.m. Pos. No. Name: Cl: Ht: Stats: 7 Sun. NORTH CAROLINA . .2:00 p.m. G 12 Melea Caldwell Jr. 5-4 -- -- 15 Mon. -

2010-11 Opponents Game Kentucky Wildcats 1 Nov

2010-11 Opponents Game Kentucky Wildcats 1 Nov. 12 in Lexington, Ky. | 11 a.m. Location Lexington, Ky Enrollment 25,000 Colors Blue and White Nickname Wildcats Arena Memorial Coliseum Conference SEC President TBA Athletic Director Mitch Barnhart Head Coach Matthew Mitchell Alma Mater Mississippi State, 1995 Career Record 91-69 Matthew Mitchell Record at School 61-40 Head Coach Assistant Coaches Kyra Elzy, Matt Insell, Shalon Pillow 2009-10 Record 28-8 Conference Record 11-5 Media Relations Contact Susan Lax E-Mail [email protected] 30 Phone Game Notre Dame Fighting Irish 2 Nov. 15 in South Bend, Ind. | 7 p.m. Location Notre Dame, Ind. Enrollment 8,363 Colors Gold and Blue Nickname Fighting Irish Arena Purcell Pavilion at Joyce Center Conference Big East President Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C. Athletic Director Jack Swarbrick Head Coach Muffet McGraw Alma Mater St. Joseph’s Career Record 613-244 Muffet McGraw Record at School 525-203 Head Coach Assistant Coaches Jon Tsipsis, Carol Owens, Niele Ivey 2009-10 Record 29-6 Conference Record 12-4 Media Relations Contact Chris Masters E-Mail [email protected] Phone 574-631-8032 2010-11 Eagles Basketball Game Central Arkansas Bears 3 Nov. 19 in Morehead | 7 p.m. | Comfort Inn and Suites Classic Central Arkansas Location Conway, Ark. Enrollment 11,758 Colors Purple and Black Nickname Bears Arena Farris Center Conference Southland President Dr. Allen C. Meadors Athletic Director Dr. Brad Teague Head Coach Matt Daniel Alma Mater Harding, 1998 Career Record 27-31 Matt Daniel Record at School 27-31 Head Coach Assistant Coaches Tony Kemper, Caronica Randle, Tiffany Brooks 2009-10 Record 21-8 Conference Record 11-5 Media Relations Contact Josh Goff E-Mail [email protected] Phone 501-540-5695 31 Game Houston Baptist Huskies 4 Nov. -

Oral History Interview with ARTHUR B. METHENY Norfolk, Virginia May 29, 1975 by James R

Oral History Interview with ARTHUR B. METHENY Norfolk, Virginia May 29, 1975 by James R. Sweeney, Old Dominion University Sweeney: Today we’re continuing the interview with Mr. Arthur B. "Bud" Metheny, for many years the baseball coach and former chairman of the department of health and physical education at Old Dominion University. Starting with question 111 here, by 1964 you seemed in public statements to see a change for the better coming in the college’s athletic policy as plans were being formulated for a new physical education building with a 10,000 seat gymnasium. You also indicated a possible change in the school’s "no athletic scholarships" policy. I wonder why such changes came about in the administration’s attitude? Metheny: Well, in 1960 I wrote the first letter investigating the possibility of having our new building. And it took us 10 years to get it. We got in it in 1970. And we were doing well in baseball, and the students wanted to move up in the grading of the entire program. That was their request, and in the editorials in the newspaper and things of that type. And so we started investigating the possibility of moving up in athletics, which we did in getting into the Mason— Dixon. And with the demand of the newspapers and the public we thought that we were about ready to move up in the field of athletics. So we started making our preparations for that. And we knew that if we did move up and to be able to compete on an equal basis that we’d have to give athletic scholarships. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS All-America Teams 2 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 20 Other Honors 22 First Team All-Americans By School 25 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 34 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 39 ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1980 Denise Curry, UCLA; Tina Division II Carla Eades, Central Mo.; Gunn, BYU; Pam Kelly, Francine Perry, Quinnipiac; WBCA COACHES’ Louisiana Tech; Nancy Stacey Cunningham, First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Lieberman, Old Dominion; Shippensburg; Claudia Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Inge Nissen, Old Dominion; Schleyer, Abilene Christian; by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Jill Rankin, Tennessee; Lorena Legarde, Portland; Farm through 2010-11. Susan Taylor, Valdosta St.; Janice Washington, Valdosta Rosie Walker, SFA; Holly St.; Donna Burks, Dayton; 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Warlick, Tennessee; Lynette Beth Couture, Erskine; Baptist; Marianne Crawford, Woodard, Kansas. Candy Crosby, Northern Ill.; Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, 1981 Denise Curry, UCLA; Anne Kelli Litsch, Southwestern Cal St. Fullerton; Lusia Donovan, Old Dominion; Okla. Harris, Delta St.; Jan Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech; Division III Evelyn Oquendo, Salem St.; Irby, William Penn; Ann Kris Kirchner, Rutgers; Kaye Cross, Colby; Sallie Meyers, UCLA; Brenda Carol Menken, Oregon St.; Maxwell, Kean; Page Lutz, Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Cindy Noble, Tennessee; Elizabethtown; Deanna Debbie Oing, Indiana; Sue LaTaunya Pollard, Long Kyle, Wilkes; Laurie Sankey, Rojcewicz, Southern Conn. Beach St.; Bev Smith, Simpson; Eva Marie St.; Susan Yow, Elon. Oregon; Valerie Walker, Pittman, St. Andrews; Lois 1976 Carol Blazejowski, Montclair Cheyney; Lynette Woodard, Salto, New Rochelle; Sally St.; Cindy Brogdon, Mercer; Kansas. -

1 Lady Raider Basketball 2002-03 MISSION STATEMENT

Table of Contents . 1 2000-01 REVIEW . 49-66 2002-03 Roster . 2 Review . 50 GENERAL INFORMATION 2002-03 Radio/TV Roster . 3 Season Stats . 51 Location . Murfreesboro, Tenn. Media Information . 4-5 Results/Leaders . 52 Enrollment . 21,163 MT Media Relations . 4 Game-by-Game . 53 Founded . 1911 Lady Raider Network . 6 Miscellaneous Stats . 54 Nickname . Lady Raiders 2002-03 Travel Plans . 6 Team Highs/Lows . 55-56 Colors . Royal Blue and White NCAA Tourney Bracket . 7 Starters/Points-Rebounds-Assists . 57 President . Dr. Sidney A. McPhee Murphy Center . 8 Sun Belt Stats . 58-61 Athletic Director . Boots Donnelly Box Scores . 62-66 SWA . Diane Turnham COACHES AND PLAYERS . 9-34 Athletics Phone . 615/898-2450 Head Coach Stephany Smith . 10-11 MT HISTORY . 67-104 Website . GoBlueRaiders.com Assistant Coach Melanie Walls . 12 Hall of Fame . 68 Conference . Sun Belt Assistant Coach Jennifer Grandstaff . 13 Letterwinners . 69 Home Court . Murphy Center Assistant Coach Kelly Chastain . 14 All-Conference Performers . 70 Director of Basketball Oper. Kate Sullivan . 15 Players of the Week . 71 MEDIA RELATIONS Support Staff . 15 Statistical Leaders . 72 Director . .Mark Owens 2002-03 Season Preview . 16-18 All-Time Series . 73 Assistant . Ryan Simmons Sophomore Tiffany Fisher . 19 All-Time Series Results . 74-77 Assistant/WBB Contact . Denise Gideon Sophomore Ciara Gray . 20 Individual Career Records . 78-79 Assistant . Jo Jo Freeman Sophomore Patrice Holmes . 21 Individual Season Records . 80 Gideons e-mail . [email protected] Junior Jennifer Justice . 22 Individual Game Records . 81 Sophomore Eboni Kirby . 23 Gideon’s Office Phone . 615/904-8115 Records By Class . -

Pre-Ncaa Women's Basketball Records

PRE-NCAA WOMEN’S BASKETBALL RECORDS Pre-NCAA Statistical Leaders 2 AIAW Results 5 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS The following women played all or most of their collegiate careers before the Player, Team Seasons G Pts. era of official NCAA women’s basketball statistics, which began in 1981-82. Queen Brumfield, Southeastern La. 1976-79 133 2,986 Before becoming members of the NCAA in 1981-82, most women’s programs Lusia Harris, Delta St. 1974-77 115 2,981 were under the auspices of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW). Pam Kelly, Louisiana Tech 1979-82 153 2,979 Wanda Hightower, UAB 1979-82 111 2,855 The NCAA would like to thank the University of Maryland libraries for their Jill Rankin, Wayland Baptist/Tennessee 1977-79, 80 146 2,851 assistance in sharing the AIAW Archive information: Betty Booker, Memphis 1977-80 137 2,835 “AIAW Archives, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.” Valerie Still, Kentucky 1980-83 119 2,763 If you have information that can be utilized in expanding/completing any por- Tina Gunn, BYU 1977-80 101 2,759 tion of this section, please send supporting documents to ncaastats@ncaa. Kathy Miller, Weber St. 1976-79 100 2,746 org. Anne Donovan, Old Dominion 1980-83 136 2,719 Cindy Stumph, Weber St. 1980-83 122 2,690 Ann Meyers, Dayton 1977-80 126 2,672 Inge Nissen, Old Dominion 1977-80 135 2,647 Jerilyn Harper, Tennessee/Tennessee Tech 1979, 80-82 129 2,603 CAREER RECORDS Anne Gregory, Fordham 1977-80 127 2,548 Sharon Upshaw, Drake 1977-80 127 2,513 Scoring Average Julie Gross, LSU 1977-80 131 2,488 (Minimum 2,000 Points) Peggie Gillom, Mississippi 1977-80 144 2,486 Nancy Lieberman, Old Dominion 1977-80 134 2,430 Player, Team Seasons G FG FT Pts. -

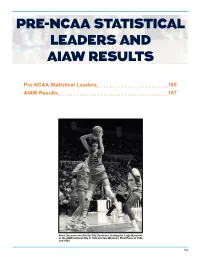

Pre-Ncaa Statistical Leaders and Aiaw Results

PRE-NCAA STATISTICAL LEADERS AND AIAW RESULTS Pre-NCAA Statistical Leaders 165 AIAW Results 167 Anne Donovan excelled for Old Dominion, leading the Lady Monarchs to the AIAW national title in 1980 and two Women’s Final Fours in 1982 and 1983. 164 PRE-NCAA STATISTICAL LEADERS The following women played all or most of their collegiate careers before the Player, Team Seasons G Pts. era of official NCAA women’s basketball statistics, which began in 1981-82. Before becoming members of the NCAA in 1981-82, most women’s programs Jill Rankin, Wayland Baptist/ 1977-79, 80 146 2,851 were under the auspices of the Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Tennessee Women. Betty Booker, Memphis 1977-80 137 2,835 Valerie Still, Kentucky 1980-83 119 2,763 The NCAA would like to thank the University of Maryland libraries for their assistance in sharing the AIAW Archive information: Tina Gunn, BYU 1977-80 101 2,759 Kathy Miller, Weber St. 1976-79 100 2,746 “AIAW Archives, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.” Anne Donovan, Old Dominion 1980-83 136 2,719 If you have information that can be used in expanding/completing any portion Cindy Stumph, Weber St. 1980-83 122 2,690 of this section, please send supporting documents to Rick Nixon at rnixon@ Ann Meyers, UCLA 1977-80 126 2,672 ncaa.org. Inge Nissen, Old Dominion 1977-80 135 2,647 Jerilyn Harper, Tennessee/Tennessee 1979, 80-82 129 2,603 Tech CAREER RECORDS Anne Gregory, Fordham 1977-80 127 2,548 Sharon Upshaw, Drake 1977-80 127 2,513 Julie Gross, LSU 1977-80 131 2,488 SCORING AVERAGE Peggie Gillom, Ole Miss 1977-80 144 2,486 (Minimum 2,000 points) Nancy Lieberman, Old Dominion 1977-80 134 2,430 Player, Team Seasons G FG FT Pts. -

NOTICE! the Exact Routqs by Which Parta of -Iand Are Now Attacking the Strpng

y» / ' / FACE TWELKI I'hc Wcalher TUESDAY,; Forecast ol li. S. tteaiber Unreal) Manchester Evening Herald Average Daily Clrcnlatioh Fnr the Month at April. 1S44 Considerable cloudiness with Girls Scouts of ’Troop 12 will on the activities of the carnival s(-attered light showers and,/little About Town I omit their meeting this evening. committee on the annual event in Famous Director rhangein. Iem|icrature tonight and K of C Honors the Week before Labor day and a Fire Menaces ■t 8,746 Ittattrhrfitrr E iip itto H rralb Thnnday. ^ e Private Duty nurses will meeting Of this committee also Member of the Audit ,— III.— —— I called for Thursday evbnihg. British\ . and American hcM a Brilltary wMst thu jvei.lng Bureau at OIrealuttone . A a r iu C 'U / '. I Membcn of Helen Devldwon in tte Masonic Temple for the ReVe Tierney Cometlua Foley, ^ chairman of Ended by Rain Manchester— City of Village Charm^ Ijodfe, Daughtera at Vootia, will benefit o f the Memorial hospital. the communion breakfast commit *- War kelief meet this evening at T:M at. Cen Mrs. CaUerine Spencer and Mrs. tee, gave his final report on the (SIXTEEN PAGES) p k u ;e i'h k e e g e n t s ter and Foster ateets, and proceed Gladys Palmer are in charge of LfOcal Council Presenl.s affair and it was accepted. Woods and Grass vJSo (ClaaeUled AdvertlMag oa Page 14) MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAVt MAY 24, 1944 to the Watkins Funeral Home, in door and playing prises, Mrs. It was voted to drape the char II. -

Women's Basketball Award Winners

WOMEN’S BASKETBALL AWARD WINNERS Division I All-America Teams 2 Division II All-America Teams 9 Division III All-America Teams 11 National Award Winners 15 Coaching Awards 21 Other Honors 24 First Team All-Americans By School 27 First Team Academic All-Americans By School 37 NCAA Postgraduate Scholarship Winners By School 42 DIVISION I ALL-AMERICA TEAMS 1983 Anne Donovan, Old Dominion; Valerie Still, 1992 Shannon Cate, Montana; Dena Head, Kentucky; LaTaunya Pollard, Long Beach Tennessee; MaChelle Joseph, Purdue; WBCA St.; Paula McGee, Southern California; Rosemary Kosiorek, West Virginia; Tammi First selected in 1975. Voted on by the Wom en’s Cheryl Miller, Southern California; Janice Reiss, Virginia; Susan Robin son, Penn Basket ball Coaches Association. Was sponsored Lawrence, Louisiana Tech; Tanya Haave, St.; Frances Savage, Miami (FL); Dawn by Kodak through 2006-07 season and State Tennessee; Joyce Walker, LSU; Jasmina Staley, Virginia; Sheryl Swoopes, Texas Farm through 2010-11. Perazic, Mary land; Priscilla Gary, Kansas Tech; Val Whiting, Stanford. St. 1993 Andrea Congreaves, Mercer; Toni Foster, 1975 Carolyn Bush, Wayland Baptist; Marianne 1984 Pam McGee, Southern California; Cheryl Iowa; Lauretta Freeman, Auburn; Heidi Crawford, Immaculata; Nancy Dunkle, Cal Miller, Southern California; Janice Gillingham, Vanderbilt; Lisa Harrison, St. Fullerton; Lusia Harris, Delta St.; Jan Lawrence, Louisiana Tech; Yolanda Tennessee; Katie Smith, Ohio St.; Karen Irby, William Penn; Ann Meyers, UCLA; Laney, Cheyney; Tresa Brown, North Jennings, Nebraska; Sheryl Swoopes, Brenda Moeller, Wayland Baptist; Debbie Carolina; Janet Harris, Georgia; Becky Texas Tech; Milica Vukadinovic, California; Oing, Indiana; Sue Rojcewicz, Southern Jackson, Auburn; Annette Smith, Texas; Val Whiting, Stanford. -

9 6 Sports Divider

96 Sports Divider You should know our name. Not only that, you should know how athletically talented we were. The Lady Monarchs Lacrosse team was ranked nineth in the nation. Monarch Baseball and Lady Monarchs Basketball were ranked twenty-fifth in the nation. Both the men’s and the womens basketball team won the C M Championship. m siîp k f _ — __ Ik.-. Unless you were a hermit, you heard about the JBWL ■ i b »»»- ■ bkmSmmmSHhéH spectacular performance the Monarchs made in 0 0 w tr, w -laJS, « Pfhe N C M Tournament that made the nation say, “Wow!” The Villanova men’s basketball team fell prey to Monarch Power! Aside from the prestige o f national rankings, Monarch sports were fun to play and fun to watch. Jill Meitzer Sports Divider 'This might have been the most exciting and most thrilling basketball game I have ever been a part of," said Coach Jeff Capel. What thrilling and exciting game he is referring to, in case you might have missed it, was the triple overtime 89-91 upset of ninth ranked Villanova. With this win, the Monarchs went from underdog to dinner conversation. This win also advanced them to the sec ond round, marking the first time to the second round for the Monarchs since 1986. Unfortunately, the Mon archs fell to Tulsa, but they left the tournament with a lot of new fans. The Monarchs rolled into the NCAA Tournament after defeating George Mason 110-94, American 77-67 in overtime and James Madison 80-75. Defeating Madison earned them the CAA title.