Trade and Sustainable Land Management in Drylands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the United Nations Environment Programme to the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification at Its Eighth Session*

22 October 2007 ENGLISH ONLY UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION TO COMBAT DESERTIFICATION CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Eighth session Madrid, 3–14 September 2007 Report of the United Nations Environment Programme to the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification at its eighth session* I. Introduction 1. This report describes major activities of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) in support of the implementation of the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) for submission to the Conference of the Parties to the Convention at its eighth session. The report describes key UNEP activities and issues during the reporting period in areas relevant to the Convention. 2. UNEP advocates the view that decisions can and should be made not to change the desert but to live with it and preserve its resources for the future. The active participation of community groups in this task should include their taking charge of their own development, planning for risks and adapting to changing conditions while preserving their deep connections to these remarkable landscapes. The challenge remains to harness not only local but also global policy mechanisms and market incentives to develop a viable future for deserts through the achievement of both environmental conservation and economic development. The degradation of drylands is a growing problem that needs imaginative, collaborative and multi-sectoral action, since it is both a result of and a contributor to climate change, as well as a cause and consequence of poverty. II. World Environment Day 3. World Environment Day, commemorated each year on 5 June, is one of the principal vehicles through which the United Nations stimulates worldwide awareness of the environment and enhances political attention and action. -

Biodiversity in Drylands: Challenges And

1 The Global Drylands Partnership CIDA UNSO UNDP/GEF IIED IUCN WWF NEF BIODIVERSITY IN DRYLANDS: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE USE Written by Edouard G. Bonkoungou (IUCN) Edited by Maryam-Naimir-Fuller (UNDP/GEF) 2 Tables of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 4 2. DEFINITION AND EXTENT OF DRYLANDS ........................................................................................... 4 3. DRYLAND BIODIVERSITY STATUS AND TRENDS .................................................................................. 5 3.1- Driving Forces of Biodiversification in Drylands........................................................................................ 5 3.2- Status of Dryland Biodiversity..................................................................................................................... 6 3.3 - Special Features of Dryland Biodiversity ................................................................................................... 7 3.4 - Threats to Dryland Ecosystems and Species Diversity……………………………………………………12 4. BIODIVERSITY, DESERTIFICATION AND CLIMATE INTERACTIONS IN DRYLANDS.................... 14 5 . CONSERVATION,SUSTAINABLE USE OF DRYLAND BIODIVERSITY - A CALL FOR ACTION.... 15 5.1- Lessons Learnt From -

Issues Brief: Drylands and Climate Change

SEPTEMBER 2019 DRYLANDS AND CLIMATE CHANGE Drylands are home to species and people that have developed unique strategies to cope with the climatic variability unique to this environment. Drylands are particularly affected by climate change through changing rainfall patterns and land degradation, which reduces the ability of species and people to cope with dryland conditions. Climate change will likely aggravate poverty, food and water insecurity in drylands. Alongside ambitious emission cuts, countries can restore dryland ecosystems and sustainably manage land to address climate change in drylands. the21st century, with as much as 80% of this expansion occurring in developing countries. What is the issue? The dramatic shifts in rainfall patterns caused by Drylands are ecosystems, such as rangelands, climate change are expected to affect both the grasslands and woodlands, which occupy over 40% of quantity and distribution of water. Loss of the terrestrial surface, and are characterised by high vegetation could lead to the hardening of the soil temporal and spatial rainfall variability. Drylands are surface, increased water runoff and consequently dominated by grasslands, which cover more than one reduced ground water recharge. The frequency and fifth of the planet’s terrestrial surface. intensity of droughts are also expected to increase with climate change. This is of particular concern in drylands, where species and communities already have to cope with dramatic climatic variations. Climate change is likely to accelerate land degradation, referred to in drylands as desertification. Land degradation is defined as a loss of the ecological and economic productivity of land. About 20-35% of drylands already suffer some form of land degradation, and this is expected to expand significantly under different emission scenarios. -

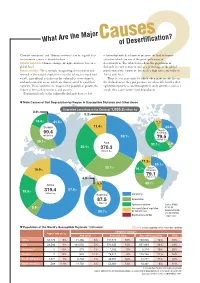

What Are the Major Causes of Desertification?

What Are the Major Causesof Desertification? ‘Climatic variations’ and ‘Human activities’ can be regarded as relationship with development pressure on land by human the two main causes of desertification. activities which are one of the principal causes of Climatic variations: Climate change, drought, moisture loss on a desertification. The table below shows the population in global level drylands by each continent and as a percentage of the global Human activities: These include overgrazing, deforestation and population of the continent. It reveals a high ratio especially in removal of the natural vegetation cover(by taking too much fuel Africa and Asia. wood), agricultural activities in the vulnerable ecosystems of There is a vicious circle by which when many people live in arid and semi-arid areas, which are thus strained beyond their the dryland areas, they put pressure on vulnerable land by their capacity. These activities are triggered by population growth, the agricultural practices and through their daily activities, and as a impact of the market economy, and poverty. result, they cause further land degradation. Population levels of the vulnerable drylands have a close 2 ▼ Main Causes of Soil Degradation by Region in Susceptible Drylands and Other Areas Degraded Land Area in the Dryland: 1,035.2 million ha 0.9% 0.3% 18.4% 41.5% 7.7 % Europe 11.4% 34.8% North 99.4 America million ha 32.1% 79.5 million ha 39.1% Asia 52.1% 5.4 26.1% 370.3 % million ha 11.5% 33.1% 30.1% South 16.9% 14.7% America 79.1 million ha 4.8% 5.5 40.7% Africa -

A World-Ecological Reading of Drought in Thea Astley's

humanities Article Dry Country, Wet City: A World-Ecological Reading of Drought in Thea Astley’s Drylands Ashley Cahillane Discipline of English, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland; [email protected] Received: 6 January 2020; Accepted: 16 July 2020; Published: 11 August 2020 Abstract: Using a postcolonial and world-ecological framework, this article analyses the representation of water as an energy source in Thea Astley’s last and most critically acclaimed novel Drylands (1999). As environmental historians have argued, the colonial, and later capitalist, settlement of Australia, particularly the arid interior, was dependent on securing freshwater sources—a historical process that showed little regard for ecological impact or water justice until recent times. Drylands’ engagement with this history will be considered in relation to Michael Cathcart’s concept of ‘water dreaming’ (2010): the way in which water became reimagined after colonization to signify the prospect of economic growth and the consolidation of settler belonging. Drylands self-consciously incorporates predominant modes of ‘water dreaming’ into its narrative, yet resists reducing water to a passive resource. This happens on the level of both content and form: while its theme of drought-induced migration is critical of the past, present, and future social and ecological effects of the reckless extraction of freshwater, its nonlinear plot and hybrid form as a montage of short stories work to undermine the dominant anthropocentric colonial narratives that underline technocratic water cultivation. Keywords: Australian literature; world-ecology; blue humanities; world literature; ecocriticism; postcolonial ecocriticism 1. Introduction Water dictates Australia’s ecology, economy, and culture. Though surrounded by water, Australia is the world’s driest inhabited continent. -

WOLRD DAY to COMBAT DESERTFICATION 2014 Events Around the World ARGENTINA ARMENIA

WOLRD DAY TO COMBAT DESERTFICATION 2014 Events around the world The slogan for the 2014 World Day to Combat Desertification is “Land belongs to the future - let's climate proof it." See how different stakeholders celebrated the Day and what events and activities took place in different parts of the world. ARGENTINA The Argentinean NGO Fundacion Agreste in collaboration with the University of Moròn and the Instituto de Estudios ambientales sociales y Resolución de conflictos will organize an event to celebrate June 17 and present the conclusions of the Environmental Management Indicators for the Republic of Argentina. The Ministry of Education of Argentina will show on its channel "Canal Encuentro" an environmental video focusing on climate change and desertification. Learn more at http://encuentro.gob.ar/programas/serie/8014/188 ARMENIA A national information agency has organized a press conference with representatives of CSOs and scientists working in the field of DLDD as well as the UNCCD National Focal Point of Armenia. The interview with the National Focal Point was broadcasted in the Armenian Channel “A1+”. An article about the World Day to Combat Desertification was published on the website of the Ministry of Nature Protection of the republic of Armenia. 1 WOLRD DAY TO COMBAT DESERTFICATION 2014 Events around the world BELARUS A 2-day seminar “Improving Legal Regulation to Combat Land Degradation and Desertification” took place in the Biaroza District, Brest region of Belarus. Governmental and local authorities, parliamentarians, representatives of local communities and NGOs, scientist and mass media exposed current challenges and risks Belarus is facing with respect to desertification and stressed the necessity to develop and test sustainable approaches and innovative mechanisms to address land degradation and combat desertification. -

Economics of Dryland Management

The Economics of Dryland Management The Economics of Dryland Management John A. Dixon East-West Center David E.James Macquarie University PaulB. Sherman East-West Center EARTHSCAN PUBLICATIONS LTD LONDON First published in 1989 by Earthscan Publications Ltd 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H ODD Copyright © 1989 by United Nations Environment Programme - The Australian Government - East-West Center All rights reserved 1 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Dixon, John A. (|ohn Alexander), 1946- The economics of dryland management. 1. Arid regions. Natural resources. Management I. Title •. James, David E. III. Sherman, Paul B. 333.73 ISBN 1-85383-052-6 Production by David Williams Associates 01-521 4130 Typeset by TJB Photosetting Ltd, Grantham, Lincolnshire 1 Printed by WBC Ltd, Bristol Earthscan Publications Limited is an editorially independent and wholly owned subsidiary of the International Institute for Environment and Development. Contents Foreword xi Preface xv 1. The Dryland Problem 1 Dimensions of the problem, 5 History and background of dryland usage; Current conditions in the drylands; The future of the drylands References 12 2. Dryland Characteristics and the Degradation Process 15 . Physical and biological characteristics 15 Climate; Surface water and groundwater resources; Topography and soils; Vegetation; Animal populations Degrada tion and land use 24 Degradation processes; Livestock production; Rainfed crop production; Irrigated agriculture; Forestry and agroforestry; Other land uses Social and institutional factors -

BUILDING RESILIENCE in DRYLANDS Global Guidelines for Restoration of Forest Landscapes and Degraded Lands

BUILDING RESILIENCE IN DRYLANDS Global guidelines for restoration of forest landscapes and degraded lands Forests play crucial ecological, social and economic roles in drylands, but in many regions they have become degraded. Worldwide, millions of hectares of dryland forest landscapes need to be restored to help tackle global challenges such as poverty, climate change, soil erosion and desertification. In collaboration with its partners, FAO has therefore developed global guidelines for restoration of forest landscapes and degraded lands to build resilience in drylands. This brochure describes the main elements of the guidelines. ©FAO/Issouf Sanogo ©FAO/Issouf Vulnerable women and households, Niger WHY DRYLAND FORESTS Drylands are defined1 as those regions where: • evapotranspiration exceeds precipitation (no matter the amount of precipitation); • water scarcity limits the production of crops, forage, wood and ecosystem services. Forests and trees in drylands play significant roles in conserving biodiversity. They harbour many unique species that are adapted to extreme ecological conditions, and they provide ecosystem goods and services that are essential for people’s livelihoods and well-being (see Box 1). If well managed and properly valued, forests and trees in drylands can help alleviate poverty, provide options for adapting to climate change, limit erosion and prevent and combat desertification. By supporting the millions of people who live in the world’s dry areas, forests and trees in drylands can contribute to FAO’s mandate. ©FAO/Giulio Napolitano ©FAO/Giulio 1 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Drylands Systems. Chapter 22 in: Ecosystems and Human A cattle herder shaking loose pods from a tree to feed the herd, Niger Well-being: Current State and Trends, Volume 1. -

Sudan Country Study

Pastoralism and Conservation in the Sudan Executive Summary Introduction On a global scale, Sudan perhaps ranks first in terms of pastoralists population size. About 66 per cent of Sudan is arid land, which is mainly pastoralists’ habitat. Pastoralism in the Sudan involves about 20 per cent of the population and accounts for almost 40 per cent of livestock wealth [Markakis, 1998: 41]. The livestock sector plays an important role in the economy of the Sudan, accounting for about 20 percent of the GDP, meeting the domestic demand for meat and about 70 percent of national milk requirements and contributing about 20 percent of the Sudan’s foreign exchange earnings. It is also a very significant source of employment for about 80 percent of the rural workforce. In the Sudan it is estimated that the total number of cattle multiplied 21 times between 1917 and 1977, camels 16 times, sheep 12 times and goats 8 times [Fouad Ibrahim, 1984, p.125 in Markakis, 1998: 42]. Their numbers are estimated to have doubled between 1965 and 1986. The rapid rate of animal population increase has been attributed to the introduction of veterinary services and the stimulation of the market. Two periods of exceptional rainfall (1919-1934 and 1950-1965) added momentum to this trend. In the early 1980s there were nearly three million heads of camels, over 20 million cattle, nearly 19 million sheep, and 14 million goats. Livestock estimates for the year 2005 are 38 million heads of cattle, 47 million sheep, 40 million goats and three million camels [Ministry of Animal Resources, 2006]. -

1 ~ Drylands, People and Land Use

CHAPTER 1 Drylands, people and land use CHARACTERISTICS OF DRYLANDS There is no single agreed definition of the term drylands. Two of the most widely accepted definitions are those of FAO and the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD, 2000). FAO has defined drylands as those areas with a length of growing period (LGP) of 1–179 days (FAO, 2000a); this includes regions classified climatically as arid (Plate 1), semi-arid and dry subhumid. The UNCCD classification employs a ratio of annual precipitation to potential evapotranspiration (P/PET). This value indicates the maximum quantity of water capable of being lost, as water vapour, in a given climate, by a continuous stretch of vegetation covering the whole ground and well supplied with water. Thus, it includes evaporation from the soil and transpiration from the vegetation from a specific region in a given time interval (WMO, 1990). Under the UNCCD classification, drylands are characterized by a P/PET of between 0.05 and 0.65. 6 CHAPTER 1 ~ Drylands, people and land use PLATE 1 global biophysical processes by reflecting and A view of dryland (with village absorbing solar radiation and maintaining the in the background) in the Sahel, balance of atmospheric constituents (Ffolliott southern Niger (P. Cenini) et al., 2002). They provide much of the world’s grain and livestock, forming the habitat that supports many vegetable species, fruit trees and micro-organisms. High variability in both rainfall amounts and intensities are characteristics of dryland regions, as are the occurrence of prolonged periods of drought. A drought is defined as a departure from the average or normal conditions, sufficiently prolonged (1-2 years - FAO, 2004) as to affect the hydrological balance and adversely affect ecosystem functioning and the resident populations. -

Global Drylands: a UN System-Wide Response

Global Drylands: A UN system-wide response UNITED NATIONS 1 First published in October 2011 by the United Nations Environment Management Group. © 2011 United Nations This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The United Nations would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in written form from the copyright holders. Permission requests should be sent to permissions@ un.org or [email protected]. The use of information from this publication concerning proprietary products for advertising is not permitted. Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expres- sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of a commercial company or product does not imply endorsement by the cooperating partners. The views ex- pressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Printed on recycled paper. 2 Global Drylands: A UN system-wide response Prepared by the Environment Management -

Agrobiodiversity in Drylands When It Rains and Drylands Bloom, One Realises the Remarkable Diversity of Living Organisms They Harbour

Photo: Michael Martin Agrobiodiversity in drylands When it rains and drylands bloom, one realises the remarkable diversity of living organisms they harbour. Long overlooked, this diversity is crucial to the food security of a large share of the world’s population. Drylands cover about 41 % of the earth’s land surface. More Drylands encompass savannah woodlands, grassland, deserts than two-thirds of their area lie in developing countries, and other areas with inconsistent rainfall, often high tem- where around 90% of the two billion dryland inhabitants peratures, and great seasonal and spatial variations of the live – about a quarter of the world’s population. fauna and flora. Some drylands are too dry even for the most extensive pasturage. The bulk is rangeland and is used main- ly for grazing. The remainder is cultivated with rain fed crops, and a small but growing percentage is under irrigation. Many dryland inhabitants are poor and depend on local plants and animals for their survival, food and income. Their century-old food production and livelihood strategies opti- mise the sustainable use of available resources. The world’s Photo: Michael Martin 120 million pastoralists have especially well adapted to dry- land conditions. The breeds they have developed and their Drylands and dryland biodiversity mobile herding strategies enable them to produce food in areas too dry for cropping. Drylands cover about 61 billion ha. About 16 % of this area is hyper-arid, 26 % arid, 37 % semi-arid and 21 % dry-subhumid. To date there are approximately 1.4 million or more named species in the world – plants, Mobile herding of Borana pastoralists animals, fungi and microbes.