Boardman V. Inslee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omnibus June 2019 Dem Primary

Democratic Dividing Lines Verified Voter Omnibus Survey N=484 Democrats or Democratic leaners June 22 - June 25, 2019 !X!1 Key Findings • Biden’s lead among 24 announced Democratic candidates has narrowed by 6-points since May to 32% of the Democratic vote. • Biden’s 6-point drop came with a concurrent 6-point gain by Elizabeth Warren to 11% of the Democratic vote, or 4- points behind Bernie Sanders who takes 15% of the Democratic vote. • Biden continues to lead both Sanders and Warren in head to head match-ups, but his lead has narrowed to 30-points from both Sanders and Warren, down from 36-points ahead of Sanders and 47-points ahead of Warren in May. • 73% of Democrats plan to watch the debates, or coverage of the debates. Ahead of the kickoff of tonight’s debates, we tested Democratic concern about two recent pieces of news about Biden — his flip flopping on the Hyde Amendment’s impact on access to abortion, and past associations with segregationists. • We found the Hyde Amendment resonates more strongly with Democratic voters, with 39% of Democrats concerned about Biden’s stance on the Hyde Amendment, and 22% concerned about his associations with segregationists. • Particularly concerned are women, African Americans, younger voters, and more educated voters. !2 Methodology • Using a voter file-matched online panel, we surveyed n=1,006 registered voters across the country from June 22 to June 25, 2019, with a sample of 484 Democrats or Democratic-leaning Independents. • With our third monthly tracking survey of 2019, we were able to confirm the voting history of participants and track changes in the attitudes and behaviors of key 2020 voters since our last survey of verified Democratic or Democratic-leaning Independent voters from May 20 to May 21, 2019. -

Biden Is Only Leading Dem to Top Trump in Ohio, Quinnipiac University Poll Finds; Former V.P

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director (203) 535-6203 Rubenstein Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: JULY 25, 2019 BIDEN IS ONLY LEADING DEM TO TOP TRUMP IN OHIO, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; FORMER V.P. HAS BIG LEAD IN DEMOCRATIC PRIMARY Former Vice President Joseph Biden leads President Donald Trump 50 – 42 percent in the critical swing state of Ohio, the only leading Democratic candidate to top the Republican incumbent, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. The other leading Democratic contenders each are locked in a dead heat with President Trump, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds: 46 percent for Trump to Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders with 45 percent; Trump at 46 percent to Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren at 45 percent; 44 – 44 percent between Trump and California Sen. Kamala Harris; 44 – 44 percent between Trump and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg; 44 percent for Trump to 43 percent for New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker. Women, black voters and independent voters give Biden his lead in the matchup with Trump. Biden leads 53 – 40 percent among women, as men are split with 46 percent for Biden and 45 percent for Trump. White voters are divided, with 48 percent for Trump and 45 percent for Biden. Black voters go Democratic 84 – 8 percent. Independent voters go to Biden 55 – 32 percent. Republicans back Trump 86 – 10 percent as Biden leads 96 – 2 percent among Democrats. “Former Vice President Joseph Biden calls himself a blue-collar guy. With Ohio certainly a blue-collar state, it is no surprise he is the Democrat who runs best against President Donald Trump and is solidly ahead in the Democratic primary in the Buckeye State,” said Peter Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Poll. -

April 23, 2019 April Omni B Survey, Data for Progress Items

To: Data for Progress From: YouGov Blue Date: April 23, 2019 April Omni B survey, Data for Progress Items [primaryvote] Next year, there will be a presidential $state_election_text in [state] to select nominees for president for the Democratic and Republican parties. Will you... <1> Definitely [vote or participate] <2> Probably [vote or participate] <3> Maybe [vote or participate] <4> Probably not [vote or participate] <5> Definitely not [vote or participate] [partyvote] And if you were to [vote or participate], would you [vote or participate] in the... <1> Democratic [primary or caucus] <2> Republican [primary or caucus] <3 fixed> Not sure [CHOICE20] Thinking about the 2020 Democratic presidential [primary or caucus] in your state, which candidate or candidates are you considering voting for? Select all that apply. <1> Joe Biden <2> Bernie Sanders <3> Kamala Harris <4> Beto O’Rourke <5> Cory Booker <6> Amy Klobuchar <7> Elizabeth Warren <8> John Hickenlooper <9> Kirsten Gillibrand <10> John Delaney <11> Julián Castro <12> Stacey Abrams <13> Tammy Baldwin <14> Bill DeBlasio <15> Tulsi Gabbard <16> Pete Buttigieg <17> Jay Inslee <18> Tim Ryan <19> Seth Moulton <20> Eric Swalwell <21> Andrew Yang <22> Marianne Williamson <23> Mike Gravel <24> Steve Bullock <25> Michael Bennet <26> Wayne Messam <27 fixed> None of these [RANK20] And of those candidates, please ranK them from the candidate you most prefer to the candidate you would least prefer. <1 (if selected in CHOICE20)> Joe Biden <2 (if selected in CHOICE20)> > Bernie Sanders <3 (if selected -

Executive Summary

SAINT ANSELM COLLEGE SURVEY CENTER JULY 2019 POLL DEMOCRATIC PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY These results are from the Saint Anselm College Survey Center poll based on interviews with 351 New Hampshire registered voters expressing an intention to vote in the upcoming Democratic Presidential Primary. Interviews were conducted by landline and cellular phone between July 10 th and July 12 th , 2019. The survey has a margin of sampling error of 5.2% with a confidence interval of 95%. Data are weighted for age, gender and geography based on a voter demographic model derived from historical voting patterns, but are not weighted by party registration or party identification. Respondents were asked for their impression of 9 candidates for the Democratic nomination for President. The names were presented in random order. Respondents were then asked to name a candidate for whom they would vote. “I’m now going to read a list of people that are running for the Democratic Presidential nomination. After each name, I would like you to tell me if you have a favorable impression, unfavorable impression, or no opinion of that person. If you have never heard of them, please let me know.” “If the presidential primary election were held today, which candidate would you vote for?” New Hampshire Institute of Politics Executive Director Neil Levesque summarized the results, saying, “In the Saint Anselm College Survey Center’s first look at the New Hampshire Democratic Primary field since the first series of debates, Joe Biden continues to hold a lead in the ballot test, with 21% of primary voters expressing a preference for the former Vice President. -

What's the Matter with Bill De Blasio?

What’s the Matter With Bill de Blasio? | 1 Willful bungling of the coronavirus crisis cuts across ideologies and political parties. That’s the lesson that we learn from the story of Bill de Blasio. He is very different, across many different dimensions, than Donald Trump. But it turns out that he shares something important with Trump: a tendency to place personality over expertise. De Blasio’s initial reaction to the coronavirus was a lot more Donald Trump than Jay Inslee. Washington State Governor Inslee faced an outbreak at around the same time and responded decisively. De Blasio, like Trump, seemed more concerned about the economic impact of control measures than with the virus itself. At the beginning of March, De Blasio said the virus couldn’t be spread through casual contact in public places. A week later, as the disease was spreading rapidly in the city, he was still telling people to take basic precautions but otherwise go about their business. As evidence of the threat to the city grew, de Blasio continued to spread false optimism. He told New Yorkers to “go about their lives” if they weren’t sick. On March 10, he did reluctantly close gyms, but he made one final visit to his own gym before the closure. The message to New Yorkers until the middle of March was to take moderate precautions but not to change their everyday lives. By then, the disease was everywhere in the city. While Jay Inslee in Washington began to encourage social distancing early on, de Blasio actively discouraged it. -

Suffolk University/Boston Globe

SUPRC/Boston Globe August 2019 FINAL NH DEM PRIMARY AUGUST Region: (N=500) n % West/North ------------------------------------------------------- 131 26.20 Central ------------------------------------------------------------ 127 25.40 Hillsborough ------------------------------------------------------ 137 27.40 Rockingham ------------------------------------------------------ 105 21.00 INTRO SECTION> Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk (SUFF-ick) University and I would like to get your opinions on some questions about the upcoming Democratic Primary in New Hampshire. Would you be willing to spend five minutes answering some brief questions? (quota) A. Are you a resident of New Hampshire? (N=500) n % Yes ----------------------------------------------------------------- 500 100.00 1. Gender (N=500) n % Male ---------------------------------------------------------------- 224 44.80 Female ------------------------------------------------------------ 276 55.20 2. Thinking about the Democratic Primary for President coming up in six months, how likely are you to vote in the Democratic Primary – would you say you are very likely, somewhat likely, not very likely, or not at all likely to vote in the Democratic Primary? (N=500) n % Very likely--------------------------------------------------------- 448 89.60 Somewhat likely -------------------------------------------------- 52 10.40 3. Are you currently enrolled as a Democrat, Republican, or Undeclared/Independent? (N=500) n % Democrat --------------------------------------------------------- -

National Governors Association 2015-2016 Committees ______

Gary Herbert Terry McAuliffe Dan Crippen Governor of Utah Governor of Virginia Executive Director Chair Vice Chair NATIONAL GOVERNORS ASSOCIATION 2015-2016 COMMITTEES _____________________________________________________________________________________ NGA EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE _____________________________________________________________________________________ Governor Gary Herbert, Utah – Chair Governor Terry McAuliffe, Virginia – Vice Chair Governor John Hickenlooper,Colorado Governor Brian Sandoval, Nevada Governor Dan Malloy, Connecticut Governor Pat McCrory, North Carolina Governor Terry Branstad, Iowa Governor Peter Shumlin, Vermont Governor Mark Dayton, Minnesota Finance Committee Governor Terry McAuliffe, Virginia – Chair Governor Rick Snyder, Michigan Governor Gary Herbert, Utah Governor Peter Shumlin, Vermont Legal Affairs Committee Governor Dennis Daugaard, South Dakota – Chair Governor Dan Malloy, Connecticut Governor Kenneth Mapp, Virgin Island _____________________________________________________________________________________ ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND COMMERCE COMMITTEE _____________________________________________________________________________________ Governor Larry Hogan, Maryland - Chair Governor Earl Ray Tomblin, West Virginia – Vice Chair Governor John Hickenlooper, Colorado Governor Bruce Rauner, Illinois Governor Mike Pence, Indiana Governor Terry Branstad, Iowa Governor Phil Bryant, Mississippi Governor Andrew Cuomo, New York Governor Pat McCrory, North Carolina Governor Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island Governor Kenneth -

Saint Anselm College Survey Center April 2019 Poll Announced/Potential Democratic Presidential Candidate Name Recognition and Ballot Test Results

SAINT ANSELM COLLEGE SURVEY CENTER APRIL 2019 POLL ANNOUNCED/POTENTIAL DEMOCRATIC PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE NAME RECOGNITION AND BALLOT TEST RESULTS These results are from the Saint Anselm College Survey Center poll based on interviews with 698 randomly- selected registered voters in the state of New Hampshire. Interviews were conducted by landline and cellular phone between April 3 rd and April 8 th , 2019. The overall survey has a margin of sampling error of 3.7% with a confidence interval of 95%; the margin of sampling error for questions specific to the 1 st and 2 nd Congressional Districts is 5.3% and 5.1% respectively; the margin of sampling error for questions specific to the Democratic and Republican Presidential Primaries are 5.4% and 6.0% respectively. Data are weighted based on a voter demographic model derived from historical voting patterns, but are not weighted by party registration or party identification. 326 respondents that indicated their intention to vote in the Democratic Presidential Primary were asked for their impression of 14 announced and potential candidates for the Democratic nomination for President. The names were presented in random order. Respondents were then asked to select a candidate for whom they would vote. “Now I’m now going to read a list of people that have announced that they are running for the Democratic Presidential nomination, or have indicated that they are strongly considering it. After each name, I would like you to tell me if you have a favorable impression, unfavorable impression, or no opinion of that person. If you have never heard of them, please let me know.” “If the presidential primary election were held today, which candidate would you vote for?” New Hampshire Institute of Politics Executive Director Neil Levesque summarized the results, saying, “Joe Biden continues to show strength in New Hampshire, as 23% of Democratic Primary voters surveyed indicated that if the NH Primary were held today, they would vote for Biden, followed by 16% for Bernie Sanders, 11% for Pete Buttigieg and 9% for Elizabeth Warren. -

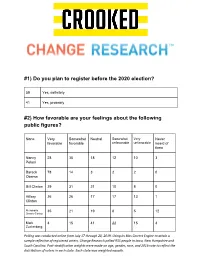

1) Do You Plan to Register Before the 2020 Election? #2) How Favorable Are Your Feelings About the Following Public Figures?

#1) Do you plan to register before the 2020 election? 59 Yes, definitely 41 Yes, probably #2) How favorable are your feelings about the following public figures? None Very Somewhat Neutral Somewhat Very Never favorable favorable unfavorable unfavorable heard of them Nancy 28 30 18 12 10 3 Pelosi Barack 78 14 3 2 2 0 Obama Bill Clinton 29 31 21 10 8 0 Hillary 26 26 17 17 13 1 Clinton Alexandria 35 21 19 8 5 12 Ocasio-Cortez Mark 4 15 41 22 15 3 Zuckerberg Polling was conducted online from July 17 through 20, 2019. Using its Bias Correct Engine to attain a sample reflective of registered voters, Change Research polled 935 people in Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina. Post-stratification weights were made on age, gender, race, and 2016 vote to reflect the distribution of voters in each state. Each state was weighted equally. Joe Biden 36 33 13 9 9 0 Beto 14 32 26 8 5 15 O'Rourke Pete 31 26 17 3 5 18 Buttigieg Bernie 37 29 16 10 8 0 Sanders Kamala 23 34 24 5 3 11 Harris Elizabeth 37 28 18 8 5 5 Warren Cory 16 30 29 6 4 16 Booker Amy 6 20 33 9 2 30 Klobuchar Julián 6 20 32 6 3 33 Castro John 2 8 42 5 3 41 Delaney Tulsi 4 12 30 9 4 41 Gabbard Kirsten 7 21 38 7 4 23 Gillibrand John 2 9 38 5 3 43 Hickenlooper Jay Inslee 2 9 33 3 2 51 Eric 3 12 33 2 1 48 Swalwell © 2019 Change Research [email protected] | changeresearch.com Andrew 5 14 34 6 1 39 Yang Michael 2 7 35 3 2 51 Bennet Marianne 2 3 31 6 4 54 Williamson Tim Ryan 1 9 35 5 4 46 Bill de 2 12 39 13 7 26 Blasio #3) In the November 2016 election, did you vote for: 83 Hillary Clinton, the Democrat 7 Did not vote 5 Donald Trump, the Republican 3 Gary Johnson, the Libertarian 1 Jill Stein, the Green Party #4) In 2020, do you think you will most likely: 100 Vote in the Democratic primary #5) As you may know, Democratic primary debates will occur on June 26 and 27. -

Green New Deal Scorecard Retrospective

GREEN NEW DEAL SCORECARD RETROSPECTIVE November 2019 OVERVIEW Since we launched our Green New Deal scorecard, Democratic candidates — moderates and progressives alike — have released plans that leverage more ambitious emissions targets, a broader array of federal policy tools, and more robust jobs and justice programs. From our first scorecard in June to now, we have seen: +97% +59% increase in median score, from 15.5 increase in average federal direct to 30.5 of 48 investment +8 11 candidates aligned with Data For current Democratic candidates reach Progress emissions targets Thorough or Very Thorough scores, up from 4 in the first scorecard How we scored the plans: Data For Progress devised a Green New Deal scorecard identifying 48 components of a Green New Deal. Candidates got half credit for Green New Deal concepts that they acknowledged, but did not lay out a clear policies or actions to address, and full credit for those that they had policy prescriptions for in their plan; however, these scores did not consider the merits of any particular policy mechanism. For instance, if one candidate asserted his or her intent to invest DOE funds into advanced nuclear research, while another outlined a plan to phase out existing nuclear entirely, both would receive full credit. Moreover, we could only assess qualitatively how the elements of plans worked together cohesively. These scores were tallied to give us a sense of the overall thoroughness of the plan: Very Incomplete = 0 - 12 Thorough = 24.5 - 36 Incomplete = 12.5 - 24 Very Thorough = 36.5 - 48 Green New Deal Scorecard Retrospective /// 1 BUILDING A GREEN NEW DEAL SCORECARD A Green New Deal posits that the next few years of decision-making in Washington will have dramatic consequences for the future of our nation, species and planet. -

Monmouth University Poll IOWA: HEALTH CARE, ENVIRONMENT TOP DEM ISSUES

Please attribute this information to: Monmouth University Poll West Long Branch, NJ 07764 www.monmouth.edu/polling Follow on Twitter: @MonmouthPoll _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Released: Contact: Thursday, April 11, 2019 PATRICK MURRAY 732-979-6769 (cell); 732-263-5858 (office) [email protected] Follow on Twitter: @PollsterPatrick IOWA: HEALTH CARE, ENVIRONMENT TOP DEM ISSUES Biden leads pack; beating Trump a priority for caucusgoers West Long Branch, NJ – Democratic voters in the Hawkeye State like Joe Biden – a lot. The former vice president leads the pack and holds the best favorability rating in a field of two dozen presidential contenders, according to the first Monmouth University Poll of Iowa Democratic voters in the 2020 cycle. Other candidates also have strong favorability ratios that could help them crack the top tier once they become better known to caucusgoers. Health care and environmental concerns are the top issues for Iowa Democrats in deciding who to support for their party’s presidential nomination, but beating President Donald Trump is also a very important consideration. In a field of 24 announced and potential candidates, Biden holds the lead with 27% support among Democratic voters who are likely to attend the Iowa caucuses in February. He is followed by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders (16%), South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg (9%), Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren (7%), California Sen. Kamala Harris (7%), former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke (6%), Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar (4%), New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker (3%), and former cabinet secretary Julián Castro (2%). Former Maryland Rep. John Delaney, New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, Ohio Rep. Tim Ryan, California Rep. -

This Washington Post-ABC News Poll Was Conducted by Telephone June

This Washington Post-ABC News poll was conducted by telephone June 28-July 1 2019, among a random national sample of 1,008 adults, with 65 percent reached on cell phones and 35 percent on landlines. Results have an error margin of plus or minus 3.5 percentage points for the full sample, including design effects due to weighting. Sampling, field work and data processing by Abt Associates of Rockville, MD. (Full methodological details appended at the end.) *= less than 0.5 percent Questions 1-3 held for release. 4. (ASK IF LEANED DEMOCRAT) I'd like you to rate the chances that you will vote in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary or caucus in your state - are you absolutely certain to vote, will you probably vote, are the chances 50-50, or less than that? Don't think Certain Probably Chances Less than will vote No to vote vote 50/50 that (vol.) op. 7/1/19 72 12 9 4 3 * 5. (ASK IF LEANED DEMOCRAT) If the 2020 Democratic primary or caucus in your state were being held today, for whom would you vote? 1/24/19 ---- 4/25/19 ---- ------------ 7/1/19 ------------ Without Without With Without With Reg voters leaners leaners leaners leaners leaners with leaners Joe Biden 9 13 17 21 25 28 Bernie Sanders 4 9 11 13 18 16 Kamala Harris 8 4 4 7 9 11 Elizabeth Warren 2 4 4 7 9 10 Pete Buttigieg 0 5 5 3 3 3 Tulsi Gabbard 0 0 0 1 1 2 Amy Klobuchar 1 1 1 1 1 1 Beto O'Rourke 3 3 4 1 1 1 Andrew Yang 0 * * 1 1 1 Marianne Williamson 0 0 0 1 1 0 Julian Castro * * * * 1 1 Cory Booker 1 1 1 * * * John Hickenlooper * * * * * * Jay Inslee 0 0 0 * * * Michael Bennet 0 * * * * 0 Steve Bullock 1 0 0 0 * * Seth Moulton 0 0 0 0 0 0 Tim Ryan 0 0 0 0 0 0 Bill de Blasio 0 0 0 0 0 0 John Delaney 0 0 0 0 0 0 Kirsten Gillibrand * 0 0 0 0 0 Eric Swalwell 0 0 0 0 0 0 Other 15 5 9 3 4 3 Someone new 1 1 1 * 0 0 No one/None of them 7 3 4 4 4 4 Anyone/Any of them 5 3 2 2 1 2 No opinion 43 46 35 35 19 17 6.