Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2011 Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance Julia A. Fenton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Motor Control Commons Recommended Citation Fenton, Julia A., "Principles of Movement Control That Affect Choreographers' Instruction of Dance" (2011). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1436 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Principles of Movement Control that Affect Choreographers’ Instruction of Dance Julia Fenton Preface The purpose of this paper is to inform choreographers of different motor control and skill learning principles that affect instruction of dance and choreography as well as provide a resource for choreographers to make rehearsals more productive. In order to accomplish this task, I adapted the information presented in three main texts, written by Schmidt and Wrisberg, Schmidt and Lee, and Fairbrother, in order for it to be useful to choreographers. I have included dance examples rather than sport examples in order for the choreographer to more easily relate to the information. The in-text citations in this paper were kept to a minimum in order for it to be read more easily. -

CHOREOGRAPHY BASICS By: Max Perry to Choreograph an Effective Routine, a Dancer Will Use Several Techniques to Create a Dance T

CHOREOGRAPHY BASICS By: Max Perry To choreograph an effective routine, a dancer will use several techniques to create a dance that will not only fit the music, but will feel good when danced. The tools we use as choreographers are knowledge of the dance components, a basic idea of phrasing music, and an idea of how the material is to be used (the dancers or organization or company, etc.). ______________________________________ POINTS TO REMEMBER: 1. “A body in motion tends to stay in motion”. There is an initial force required to put the body in motion. Every time there is a change in the directional movement, there is additional force required to make the change. Too many abrupt changes in direction are not as comfortable as letting the body flow in the direction it wants to go, then gradually slow before changing directions. This does not mean you should slow down before every turn - I am referring to energy output only! 2. Choose music that has a wide audience appeal. You do not want a piece of music that sounds dated. The song should sound good every time it is played. If you want artists to take notice, or a national release, the rule is if you hear the song on the radio, it is too late. These songs were recorded months ago. Major established artists do not need a dance. Never go for the obvious - choose a cut from the album that may be released as a single or use a newer artist - possibly an independent artist. 3. Choose material that has a wide audience appeal. -

The THREE's a CROWD

The THREE’S A CROWD exhibition covers areas ranging from Hong Kong to Slavic vixa parties. It looks at modern-day streets and dance floors, examining how – through their physical presence in the public space – bodies create temporary communities, how they transform the old reality and create new conditions. And how many people does it take to make a crowd. The autonomous, affect-driven and confusing social body is a dynamic 19th-century construct that stands in opposition to the concepts of capitalist productivity, rationalism, and social order. It is more of a manifestation of social dis- order: the crowd as a horde, the crowd as a swarm. But it happens that three is already a crowd. The club culture remembers cases of criminalizing the rhythmic movement of at least three people dancing to the music based on repetitive beats. We also remember this pandemic year’s spring and autumn events, when the hearts of the Polish police beat faster at the sight of crowds of three and five people. Bodies always function in relation to other bodies. To have no body is to be nobody. Bodies shape social life in the public space through movement and stillness, gath- ering and distraction. Also by absence. Regardless of whether it is a grassroots form of bodily (dis)organization, self-cho- reographed protests, improvised social dances, artistic, activist or artivist actions, bodies become a field of social and political struggle. Together and apart. ARTISTS: International Festival of Urban ARCHIVES OF PUBLIC Art OUT OF STH VI: SPACE PROTESTS ABSORBENCY -

Choreography for the Camera: an Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1992 Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study Vana Patrice Carter Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Carter, Vana Patrice, "Choreography for the Camera: An Historical, Critical, and Empirical Study" (1992). Master's Theses. 894. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/894 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY by Vana Patrice Carter A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1992 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. CHOREOGRAPHY FOR THE CAMERA: AN HISTORICAL, CRITICAL, AND EMPIRICAL STUDY Vana Patrice Carter, M.A. Western Michigan University, 1992 This study investigates whether a dance choreographer’s lack of knowledge of film, television, or video theory and technology, particularly the capabilities of the camera and montage, restricts choreographic communication via these media. First, several film and television choreographers were surveyed. Second, the literature was analyzed to determine the evolution of dance on film and television (from the choreographers’ perspective). -

The Cunningham Costume: the Unitard In-Between Sculpture and Painting Julie Perrin

The Cunningham costume: the unitard in-between sculpture and painting Julie Perrin To cite this version: Julie Perrin. The Cunningham costume: the unitard in-between sculpture and painting. 2019. hal- 02293712 HAL Id: hal-02293712 https://hal-univ-paris8.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02293712 Submitted on 31 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SITE DES ETUDES ET RECHERCHES EN DANSE A PARIS 8 THE CUNNIN Julie PERRIN GHAM COS TUME: THE UNITARD IN-BETWEEN SCULPTURE AND PAINTING Translated by Jacqueline Cousineau from: Julie Perrin, « Le costume Cunningham : l’académique pris entre sculpture et pein- ture », Repères. Cahier de danse, « Cos- tumes de danse », Biennale nationale de danse du Val-de-Marne, n° 27, avril 2011, p. 22-25. SITE DES ETUDES ET RECHERCHES EN DANSE A PARIS 8 THE Julie PERRIN CUNNINGHAM COSTUME : THE UNITARD IN- Translated by Jacqueline Cousineau BETWEEN SCULPTURE from: Julie Perrin, « Le costume Cun- ningham : l’académique pris entre AND PAINTING sculpture et peinture », Repères. Ca- hier de danse, « Costumes de danse », Biennale nationale de danse du Val- de-Marne, n° 27, avril 2011, p. 22-25. -

Department of Dance and Choreography 1

Department of Dance and Choreography 1 DANC 102. Modern Dance Technique I and Workshop. 3 Hours. DEPARTMENT OF DANCE AND Continuous courses; 1 lecture and 6 studio hours. 3-3 credits. These courses may be repeated for a maximum total of 12 credits on the CHOREOGRAPHY recommendation of the chair. Prerequisites: completion of DANC 101 to enroll in DANC 102. Dance major or departmental approval. Fundamental arts.vcu.edu/dance (http://arts.vcu.edu/dance/) study and training in principles of modern dance technique. Emphasis is on body alignment, spatial patterning, flexibility, strength and kinesthetic The VCU Department of Dance and Choreography offers a pre- awareness. Course includes weekly group exploration of techniques professional program that provides students with numerous related to all areas of dance. opportunities for individual artistic growth in a community that values communication, collaboration and self-motivation. The department DANC 103. Survey of Dance History. 3 Hours. provides an invigorating educational environment designed to prepare Continuous courses; 3 lecture hours. 3-3 credits. Prerequisites: students for the demands and challenges of a career as an informed and completion of DANC 103 to enroll in DANC 104. Dance major or engaged artist in the field of dance. departmental approval. First semester: dance from ritual to the contemporary ballet and the foundations of the Western aesthetic as it Graduates of the program thrive as performers, makers, teachers, relates to dance, and the development of the ballet. Second semester: administrators and in many other facets of the field of dance. Alongside Western concert dance from the aesthetic dance of the late 1800s general education courses, dance-focused academics and creative- to contemporary modern dance. -

Ceroc® New Zealand Competition Rules, Categories and Judging Criteria

Version: April 2018 Ceroc® New Zealand Competition Rules, Categories and Judging Criteria Ceroc® competition events are held in different regions across New Zealand. The rules for the Classic and Cabaret categories as set out in this document will apply across all of these events. Event organisers will provide clear details for all Creative category rules, which may differ between events. Not all categories listed below will necessarily be present at every event. Each event may have their own extra regional Creative categories that will be detailed on the event organiser’s web pages, which can be found via www.cerocevents.co.nz. Contact the event organiser for further details of categories not listed in this document. Contents 1 Responsibilities 1.1 Organiser Responsibilities 1.2 Competitor Responsibilities 2 Points System for Competitor Levels 2.1 How it works 2.2 Points Registry 2.3 Points as they relate to Competitor Level 2.4 Earning Points 2.5 Teachers Points 2.6 International Competitors 3 General Rules 3.1 Ceroc® Style 3.2 Non-Contact Dancing 3.3 Floorcraft 3.4 Aerials 3.5 Newcomer Moves 4 Classic Categories 4.1 Freestyle 4.2 Dance With A Stranger (DWAS) 5 Cabaret Categories 5.1 Showcase 5.2 Newcomer Teams 5.3 Intermediate and Advanced Teams 6 Creative Categories 6.1 to 6.15 7 Judging 7.1 Judging Criteria 7.2 Penalties and Disqualifications Version: April 2018 1 Responsibilities 1.1 Organiser Responsibilities The organiser is responsible for ensuring the event is run professionally and fairly. This is a complex undertaking and more information can be provided by the organiser or Ceroc® Dance New Zealand (Ceroc® NZ) upon request. -

Eve of Kupalo

Gordon Gordey, Director and Dancemaker Ukrainian Canadian Dance Works Created for The Shumka Dancers, Canada’s Professional Ukrainian Dance Company Eve of Kupalo - a Midsummer’s Night Mystery Masque Conceived and Directed by Gordon Gordey Choreographed by Dave Ganert Additional Choreography by John Pichlyk and Tasha Orysiuk Original Music Composed and Arranged by Andriy Shoost Sets and Costumes designed by Maria Levitska Additional Costumes designed by Oksana Paruta and Robert Shannon Masks created by Randall Fraser In January 2007, I created a concept and began writing the dance libretto for Eve of Kupalo - a Midsummer’s Night Mystery Masque as a contemporary Ukrainian folk dance dramatic narrative ballet with video projection. Over the decades I had seen numerous Ukrainian dance companies stage performances based upon the rituals of Kupalo and the midsummer solstice. In 30 years with the Shumka Dancers I too performed, from time to time, in dances based upon Kupalo, the first such performance taking place in the early 1970’s. The performances I saw and those I performed in seemed to become locked in a very standard formula. I could predict what the choreography was going to be in Kupalo before I even entered the theatre. The dance would typically start with female dancers weaving across the stage in a version of a chain style folk dance (Vesnianka or Chorovod) and move on to a dance where female dancers would begin to weave wreathes, which usually with the assistance of a stage lighting change depicting the passage of time, resulted in the wreathes magically becoming completed. These wreathes would be symbolically placed into a stream which was nothing more than placing the wreathes upon the stage floor. -

Emotional Storytelling Choreography—A Look Into the Work of Mia Michaels

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Emotional Storytelling Choreography—A Look Into The Work of Mia Michaels Bethany Emery Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2534 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bethany Lynn Emery 2011 All Right Reserved Emotional Storytelling Choreography—A Look Into The Work of Mia Michaels A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Bethany Lynn Emery M.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2011 M.A.R., Liberty Theological Seminary, 2003 BA, Alma College, 2001 Directors: Amy Hutton and Patti D’Beck, Assistant Professors, Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia July 2011 ii Acknowledgement The author would like to thank several people. I would like to thank my committee members Professor Amy Hutton, Dr. Noreen Barnes and Professor Patti D’Beck for sticking with me through this process and taking time during their summer plans to finish it out. I especially would like to thank Professor Hutton for her guiding hand, honest approach while also having an encouraging spirit. I would like to thank friends Sarah and Lowell for always being there for me though the happy and frustrating days. -

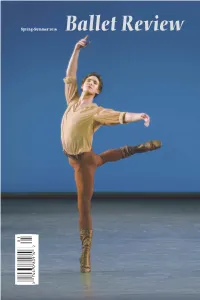

Spring-Summer 2019 Ballet Review

Spring-Summer 2019 Ballet Review 4 Philadelphia – Eva Shan Chou 5 New York – Karen Greenspan 7 Los Angeles – Eva Shan Chou 9 New York – Susanna Sloat 11 Williamstown – Christine Temin 12 New York – Karen Greenspan Susanna Sloat 16 Tokyo – Vincent Le Baron 95 Rennie Harris and Ronald K. Brown 18 Jacob’s Pillow – Christine Temin Celebrate Alvin Ailey 20 Toronto – Gary Smith Robert Greskovic 22 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 100 Chopiniana 25 London – Joseph Houseal 25 Vienna – Vincent Le Baron 109 Judson Dance Theater 27 New York – Susanna Sloat Michael Langlois 28 Miami – Michael Langlois 114 Awakenings 29 Toronto – Gary Smith 31 Venice – Joel Lobenthal Karen Greenspan 32 London – Gerald Dowler 119 In the Court of Yogyakarta 35 Havana – Gary Smith Marian Smith 37 Washington, D.C. – Lisa Traiger 125 The Metropolitan Balanchine 39 London – John Morrone 40 Chicago – Joseph Houseal Gerald Dowler 42 Milan – Vincent Le Baron 141 An Autumn in Europe Alexei Ratmansky Sophie Mintz 44 Staging Petipa’s Harlequinade 146 White Light at ABT Lynn Garafola George Washington Cable 151 Raymonda, 1946 56 The Dance in Place Congo Karen Greenspan Michael Langlois 161 Drive East 2018 63 A Conversation with Karen Greenspan Clement Crisp 168 A Conversation with Maya Joseph Houseal Kulkarni and Mesma Belsaré 76 A Quiet Evening, in Two Acts Francis Mason Ian Spencer Bell 171 Ben Belitt on Graham 82 Women Onstage Gary Smith Michael Langlois 175 A Conversation with Grettel Morejón 86 A Conversation with Hubert Goldschmidt Stella Abrera 177 Rodin and the Dance 207 London Reporter – Louise Levene 218 Dance in America – Jay Rogoff 220 Music on Disc – George Dorris Cover photo by Paul Kolnik, NYCB: Joseph Gordon in Dances at a Gathering. -

Guide to Dance 2018-2019 Study Guide

GUIDE TO DANCE 2018-2019 STUDY GUIDE Learn about the art of dance and go behind-the-scenes with a professional dance company. Written and compiled by Ambre Emory-Maier, Director of Education, and other contributors l ©2018 BalletMet Columbus TABLE OF CONTENTS Behind the Scenes ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Brief History of BalletMet ................................................................................................................................. 3 BalletMet Offerings ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The Five W’s and H of Dance .......................................................................................................................... 5 Brief History of Ballet ..................................................................................................................................... 6-7 Important Tutu Facts ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Important Pointe Shoe Facts .......................................................................................................................... 9 Glossary of Dance Terms ......................................................................................................................... 10-12 Ballet Terminology.......................................................................................................................................... -

Preparatory Dance Program Guidelines

Table of Contents DANCE AT PEABODY 3 ARTISTIC STAFF 4 DANCE FACULTY 5 TRAINING PROGRAMS 8 Young Children’s Program 8 Primary Ballet Program 8 Pre-Professional Program 9 Open Program 11 Estelle Dennis/Peabody Dance Training Program For Boys 12 PREPARATORY DANCE POLICIES 13 APPERANCE GUIDELINES 14 ATTENDANCE POLICIES AND PROCEDURES 15 PERFORMANCE INFORMATION 16 OTHER DANCE OPPORTUNITIES 17 2 Peabody Preparatory Dance The Dance Department of the Peabody Preparatory is one of the oldest continuously-operating dance training cen- ters in the United States. Starting with the first class in eu- rhythmics offered in 1914, and throughout its remarkable life span, the Preparatory Dance Department has pio- neered new dance forms, mounted numerous collabora- tive projects, partnered with prominent figures in 20th and 21st century American dance, and produced accomplished professional dancers, choreographers, directors, and teachers. Barbara Weisberger, visionary leader and founder of Penn- sylvania Ballet, served as Artistic Adviser for the Preparatory Dance Department from 2001-2018. Working closely with late Director Carol Bartlett (Chair 1988-2012), Weisberger reinvigorated the ballet curriculum and expanded prepara- tory dance’s programing. Now Under the leadership of Melissa Stafford, Chair since 2012, Preparatory Dance is keeping in step with the progression of American dance into the 21st century and remains committed to: offering high-quality dance training for stu- dents of all levels age 3 to adult; presenting imaginative professional-level perfor- mances; offering Pre-Professional Ballet and Contemporary dance summer inten- sives; partnering with our community through master classes, seminars, work- shops, and other dance events – most offered free of charge; and training and supporting male dancers through the ground-breaking Estelle Dennis/Peabody Dance Training Program for Boys.