Groundhog Day: Finding an Invincible Summer in the Deepest Punxsutawney Winter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton at the Paramount Seattle

SPECIAL EDITION • FEBRUARY 2018 ENCORE ARTS PROGRAMS • SPECIAL EDITION HAMILTON FEBRUARY 2018 FEBRUARY PROGRAMS • SPECIAL EDITION HAMILTON ARTS ENCORE HAMILTON February 6 – March 18, 2018 Cyan Magenta Yellow Black Inks Used: 1/10/18 12:56 PM 1/11/18 11:27 AM Changes Prev AS-IS Changes See OK OK with Needs INITIALS None Carole Guizetti — Joi Catlett Joi None Kristine/Ethan June Ashley Nelu Wijesinghe Nelu Vivian Che Barbara Longo Barbara Proofreader: Regulatory: CBM Lead: Prepress: Print Buyer: Copywriter: CBM: · · · · Visual Pres: Producer: Creative Mgr Promo: Designer: Creative Mgr Lobby: None None 100% A N N U A L UPC: Dieline: RD Print Scale: 1-9-2018 12:44 PM 12:44 1-9-2018 D e si gn Galle r PD y F Date: None © 2018 Starbucks Co ee Company. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. ee Company. SBX18-332343 © 2018 Starbucks Co x 11.125" 8.625" Tickets at stgpresents.org SKU #: Bleed: SBUX FTP Email 12/15/2017 STARBUCKS 23 None 100% OF TICKET SALES GOOF TOTHE THE PARTICIPATING MUSIC PROGRAMS HIGH SCHOOL BANDS — FRIDAY, MARCH 30 AT 7PM SBX18-332343 HJCJ Encore Ad Encore HJCJ blongo014900 SBX18-332343 HotJavaCoolJazz EncoreAd.indd HotJavaCoolJazz SBX18-332343 None RELEASED 1-9-2018 Hot Java Cool Jazz None None None x 10.875" 8.375" D i sk SCI File Cabinet O t h e r LIVE AT THE PARAMOUNT IMPORTANT NOTES: IMPORTANT Vendor: Part #: Trim: Job Number: Layout: Job Name: Promo: File Name: Proj Spec: Printed by: Project: RELEASE BEFORE: BALLARD | GARFIELD | MOUNTLAKE TERRACE | MOUNT SI | ROOSEVELT COMPANY Seattle, 98134 WA 2401 Utah Avenue South2401 -

Casting Complete for Goodspeed's Moving New Musical Hi, My Name Is

NEWS RELEASE FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: Elisa Hale at (860) 873-8664, ext. 323 [email protected] Dan McMahon at (860) 873-8664, ext. 324 [email protected] CASTING COMPLETE FOR GOODSPEED’S MOVING NEW MUSICAL HI, MY NAME IS BEN A Modern-Day Fairytale About Communication And Connection Hi, My Name is Ben begins May 17 at The Terris Theatre EAST HADDAM, CONN., APRIL 11, 2019: Goodspeed Musicals continues its commitment to innovative, thought-provoking new works with Hi, My Name is Ben, the inspirational true story of one man who impacted the lives of all those around him without speaking a word. Written by Scott Gilmour and Claire McKenzie while in residence at the Johnny Mercer Writers Colony at Goodspeed, this hope-filled musical will run May 17 – June 9, 2019 at The Terris Theatre in Chester, CT. This production is supported in part by the Richard P. Garmany Fund at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving The true story of one ordinary man and his extraordinary life. From his tiny room in New York City, Bernhardt Wichmann III changed the lives of those around him without ever speaking a word. Using just his notepad, pen and open heart, Ben turned a neighborhood of strangers into a community of friends, before finally encountering a miracle of his own. Featuring an uplifting, folk-inflected score by award-winning Scottish writing team Noisemaker in association with Dundee Rep, one of Scotland’s leading theatres, this is the story of how one man with nothing somehow changed everything. Ben will be played by Joel Rooks, who has performed in several Broadway shows including Fish in the Dark, The Royal Family, Say Goodnight Gracie, Taller Than a Dwarf, The Tenth Man, The Sisters Rosensweig, and Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune. -

Our School Preschool Songbook

September Songs WELCOME THE TALL TREES Sung to: “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” Sung to: “Frère Jacques” Welcome, welcome, everyone, Tall trees standing, tall trees standing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the hill, on the hill, First we’ll clap our hands just so, See them all together, see them all together, Then we’ll bend and touch our toe. So very still. So very still. Welcome, welcome, everyone, Wind is blowing, wind is blowing, Now you’re here, we’ll have some fun. On the trees, on the trees, See them swaying gently, see them swaying OLD GLORY gently, Sung to: “Oh, My Darling Clementine” In the breeze. In the breeze. On a flag pole, in our city, Waves a flag, a sight to see. Sun is shining, sun is shining, Colored red and white and blue, On the leaves, on the trees, It flies for me and you. Now they all are warmer, and they all are smiling, In the breeze. In the breeze. Old Glory! Old Glory! We will keep it waving free. PRESCHOOL HERE WE ARE It’s a symbol of our nation. Sung to: “Oh, My Darling” And it flies for you and me. Oh, we're ready, Oh, we're ready, to start Preschool. SEVEN DAYS A WEEK We'll learn many things Sung to: “For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow” and have lots of fun too. Oh, there’s 7 days in a week, 7 days in a week, So we're ready, so we're ready, Seven days in a week, and I can say them all. -

For Immediate Release: May 12

For Immediate Release National Tour Press Contact: Meghan Kastenholz Local Press Contact: Haley Sheram BRAVE Public Relations 404.233.3993 [email protected] “THE BEST MUSICAL OF THIS CENTURY. Heaven on Broadway! A celebration of the privilege of living inside that improbable paradise called a musical comedy.” Ben Brantley, THE NEW YORK TIMES BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND Performances begin July 17 at the Fox Theatre Tickets go on sale Sunday, March 25 ATLANTA (March 12, 2018) – Back by popular demand, THE BOOK OF MORMON, which played a record breaking two week return engagement in 2014, as well as in 2016, returns to Atlanta for a limited run, July 17-22 at the Fox Theatre as an option to the Fifth Third Bank Broadway in Atlanta 2017/2018 season. Single tickets will go on sale Sunday, March 25. Tickets go on sale Sunday, March 25. Tickets start at $33.50 and are available by visiting FoxTheatre.org by calling 1-855-285-8499 or visiting the Fox Theatre Box Office (660 Peachtree St NE, Atlanta, GA 30308). Group orders of 10 or more may be placed by calling 404-881-2000. Performance schedule, prices and cast are subject to change without notice. For more information, please visit BookofMormonTheMusical.com or BroadwayInAtlanta.com. THE BOOK OF MORMON will play at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre July 17-22. The performance schedule is as follows: Tuesday-Thursday 7:30 p.m. Friday 8 p.m. Saturday 2 p.m., 8 p.m. Sunday 1 p.m., 6:30 p.m. THE BOOK OF MORMON features book, music and lyrics by Trey Parker, Robert Lopez and Matt Stone. -

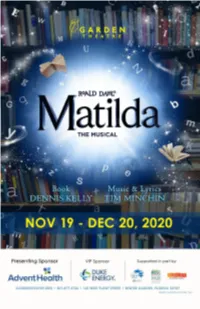

Matilda-Playbill-FINAL.Pdf

We’ve nevER been more ready with child-friendly emergency care you can trust. Now more than ever, we’re taking extra precautions to keep you and your kids safe in our ER. AdventHealth for Children has expert emergency pediatric care with 14 dedicated locations in Central Florida designed with your little one in mind. Feel assured with a child-friendly and scare-free experience available near you at: • AdventHealth Winter Garden 2000 Fowler Grove Blvd | Winter Garden, FL 34787 • AdventHealth Apopka 2100 Ocoee Apopka Road | Apopka, Florida 32703 Emergency experts | Specialized pediatric training | Kid-friendly environments 407-303-KIDS | AdventHealthforChildren.com/ER 20-AHWG-10905 A part of AdventHealth Orlando Joseph C. Walsh, Artistic Director Elisa Spencer-Kaplan, Managing Director Book by Music and Lyrics by Dennis Kelly Tim Minchin Orchestrations and Additional Music Chris Nightingale Presenting Sponsor: ADVENTHEALTH VIP Sponsor: DUKE ENERGY Matilda was first commissioned and produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and premiered at The Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, England on 9 November 2010. It transferred to the Cambridge Theatre in the West End of London on 25 October 2011 and received its US premiere at the Shubert Theatre, Broadway, USA on 4 March 2013. ROALD DAHL’S MATILDA THE MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI) All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 423 West 55th Street, New York, NY 10019 Tel: (212)541-4684 Fax: (212)397-4684 www.MTIShows.com SPECIAL THANKS Garden Theatre would like to thank these extraordinary partners, with- out whom this production of Matilda would not be possible: FX Design Group; 1st Choice Door & Millwork; Toole’s Ace Hardware; Signing Shadows; and the City of Winter Garden. -

Groundhog Day

GROUNDHOG DAY TEACHING RESOURCES JUL—S E P 2 016 CONTENTS Company 3 Old Vic New Voices Education The Old Vic The Cut Creative team 7 London SE1 8NB Character breakdown 10 E [email protected] @oldvicnewvoices Synopsis 12 © The Old Vic, 2016. All information is correct at the Themes 15 time of going to press, but may be subject to change Timeline – Musicals adapted from American and 16 Teaching resources European films Compiled by Anne Langford Design Matt Lane-Dixon Rehearsal and production Interview with illusionist and Old Vic Associate, Paul Kieve 18 photography Manuel Harlan Interview with David Birch and Carolyn Maitland, 24 Old Vic New Voices Alexander Ferris Director Groundhog Day cast members Sharon Kanolik Head of Education & Community From Screen to Stage: Considerations when adapting films to 28 Ross Crosby Community Co-ordinator stage musicals Richard Knowles Stage Business Co-ordinator A conversation with Harry Blake about songs for musicals and 30 Tom Wright Old Vic New Voices Intern plays with songs and the differences between them. Further details of this production oldvictheatre.com Practical exercises – Screen to stage 33 A day in the life of Danny Krohm, Front of House Manager 37 Bibliography and further reading 39 The Old Vic Groundhog Day teaching resource 2 COMPANY Leo Andrew David Birch Ste Clough Roger Dipper Georgina Hagen Kieran Jae Julie Jupp Andy Karl Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Ensemble Phil Connors (Jenson) (Chubby Man) (Jeff) (Deputy) (Nancy) (Fred) (Mrs Lancaster) AndrewLangtree -

Broadway Theatre

Broadway theatre This article is about the type of theatre called “Broad- The Broadway Theater District is a popular tourist at- way”. For the street for which it is named, see Broadway traction in New York City. According to The Broadway (Manhattan). League, Broadway shows sold a record US$1.36 billion For the individual theatre of this name, see Broadway worth of tickets in 2014, an increase of 14% over the pre- Theatre (53rd Street). vious year. Attendance in 2014 stood at 13.13 million, a 13% increase over 2013.[2] Coordinates: 40°45′21″N 73°59′11″W / 40.75583°N The great majority of Broadway shows are musicals. His- 73.98639°W torian Martin Shefter argues, "'Broadway musicals,' cul- minating in the productions of Richard Rodgers and Os- car Hammerstein, became enormously influential forms of American popular culture” and helped make New York City the cultural capital of the nation.[3] 1 History 1.1 Early theatre in New York Interior of the Park Theatre, built in 1798 New York did not have a significant theatre presence un- til about 1750, when actor-managers Walter Murray and Thomas Kean established a resident theatre company at the Theatre on Nassau Street, which held about 280 peo- ple. They presented Shakespeare plays and ballad op- eras such as The Beggar’s Opera.[4] In 1752, William The Lion King at the New Amsterdam Theatre in 2003, in the Hallam sent a company of twelve actors from Britain background is Madame Tussauds New York to the colonies with his brother Lewis as their manager. -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA PLAYBILL.COM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE ANNE GAREFINO SCOTT RUDIN ROGER BERLIND SCOTT M. DELMAN JEAN DOUMANIAN ROY FURMAN IMPORTANT MUSICALS STEPHANIE P. M CCLELLAND KEVIN MORRIS JON B. PLATT SONIA FRIEDMAN PRODUCTIONS EXECUTIVE PRODUCER STUART THOMPSON PRESENT BOOK, MUSIC AND LYRICS BY TREY PARKER, ROBERT LOPEZ AND MATT STONE WITH GABE GIBBS CONNER PEIRSON PJ ADZIMA MYHA’LA HERROLD STERLING JARVIS RON BOHMER OGE AGULUÉ RANDY AARON DAVID BARNES JOHNNY BRANTLEY III C HRISTOPHER BRASFIELD MELANIE BREZILL JORDAN MATTHEW BROWN BRYCE CHARLES KEVIN CLAY JAKE EMMERLING KENNY FRANCOEUR JOHN GARRY ERIC GEIL KEISHA GILLES JACOB HAREN DARYN WHITNEY HARRELL ERIC HUFFMAN K RISTEN JETER KOLBY KINDLE TYLER LEAHY WILL LEE- WILLIAMS MONICA L. PATTON CJ PAWLIKOWSKI J NYCOLE RALPH JAMARD RICHARDSON TYRONE L. ROBINSON CLINTON SHERWOOD LEONARD E. SULLIVAN BRINIE W ALLACE SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN SCOTT PASK ANN ROTH BRIAN MACDEVITT BRIAN RONAN HAIR DESIGN ORCHESTRATIONS CASTING PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER JOSH MARQUETTE LARRY HOCHMAN & CARRIE GARDNER JOYCE DAVIDSON STEPHEN OREMUS DANCE MUSIC ARRANGEMENTS MUSIC DIRECTOR MUSIC COORDINATOR ASSOCIATE PRODUCER GLEN KELLY ALAN BUKOWIECKI MICHAEL KELLER ELI BUSH TOUR BOOKING AGENCY TOUR PRESS AND MARKETING PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT GENERAL MANAGEMENT THE BOOKING ALLIED LIVE AURORA THOMPSON TURNER GROUP/ PRODUCTIONS PRODUCTIONS/ MEREDITH BLAIR ADAM J. MILLER MUSIC SUPERVISION AND VOCAL ARRANGEMENTS STEPHEN OREMUS CHOREOGRAPHED BY CASEY -

Hollywood Pantages Theatre Los Angeles, California

® HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 3.12.20 - 3.31.20 Hamilton @ Pantages LA.indd 1 2/27/20 4:29 PM HOLLYWOOD PANTAGES THEATRE March 12-March 31, 2020 Jeffrey Seller Sander Jacobs Jill Furman AND The Public Theater PRESENT BOOK, MUSIC AND LYRICS BY Lin-Manuel Miranda INSPIRED BY THE BOOK ALEXANDER HAMILTON BY Ron Chernow WITH Rubén J. Carbajal Nicholas Christopher Joanna A. Jones Taylor Iman Jones Carvens Lissaint Simon Longnight Rory O’Malley Sabrina Sloan Wallace Smith Jamael Westman AND Sam Aberman Gerald Avery Amanda Braun Cameron Burke Yossi Chaikin Trey Curtis Jeffery Duffy Karlee Ferreira Tré Frazier Aaron Alexander Gordon Sean Green, Jr. Jared Howelton Sabrina Imamura Jennifer Locke Yvette Lu Taeko McCarroll Mallory Michaellann Antuan Magic Raimone Julian Ramos Jen Sese Willie Smith III Terrance Spencer Raven Thomas Tommar Wilson Mikey Winslow Morgan Anita Wood SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN David Korins Paul Tazewell Howell Binkley Nevin Steinberg HAIR AND WIG DESIGN ARRANGEMENTS MUSIC COORDINATORS ASSOCIATE MUSIC SUPERVISOR Charles G. LaPointe Alex Lacamoire Michael Keller Matt Gallagher Lin-Manuel Miranda Michael Aarons EXECUTIVE PRODUCER PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER MUSIC DIRECTOR Maggie Brohn J. Philip Bassett Scott Rowen Andre Cerullo MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS TECHNICAL SUPERVISION CASTING Laura Matalon Hudson Theatrical Associates Telsey + Company John Gilmour Bethany Knox, CSA ASSOCIATE & SUPERVISING DIRECTOR ASSOCIATE & SUPERVISING CHOREOGRAPHER Patrick Vassel -

To Play the Music Hall 1 Week Only! November 14-19, 2017

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ellen McDonald Office - 816.444.0052 | Cell - 816.213.4355 [email protected] TO PLAY THE MUSIC HALL 1 WEEK ONLY! NOVEMBER 14-19, 2017 KANSAS CITY, MO– Broadway Across America is thrilled to announce WAITRESS will play the Music Hall for a limited 1-week engagement November 14-19, 2017. Tickets for WAITRESS are on sale now and are available online at Ticketmaster.com, at the Music Hall box office, 301 W. 13th Street, or by calling 1.800.745.3000. Groups of 10+ call 1.866.314.7687. Brought to life by a groundbreaking all-female creative team, this irresistible new hit features original music and lyrics by 6-time Grammy® nominee Sara Bareilles ("Brave," "Love Song"), a book by acclaimed screenwriter Jessie Nelson (I Am Sam) and direction by Tony Award® winner Diane Paulus (Hair, Pippin, Finding Neverland). Inspired by Adrienne Shelly's beloved film, WAITRESS tells the story of Jenna - a waitress and expert pie maker, Jenna dreams of a way out of her small town and loveless marriage. A baking contest in a nearby county and the town's new doctor may offer her a chance at a fresh start, while her fellow waitresses offer their own recipes for happiness. But Jenna must summon the strength and courage to rebuild her own life. "It's an empowering musical of the highest order!" raves the Chicago Tribune. "WAITRESS is a little slice of heaven!" says Entertainment Weekly and "a monumental contribution to Broadway!" according to Marie Claire. Don't miss this uplifting musical celebrating friendship, motherhood, and the magic of a well-made pie. -

The Abbey Activity Calendar ~ Independent Living

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 345 6 9:30 Greeting Card Workshop (RR) 10:00 Wii Bowling Queen (RR) 10:00 Wii Bowling: Terrific Four (RR) 10:30 Greeting Card Workshop (RR) 10:00 Wii Bowling Kings (RR) 10:30 Exercise w/ Oksana (RR) 10:15 Card Kit Workshop (RR) 1:00 Wii Bowling: Fri. Follies (RR) 10:00 Needle Art (hall, across from #2228) Please sign up for workshop ~ The Abbey Singles Party ~ 2:00 Musical “Kinky Boots” (PT) 1:30 Quarter Bingo (RR) 1:00 Bible Study (RR) Knitting, Crochet, Cross Stitch, Needlepoint 1:15 Quarter Bingo w/ Dale (RR) 1:30 Group 1- sign up Group 1 – sign up 3:00 Saturday Matinee (PT) 2:15 Watercolor Class (RR) 1:30 Giant Crossword Puzzle (#2212) 3:00 Ladies Wii Bowling: 2:30 Group 2- sign up 3:00 Tech Workshop (RR) Michael Feinstein “The Sinatra 2:30 Documentary “3 Nations of Texas & 2:30 Jewelry Workshop (RR) Assistance with your IPhone or IPad Bowling Beauties (RR) 3:30 Group 3- sign up Legacy” The Civil War; “Republic of Texas; 6 residents per group-sign up Group # 1- sign up 3:00 Virtual Travelogue (PT) 3:00 Men’s Billiards (BSL) Confederate State, United States”. (PT) 3:00 Men’s Billiards (BSL) 3:00 Men’s Billiards (BSL) 7:15 Evening Movie (PT) 3:00 Ice Cream Social (GS) 3:00 Men’s Billiards (BSL) 7:15 Evening Movie (PT) 7:15 Evening Movie (PT) 7:15 Evening Movie (PT) 3:00 Men’s Billiards (BSL) 7:15 Evening Movie (PT) 7:15 Movie “The Alamo” (PT) Groundhog Day Super Bowl LV 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 10:15 Card Kit Workshop (RR) 10:00 Wii Bowling: Terrific Four (RR) 10:30 Exercise w/ Oksana -

MICHAEL FATICA AEA Hair: Brown Eyes: Green Height: 5’6’’ Vocal Range: Tenor

MICHAEL FATICA AEA Hair: Brown Eyes: Green Height: 5’6’’ Vocal Range: Tenor BROADWAY The Cher Show (OBC/ current) Phil Spector/ u/s Sonny Bono d. Jason Moore/c. Chris Gattelli A Bronx Tale Vacation Swing (Doo Wops) d. Jerry Zaks/c. Sergio Trujillo Groundhog Day (OBC) Chubby Man/ Asst. DC d. Matthew Warchus/ c. Peter Darling Matilda Party Entertainer/ Ensemble d. Matthew Warchus/ c. Peter Darling She Loves Me (OBC) Busboy/ Ensemble d. Scott Ellis/ c. Warren Carlyle Disney’s Newsies (OBC) Dance Captain/ Swing d. Jeff Calhoun/ c. Chris Gattelli NY THEATRE/ NATIONAL TOUR THE STING (Pre-Broadway Premiere) Floyd d. John Rando/c. Warren Carlyle (Papermill Playhouse) Matilda 1st National Tour Ensemble/US Michael/Sergei d. Matthew Warchus/ c. Peter Darling Asst. Dance Capt/Gym Capt Matilda Interational Tour (current) Assistant Choreographer d. Matthew Warchus/ c. Peter Darling Steps In Time w/ Tommy Tune Singer/Dancer d./c. Tommy Tune (Town Hall) Radio City Spring Spectacular Assistant Choreographer d./c. Warren Carlyle (Radio City MH) Disney’s Beauty and the Beast Lefou d. Rob Roth/ c. Matt West (NETworks) CATS Male Kitten Swing d./c. Richard Stafford (Troika) REGIONAL THEATRE Elf Ensemble/ Dance Captain Papermill Playhouse- c. Josh Rhodes Gypsy` Assistant Choreographer/Ens d. Eric Woodall/ c. Michael Mindlin Guys & Dolls Harry The Horse Engeman Theatre- d. Peter Flynn Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Ensemble/ u/s Childcatcher Fulton Opera House d./c. Marc Robin Murder In Swingland Ned Westchester Broadway Theatre TV/ FILM She Loves Me Busboy/Ensemble PBS/ Broadway HD Commercial (National) Valentine/Christmas Couple Retailmenot.com Commercial (Web) Hug Couple Frito Lay/ Doritos TRAINING B.F.A.