'Wild Thing' Legend – but Williams Loaded the Bases with Hits In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

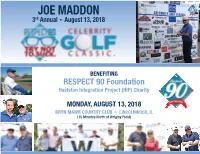

JOE MADDON 3Rd Annual • August 13, 2018

JOE MADDON 3rd Annual • August 13, 2018 TM TM BENEFITING RESPECT 90 Foundation Hazleton Integration Project (HIP) Charity MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 TM BRYN MAWR COUNTRY CLUB • LINCOLNWOOD, IL (15 Minutes North of Wrigley Field) TOURNAMENT EVENT JOE MADDON “TRY NOT TO SUCK”TM CELEBRITY GOLF CLASSIC • 2018 AUGUST 13, 2018 | BRYN MAWR COUNTRY CLUB 6600 N. CRAWFORD AVENUE-LINCOLNWOOD IL 12NOON - Shotgun Start! Day-of Schedule 9:00AM – Registration Opens, Step & Repeat, Photos, 11:40AM Continental Breakfast 9:00AM Putting Contest Begins, Live 670-AM The Score Radio Show 11:45AM Call to Carts 12NOON Shotgun Start (Lunch on Course) 4:00PM Awards Reception and Entertainment, Live Auction Jerry Lasky 312 502 8300 Steve DiMarco 818 594-7277 TM [email protected] Golf On Earth Event Services [email protected] TM SPONSORSHIP TOURNAMENT TITLE SPONSOR - $75,000 AWARDS RECEPTION SPONSOR - $5,000 • Two teams of four players plus choice of celebrity players* • Prominent Sponsor recognition on signage at Awards Reception • Prominent Title Sponsor recognition on official event materials • Prominent Sponsor recognition on official event sponsor banner (Including sponsor banner, brochure, etc.) • Reserved seating at awards reception after golf • Brand logo recognition on all tee signs • Awards Reception Sponsor recognition in tournament press • Title Sponsor recognition and signage at awards reception release and media-related opportunities • Title Sponsor recognition in tournament press release and all • Awards reception tickets (4) following play -

Go-Go to Glory

Durable Lollar found niche as White Sox anchor, run-producer By John McMurray Soft spoken and self-effacing, Sherman Lollar provided a strong defensive presence be-hind the plate during his 12 seasons with the Chicago White Sox. An All-Star catcher in seven seasons of his 18-year major-league career, Lollar won the first three American League Gold Glove awards from 1957 through 1959. Although he was not known as a power hitter, Lollar hit 155 career home runs and collected 1,415 hits. He also produced one of the White Sox’ few bright moments in the 1959 World Series apart from their Game One victory, a two-out, three-run homer that tied Game Four in the seventh inning. (Unfortunately the Sox lost that game, 5-4.) Even though Lollar played well and received awards during the 1950s, he did not receive as much national recognition as fellow catcher Yogi Berra, who won three Most Valuable Player awards. As Red Gleason wrote in The Saturday Evening Post in 1957, “It is the fate of some illustrious men to spend a career in the shadow of a contemporary. Adlai Stevenson had his Dwight Eisenhower. Lou Gehrig had his Babe Ruth. Bob Hope had his Bing Crosby. And Sherman Lollar has his Yogi Berra.” John Sherman Lollar Jr. was born on August 23, 1924, in Durham, Arkansas. His father, John Sherman Lollar Sr., had been a semipro baseball player and was a veteran of World War I. When Lollar Jr. was three years old, he moved with his family to Fayetteville, Arkansas, where his parents opened a grocery store. -

SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 2016 at NEW YORK YANKEES LH Blake Snell (ML Debut) Vs

SATURDAY, APRIL 23, 2016 at NEW YORK YANKEES LH Blake Snell (ML Debut) vs. RH Mashiro Tanaka (1-0, 3.06) First Pitch: 1:05 p.m. | Location: Yankee Stadium, Bronx, N.Y. | TV: Fox Sports Sun | Radio: WDAE 620 AM, WGES 680 AM (Sp.) Game No.: 17 (7-9) | Road Game No.: 7 (2-4) | All-Time Game No.: 2,931 (1,359-1,571) | All-Time Road Game No.: 1,462 (610-851) RAY MATTER—The Rays opened this series with a 6-3 loss last night, the for-112) in the 8th or later and .210 (87-for-414) in innings 1-through-7… AL-high 12th time they have been to 3 runs or fewer (3-9)…the Rays are 4-0 the Rays have gone into the 7th inning stretch with a lead only three times. when they score more than 3 runs…22 pct. of the Rays runs this season came in one game, Thursday’s 12-8 win at Boston…Tampa Bay is 2-2 on vs. THE A.L. BEASTS—The Rays ($57M payroll) are on a 6-game road trip this 6-game trip (2-1 at Boston and 0-1 here)…Rays have won their last two to face the Red Sox ($191M payroll) and the Yankees ($222M payroll)…since series and are 4-2 in their last 6 games…they are 7-9 for the second time in 2010, the Rays are 61-53 vs. the Red Sox and 59-53 vs. the Yankees…their the past three years…they were 8-8 a year ago…this trip starts the Rays on a 120-106 record is the AL’s best combined record vs. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Download PDF File -Omgqlhns4724

,Red Sox Jerseys NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps.Find jerseys for your favorite team or player with reasonable price from china.Wed Apr 09 09:01am EDT Morning Juice: Orioles befuddle Nolan Ryan,fall asleep regarding Rangers By David Brown This and every weekday a.ent elem why don't we rise and shine together allowing an individual the foremost fresh and reasonable major league happenings. Today's AL roll call starts in your Republic concerning Texas, where going to be the Orioles,and thus far,NBA Shorts, continue to understand more about be on the lookout nothing a little as though going to be the Dirty Birdies which of you came down 93 games last season. Game of the Day Orioles 8 Rangers 1 Anything's an improvement: Lefty Brian Burres allowed a multi functional owned or operated and pitched into going to be the 7th,mlb jerseys, helping the Birds so that you have their sixth straight. The previous a period Burres faced going to be the Rangers,person bled eight ER and 8 H at least 2/3 having to do with an inning everywhere in the Texas' 30-3 colossal drubbing perhaps going to be the on the point upon Orioles history,all the other than the 0-21 to educate yourself regarding start '88 back in the Larry Sheets days. Fo' Fo' Fo': Aubrey Huff,Suns Jerseys,nba jersey sizing,having said that celebrating his exile back and forth from Tampa Bay/St. Petersburg,steelers jersey,decided to go 4-4 with 4 RBIs, saying,customized nfl jersey, "Were relaxed. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

Comedy Theatre Arts Lectures Health

ST. LOUIS AMERICAN • DEC. 26, 2013 – JAN. 1, 2014 C3 63101. For more information, St. Louis: A Celebration Magic 100.3 Wed., Dec. 25, 12 p.m., age 11 and older to help make call (636) 527-9700 or visit through Dance. 6445 Forsyth presents Kranzberg Arts Center their baby-sitting experience a www.commitmentday.com. Blvd. # 203, 63105. For Charlie presents Stephanie Liner: success. The class will cover: more information, visit www. Wilson. See Momentos of a Doomed basic information needed Fri., Jan. 3, 7 p.m., Scottrade thebigmuddydanceco.org. CONCERTS Construct. Stephanie before you start baby-sitting, Center hosts The Harlem for details. Liner creates large orbs safety information, first- Globetrotters. 1401 Clark Sat. Jan. 19, 10 a.m., The and beautifully upholstered aid and child development. Ave., 63103. For more Pulitzer Foundation for egg shaped sculptures Each baby-sitter receives a information, visit www. the Arts presents History with windows that allow participation certificate, and harlemglobetrotters.com. of a Culture: The Real Hip the viewer to peer inside book and bag. A light snack Hop. Celebrate the history of the structure to discover a is provided. Class is taught by Sat., Jan. 4, 11 a.m., The hip-hop with a day of break beautiful girl trapped inside. St. Luke’s health educators. America’s Center hosts The dancing & street art. Watch 501 N. Grand Blvd., 63103. 222 S. Woods Mill Rd., Wedding Show. The largest Mr. Freeze, from the legendary For more information, visit 63017. For more information, wedding planning event in St. Rock Steady Crew & creator www.art-stl.com. -

The BG News April 28, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-28-1987 The BG News April 28, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 28, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4659. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4659 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 116 Bowling Green, Ohio Tuesday, April 28,1987 U.S. bars Waldheim for WWII actions WASHINGTON (AP) - Austrian States as undesirable aliens. Chancellor Franz Vranitzky would pro- Eroups that had fought to keep Wald- he would be Jailed at an immigration President Kurt Waldheim is barred Attorney General Edwin Meese ceed with a visit to the United States eim out of the United States, said in detention facility while he awaited an from entering the United States be- made the decision that found that "a planned for later this month. New York that Meese "has acted in a administrative hearing. cause he aided in the deportation and case of excludability exists with re- courageous manner and has sent a As a head of state, Waldheim would execution of thousands of Jews and spect to Kurt Waldheim as an individ- AUSTRIAN EMBASSY spokesman clear message: Nazis are not welcome normally have diplomatic immunity. -

Kit Young's Sale

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #91 1952 ROYAL STARS OF BASEBALL DESSERT PREMIUMS These very scarce 5” x 7” black & white cards were issued as a premium by Royal Desserts in 1952. Each card includes the inscription “To a Royal Fan” along with the player’s facsimile autograph. These are rarely offered and in pretty nice shape. Ewell Blackwell Lou Brissie Al Dark Dom DiMaggio Ferris Fain George Kell Reds Indians Giants Red Sox A’s Tigers EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+ $55.00 $55.00 $39.00 $120.00 $55.00 $99.00 Stan Musial Andy Pafko Pee Wee Reese Phil Rizzuto Eddie Robinson Ray Scarborough Cardinals Dodgers Dodgers Yankees White Sox Red Sox EX+ EX+ EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $265.00 $55.00 $175.00 $160.00 $55.00 $55.00 1939-46 SALUTATION EXHIBITS Andy Seminick Dick Sisler Reds Reds EX-MT EX+/EX-MT $55.00 $55.00 We picked up a new grouping of this affordable set. Bob Johnson A’s .................................EX-MT 36.00 Joe Kuhel White Sox ...........................EX-MT 19.95 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright left) .........EX-MT Ernie Lombardi Reds ................................. EX 19.00 $18.00 Marty Marion Cardinals (Exhibit left) .......... EX 11.00 Luke Appling White Sox (copyright right) ........VG-EX Johnny Mize Cardinals (U.S.A. left) ......EX-MT 35.00 19.00 Buck Newsom Tigers ..........................EX-MT 15.00 Lou Boudreau Indians .........................EX-MT 24.00 Howie Pollet Cardinals (U.S.A. right) ............ VG 4.00 Joe DiMaggio Yankees ........................... -

82Ndnbc WORLD SERIES

82ndNBC WORLD SERIES IAN KINSLER DETROIT TIGERS LIBERAL BEE JAYS 2016 NBC GRADUATE OF THE YEAR 1 NBC WORLD SERIES 2016 PROUD TO BE THE OFFICIAL BALL 2 NBC WORLD SERIES 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS NBC World Series Welcome Letters 3 NBC Staff & Board of Directors 4 Welcome to the 82nd NBC World Series! NBC History 5 On behalf of the NBC Baseball Foundation Board of Directors, I’d like to thank you for attending today’s game and sharing in this great tradition. It is my honor to serve as Chairman of this organization and to see 2016 Graduate of the Year 6-7 firsthand how the efforts of the Board have made this event stronger than ever. As a private, non-profit organization, we are dedicated to carry-on Hap Dumont’s original vision; one that provides quality baseball Former Graduates of the Year 8-9 in a family setting. The National Baseball Congress State Tournament was started in 1931 by Hap Dumont. It was originally 2016 League Affiliates 10 played on Island Park in the middle of the Arkansas River. In 1935, Hap added what has become our treasured annual event, the NBC World Series. Since then, the World Series has seen a few changes. The bats were wood, then switched to aluminum, then back to wood. The ownership of the tournament has 2016 NBC Award Sponsors 11 changed from private to public and now private. The boxcars outside the right field fence where kids used to watch the games are gone and the concourse was added. -

B a S E B a L L 2 0

2010 BASEBALL MEDIA GUIDE THE PEOPLE. THE TRADITION. THE EXCELLENCE. OHIO STATE BUCKEYES OHIO STATE BASEBALL POINTS OF PRIDE 126 3 19 15 23 Baseball is the old- Number of wins Number of NCAA Number of Big Ten All-time Big Ten est sport at Ohio head coach Bob tournament ap- Conference baseball champion- State University. Todd needs to pearances Ohio championships ships for Ohio State. The program start- reach 1,000 for State has made. – seven regular The Scarlet and ed in 1881 and the his career. Todd The total includes season and eight Gray has won 15 Big 2010 season will is Ohio State’s 13 appearances by tournaments Ten championships be the 127th in the all-time winningest coach Bob Todd’s – Ohio State has and eight Big Ten history of the sport coach with 873 Buckeye teams, won under the tournament titles. at OSU. wins in 22 sea- including 2009. direction of Bob sons. Todd. 1of 22 Ohio State is one of 10 and 3 only 22 teams to have Ohio State has had only 10 known head coaches in its 126 seasons of play won a College World and three are in the ABCA Hall of Fame: Bob Todd, Marty Karow and L.W. Series championship. St. John. The Buckeyes have competed in four Col- lege World Series. OhioStateBuckeyes.com 1 OHIO STATE BUCKEYES EDITOR Jerry Emig, Assistant Director of Athletics Communications ASSISTANT EDITOR Brett Rybak, Athletics Communications Intern ASSISTANT ATHLETICS DIRECTOR FOR EXTERNAL RELATIONS Diana Sabau LEAD GRAPHIC DESIGNER Andy DeVito THE 2010 BASEBALL GUIDE is a production of The Ohio State Athletics Communications Offi ce 2 OhioStateBuckeyes.com OHIO STATE BUCKEYES CONTENTS QUICK INFORMATION Media Information / Quick Facts ..................................