Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schencquer Review

Vol. 13, No. 1, Fall 2015, 317-330 Review/Reseña David M. K. Sheinin. Consent of the Damned: Ordinary Argentinians in the Dirty War. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. 2012. Represión y construcción de legitimidad: dimensión discursiva y monopolización del espacio público de la última dictadura militar argentina Laura Schencquer Universidad de Buenos Aires/CONICET/IDES Con un título polémico “Consent of the Damned. Ordinary Argentinians in the Dirty War” (“El consenso de los condenados. Argentinos comunes en la guerra sucia”), David Sheinin estudia en esta obra una serie de factores sociales que explican el origen y perdurabilidad de la última dictadura en Argentina (1976-1983). Como parte de los estudios de historia reciente, este trabajo se inscribe en una línea de indagación renovadora que demuestra que ningún régimen autoritario se basó exclusivamente en la represión y Schenquer 318 el miedo, sino que también dependió del consenso generado a partir de negociaciones entabladas entre la sociedad civil y el Estado.1 La originalidad del texto, y su diferencia con otros trabajos, radica en que mientras estos se ocupan de las actitudes poblacionales, este libro se concentra en el rol del Estado y en su capacidad de administrar y modelar la opinión de la población. Ello se observa, por ejemplo, en la respuesta al interrogante que inicia el texto “¿Cuán impopular fue la dictadura argentina?” (1) a partir del cual se despliega un muestreo de políticas públicas con las que las autoridades pretendieron autoerigirse en “democráticas”. Apariencia y doble discurso caracterizaron a dichas políticas que señalaban que el país se encaminaba hacia un proceso de modernización, incremento de la participación en el sistema internacional (incluso con el argumento de propiciar una política de defensa de los derechos humanos), suba del consumo y disminución de la pobreza, fin de la inestabilidad política y sobre todo supresión de la violencia y del caos político propios del período anterior al golpe de Estado de 1976. -

El Caso Timerman, El Establishment Y La Prensa Israelí Titulo Rein, Raanan

El caso Timerman, el establishment y la prensa israelí Titulo Rein, Raanan - Autor/a; Davidi, Efraim - Autor/a; Autor(es) En: Revista CICLOS en la historia, la economía y la sociedad vol. XIX, no. 38. En: (diciembre 2011). Buenos Aires : FIHES, 2011. Buenos Aires Lugar FIHES Editorial/Editor 2011 Fecha Colección Relaciones exteriores; Dictadura militar 1976-1983; Judíos; Antisemitismo; Argentina; Temas Israel; Artículo Tipo de documento "http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Argentina/iihes-uba/20141123111744/v19n38a11.pdf" URL Reconocimiento-No Comercial CC BY-NC Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar NOTAS Y COMUNICACIONES El caso Timerman, el establishment y la prensa israelí Raanan Rein y Efraim Davidi* * Universidad de Tel Aviv. Los autores agradecen al Centro Goldstein-Goren para el Estudio de las Diásporas y al Instituto Sverdlin de Historia y Cultura de América Latina, ambos de la Universidad de Tel Aviv, por su beca para la investigación que hizo posible la elaboración de este artículo, así como al Instituto de Estudios Avanzados de la Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén y al Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry de la Universidad de Emory (Atlanta, EE.UU.), donde hemos podido concluir la redacción de este artículo. El 25 de mayo de 1977, día en que la Argentina festejaba la formación de su primer gobierno patrio, la dictadura milita gobernante resolvió nombrar a un general como interventor de uno de los periódicos más influyentes del país, La Opinión. -

In Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20Th Century and During Military Rule (1976-1983)

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Honors Projects Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2021 The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983) Marcus Helble Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, and the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Helble, Marcus, "The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983)" (2021). Honors Projects. 235. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/honorsprojects/235 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Jewish “Other” in Argentina: Antisemitism, Exclusion, and the Formation of Argentine Nationalism and Identity in the 20th Century and during Military Rule (1976-1983) An Honors Paper for the Department of History By Marcus Helble Bowdoin College, 2021 ©2021 Marcus Helble Dedication To my parents, Rebecca and Joseph. Thank you for always supporting me in all my academic pursuits. And to my grandfather. Your life experiences sparked my interest in Jewish history and immigration. Thank you -

Zionist and Ardent

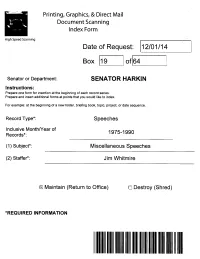

Printing, Graphics, & Direct Mail Document Scanning Index Form High Speed Scanning Date of Request: 12/01/14 Box 19 of64 Senator or Department: SENATOR HARKIN Instructions: Prepare one form for insertion at the beginning of each record series. Prepare and insert additional forms at points that you would like to index. For example: at the beginning of a new folder, briefing book, topic, project, or date sequence. Record Type*: Speeches . Inclusive Month/Year of Records*: 1975-1990 (1) Subject*: Miscellaneous Speeches (2) Staffer*: Jim Whitmire IEMaintain (Return to Office) E Destroy (Shred) *REQUIRED INFORMATION 11111111111111111111111111111111111 I / / / / INTRODUCTION OF JACOBO TIMERMAN BY U.S. REPRESENTATIVE TOM HARKIN DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE HUMAN RIGHTS AWARDS DINNER Los ANGELES OCTOBER 22, 1981 "THE PRISONER IS BLINDFOLDED, SEATED IN A CHAIR, HANDS TIED BEHIND HIM. THE ELECTRIC SHOCKS BEGIN. No QUESTIONS ARE PUT TO HIM. BUT AS HE MOANS AND JUMPS WITH THE SHOCKS, THE UNSEEN TORTURERS SPEAK INSULTS. THEN ONE SHOUTS A SINGLE WORD, AND OTHERS TAKE IT UP: 'JEW...JEW...JEW!...JEW!' AS THEY CHANT, THEY CLAP THEIR HANDS AND LAUGH. "GERMANY IN 1939? No, ARGENTINA IN 1977. WERE THE TORTURERS AN OUTLAW BAND, A GANG OF ANTI-STATE TERRORISTS? NO, THEY WERE PART OF THE STATE: MILITARY MEN FROM ONE WING OF THE ARMED FORCES THAT CONTROLLED THE ARGENTINE GOVERNMENT IN 1977 AND STILL DO. "AND THE VICTIM: WAS HE SOME UNLUCKY SOCIAL OUTCAST? No, HE WAS JACOBO TIMERMAN, EDITOR AND PUBLISHER OF A LEADING BUENOS AIRES DAILY NEWSPAPER, LA OPINION. -

Documento Completo Descargar Archivo

La embestida de la Dictadura contra el diario La Opinión. Las dos primeras intervenciones militares (1977-1978) María Marta Passaro Tram[p]as de la comunicación y la cultura, N.º 78, pp. 91-114, marzo 2016 ISSN 2314-274X | http://www.revistatrampas.com.ar FPyCS | Universidad Nacional de La Plata María Marta Passaro [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0191-0984 Centro de Estudios en Historia | Comunicación | Periodismo | Medios (CEHICOPEME) Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social Universidad Nacional de La Plata | Argentina Resumen Abstract De manera articulada con la detención y con In articulated way with the detention and la posterior expulsión de la Argentina del the later expulsion of the Argentina of the periodista Jacobo Timerman, en el artículo journalist Jacobo Timerman, in the article se analizan las dos intervenciones que sufrió there are analyzed both interventions that el diario La Opinión, en mayo y en diciembre there suffered the newspaper La Opinión, de 1977, respectivamente. En cada uno de in May and in December, 1977, respectively. estos momentos, la autora describe la situa- In each of these moments, the authoress ción de los periodistas y de los trabajadores describes the situation of the journalists and gráficos del medio –que fueron detenidos, of the graphical workers of the media –that desaparecidos e incluso asesinados–, junto were arrested, missing and even murdered– con los cambios que experimentó el matu- with the changes that the early morning tino en el espacio redaccional, en el forma- experienced in the redaccional space, in the to y en la estética: reducción de páginas e format and in the aesthetics: reduction of incorporación de suplementos, inclusión de pages and incorporation of supplements, información deportiva, aumento del espacio incorporation of sports information, and publicitario y del empleo de fotografías. -

Making Friends with Perón: Developmentalism and State Capitalism in U.S.-Argentine Relations, 1970–1975 David M

Making Friends with Perón: Developmentalism and State Capitalism in U.S.-Argentine Relations, 1970–1975 David M. K. Sheinin In February 2011, Argentine authorities seized a cache of weapons from a U.S. Air Force C-17 transport plane that had landed in Buenos Aires. In a heated media exchange, political leaders in the United States and Argentina (including Argentine Foreign Min- ister Héctor Timerman and U.S. President Barack Obama) quickly transformed the seizure into a diplomatic incident of note, each side leveling accusations and alterna- tive versions of events at the other. The Argentine media reported that authorities had found a “secret” suitcase on board containing illicit drugs. American officials coun- tered that there were weapons but no drugs on board. What Argentine authorities had found was no secret, Washington claimed. The weapons were destined for a routine joint training operation between the Grupo de Operaciones Especiales de la Policía Federal (the Special Operations Unit of the Argen- tine Federal Police) and the U.S. Army Seventh Parachute Brigade. Without ever denying the training exercise nar- rative, Argentine authorities launched a series of attacks on past and present American military influence in Latin Juan Perón returned to Argentina on June 20, 1973, from almost 20 years of exile and assumed a brief America. These ranged from the al- third presidency from October 1973 to July 1974. leged failure of the U.S. government to disclose a list of contents of the C-17 to the historic role of the School of the Amer- icas in training Latin American military officers in torture techniques. -

ARGENTINA THREE Ti Lles DURING 197 1 and the Siialler INSTI TUTIONS TIIICE

t:s~lif I !lEI: I I Ill Approved for Public Release ·· De1jnrtn1ent of.. State 8 December 2016 PI<GE ~~ BUEIIO:; 8~6H 0! OF 83 21222&Z 5763 BUENOS 9~6 5 6 91 OF 93 ACT IOU ARA·I4 HAVE RePORTED TO THE E11BASSY THA T IN MlO·JUIIE A fEtiALE INFO 'Q£l:!l ISO· GO HA·O~ TRSE-BB CIAE-OB DODE·GB PII ·B~ PSYCHOl OGIST liAS ABDUCTED BY SECURITY f ORCES ArlO HElD FOR H-91 I ~R·IS l·Ol NSA£· 09 NSC-9S PA-91 SP-82 l~ HOURS. OURI HG HER DETE~T I OH, THE PSYCHOLOGIS T, A SS·H ICA·Il Al 0·8) /078 II POL 10 VICTitl CONFINED TO A IIHEH CHA IR , liAS REPORtEDlY ------·-----------921372. 22S021Z /64 INT ERROGATE"O \liTH ELECTR IC PICAIIA REGARD IIIG THE '.!HEREABOUTS R 2121 I'Z JUL l8 AND ACTIVITIES Of ONE OF HER PATI ENTS . FM AIIENSASSY 6U[NOS AIRq 10 SECSTATE IIAS HD C 6628 LOCAl LAIIYI:R 1/HO ACCEPTS HUr,AN RIGHTS CASES REPORTED I Nf 0 AII(118ASSY ASUIIC I ON TO EMBASSY ON J (JL Y !9 THAT TH.E MOTHER OF OIIE Of HIS CL lE NTS, AMEIIBASSY 110117£V IOEO DANIE L ALBERTO EGEA, 1/HO HAS BEE II UNDE R EX£ CUTI VE DtTEIIT ION . AM( IIBASSY SAHli AGO SINCE EAR LY 1976, liAS ABDUCTED fOR FIVE DAYS IN EAR LY JULY USCINCSO QUARRY HTS BY MEN CLAI11111G TO BE FROM THE SECURITY FORCES. \ MRS. EGEA liAS B(ATEN AND THREATENED DURING HER IIHERROGATIOII IIHJCH 8 8 II F I 0 E II T I A l SECTION I OF l. -

Argentine "Dirty War" : Human Rights Law and Literature Alexander H

Golden Gate University School of Law GGU Law Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 1997 Argentine "Dirty War" : Human Rights Law and Literature Alexander H. Lubarsky Golden Gate University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/theses Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Latin American History Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Lubarsky, Alexander H., "Argentine "Dirty War" : Human Rights Law and Literature" (1997). Theses and Dissertations. Paper 35. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at GGU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of GGU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Argentine "Dirty War" : Human Rights Law and Literature By: Alexander H. Lubarsky LL.M Thesis 1997 • • • • • • • • • Golden liote lniuer-sity School of LoUJ LL.M in I nternotioonol Legal Studies Pr-ofessor- Sompong Suchor-itkul a a a a a a a a "Everyone who has worked for the struggle for human rights knows that the real enemy is silence. II - William Barkerl INTRODUCTION In 1973 Gen. Juan Domingo Peron was voted into office as President of Argentina after an 18 year exile. He died the following year in 1974 when his second wife, Isabella Peron, served as his successor. In 1976 the military overthrew Isabella Peron as part of their "calling" to restore law and order to a chaotic Argentina. To do so, the military declared an all out war on any sectors of life which could be viewed as a threat to the maintenance of military rule. -

Of Silence and Defiance: a Case Study of the Argentine Press During

Of Silence and Defiance: A Case Study of the Argentine Press during the “Proceso” of 1976-1983* Tim R Samples The University of Texas at Austin Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................3 The Argentine Press in Context…..........................................................................................4 El Proceso de Reorganización Nacional, 1976-83..................................................................9 Dangerous Journalists or Journalists In Danger?..................................................................10 Posture of the Junta: Journalism during the Proceso.............................................................12 Posture of the Press: Silence or Defiance?............................................................................14 Ford Falcons, sin patentes.....................................................................................................19 Conclusions….......................................................................................................................24 Notes…..................................................................................................................................27 .: Introduction 2 Due to a regime of strict censorship controls imposed by the military government, many Argentines were convinced that they were on the verge of winning the Falklands War of 1982, la Guerra de Malvinas, with Great Britain. Relying on information disseminated -

Immigrants of a Different Religion: Jewish Argentines

IMMIGRANTS OF A DIFFERENT RELIGION: JEWISH ARGENTINES AND THE BOUNDARIES OF ARGENTINIDAD, 1919-2009 By JOHN DIZGUN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Samuel L. Baily and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2010 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Immigrants of a Different Religion: Jewish Argentines and the Boundaries of Argentinidad, 1919-2009 By JOHN DIZGUN Dissertation Director: Samuel L. Baily This study explores Jewish and non-Jewish Argentine reactions and responses to four pivotal events that unfolded in the twentieth century: the 1919 Semana Trágica, the Catholic education decrees of the 1940s, the 1962 Sirota Affair, and the 1976-1983 Dirty War. The methodological decision to focus on four physically and/or culturally violent acts is intentional: while the passionate and emotive reactions and responses to those events may not reflect everyday political, cultural, and social norms in twentieth-century Argentine society, they provide a compelling opportunity to test the ever-changing meaning, boundaries, and limitations of argentinidad over the past century. The four episodes help to reveal the challenges Argentines have faced in assimilating a religious minority and what those efforts suggest about how various groups have sought to define and control what it has meant to be “Argentine” over time. Scholars such as Samuel Baily, Fernando DeVoto, José Moya and others have done an excellent job highlighting how Italian and Spanish immigrants have negotiated and navigated the ii competing demands of ‘ethnic’ preservation and ‘national’ integration in Argentina. -

Argentina Checklist

The History of Argentine Jewish Youth under the 1976-1983 Dictatorship as Seen Through Testimonial Literature A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of the Ohio State University By Laura M. Herbert The Ohio State University June 2007 Project Advisor: Professor Donna J. Guy, Department of History Table of Contents Acknowledgements…3 Dedication…4 Abstract…5 Introduction …6 Immigration …10 Transition in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century…15 World War II and the Jewish Community…16 Perón and Judaism…20 Creation of the State of Israel and the Institutional Jewish community…24 Post Perón…29 Adolf Eichmann…30 1970s and Jewish Youth…36 The Junta Comes to Power…36 The Government and Jewish Youth…38 The Jewish Community and the Disappeared …45 Fighting Anti-Semitism: Nueva Presencia…48 Zionism…52 The Assimilation/ Integration Debate …54 Conclusion…59 Bibliography …61 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Dr. Guy for her generous support of this project. I would also like to thank the colleges of the Arts and Sciences for their financial support, and the staffs at the IWO and AMIA archives for their help with my research and patience with my poor Spanish. Last, I want to thank Bailey, Emily, Catherine, Yoonhee and Brynn for being so supportive and putting up with the last few weeks. 3 Dedicated to all the good people who work at Bindery Prep. Mary Lou, Andy, Kris, and Cat, you are the best, thanks for four wonderful years. -

La Última Dictadura : Mejor Hablar De Ciertas Cosas

Gonzalo Martínez, Fototeca de ARGRA (Buenos Aires, 2004) (Buenos Aires, de ARGRA Fototeca Gonzalo Martínez, Foto: LA ÚLTIMA DICTADURA MEJOR NO HABLAR DE CIERTAS COSAS Presidenta de la Nación Dra. Cristina Fernández De Kirchner Jefe de Gabinete de Ministros Dr. Juan Manuel Abal Medina Ministro De Educación De La Nación Prof. Alberto E. Sileoni Secretario De Educación Lic. Jaime Perczyk Jefe De Gabinete A.S. Pablo Urquiza Subsecretario De Equidad Y Calidad Educativa Lic. Gabriel Brener 2 LA ÚLTIMA DICTADURA ¿Qué pasó durante la última dictadura? ¿Por qué se denomina “terrorismo de Estado” a ese momento histórico? ¿Qué sucedió el 24 de marzo? ¿Qué secto- res sociales apoyaron el golpe de estado? ¿Qué se propuso destruir la dicta- dura? ¿Cuál fue la reacción social ante el golpe? ¿Cuáles fueron las políticas económicas de la dictadura? Estas son algunas de las preguntas que busca responder este cuadernillo a través de información, testimonios, fuentes e imágenes. Recursos variados para acercarnos a un tema complejo y doloro- so, que provocó una herida social que aún permanece abierta. Madrugada del 24 de marzo de 1976, Plaza de Mayo, Buenos Aires. Héctor Osvaldo Vázquez. «El objetivo del proceso de Reorganización Nacional es realizar un escarmiento histórico. En la Argentina deberán morir todas las personas que sean necesarias para terminar con la subversión» (Jorge Rafael Videla, palabras dichas en Washington y reproducidas por Crónica el 9 de septiembre de 1977). El 24 de marzo de 1976 las Fuerzas Armadas protagonizaron en la Ar- gentina un nuevo golpe de Estado. Interrumpieron el mandato constitucio- nal de la entonces presidenta María Estela Martínez de Perón, quien ha- bía asumido en 1974 después del fallecimiento de Juan Domingo Perón.