Bubbles in Asset Prices by Burton G. Malkiel, Princeton University CEPS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download NI Newsletter Fall 2018

NATURAL INVESTMENT NEWS fall 2018 N º. 9 8 Divestment as a Moral Imperative by Kirbie Crowe Few stories dominated headlines this summer like the unfolding of the family separation debacle happening at the U.S.-Mexico border. As civil and political unrest worsened in some Latin American countries, the border saw a dramatic increase of families seeking asylum. Over the spring and early summer, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) forcibly separated more than 3,000 children from their parents, per the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” policy on immigration, and imprisoned them in detention centers across the country; in combination with the surge in Investing in Carbon Drawdown unaccompanied children crossing the border, the number by Sylvia Panek of children in U.S. detention centers has now ballooned to A little over one year ago, President Trump reaffirmed more than 13,000. his intention to withdraw the United States from the Paris News reports revealed images of solitary children, Climate Accord. As if on cue, an iceberg the size of Delaware huddled under thin aluminum blankets and wailing in the broke away from the Larsen C ice shelf in Antarctica, where cages of detention centers run by two private companies: temperatures have risen nearly five degrees on average over GEO Group and Corrections Corporation of America the past few decades. And Hurricane Harvey, Hurricane (referred to as “CoreCivic”); both manage private prisons Maria, and Hurricane Florence wrought unprecedented as well as ICE detention centers. Immigrant children held destruction in rapid succession upon Texas, Puerto Rico, in facilities run by these two companies have complained and North Carolina, respectively. -

Detecting Stock Market Bubbles: a Price-To-Earnings Approach

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2016 Detecting Stock Market Bubbles: A Price-to-Earnings Approach Austin F. Murphy Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Econometrics Commons, and the Finance Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Murphy, Austin F., "Detecting Stock Market Bubbles: A Price-to-Earnings Approach" (2016). Honors Theses. Paper 801. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/801 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Detecting Stock Market Bubbles: A Price-to- Earnings Approach Econometric Bubble Detection Department of Economics Author: Austin Murphy B.A. in Economics and Finance Academic Advisor: Michael Donihue Second Reader: Leonard Wolk Spring 2016 Colby College Colby College Department of Economics Spring 2016 Detecting Stock Market Bubbles Austin Murphy Abstract To this day, economists argue about the existence of stock market bubbles. The literature review for this paper observes the analysis of four reputable bubble tests in an attempt to provide ample qualitative proof for the existence of bubbles. The first obstacle for creating an effective bubble detection test is the difficulty of estimating true fundamental values for equities. Without adequate estimations for the fundamental values of equities, the deviation between actual price and fundamental price is impossible to observe or estimate. -

Recurring Storms: Weathering the Future by Understanding the Past

The Global Business Law Review Volume 1 Issue 1 Article 4 2010 Recurring Storms: Weathering the Future by Understanding the Past Robert L. Brown Ph.D. Greenebaum, Doll & McDonald Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/gblr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, and the International Trade Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Robert L. Brown Ph.D., Recurring Storms: Weathering the Future by Understanding the Past , 1 Global Bus. L. Rev. 1 (2010) available at https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/gblr/vol1/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Global Business Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECURRING STORMS: WEATHERING THE FUTURE BY UNDERSTANDING THE PAST ROBERT L. BROWN I. TULIPMANIA 1637 ................................................................... 2 A. Boom................................................................................ 2 B. Bust .................................................................................. 3 C. Aftermath ......................................................................... 3 D. Summary .......................................................................... 4 II. MISSISSIPPI SCHEME 1720 ....................................................... 4 A. Boom............................................................................... -

The 1719-20 Stock Euphoria: a Pan-European Perspective

Munich Personal RePEc Archive The 1719-20 stock euphoria: a pan-European perspective Condorelli, Stefano Center for Global Studies, Bern University July 2014 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/68652/ MPRA Paper No. 68652, posted 04 Jan 2016 09:56 UTC The 1719-20 stock euphoria: a pan-European perspective Working paper Stefano O. Condorelli Center for Global Studies, Bern University December 2015 This paper is the result of a three-years project and many persons have helped me along the way. I am grateful to Michael Aldous, William N. Goetzmann, Richard Kleer, Larry Neal, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, and Eugene White for comments and advices and for reading the first drafts of the manuscript. Many thanks also to Maurice Aymard, Leonor Costa, Peter M. G. Dickson, Rui Pedro Esteves, Bouda Etemad, Marc Flandreau, Rik Frehen, Jean-Yves Grenier, Pierre-Cyrille Hautcœur, André Holenstein, Jane Humphries, Naomi Lamoreaux, John Landon-Lane, Daniel Menning, Andrew Metrick, Patrick O’Brien, Kevin O’Rourke, Steven Pincus, Gilles Postel-Vinay, Jaime Reis, Hugh Rockoff, Geert Rouwenhorst, Thomas Späth, Carlo Taviani, François Velde, Koji Yamamoto, and participants in seminars at Oxford, LSE, Tübingen, Rutgers, Yale, and in APHES 2013, EHS 2014, EBHS 2014, ISECS 2015, WEHC 2015 conferences, for helpful comments and discussion. Further thanks to Daniel Menning and Larry Neal for generously sharing photos and transcripts of primary sources. Thank you also to the staff of all the archives consulted, in particular Alessandra Schiavon from the Archivio di Stato di Venezia, Maria Paola Niccoli from the Archivio di Stato di Torino, and Karin Borgkvist Ljung from the Riksarkivet. -

Asset Pricing Bubbles and Investor Emotions: an Empirical Analysis of the 2014 – 2016 Chinese Stock Market Bubble

Asset Pricing Bubbles and Investor Emotions: An Empirical Analysis of the 2014 – 2016 Chinese Stock Market Bubble Richard J. Taffler1 Warwick Business School, Chenyang Wang University of Birmingham, Linglu Li Independent, and Xijuan Bellotti Independent Version 2.0: 29th March 2017 Abstract Conventional economic and financial models find difficulty in explaining asset pricing bubbles in a way that is compatible with the underlying investor social and emotional processes at work. This paper empirically tests a five-stage path dependent emotionally driven model of speculative bubbles based on Minsky and Aliber and Kindleberger (2015). Specifically, we explore the nature of the powerful emotions investors are held sway by as prices shoot up and then collapse using formal content analysis of media reports and original domain-specific constructed emotion category word dictionaries. In particular, we show how emotions such as excitement and anxiety, mania and panic are associated with, and potentially help drive, speculative bubbles. We apply our model to the very recent Chinese stock market bubble and show empirically how different investor emotional states are an important factor in helping explain the dramatic movements in the Chinese market. The paper also conducts vector autoregressive (VAR) analysis and demonstrates the predictive ability of a formal empirical model fitted to investor emotions during the earlier 2005-2008 Chinese stock market bubble accurately to forecast the different stages and bursting of the 2014-2016 Chinese stock market bubble. 1 Corresponding author: Professor of Finance, Finance Group, Warwick Business School, University of Warwick, Coventry CV47AL, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: +442476524153. -

The Great Depression As a Credit Boom Gone Wrong by Barry Eichengreen* and Kris Mitchener**

BIS Working Papers No 137 The Great Depression as a credit boom gone wrong by Barry Eichengreen* and Kris Mitchener** Monetary and Economic Department September 2003 * University of California, Berkeley ** Santa Clara University BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS. Copies of publications are available from: Bank for International Settlements Press & Communications CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2003. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited. ISSN 1020-0959 (print) ISSN 1682-7678 (online) Abstract The experience of the 1990s renewed economists’ interest in the role of credit in macroeconomic fluctuations. The locus classicus of the credit-boom view of economic cycles is the expansion of the 1920s and the Great Depression. In this paper we ask how well quantitative measures of the credit boom phenomenon can explain the uneven expansion of the 1920s and the slump of the 1930s. We complement this macroeconomic analysis with three sectoral studies that shed further light on the explanatory power of the credit boom interpretation: the property market, consumer durables industries, and high-tech sectors. We conclude that the credit boom view provides a useful perspective on both the boom of the 1920s and the subsequent slump. -

The Big Bang: Stock Market Capitalization in the Long Run ?

The Big Bang: Stock Market Capitalization in the Long Run ? Dmitry Kuvshinov and Kaspar Zimmermann † April 2019 Abstract This paper presents new annual long-run stock market capitalization data for 17 advan- ced economies. Going beyond benchmark year estimates of Rajan and Zingales( 2003) reveals a striking new time series pattern: over the long run, the evolution of stock market size resembles a hockey stick. The ratio of stock market capitalization to GDP was stable between 1870 and 1980, tripled with a “big bang” in the 1980s and 1990s, and remains high to this day. We use novel data on equity returns, prices and cashflows to explore the underlying drivers of this sudden structural shift. Our first key finding is that the big bang is driven almost entirely by rising equity prices, not quantities. Net equity issuance is sizeable but relatively constant over time, and plays very little role in the short and long run dynamics of market cap. Second, this price increase is explained by a mix of higher dividend payments, and a higher valuation – or a lower discount rate – of the underlying dividend stream. Third, high market capitalization forecasts low subsequent equity returns, outperforming standard predictors such as the price-dividend ratio. Our results imply that rather than measuring financial efficiency, stock market capitalization is best used as a “Buffet indicator” of investor risk appetite. Keywords: Stock market capitalization, financial development, financial wealth, equity valuations, risk premiums, return predictability JEL classification codes: E44,G10,N10,N20,O16 ?This work is part of a larger project kindly supported by a research grant from the Bundesministerium fur¨ Bildung und Forschung (BMBF). -

“Temporary Stock Market Bubbles: Further Evidence from Germany”

“Temporary stock market bubbles: further evidence from Germany” AUTHORS Andreas Humpe Mario Zakrewski Andreas Humpe and Mario Zakrewski (2015). Temporary stock market bubbles: ARTICLE INFO further evidence from Germany. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 12(2), 33-40 RELEASED ON Monday, 22 June 2015 JOURNAL "Investment Management and Financial Innovations" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Investment Management and Financial Innovations, Volume 12, Issue 2, 2015 Andreas Humpe (UK), Mario Zakrewski (Germany) Temporary stock market bubbles: further evidence from Germany Abstract Within the framework of rational bubbles the authors examine the existence of temporary bubbles in the German equity market between 1973 and 2014. Moreover, the bubbles are distinguished between rational price bubbles and intrinsic bubbles that arise from overreaction to fundamentals. Over the last 40 years, four prolonged periods are identified with sharp price increases in the stock market that were not matched by appropriate earnings rises. The “dotcom” boom and the run-up to the 1987 stock market crash are well documented in the literature and the empirical findings support the existence of bubbles during these periods in the German stock market. While the “dotcom” exuberance indicates a rational and an intrinsic bubble, there is only evidence of an intrinsic bubble before the 1987 crash. Furthermore, the researchers are the first to report another rational bubble process between 2009 and 2011 that has not been documented in the literature before and was followed by a 32% fall in the DAX index. -

New Evidence on the First Financial Bubble

New Evidence on the First Financial Bubble Rik G. P. Frehen, Tilburg University William N. Goetzmann, Yale School of Management & NBER K. Geert Rouwenhorst, Yale School of Management June 27, 2011 Abstract The first global financial bubbles occurred in 1720 in France, Great-Britain and the Netherlands. Explanations for these linked bubbles primarily focus on the irrationality of investor speculation and the corresponding stock price behavior of two large firms: the South Sea Company in Great Britain and the Mississippi Company in France. In this paper we collect and examine a broad cross-section of security price data to evaluate the causes of the bubbles. Using newly available stock prices for British and Dutch firms in 1720, we find evidence against indiscriminate irrational exuberance and evidence in favor of speculation about fundamental financial and economic innovations in the European economy. These factors include the emergent Atlantic trade, new institutional forms of risk sharing and the innovative potential of the joint-stock company form itself. These factors ultimately had long-lasting transformative economic effects which may have been anticipated by the markets at the time. We use the cross-sectional data to test the hypothesis that the bubble in 1720 was driven by innovation by dividing the London share market into “old” and “new” economy stocks. We find that firms associated with the Atlantic trade and with the new joint-stock insurance form had the highest price increases and had return dynamics consistent with current models of "New Economy" stocks. New, high frequency data allow us to pinpoint the date of the 1720 crash and track its international propagation JEL Classifications: G01, G15, N13, N23 Acknowledgements We thank the International Center for Finance at the Yale School of Management for research and travel support. -

Tulip Mania: When Tulips Cost As Much As Houses

УДК 338.124.4 Shulga D., Yakubovich A., Piskun O. Tulip Mania: When Tulips Cost as Much as Houses Belarusian National Technical University Minsk, Belarus Crypto currencies and especially Bitcoin are the talk of У the town of late. According to Consumer News and BusinessТ Channel, the price of a single bitcoin has gone up at a faster pace than any other speculative vehicle in market history,Н as investor enthusiasm for the new medium has reached a fever pitch. Some have likened the Bitcoin craze toБ Tulip Mania, believing that the bubble is getting ready to burst. Aside from the Bitcoin bubble, thereй have been a lot of economic bubbles and subsequent crashes over the years such as, the dot com bubble, the stock-marketи bubble, the real-estate bubble, but one you may have neverр heard of is the Tulip Bulb Market Bubble of 17th century Netherlands. Tulip mania is a perfect example of a cautionaryо tale of price speculation in what is widely regarded asт the first recorded financial bubble and crash of all time [1]. The Roots of Tulipи Mania So, what is зthe story with the tulip mania? Well, as some may be aware, the tulip is a national symbol of the Netherlands. оThe country is affectionately known by some as the flowerп shop of the world. The Dutch people even took their love of tulips abroad when emigrating from their homeland, startingе up tulip festivals in places like New York and in the Рtown aptly named Holland located in the U.S. state of Michigan. -

Bubbles in History

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Quinn, William; Turner, John D. Working Paper Bubbles in history QUCEH Working Paper Series, No. 2020-07 Provided in Cooperation with: Queen's University Centre for Economic History (QUCEH), Queen's University Belfast Suggested Citation: Quinn, William; Turner, John D. (2020) : Bubbles in history, QUCEH Working Paper Series, No. 2020-07, Queen's University Centre for Economic History (QUCEH), Belfast This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/224837 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu QUCEH WORKING PAPER SERIES http://www.quceh.org.uk/working-papers BUBBLES IN HISTORY William Quinn (Queen’s University Belfast) John D. -

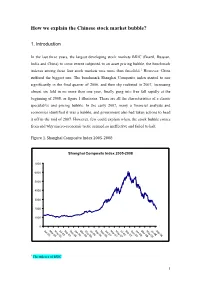

How We Explain the Chinese Stock Market Bubble?

1 However, China ese stock market bubble? pricing bubble, the benchmark oping stock markets BRIC (Brazil,cketed Russian, in 2007, increasing aracteristics of a classic ets rose more than threefold. tent subjected to an asset How we explain the Chin ment also had taken actions to head ly 2007, many a financial analysts and rter of 2006, and then sky ro 1. Introduction strates. These are all the ch ould explainso ineffective where th eand stock failed bubble to halt. comes In the last three years, the largest devel India and China) to some ex indexes among these four stock mark suffered the biggest one. The benchmark Shanghai Composite index started to rise significantly in the final qua almost six fold in no more than one year, finally gang into free fall rapidly at the beginning of 2008, as figure 1 illu speculative and pricing bubble. In the ear Sep‐08 economics identified it was a bubble, and govern Jul‐08 Shanghai Composite Index 2005-2008 May‐08 it off in the mid of 2007. However, few c Mar‐08 from and why macro-economic tactic seemed Jan‐08 Nov‐07 1 Sep‐07 Figure 1. Shanghai Composite Index 2005‐2008 Jul‐07 May‐07 Mar‐07 Jan‐07 7000 Nov‐06 Sep‐06 6000 Jul‐06 5000 May‐06 Mar‐06 4000 Jan‐06 Nov‐05 3000 Sep‐05 Jul‐05 2000 May‐05 Mar‐05 1000 0 Jan‐05 1 The indexes of BRIC Since the movement of stock prices is caused by the actions of investors, asset pricing bubbles ultimately have to be traced back to the beliefs of investors.