The Transmission of Images of Women of Color on Twitter and Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

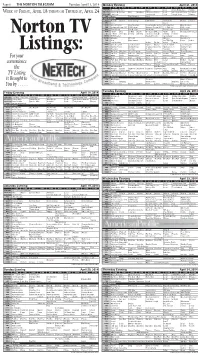

6 5-24-11 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, May 24, 2011 Monday Evening May 30, 2011 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC The Bachelorette Extreme Makeover Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , MAY 27 THROUGH THURSDAY , JUNE 2 KBSH/CBS How I Met Mad Love Two Men Mike Hawaii Five-0 Local Late Show Letterman Late KSNK/NBC Minute to Win It Law Order: CI Law & Order: LA Local Tonight Show w/Leno Late FOX House Local Cable Channels A & E Criminal Minds Criminal Minds Breakout Kings Breakout Kings Criminal Minds AMC Midway Midway ANIM River Monsters River Monsters River Monsters Finding Bigfoot River Monsters CNN CNN Presents Piers Morgan Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 Piers Morgan Tonight DISC American Chopper American Chopper Brothers Brothers American Chopper American Chopper DISN Hannah Montana Good Luck Shake It Wizards Wizards Hannah Hannah E! Khloe Khloe Khloe Khloe Khloe The Dance Chelsea E Special The Soup Chelsea Norton TV ESPN 30 for 30 30 for 30 Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NBA ESPN2 Strong Strong Strong Strong Strong Strong Strongest Man Baseball Tonight FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club My Wife My Wife FX Two Men Two Men Two Men Two Men Two Men Two Men Two Men Two Men The Ruins HGTV Hollywood at Home House Hunters Beach House Hunters House House House Hunters Beach HIST Pawn Pawn Gettysburg How the States Pawn Pawn LIFE The Perfect Teacher Vanished, Beth How I Met How I Met Chris Chris Listings: MTV Jersey Shore Jersey Shore RJ Berger RJ Berger RJ Berger RJ Berger True Life NICK My Wife My Wife Chris Chris George George The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny The Nanny SCI Underworld Underworld: Ev Ginger Snaps Back For your SPIKE Star Wars Ep 2 Star Wars: Ep. -

Toni Braxton Announces North American Fall Tour

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TONI BRAXTON ANNOUNCES NORTH AMERICAN FALL TOUR Detroit (August 8, 2016) – Seven-time GRAMMY Award-winning singer, songwriter and actress Toni Braxton announces her North American tour. Kicking off on Saturday, October 8 in Oakland, Braxton will tour more than 20 cities, ending with a show in Atlantic City, NJ on Saturday, November 12. Most recently, Braxton released “Love, Marriage & Divorce,” a duets album with Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds. The album took off behind “Hurt You,” the Urban AC #1 duet hit co-written by Toni Braxton & Babyface (with Daryl Simmons and Antonio Dixon), and produced by Babyface. The two also shared the win for Best R&B Album at the 2015 GRAMMY Awards. Today, with over 67 million in sales worldwide and seven GRAMMY Awards, Braxton is recognized as one of the most outstanding voices of this generation. Her distinctive sultry vocal blend of R&B, pop, jazz and gospel became an instantaneous international sensation when she came forth with her first solo recording in 1992. Braxton stormed the charts in the 90’s with the releases of “Toni Braxton” and “Secrets,” which spawned the hit singles and instant classics; “Another Sad Love Song,” “Breathe Again,” “You’re Makin’ Me High,” and “Unbreak My Heart.” Today, Braxton balances the demands of her career with the high priorities of family, health and public service as she raises her two sons Denim and Diezel. This year Toni was the Executive Producer of the highly-rated Lifetime movie “Unbreak My Heart” which was based on her memoir and she is the star of the WEtv hit reality series Braxton Family Values in its fifth season. -

Airgets Moreclear Inregion

Did Twitter cause the Dow This pie is to take a dive? berry good NATION & WORLD, 5A How do you make it? TASTE, 1C 807535 THE TIMES LEADER WILKES-BARRE, PA timesleader.com WEDNESDAY, APRIL 24, 2013 50¢ Machine BOSTON BOMBINGS Report: gun permit Fallen mourned in Mass. Air gets is focus of more clear county spat in region Interim sheriff refuses man’s request for a Class III permit. American Lung Association’s Collector says that’s not fair. annual assessment shows By JENNIFER LEARN-ANDES improvement in W-B area. [email protected] A Foster Township man and By ANDREW M. SEDER Luzerne County Interim Sheriff [email protected] John Robshaw are locked in a Air quality in the Scranton/ battle of wills over a permit re- Wilkes-Barre region has showed quest for a fully automatic ma- marked improvement — to the chine gun. point that a report card to be Thomas F. Braddock Jr. said issued today will reveal the re- he needs a “Class III” permit gion’s best grades in the 14-year to buy the history of the annual survey. INSIDE machine gun, The American Lung Associa- which he tion’s “State Read what wants as an in- of the Air “The air in Luzerne vestment and 2013” report County to enhance finds that the Scranton/ Council did at Tuesday’s his gun col- Scranton/ Wilkes- session lection. If the Wilkes-Barre Barre is Page 2A sheriff refuses metropolitan to grant this area has cut certainly type of permit, year-round cleaner Braddock said he will be forced and daily par- to undergo a more costly pro- ticle (soot) than when cess, hiring an attorney to pur- pollution lev- we started chase the gun through a special els since the trust. -

July-August 2018

111 The Chamber Spotlight, Saturday, July 7, 2018 – Page 1B INS IDE THIS ISSUE Vol. 10 No. 3 • July - August 2018 ALLIED MEMORIAL REMEMBRANCE RIDE FLIGHTS Of OUR FATHERS AIR SHOW AND FLY-IN NORTH TEXAS ANTIQUE TRACTOR SHOW The Chamber Spotlight General Dentistry Flexible Financing Cosmetic Procedures Family Friendly Atmosphere Sedation Dentistry Immediate Appointments 101 E. HigH St, tErrEll • 972.563.7633 • dralannix.com Page 2B – The Chamber Spotlight, Saturday, July 7, 2018 T errell Chamber of Commerce renewals April 26 – June 30 TIger Paw Car Wash Guest & Gray, P.C. Salient Global Technologies Achievement Martial Arts Academy LLC Holiday Inn Express, Terrell Schaumburg & Polk Engineers Anchor Printing Hospice Plus, Inc. Sign Guy DFW Inc. Atmos Energy Corporation Intex Electric STAR Transit B.H. Daves Appliances Jackson Title / Flowers Title Blessings on Brin JAREP Commercial Construction, LLC Stefco Specialty Advertising Bluebonnet Ridge RV Park John and Sarah Kegerreis Terrell Bible Church Brenda Samples Keith Oakley Terrell Veterinary Center, PC Brookshire’s Food Store KHYI 95.3 The Range Texas Best Pre-owned Cars Burger King Los Laras Tire & Mufflers Tiger Paw Car Wash Chubs Towing & Recovery Lott Cleaners Cole Mountain Catering Company Meadowview Town Homes Tom and Carol Ohmann Colonial Lodge Assisted Living Meridith’s Fine Millworks Unkle Skotty’s Exxon Cowboy Collection Tack & Arena Natural Technology Inc.(Naturtech) Vannoy Surveyors, Inc. First Presbyterian Church Olympic Trailer Services, Inc. Wade Indoor Arena First United Methodist Church Poetry Community Christian School WalMart Supercenter Fivecoat Construction LLC Poor Me Sweets Whisked Away Bake House Flooring America Terrell Power In the Valley Ministries Freddy’s Frozen Custard Pritchett’s Jewelry Casting Co. -

Bob Sarles Resume

Bob Sarles [email protected] (415) 305-5757 Documentary I Got A Monster Editor. True crime feature documentary. Directed by Kevin Abrams. Alpine Labs. The Nine Lives of Ozzy Osbourne Producer, editor. An A&E documentary special. Osbourne Media. Born In Chicago Co-director, Editor. Feature documentary. Shout! Factory/Out The Box Records. Mata Hari The Naked Spy Editor. Post Production Producer. Feature documentary. Red Spoke Films. BANG! The Bert Berns Story Co-director (with Brett Berns), editor. Theatrically released feature documentary. Sweet Blues: A Film About Mike Bloomfield Director, Editor. Produced by Ravin’ Films for Sony Legacy. Moon Shot Editor. Documentary series produced for Turner Original Productions and aired on TBS. Peabody Award recipient. Two Primetime Emmy nominations: editing and outstanding documentary. The Story of Fathers & Sons Editor. ABC documentary produced by Luna Productions. Unsung Editor. Documentary television series produced by A.Smith & Company for TV One. Behind The Music Producer and Editor. Documentary television series produced by VH1. Digital Divide Series Editor. PBS documentary series produced by Studio Miramar. The True Adventures of The Real Beverly Hillbillies Editor. Feature documentary. Ruckus Films. Wrestling With Satan Co-Producer, editor. Feature documentary. Wandering Eye Productions. Feed Your Head Director, editor. Documentary film produced for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland. Yo Cip! Director, Editor. Documentary short. A Ravin’ Film for Cipricious Productions. Produced by Joel Peskin. Coldplay Live! At The Fillmore Director, editor. Television series episode produced by BGP/SFX. Take Joy! The Magical World of Tasha Tudor Editor. Documentary. Aired on PBS. Spellbound Prods. Teen People Presents 21 Stars Under 21 Editor. -

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

PUBLICITY SERVICES of WYLLISA

Publicist du jour Wyllisa Bennett pictured with social icon Angela Davis at the 2013 Pan African Film Festival. Creative. Innovative. Passionate. These three words describe the person that I am, the work that I do, and my philosophy and outlook on life. Wyllisa R. Bennett, publicist du jour publicist du jour (Translation: French, publicist of the day) With more than 20 years of experience, Wyllisa Bennett has honed her skills as an award-winning writer, communicator and public relations practitioner. A North Carolina native, Wyllisa relocated to Los Angeles in 2001, and continued her career as a writer and entertainment publicist. She founded wrb public relations, a boutique public relations agency that specializes in entertainment publicity. As an entertainment publicist, Wyllisa uses her creative and communication skills to help celebrities, filmmakers, tv personalities, authors, non-profit organizations and companies achieve their public relations and marketing goals. She has worked with a plethora of award-winning actors, reality stars, personalities and household names, including reality stars NeNe Leakes (“The Real Housewives of Atlanta,” “Glee”), Alexis Bellino (“Real Housewives of Orange County”), and two-time Emmy Award-winning celebrity hairstylist Kiyah Wright (“Love in the City”); plus award-winning actors Isaiah Washington (“Grey’s Anatomy,” “The 100”), Sheryl Lee Ralph (“Moesha,” “Designing Women” and “Instant Mom”), and Victoria Rowell (“The Young and the Restless”); as well as radio personality and filmmaker Russ Parr (“The Russ Parr Show”) and radio personality and comic J. Anthony Brown (“The Tom Joyner Show” and “The Rickey Smiley Show”) – just to name a few. A native of North Carolina, she’s held positions with Community Pride magazine and The Charlotte Observer as assistant to the publisher/staff writer and special sections writer, respectively in Charlotte, North Carolina. -

Constructions of Deviance and the Performance Of

“WHAT DON’T BLACK GIRLS DO?” : CONSTRUCTIONS OF DEVIANCE AND THE PERFORMANCE OF BLACK FEMALE SEXUALITY by KIARA M. T. HILL JENNIFER SHOAFF, COMMITTEE CHAIR UTZ MCKNIGHT RACHEL RAIMIST A THESIS In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Gender and Race Studies in the Graduate School of the University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2015 Copyright Kiara Monique Hill 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This research interrogates the ways in which Black women process and negotiate their sexual identities. By connecting the historical exploitation of Black female bodies to the way Black female deviant identities are manufactured and consumed currently, I was able to show not only the evolution of Black women’s attitudes towards sexuality, but also the ways in which these attitudes manifest when policing deviancy amongst each other. Chapter 1 gives historical insight to the way that deviancy has been inextricably linked to the construction of Blackness. Using the Post-Reconstruction Era as my point of entry, I demonstrate the ways in which Black bodies were stigmatized as sexually deviant, and how the use of Black caricatures buttressed the consumption of this narrative by whites. I explain how countering this narrative became fundamental to the evolution of Black female sexual politics, and how ultimately bodily agency was later restored through sexual deviancy. Chapter 2 interrogates the way “authenticity” is propagated within the genre of reality TV. Black women are expected to perform deviant identities that coincide with controlling images so that the “authenticity” of Black womanhood is consumed by mainstream audiences. -

Scripted Stereotypes in Reality TV Paulette S

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College Summer 7-2018 Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV Paulette S. Strauss Honors College, Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Strauss, Paulette S., "Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV" (2018). Honors College Theses. 194. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/194 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUNNING HEAD: SCRIPTED STEREOTYPES IN REALITY TV Scripted Stereotypes In Reality TV Paulette S. Strauss Pace University SCRIPTED STEREOTYPES IN REALITY TV 1 Abstract Diversity, or lack thereof, has always been an issue in both television and film for years. But another great issue that ties in with the lack of diversity is misrepresentation, or a substantial presence of stereotypes in media. While stereotypes often are commonplace in scripted television and film, the possibility of stereotypes appearing in a program that claims to be based on reality seems unfitting. It is commonly known that reality television is not completely “unscripted” and is actually molded by producers and editors. While reality television should not consist of stereotypes, they have curiously made their way onto the screen and into our homes. Through content analysis this thesis focuses on Latina/Hispanic-American and Asian-American contestants on ABCs’ The Bachelor and whether they present stereotypes typically found in scripted programming. -

Peabody Is in Quite the Pickle

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 3, 2016 Peabody is in quite the pickle By Adam Swift ITEM STAFF PEABODY — It’s Friday morning at Corbeil Park, and the competitive juices are owing. Gary Pen eld twirls his racket, getting ready for mixed-doubles action with his partner, Kathy Pierce. Peter Sullivan, one of the foremost ambassadors of the game on the North Shore, rules one of the far courts. Sue Trainoff, only a year into the game, wipes the sweat from her brow. And Rob Eisenhauer sends his re- grets, taking his place on the disabled list after spraining his shoulder going for a ball earlier in the week. Tennis? Ping pong? Racquetball? While many of the athletes come from those racket sport backgrounds, what brings them to the West Peabody courts up to three times per week is pickleball, considered one of the fastest growing sports in the country. If you doubt its growing popularity, all you have to do is try to nd a parking spot on Hoover Ter- race after the games begin. “It’s a very popular sport down in the Southeast, in Florida and the Carolinas,” said Eisenhauer, who got interested PHOTOS | BOB ROCHE in the sport when he visited one of his Rob Evans, right, makes contact with a volley as his Joyce Finn, left, watches as Shirley Gallo returns a volley partner John Donovan stands at the ready during a during a pickleball match at Corbeil Park in Peabody. PICKLEBALL, A7 pickleball match at Corbeil Park. STEVE KRAUSE COMMENTARY Swampscott Harbormaster in hot water By Thor Jourgensen mine if criminal charges should be led terim harbormaster. -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed.