Research Questions for Masters Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination September 2014 SRI: Integrated Road Investment Program – Project 2 Sabaragamuwa Province Prepared by Environmental and Social Development Division, Road Development Authority, Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping for the Asian Development Bank CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 12 September 2014) Currency unit – Sri Lanka rupee (SLRe/SLRs) SLRe1.00 = $ 0.00767 $1.00 = SLR 130.300 ABBREVIATIONS ABC - Aggregate Base Coarse AC - Asphalt Concrete ADB - Asian Development Bank CBO - Community Based Organizations CEA - Central Environmental Authority DoF - Department of Forest DSDs - Divisional Secretary Divisions DOFC - Department of Forest Conservation DWLC - Department of Wild Life Conservation EC - Environmental Checklsit EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPL - Environmental Protection License ESDD - Environmental and Social Development Division FBO - Farmer Based Organizations GoSL - Government of Sri Lanka GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism GSMB - Geological Survey and Mines Bureau IEE - Initial Environmental Examination LAA - Land Acquisition Act MER - Manage Elephant Range MOHPS - Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping NAAQS - National Ambient Air Quality Standards NBRO - National Building Research Organization NEA - National Environmental Act NWS&DB- National Water Supply and Drainage Board OPRC - Output and Performance - based Road Contract PIC - Project Implementation Consultant PIU - Project Implementation Unit PRDA - Provincial Road Development Authority PS - Pradeshiya Sabha RDA - Road Development Authority ROW - Right of Way TOR - Terms of Reference NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Sri Lanka • Colombo & the Enchanted Isle

SRI LANKA • COLOMBO & THE ENCHANTED ISLE SRI LANKA The captivating island of Sri Lanka is rich in cultural and archaeological treasures spanning some 2,500 years in history - from the sacred city of Anuradhapura and the cave temples of Dambulla, to the palaces of the royal city of Kandy. It has 7 World Heritage Sites including one natural one - the Sinharaja Forest Reserve. Tea plantation © Shutterstock Polunnaruwa, which was Sri Lanka’s medieval SRI LANKA - THE capital. B ENCHANTED ISLE Day 4 Cultural Triangle Drive to Kandy, touring the Dambulla Cave 10 days/9 nights Temple and Spice Garden at Matale en route. From $2003 per person twin share Remainder of day at leisure. B Departs daily ex Colombo Day 5 Kandy Price per person from*: Cat A Cat B Cat C Excursion to the Royal Botanical Gardens at $2651 $2184 $2003 Peradeniya, a paradise for nature lovers. Later, *Based on two people sharing, singles on request. visit the Temple of the Tooth Relic, one of the INCLUSIONS world’s most sacred Buddhist sites and enjoy an Transfers, excursions in superior air-conditioned private evening traditional cultural performance. B vehicle with English speaking chauffeur guide, entrance fees, accommodation on a bed and breakfast basis, 1 bottle of water per person per day included for all surface travel. EXCLUSIONS Camera fees. A Jetwing Beach/Cinnamon Lodge/Elephant Stables/ Heritance Tea Factory/Anantara Tangalle/Kingsbury B Suriya Resort/Aliya Resort & Spa/Mahawali Reach/ Grand Hotel/Coco Tangalle/Galle Face Golden Temple of Dambulla © Shutterstock C Goldi Sands/Sigiriya Village/Amaya Hills/Jetwing St. -

Systematics and Community Composition of Foraging

J. Sci. Univ. Kelaniya 7 (2012): 55-72 OCCURRENCE AND SPECIES DIVERSITY OF GROUND-DWELLING WORKER ANTS (FAMILY: FORMICIDAE) IN SELECTED LANDS IN THE DRY ZONE OF SRI LANKA R. K. SRIYANI DIAS AND K. R. K. ANURADHA KOSGAMAGE Department of Zoology, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka ABSTRACT Ants are an essential biotic component in terrestrial ecosystems in Sri Lanka. Worker ants were surveyed in six forests, uncultivated lands and, vegetable and fruit fields in two Districts of the dry zone, Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, from November, 2007 to October, 2008 by employing several sampling methods simultaneously along five, 100 m transects. Soil sifting, litter sifting, honey-baiting and hand collection were carried out at 5 m intervals along each transect. Twenty pitfall traps were set up throughout each site and collected after five hours. Air and soil temperatures, soil pH and soil moisture at each transect were also recorded. Use of several sampling methods yielded a higher value for species richness than just one or two methods; values for each land ranged from 19 – 43 species. Each land had its own ant community and members of Amblyoponinae, Cerapachyinae, Dorylinae, Leptanillinae and Pseudomyrmecinae were recorded for the first time from the dry zone. Previous records of 40 species belonging to 23 genera in 5 subfamilies for the Anuradhapura District are updated to 78 species belonging to 36 genera in 6 subfamilies. Seventy species belonging to thirty one genera in 9 subfamilies recorded from the first survey of ants in Polonnaruwa lands can be considered a preliminary inventory of the District; current findings updated the ant species recorded from the dry zone to 92 of 42 genera in 10 subfamilies. -

Sri Lanka: Health System Enhancement Project ABBREVIATIONS

Project Administration Manual Project Number: 51107-002 Loan and Grant Number: L3727 and G0618 April 2020 Sri Lanka: Health System Enhancement Project ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank AGD Auditor General’s Department APFS audited project financial statements ATR action taken report BCCM behavior change communication and community mobilization CBSL Central Bank of Sri Lanka CIGAS computerized integrated government accounting system DMF design and monitoring framework EARF environment assessment and review framework EGM effective gender mainstreaming EMP environment management plan EMR electronic medical record ERD Department of External Resources ERTU education, training and research unit ESP essential service package FHB Family Health Bureau FHC field health center FMA financial management assessment GAP gender action plan GBV gender-based violence GOSL Government of Sri Lanka HCWM healthcare waste management HIT health information technology HPB Health Promotion Bureau HRH human resources for health HSEP Health System Enhancement Project IEC information, education and communication IHR International Health Regulations MIS management information system MOFMM Ministry of Finance and Mass Media MOH medical officer of health MOHNIM Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine MOMCH medical officer maternal and child health NCD noncommunicable disease OCB open competitive bidding PBS patient based system PCC project coordination committee PCR project completion report PDHS provincial director health services PFM public financial management PHC primary health care PHI public health inspector PHM public health midwife PHN patient healthcare number PIU project implementation unit PMCU primary medical care unit PMU project management unit POE point of entry PPER project performance evaluation report PPTA project preparatory technical assistance PSC project steering committee QCBS quality- and cost-based selection RDHS regional director of health services SOE statement of expenditure TOT training of trainers CONTENTS I. -

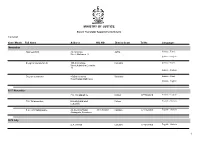

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Sri Lanka: Island Endemics and Wintering Specialties

SRI LANKA: ISLAND ENDEMICS AND WINTERING SPECIALTIES 12 – 25 JANUARY 2020 Serendib Scops Owl, discovered in 2001, is one of our endemic targets on this trip. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Sri Lanka: Island Endemics & Wintering Specialties Jan 2020 Sri Lanka is a picturesque continental island situated at the southern tip of India and has actually been connected to India for much of its geological past through episodes of lower sea level. Despite these land-bridge connections, faunal exchange between the rainforests found in Southern India and Sri Lanka has been minimal. This lack of exchange of species is probably due to the inability of rainforest organisms to disperse though the interceding areas of dry lowlands. These dry lowlands are still dry today and receive only one major rainy season, whereas Sri Lanka’s ‘wet zone’ experiences two annual monsoons. This long insularity of Sri Lankan biota in a moist tropical environment has led to the emergence of a bewildering variety of endemic biodiversity. This is why southwestern Sri Lanka and the Western Ghats of southern India are jointly regarded as one of the globe’s 34 biodiversity hotspots. Furthermore, Sri Lanka is the westernmost representative of Indo-Malayan flora, and its abundant birdlife also shows many such affinities. Sri Lanka is home to 34 currently recognized IOC endemic species with some of the most impressive ones including the rare Sri Lanka Spurfowl, gaudy Sri Lanka Junglefowl, Sri Lanka Hanging Parrot, and Layard’s Parakeet, the shy, thicket-dwelling Red-faced Malkoha, the tiny Chestnut-backed Owlet, the common Sri Lanka Grey Hornbill, Yellow- fronted Barbet, Crimson-fronted Barbet, Yellow-eared Bulbul, the spectacular Sri Lanka Blue Magpie, the cute Sri Lanka White-eye, and the tricky, but worth-the-effort trio of Sri Lanka Whistling Thrush and Sri Lanka and Spot-winged Thrushes. -

Urban Development Plan

Urban Development Plan (2018 – 2030) Urban Development Authority Sabaragamuwa Province Volume 01 RATNAPURA DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I Urban Development Authority “Sethsiripaya” Battaramulla 2018 - 2030 RATNAPURA DEVELOPMENT PLAN VOLUME I Urban Development Authority 2018 - 2030 Minister’s Foreword Local Authority Chairman’s Forward DOCUMENT INFORMATION Report Title : Ratnapura Development Plan Locational Boundary (Declared area) : Ratnapura Municipal Council Area Gazette No : Client / Stakeholder (Shortly) : Local residents of Ratnapura, Relevant Institutions, Commuters. Submission Date : 17/12/2018 Document Status : Final Document Submission Details Author UDA Ratnapura District Office Version No Details Date of Submission Approved for Issue 1 English Draft 07/12/2018 2 English Final 07/01/2019 This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above-captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from the party which commissioned it. Preface This development plan has been prepared for the implementation of the development of Ratnapura Municipal Council area within next two decades. Ratnapura town is the capital of the Ratnapura District. The Ratnapura town has a population of approximately 49,083 and act as a regional center servicing the surrounding hinterland area and providing major services including administration, education and health. -

“The Current Status of the Sinharaja Forest Reserve As a Last Viable Remnant of Sri Lanka's Tropical Low Land Rain Forest”

“The Current status of the Sinharaja forest reserve as a last viable remnant of Sri Lanka’s tropical low land rain forest” R M S U Gunathilake SC / 2006 / 6242 Level 2 Semester 2 - 1 - Dedication This book is dedicated to my parents and all teachers & other staff of Department of Zoology who does pointed several students to conserve our natural recourses to nourish future generation. - 2 - Introduction: Forest is the most valuable natural resource for any living being in the world. The key of controlling the eco-systems is also forest. There are no any human beings without flora. That means all planets where any human beings even live those who depend on the forest. All watershed areas are at the forest zone. Human and other fauna are using the recourses of forest to do meaningful their lives. Human uses the forest as building their shelters, as fire wood, for herbal, for enjoy and several tasks. After become to this technical era our natural recourses become threatened. Increasing the world population, abundance of human requirements, commercialized the human and some other things are happened to deforestation. If we unable to conserve that high valued forests or any other natural recourses then we’ll be damned by our future generation. Sinharaja is the greatest forest reserve of Sri Lanka. In today it is a world heritage. Sinharaja is a tropical low land rain forest. Tropical rain forests are the major of largest reserves of bio-diversity. They do store a vast diversity of flora and fauna. There are various endemic species can find in Sinharaja forest. -

Kalawana Gamini Central College

Site Specific Environmental and Social Management Plan (SSE & SMP) Site No. 14 Kalawana Gamini Central College Ratnapura District - Package 2 September 2018 Prepared for: Sri Lanka Landslide Mitigation Project Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) Prepared by: Environmental Studies and Services Division National Building Research Organization 99/1, Jawatta Rd Colombo 05 Tel: 011-2588946, 011-2503431, 011-22500354 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Location details and site description .................................................................................................... 1 3. Landslide hazard incident details ......................................................................................................... 2 4. Description of any remedial measures already undertaken to reduce the potential risk ...................... 4 5. Description of the area of the landslide and areas adjacent to the landslide and current level of risk . 4 6. Brief description on the surrounding environment with special reference to sensitive elements that may be affected by the project actions ................................................................................................. 5 7. Description of the works envisaged under the project ......................................................................... 5 8. Identification of social and environmental impacts and risks related to the -

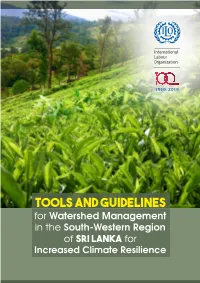

Tools and Guidelines for Watershed Management in the South

Tools and Guidelines for Watershed Management in the South-Western Region of Sri Lanka for Increased Climate Resilience TOOLS AND GUIDELINES FOR WATERSHED MANAGEMENT IN THE SOUTH-WESTERN REGION OF SRI LANKA FOR INCREASED CLIMATE RESILIENCE The research and the compilation of this document was carried out by the Environmental Foundation (Guarantee) Limited. ILO Country Office for Sri Lanka and the Maldives ii Copyright © International Labour Organization 2019 First published 2019 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licenses issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Tools and guidelines for watershed management in the South-Western region of Sri Lanka for increased climate resilience with a special focus on tea growing areas ISBN : 978-92-2-133474-3 (web pdf) International Labour Office: ILO Country Office for Sri Lanka and the Maldives Also available in Sinhala: Tools and guidelines -

The Gardens of Sri Lanka with Joe Swift

The Gardens of Sri Lanka with Joe Swift WEDNESDAY 13th MARCH 2019 With its warm climate and a rich culture, Sri Lanka is home to colourful flora, lush vegetation, amazing wildlife and a stunning collection of gardens, and this unique group tour will allow both the avid & the casual gardener the opportunity to fully explore this remarkable island in the company of BBC’s Gardener’s World presenter and garden designer Joe Swift, who will share his passion for all things floral. Aside from visits to the must-see Sigiriya Lion Rock and the Temple of the Tooth, guided tours are enjoyed in the Botanical Gardens of Henarathagoda, Peradeniya & Hakgala, and excursions made to gardens as diverse as Popham’s Arboretum, the Brief Garden & the Lunuganaga Estates. There will also be time for a tea tasting experience at a tea-estate, to explore historic Galle, to ride a traditional tuk-tuk in Kandy, to trek in the Sinharaja Forest Reserve, and to go on safari in Yala National Park. THE ITINERARY 13th March 2019: Departure Depart London Heathrow on the direct overnight non-stop flight to Colombo. 14th March 2019: Colombo On arrival, the group will be met and transferred to the tranquil Negombo Lagoon to stay overnight at the Gateway Hotel. The afternoon is free to relax and explore the hotel’s facilities and surroundings, which include a nature walk trail and the property’s own vegetable and spice garden before a visit is made to the Henarathagoda Botanical Gardens. One of the six botanical gardens in Sri Lanka and now more than 125 years old, Henarathgoda was one of the first locations used by the British in their attempts to cultivate rubber and is now home to luscious flora and over 80 species of bird. -

SRI LANKA Floods and Storms

SRI LANKA: Floods and 29 April 1999 storms Information Bulletin N° 01 The Disaster Unusually heavy rains for this time of year and violent thunderstorms along the western and south-western coast of Sri Lanka between 16 and 21 April caused widespread damage and severe floods in the south-west and south of the country. The main rivers, Kelani and Kalu, rose by over seven feet, and caused additional flooding, made worse by slow run-off. Some of the worst areas received as much as 290 mm of rain in 24 hours, and even the capital, Colombo, where 284 mm fell within 24 hours, experienced bad flooding in many sectors of the city. The worst affected districts are Ratnapura, Colombo, Kalutara, Gampaha, Galle, Kandy, Matara and Kegalle, all located between the coast and the Kandyan highlands. Six persons were reported killed by lightning, landslides or floods. Thousands of houses were damaged or destroyed, and initial official figures place the number of homeless at around 75,000 families (the average family in Sri Lanka consists of five members). In Colombo alone an estimated 12,400 families were affected. The damage is reportedly much worse in the rural areas particularly in Ratnapura District, but precise information is difficult to come by since many of the affected areas are totally cut off, with roads inundated and power and telephone lines damaged. The railway line from Colombo to Kandy has been blocked since 19 April, when boulders from a landslide damaged the tracks. FirstDistricts estimates of affected people areSub-Divisions as follows: