The Etruscan Castellum: Fortified Settlements and Regional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Proyectiles De Artillería Romana En El Oppidum De Monte Bernorio (Villarén, Palencia) Y Las Campañas De Augusto En La Primera Fase De La Guerra Cantábrica

GLADIUS Estudios sobre armas antiguas, arte militar y vida cultural en oriente y occidente XXXIII (2013), pp. 57-80 ISSN: 0436-029X doi: 10.3989/gladius.2013.0003 LOS PROYECTILES DE ARTILLERÍA ROMANA EN EL OPPIDUM DE MONTE BERNORIO (VILLARÉN, PALENCIA) Y LAS CAMPAÑAS DE AUGUSTO EN LA PRIMERA FASE DE LA GUERRA CANTÁBRICA ROMAN ARTILLERY PROJECTILES FROM THE OPPIDUM AT MONTE BERNORIO (VILLARÉN, PALENCIA) AND THE CAMPAIGNS OF AUGUSTUS IN THE EARLY PHASES OF THE CANTABRIAN WAR POR JESÚS F. TORRES -MAR T ÍNEZ (KECHU )*, AN T XO K A MAR T ÍNEZ VELASCO ** y CRIS T INA PÉREZ FARRACES *** RESU M EN - ABS T RAC T El oppidum de Monte Bernorio es conocido como una de las ciudades fortificadas de la Edad del Hierro más importantes del cantábrico. Domina una importante encrucijada de pasos a través de la Cordillera Cantábrica que per- mite la comunicación entre la submeseta norte y la zona central de la franja cantábrica. La conquista de este oppidum resultó esencial, como demuestran las recientes campañas de excavación arqueológicas, durante las campañas mili- tares que el emperador Octavio Augusto desencadenó contra Cántabros y Astures. Se presentan en este trabajo nuevas informaciones relacionadas con la conquista del núcleo por parte de las legiones romanas y de los restos de armamento localizados en las excavaciones, en especial de los proyectiles de artillería empleados en el ataque. La presencia de proyectiles de artillería de pequeño calibre indicaría el empleo de este tipo de máquinas en época altoimperial. The oppidum of Mount Bernorio is known as one of the most prominent fortified sites in the Iron Age in the Cantabrian coast. -

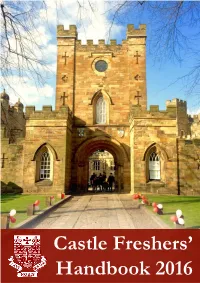

Castle Freshers' Handbook 2016

Castle Freshers’ Handbook 2016 2 Contents Welcome - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Your JCR Executive Committee - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 Your International Freshers’ Representatives - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Your Male Freshers’ Representatives - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -13 Your Female Freshers’ Representatives- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 15 Your Welfare Team - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Your Non-Executive Officers - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 21 JCR Meetings - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 24 College Site Plan - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 25 Accommodation in College - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -27 What to bring to Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -28 College Dictionary - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 29 The Key to the Lowe Library - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Social life in Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Our College’s Sports - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Our College’s Societies - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -46 Durham Students’ Union and Team Durham - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 52 General -

Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Bernard, Seth G., "Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C." (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 492. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/492 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Men at Work: Public Construction, Labor, and Society at Middle Republican Rome, 390-168 B.C. Abstract MEN AT WORK: PUBLIC CONSTRUCTION, LABOR, AND SOCIETY AT MID-REPUBLICAN ROME, 390-168 B.C. Seth G. Bernard C. Brian Rose, Supervisor of Dissertation This dissertation investigates how Rome organized and paid for the considerable amount of labor that went into the physical transformation of the Middle Republican city. In particular, it considers the role played by the cost of public construction in the socioeconomic history of the period, here defined as 390 to 168 B.C. During the Middle Republic period, Rome expanded its dominion first over Italy and then over the Mediterranean. As it developed into the political and economic capital of its world, the city itself went through transformative change, recognizable in a great deal of new public infrastructure. -

Etruscan Biophilia Viewed Through Magical Amber

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-9-2020 Etruscan Biophilia Viewed through Magical Amber Greta Rose Koshenina University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Koshenina, Greta Rose, "Etruscan Biophilia Viewed through Magical Amber" (2020). Honors Theses. 1432. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1432 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ETRUSCAN BIOPHILIA VIEWED THROUGH MAGICAL AMBER by Greta Rose Koshenina A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2020 Approved by ___________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons ___________________________________ Reader: Dr. Molly Pasco-Pranger ___________________________________ Reader: Dr. John Samonds © 2020 Greta Rose Koshenina ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis with gratitude to my advisors in both America and Italy: to Dr. Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons who endured spotty skype meetings during my semester abroad and has been a tremendous help every step of the way, to Giampiero Bevagna who helped translate Italian books and articles and showed our archaeology class necropoleis of Etruria, and to Dr. Brooke Porter who helped me see my research through the eyes of a marine biologist. -

1 Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia

Settlement Patterns in Roman Galicia: Late Iron Age – Second Century AD Jonathan Wynne Rees Thesis submitted in requirement of fulfilments for the degree of Ph.D. in Archaeology, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London University of London 2012 1 I, Jonathan Wynne Rees confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the changes which occurred in the cultural landscapes of northwest Iberia, between the end of the Iron Age and the consolidation of the region by both the native elite and imperial authorities during the early Roman empire. As a means to analyse the impact of Roman power on the native peoples of northwest Iberia five study areas in northern Portugal were chosen, which stretch from the mountainous region of Trás-os-Montes near the modern-day Spanish border, moving west to the Tâmega Valley and the Atlantic coastal area. The divergent physical environments, different social practices and political affinities which these diverse regions offer, coupled with differing levels of contact with the Roman world, form the basis for a comparative examination of the area. In seeking to analyse the transformations which took place between the Late pre-Roman Iron Age and the early Roman period historical, archaeological and anthropological approaches from within Iberian academia and beyond were analysed. From these debates, three key questions were formulated, focusing on -

Cneve Tarchunies Rumach

Classica, Sao Paulo, 718: 101-1 10, 199411995 Cneve Tarchunies Rumach R.ROSS HOLLOWAY Center for Old World Archaeology and Art Brown University RESUMO: O objetivo do Autor neste artigo e realizar um leitura historica das pinturas da Tumba Francois em Vulci, detendo-se naquilo que elas podem elucidar a respeito da sequencia dos reis romanos do seculo VI a.C. PALAVRAS CHAVE: Tumba Francois; realeza romana; uintura mural. The earliest record in Roman history, if by history we mean the union of names with events, is preserved in the paintings of an Etruscan tomb: the Francois Tomb at Vulci. The discovery of the Francois Tomb took place in 1857. The paintings were subsequently removed from the walls and became part of the Torlonia Collection in Villa Albani where they remain to this day. The decoration of the tomb, like much Etruscan funeral art, draws on Greek heroic mythology. It also included a portrait of the owner, Vel Saties, and beside him the figure of a woman named Tanaquil, presumably his wife (this figure has become almost completely illegible). In view of the group of historical personages among the tomb paintings, this name has decided resonance with better known Tanaquil, in Roman tradition the wife of Tarquinius Priscus. The historical scene of the tomb consists of five pairs of figures drawn from Etruscan and Roman history. These begin with the scene (A) Mastarna (Macstma) freeing Caeles Vibenna (Caile Vipinas) from his bonds (fig.l). There follow four scenes in three of which an armed figure dispatches an unarmed man with his sword. -

A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite? Jodi Magness University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Etruscan Studies Journal of the Etruscan Foundation Volume 8 Article 4 2001 A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite? Jodi Magness University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies Recommended Citation Magness, Jodi (2001) "A Near Eastern Ethnic Element Among the Etruscan Elite?," Etruscan Studies: Vol. 8 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/etruscan_studies/vol8/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Etruscan Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Near EasTern EThnic ElemenT Among The ETruscan EliTe? by Jodi Magness INTRODUCTION:THEPROBLEMOFETRUSCANORIGINS 1 “Virtually all archaeologists now agree that the evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of the “indigenous” theory of Etruscan origins: the development of Etruscan culture has to be understood within an evolutionary sequence of social elaboration in Etruria.” 2 “The archaeological evidence now available shows no sign of any invasion, migra- Tion, or colonisaTion in The eighTh cenTury... The formaTion of ETruscan civilisaTion occurred in ITaly by a gradual process, The final sTages of which can be documenTed in The archaeo- logical record from The ninTh To The sevenTh cenTuries BC... For This reason The problem of ETruscan origins is nowadays (righTly) relegaTed To a fooTnoTe in scholarly accounTs.” 3 he origins of the Etruscans have been the subject of debate since classical antiqui- Tty. There have traditionally been three schools of thought (or “models” or “the- ories”) regarding Etruscan origins, based on a combination of textual, archaeo- logical, and linguistic evidence.4 According to the first school of thought, the Etruscans (or Tyrrhenians = Tyrsenoi, Tyrrhenoi) originated in the eastern Mediterranean. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Ovid at Falerii

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2014 The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at Falerii Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Farrell, Joseph. (2014). “The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at alerii.F ” In D. P. Nelis and Manuel Royo (Eds.), Lire la Ville: fragments d’une archéologie littéraire de Rome antique (pp. 215–236). Bordeaux: Éditions Ausonius. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at Falerii Abstract For Ovid, erotic elegy is a quintessentially urban genre. In the Amores, excursions outside the city are infrequent. Distance from the city generally equals distance from the beloved, and so from the life of the lover. This is peculiarly true of Amores, 3.13, a poem that seems to signal the end of Ovid’s career as a literary lover and to predict his future as a poet of rituals and antiquities. For a student of poetry, it is tempting to read the landscape of such a poem as purely symbolic; and I will begin by sketching such a reading. But, as we will see, testing this reading against what can be known about the actual landscape in which the poem is set forces a revision of the results. And this revision is twofold. In the first instance, taking into account certain specific eaturf es of the landscape makes possible the correction of the particular, somewhat limited interpretive hypothesis that a purely literary reading would most probably recommend, and this is valuable in itself. -

Etruscan Winged “Demons”

First in Flight: Etruscan Winged “Demons” Marvin Morris University of California, Berkeley Classical Civilizations Class of 2016 Abstract: Etruscan winged Underworld figures (commonly referred to as winged “demons”) represent one of the most fascinating and least understood aspects of funerary iconography in ancient Etruria. Their function, along with their origin, has long been the subject of scholarly debates. However, over the last two decades, scholars have begun to take a closer look at these chthonic figures. Recent scholarship has begun to provide answers to many of the most fundamental questions concerning their role, even if disagreements remain over their murky origins. Expanding on interpretations that have cast new light on how these winged (and non winged) Underworld figures functioned, questions concerning Etruscan religious beliefs and funerary ideology can now be reconsidered. Introduction: Iconography and Ideology Etruscan winged Underworld figures (commonly referred to as winged “demons”) represent one of the most fascinating and least understood aspects of funerary iconography in ancient Etruria. Their function, along with their origin, has long been the subject of scholarly debates. However, over the last two decades, scholars1 have begun to take a closer look at these chthonic figures. Recent scholarship has begun to provide answers to many of the most fundamental questions concerning their role, even if disagreements remain over their murky origins2. Expanding on interpretations that have cast new light on how these winged (and non winged) Underworld figures functioned, questions concerning Etruscan religious beliefs and funerary ideology can now be reconsidered. One such question concerns the sudden increase in the appearance of winged “demons” that begins to occur around the end of the fifth century BCE. -

Etruscan Jewelry and Identity

Chapter 19 Etruscan Jewelry and Identity Alexis Q. Castor 1. Introduction When Etruscan jewelry is found, it is already displaced from its intended purpose. In a tomb, the typical archaeological context that yields gold, silver, ivory, or amber, the ornaments are arranged in a deliberate deposit intended for eternity. They represent neither daily nor special occasion costume, but rather are pieces selected and placed in ways that those who prepared the body, likely women, believed was significant for personal or ritual reasons. Indeed, there is no guarantee that the jewelry found on a body ever belonged to the dead. For an element of dress that the living regularly adapted to convey different looks, such permanence is entirely artificial. Today, museums house jewelry in special cases within galleries, further sep- arating the material from its original display on the body. Simply moving beyond these simu- lations requires no little effort of imagination on the part of researchers who seek to understand how Etruscans used these most personal artifacts. The approach adopted in this chapter draws on anthropological methods, especially those studies that highlight the changing self‐identity and public presentation necessary at different stages of life. As demonstrated by contemporary examples, young adults can pierce various body parts, couples exchange rings at weddings, politicians adorn their lapels with flags, and military veterans pin on medals for a parade. The wearer can add or remove all of these acces- sories depending on how he or she moves through different political, personal, economic, social, or religious settings. Cultural anthropologists who apply this theoretical framework have access to many details of life‐stage and object‐use that are lost to us. -

Fulminante-2012-Ethnicity-Chapter

- LANDSCAPE, ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY LANDSCAPE, ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY IN THE ARCHAIC MEDITERRANEAN AREA LANDSCAPE, ETHNICITY AND IDENTITY The main concern of this volume is the multi-layered IN THE ARCHAIC MEDITERRANEAN AREA concept of ethnicity. Contributors examine and contextualise contrasting definitions of ethnicity and identity as implicit in two perspectives, one from the classical tradition and another from the prehistoric and anthropological tradition. They look at the role of textual sources in reconstructing ethnicity and introduce fresh and innovative archaeological data, either from fieldwork or from new combinations of old data. Finally, in contrast to many traditional approaches to this subject, they examine the relative and interacting AREA MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAIC THE IN role of natural and cultural features in the landscape in the construction of ethnicity. The volume is headed by the contribution of Andrea Carandini whose work challenges the conceptions of many in the combination of text and archaeology. He begins by examining the mythology surrounding the founding of Rome, taking into consideration the recent archaeological evidence from the Palatine and the Forum. Here primacy is given to construction of place and mythological descent. Anthony Snodgrass, Robin Osborne, Tim Cornell and Christopher Smith offer replies to his arguments. Overall, the nineteen papers presented here show that a modern interdisciplinary and international archaeology that combines material data and textual evidence – critically – can provide a powerful lesson for the full understanding of the ideologies of ancient and modern societies G. G. C IFANI AND S. S TODDART EDITED BY ABRIELE IFANI AND IMON TODDART s G C S S Oxbow Books WITH THE SUPPORT OF SKYLAR NEIL www.oxbowbooks.com This pdf of your paper in Landscape, Ethnicity and Identity belongs to the publishers Oxbow Books and it is their copyright.