Reflections on El Salvador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

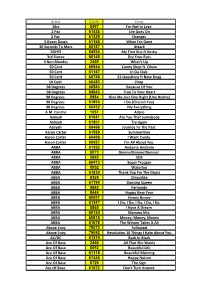

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Download the File “Tackforalltmariebytdr.Pdf”

Käraste Micke med barn, Tillsammans med er sörjer vi en underbar persons hädangång, och medan ni har förlorat en hustru och en mamma har miljoner av beundrare världen över förlorat en vän och en inspirationskälla. Många av dessa kände att de hade velat prata med er, dela sina historier om Marie med er, om vad hon betydde för dem, och hur mycket hon har förändrat deras liv. Det ni håller i era händer är en samling av över 6200 berättelser, funderingar och minnen från människor ni förmodligen inte kän- ner personligen, men som Marie har gjort ett enormt intryck på. Ni kommer att hitta både sorgliga och glada inlägg förstås, men huvuddelen av dem visar faktiskt hur enormt mycket bättre världen har blivit med hjälp av er, och vår, Marie. Hon kommer att leva kvar i så många människors hjärtan, och hon kommer aldrig att glömmas. Tack för allt Marie, The Daily Roxette å tusentals beundrares vägnar. A A. Sarper Erokay from Ankara/ Türkiye: How beautiful your heart was, how beautiful your songs were. It is beyond the words to describe my sorrow, yet it was pleasant to share life on world with you in the same time frame. Many of Roxette songs inspired me through life, so many memories both sad and pleasant. May angels brighten your way through joining the universe, rest in peace. Roxette music will echo forever wihtin the hearts, world and in eternity. And you’ll be remembered! A.Frank from Germany: Liebe Marie, dein Tod hat mich zu tiefst traurig gemacht. Ich werde deine Musik immer wieder hören. -

Roxette Golden Collection Mp3, Flac, Wma

Roxette Golden Collection mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Pop Album: Golden Collection Country: Ukraine Released: 2009 Style: Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1972 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1108 mb WMA version RAR size: 1654 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 292 Other Formats: MMF AHX AC3 MP4 MPC DTS VOC Tracklist Look Sharp! 1 –Roxette The Look 2 –Roxette Dressed For Success 3 –Roxette Sleeping Single 4 –Roxette Paint 5 –Roxette Dance Away 6 –Roxette Cry 7 –Roxette Chances 8 –Roxette Dangerous 9 –Roxette Half A Woman, Half A Shadow 10 –Roxette View From A Hill 11 –Roxette (I Could Never) Give You Up 12 –Roxette Shadow Of A Doubt 13 –Roxette Listen To Your Heart Pearls Of Passion 14 –Roxette Soul Deep 15 –Roxette Secrets That She Keeps 16 –Roxette Goodbye To You 17 –Roxette I Call Your Name 18 –Roxette Surrender 19 –Roxette Voices 20 –Roxette Neverending Love 21 –Roxette Call Of The Wild 22 –Roxette Joy Of A Toy 23 –Roxette From One Heart To Another 24 –Roxette Like Lovers Do 25 –Roxette So Far Away Dance Passion (The Remix Album) 26 –Roxette I Call Your Name (Frank Mono 7'' Mix) It Must Have Been Love (Christmas For The Broken- 27 –Roxette Hearted) 28 –Roxette Neverending Love (Tits & Ass Demo-1986) 29 –Roxette Pearls Of Passion 30 –Roxette Secrets That She Keeps (Tits & Ass Demo 1986) 31 –Roxette Turn To Me Joyride 32 –Roxette Joyride 33 –Roxette Hotblooded 34 –Roxette Fading Like A Flower (Every Time You Leave) 35 –Roxette Knockin' On Every Door 36 –Roxette Spending My Time 37 –Roxette I Remember You 38 –Roxette Watercolours -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

2013 Convention Book of Proceedings Vol I

·1 ·2 ·3 ·4· · · · · · · · · ·AMERICAN LEGION AUXILIARY ·5· · · · · · · · · · DEPARTMENT OF CALIFORNIA ·6· · · · · · · · · · ·94th ANNUAL CONVENTION ·7· · · · · · · · · · ·FRIDAY, JUNE 28, 2013 ·8· · · · · · · · · ·PALM SPRINGS, CALIFORNIA ·9 10 11 12· · · · · · · · · · · · · · VOLUME I 13· · · · · · · · · · · · ·PAGES 1 - 223 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23· ·Reported by:· Karen A. Andasola, CSR No. 10919 24 25 ·1· · · · · · · · · · · · · ·I N D E X ·2· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·PAGE ·3· ·Call to Order (Terry Mikesell)· · · · · · · · · · · ·3 · · ·Invocation (Marge Rye)· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·3 ·4· ·Roll Call (Peggy Vogele)· · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·7 · · ·Reading of Convention Rules (Barbara Davis)· · · · ·22 ·5· ·National Executive Committee Report (Linda Fercho)· 30 · · ·Chaplain Report (Marge Rye)· · · · · · · · · · · · ·38 ·6· ·Musician Report (Kat Conrad)· · · · · · · · · · · · 44 · · ·Historian Report (Carol Fuqua)· · · · · · · · · · · 45 ·7· ·Sergeant-At-Arms Report (Gloria Williams)· · · · · ·49 · · ·Convention Chairman Report (Estella Avina)· · · · · 50 ·8· ·Community Service Report · · · · · · · (Karen Karanickolas)· · · · · · · · · · · ·52 ·9· ·Legislative Report (Linda Fercho)· · · · · · · · · ·57 · · ·Americanism Report (Loretta Marsh)· · · · · · · · · 67 10· ·Department President Report (Terry Mikesell)· · · · 75 · · ·Parliamentarian Report (Ruby Kapsalis)· · · · · · · 82 11· ·Department Vice President Report (Anita Biggs)· · · 85 · · ·Secretary/Treasurer Report (Peggy Vogele)· · · · · ·89 -

2018-06-10 Edition

TODAy’s WeaTHER SUNDAY, JUNE 10, 2018 Today: Partly sunny with scattered showers and storms. HERIDAN OBLESVIllE ICERO RCADIA Tonight: Spotty S | N | C | A showers and storms. IKE TLANTA ESTFIELD ARMEL ISHERS NEWS GATHERING L & A | W | C | F PARTNER FOllOW US! HIGH: 86 LOW: 65 Fishers breaks ground on The Yard By LARRY LANNAN LarryInFishers.com The shovels were out on a hot Fishers June afternoon for the groundbreaking ceremony at the cor- ner of 116th Street and Ikea Way for The Yard development. What was originally to be only a culinary concept with a vari- ety of restaurants has expanded and will now include apartments and a 211-room Hyatt Hotel. Among the dignitaries on hand were Fishers Mayor Scott Fadness, Thompson Thrift Managing Partner Ashlee Brown Artistic rendering provided See The Yard . Page 2 This latest artist rendering from Thompson Thrift shows how The Yard will appear once completed. Noblesville Chamber of Commerce A little June Luncheon features non-profits spunk at 92 A force to be reck- From the Heart The REPORTER non-profits that support and sus- This event will also feature oned with. It's been The Noblesville Chamber of Commerce tain Noblesville by addressing the Hamilton County Leader- said about me. It has will hold its monthly luncheon from 11 a.m. the needs of the community. Each ship Academy, Noblesville Main been said about my to 1 p.m. on Wednesday, June 27. Featur- non-profit will have a table where Street, the Good Samaritan Net- mother. ing area non-profits, this luncheon will take representatives will share infor- work of Hamilton County, the At 92, every day place at Mustard Seed Gardens, 77 Metsker mation about their non-profit, its Humane Society of Hamilton my mother never Lane, Noblesville. -

English Songs List 3600 Hi

ENGLISH SONGS LIST 3600 HI code # SONG SINGER 1 40608 98.6 KEITH 2 33642 1234 FEIST 3 33643 1973 JAMES BLUNT 4 41750 5150 EDWARD VAN HALEN 5 41896 23346 FOUR SEASONS 6 33644 1 THING AMERIE 7 40085 100 POUNDS OF CLAY 8 41341 100% PURE LOVE CRYSTAL WATERS 9 40841 19 HUNDRED AND 85 PAUL MCCARTNEY 10 42188 2 BECOME 1 SPICE GIRLS 11 33645 2 HEARTS KYLIE MINOGUE 12 41860 25 MINUTES MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK 13 42709 3 A.M. MATCHBOX 20 14 43203 3 A.M. MATCHBOX 20 15 43535 3 LIONS ' 98 BADDIEL 16 43672 3 LIONS ' 98 BADDIEL 17 41515 4 + 20 CSN & Y 18 43545 5 6 7 8 CROSBY/UPTON 19 40872 500 MILES PETER/PAUL/MARY 20 41249 A BIG HUNK O' LOVE ELVIS PRESLEY 21 40625 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS 22 43365 A COLLECTION MARILLION 23 42427 A DAY IN THE LIFE THE BEATLES 24 42231 A DIFFERENT BEAT BOYZONE 25 42251 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY 26 43103 A FRIEND I CALL DESIRE ULTRAVOX 27 40493 A GAY RANCHERO VARIOUS 28 41517 A GIRL LIKE YOU EDWYN COLLINS 29 40544 A HARD DAYS NIGHT THE BEATLES 30 42613 A HAZY SHADE OF WINTER THE BANGLES 31 40501 A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA 32 40171 A HOUSE IS NOT A HOME DIONNE WARWICK 33 40172 A HUNDRED POUNDS OF CLAY GENE MC DANIELS 34 40464 A LA ORRILLA DE UN PALMA VARIOUS 35 43537 A LITLE BIT MORE AIN'T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH 36 41463 A LITTLE HELP FROM… THE BEATLES 37 42663 A LITTLE RESPECT ERASURE 38 42643 A MAN WITHOUT LOVE E. -

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam -

Pearlsofpassionyicoje

Roxette Songs - Free Printable Wordsearch PEARLSOFPASSIONYICO JEFFERSONGFUI YPANRCDSCMFOFVARATSH JPNMKZHNJYYT IFIGHOUNTYDDFDULKASP ODTJGCAKEIBB NLFWSJDGAAEWFALDKVAAE WGUWBHBVPJY MQVPATOWOJLATIRFIFC LLNDNMJKAXSRT YSBLESAYLTXMDVZASDVWG MDOYREJNCOX OKBAIESYOOOAOEJYWYBN CUOIYTYWWCXG WYJKCEZOYFCSSSIBKA ITWBISNOYPMPEP NZJNUKSGLKAZLWTZOAYQ HDLETGUXGABS WPAECEUVCUWTZEYURXGST EVANUMDUVJU ADLTNGOABFCMOUEENTAI GALSNANYOZKS YPLJRRLPLOCKHYHPIR BKXLMOUYNRTJWQ OTBXOBGHQNWMYTDJCBEI CLCAOJOYEIBV SCTHGIPVULNERABLEI TAJAMTCKZNOAMI FVJIDBLPIYXBZASTAR SLLVOICESEENLE NSBMJKAPKWKNICALLYOU RNAMEHFHDVEO XISSLUCAVHESLEEPIN GSINGLETSENIVC XLPOMXESLEEPINGINMY CARWETHTFYEAL HVMRVMYXWNSURRENDERXMXV EDIUCSWAO OEURBOOHIITTWENTYMEI YOECCOMRBFAL TRYYUVUISDUDANGEROUS LRLXYNAOJRFB BBYGJWRUHRSPEAKTOMEGT REOBGUTBOTR LLQQZLLJIETMCPUBRAN SITTTUOOVVMEX OUCBCSODCAQKLSYAYING EEHSYNSSEARH OEIDOJVKOMXUBZZSDOEG YULNNKIGTHAO DGSTOYELUDFNLOMNMLUBD AOORVRWHILA EMGJPXVPLFEBGDEATODQ EHMONVNKELLQ DEWCEILQDGRNARNTYOZR SAWRXWSOBLCW ZZQXRNSDFNIFENIOOIT UEEEBZIJTIXQV WYHIFDQPLTUVILDGAKR RRRTYJLGOGUCD IUMXZTESYKECPCHVICD IHFUNYKRCLKJT JYZOLADMANBSETIZCAF VHAPUNMHHCJIU BIG BLACK CADILLAC CRASH BOOM BANG GO TO SLEEP JEFFERSON SLEEPING IN MY CAR CINNAMON STREET SPEAK TO ME THE BIG L DO YOU GET EXCITED PLACE YOUR LOVE LITTLE GIRL THE RAIN IT S ALMOST UNREAL ALGUIEN ANYONE VULNERABLE DREAM ON ONLY WHEN I DREAM GOODBYE TO YOU DANCE AWAY THE LOOK PEARLS OF PASSION I WAS SO LUCKY REAL SUGAR CHANCES VIEW FROM A HILL IN MY OWN WAY HOTBLOODED TWENTY SPENDING MY TIME ALMOST UNREAL I M SORRY COOPER NEVERENDING -

Bowmanville Bee - Summer 2020 Bowmanville Bee Newsletter Summer 2020

Bowmanville Bee - Summer 2020 Bowmanville Bee Newsletter Summer 2020 The Bowmanville neighborhood is bordered by Foster, Rosehill Cemetery, Ravenswood and Western. Visit our website at www.bcochicago.org. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Who’s Who in the BCO A New Kind of Summer OFFICERS with the seller or builder to ask questions, and Mona Yaeger As we slide toward the end of summer, it has we notify the neighbors around that re-zoning [email protected] not been what any of us would call ideal. This is request. We create flyers with all the infor- not the summer we all hoped for, but all of us Ann Scholhamer mation, hand deliver them, and monitor any [email protected] are continuing to do our part to keep COVID- comments or replies. We also are a part of the 19 from spreading, because we know the pan- Beth Emperor rezoning calls held by the Alderman’s office. demic is not over. [email protected] In addition, we have developed and awarded Craig Hanenburg two $500 scholarships to Amundsen High School [email protected] Changing Our Events seniors heading off to college. This is our third Mike Ferraro The BCO Board has done our best to put togeth- year of awarding this scholarship, and we are Joan Frausto-Majer er events that made sense based on social dis- proud that we are able to do so because your Ron Galant tancing. We held a neighborhood spring cleanup membership dollars help fund this. Amy Gawura and a Yard-Cleanup contest, won by the neigh- Jeff Graves bors on the corner of Summerdale and Leavitt. -

Portland Daily Press: June 02,1870

The Portland Wally Press __MISCELLANEOUS. MlSCKCIiANEOCS. WAHTKU miscellaneous. Is published every day (Sundays excepted) by THE DAILY PRESS IV JEW Wanted! BAILY press. Portland Publishing Co., Itcpubliimi State Convention. ATLANTIC. dresses wanted. The citizens ot Maine who in the BUSINESS Street, Hair J. p. SMITH, rejoice progress POUixand At 10!) Exciianok Portland. DIRECTORY^ 11 d Human * '- Warehouse S ny2hd..t 100 st. Freedom and Equal RignU, achieved by 0 Dollars a Year in Carpet Exchange Terms:—Eight advaRce. 4Iii(ua 1 lie Nation under the direction ot the National and -• j We invite the attention of both Insurance AT THE City Ooiirp’y, Wanted. tEPUBLiCAN Party the last who Thursday Moraine:, June 2, 1870. (ORGANIZED IN 1842.) Boy during decade; Country readers to the following list of Port- The Maine Slate Press Spacious an«l Elegant Chambers to uo general work in a Wholesale store. icartily second the Administration of President and BUSINESS which are 51 Wall corner AJ’*'VAddress P. o. Box 2139. llw* HOUSES, among I.rllrr from st., of William, New York. iny24 Irant in its measures to secure national prosperity Along fcborr. ,ho most published every Thursday Morning at the restoration of reliable establishments in the City. if in 85 & 87 >y confidence abroad and tran- TROUT—LOBSTERS— MOUNT $2.80 a year; paid advance, at $2.00 a Injures Against Marine and Inland Navigation Risks. MIDDLE St, Boarders Wanted. DESERT—PRE- [Uilily at home; who endorse its wise policy tor the year PARATIONS FOR ItHE WATERING CAM- _ KEAZEIt BLOCK. rtENTEF.L accommodation? for a Gentleman and eduction of tiie Advertising Agency, U national debt and applaud its suc- L-omrim, is PURELY MUTUAL.