Experiences of a Sixth Grader in 1949-1950 Havana, Cuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba / by Amy Rechner

Blastoff! Discovery launches a new mission: reading to learn. Filled with facts and features, each book offers you an exciting new world to explore! This edition first published in 2019 by Bellwether Media, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Bellwether Media, Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 6012 Blue Circle Drive, Minnetonka, MN 55343. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rechner, Amy, author. Title: Cuba / by Amy Rechner. Description: Minneapolis, MN : Bellwether Media, Inc., 2019. | Series: Blastoff! Discovery: Country Profiles | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018000616 (print) | LCCN 2018001146 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626178403 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781681035819 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Cuba--Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC F1758.5 (ebook) | LCC F1758.5 .R43 2019 (print) | DDC 972.91--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018000616 Text copyright © 2019 by Bellwether Media, Inc. BLASTOFF! DISCOVERY and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Bellwether Media, Inc. SCHOLASTIC, CHILDREN’S PRESS, and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc., 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. Editor: Rebecca Sabelko Designer: Brittany McIntosh Printed in the United States of America, North Mankato, MN. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE OLD NEW WORLD 4 LOCATION 6 LANDSCAPE AND CLIMATE 8 WILDLIFE 10 PEOPLE 12 COMMUNITIES 14 CUSTOMS 16 SCHOOL AND WORK 18 PLAY 20 FOOD 22 CELEBRATIONS 24 TIMELINE 26 CUBA FACTS 28 GLOSSARY 30 TO LEARN MORE 31 INDEX 32 THE OLD NEW WORLD OLD HAVANA A family of tourists walks the narrow streets of Old Havana. -

Fidel Castro ଙ USA Miami FLORIDA Gulf of Mexico

Fidel Castro ଙ USA Miami FLORIDA Gulf of Mexico Key West Tropic of Cancer C Mariel U Havana rio Rosa del rra Sie Santa Clara Pinar del Rio Cienfuegos bray scam E Mts Sancti- Spiritus Bahia de Cochinos Isla de Pinos (Bay of Pigs) (Isle of Pines) Yucatan Basin Grand Cayman 0 100 200 km Great Abaco Island Nassau T Andros Cat Island Island H E B A H A B M Acklins A Island A S Camaguey Banes Holguin Mayari C auto Birán (birthplace of Fidel Castro) Bayamo Sierra Ma de Caimanera Turquino Sierra estra 2005m Cristal The “Granma” Santiago de Cuba landings United States base Guantánamo HAITI JAMAICA Kingston For Annette Fidel Castro ଙ A Biography Volker Skierka Translated by Patrick Camiller polity Copyright © this translation Polity Press 2004. Originally published under the title FIDEL CASTRO Eine Biografie © 2001 by Kindler Verlag GmbH Berlin (Germany) © 2001, 2004 by Volker Skierka, Hamburg (Germany) First published in 2004 by Polity Press. Polity Press 65 Bridge Street Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK Polity Press 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02148, USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Skierka, Volker, 1952– [Fidel Castro. English] Fidel Castro : a biography / Volker Skierka; translated by Patrick Camiller. -

Questions? Dr. Ken Ayers

INCLUDED IN TOUR COST: WHAT YOU ∼ All taxes NEED TO ∼ Airport transfers to and from in KNOW Havana ∼ Hotels October 7 – 14, 2017 ∼ Welcome cocktail & orientation ~Estimated cost: ∼ Meals as per itinerary $1,960 (double) or ∼ All activities, services, speakers, $2,350 (single) + meetings (excluding those airfare (R/T Nashville) noted as “optional” or “not ~Some scholarship included”) money available up to ∼ Transportation in Cuba $500 ∼ English-speaking guide & ~3 credit hours- upper translator division elective ∼ Mandatory official Cuban medical insurance coverage ~No extra tuition ∼ Emergency collect call access charge- part of your ∼ fall course load Emergency cash advances if complications occur ~Diversify your NOT INCLUDED IN TOUR COST: experiences to help IMPORTANT INFORMATION you stand out in your ∼ Airfare costs to & from Havana future career ∼ Space is limited - need verbal ∼ Cuban Tourist Card commitments ASAP ∼ Gratuities ∼ Passport costs ∼ Apply in Study Abroad Office in ∼ Spending money Library Questions? ∼ $299 non-refundable deposit required Help our students – Donate to the trip at with commitment https://www.razoo.com/story/Kwc-Cuba Dr. Ken Ayers ∼ Payment due August 30, 2017 [email protected] (45 days before departure) INS 209 International Studies (3 credits) ∼ Must have valid passport Coursework includes pre-departure and return activities, as well as reflection and Christine Salmon The Study Abroad Office will help you observation during the trip. [email protected] with applying and with financing your trip. Course can count -

The Afro-Portuguese Maritime World and The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations THE AFRO-PORTUGUESE MARITIME WORLD AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF SPANISH CARIBBEAN SOCIETY, 1570-1640 By David Wheat Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2009 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Jane G. Landers Marshall C. Eakin Daniel H. Usner, Jr. David J. Wasserstein William R. Fowler Copyright © 2009 by John David Wheat All Rights Reserved For Sheila iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been completed without support from a variety of institutions over the past eight years. As a graduate student assistant for the preservation project “Ecclesiastical Sources for Slave Societies,” I traveled to Cuba twice, in Summer 2004 and in Spring 2005. In addition to digitizing late-sixteenth-century sacramental records housed in the Cathedral of Havana during these trips, I was fortunate to visit the Archivo Nacional de Cuba. The bulk of my dissertation research was conducted in Seville, Spain, primarily in the Archivo General de Indias, over a period of twenty months in 2005 and 2006. This extended research stay was made possible by three generous sources of funding: a Summer Research Award from Vanderbilt’s College of Arts and Sciences in 2005, a Fulbright-IIE fellowship for the academic year 2005-2006, and the Conference on Latin American History’s Lydia Cabrera Award for Cuban Historical Studies in Fall 2006. Vanderbilt’s Department of History contributed to my research in Seville by allowing me one semester of service-free funding. -

The Charlotte Observer Charlotte, North Carolina 21 November 2017

U.S.-Cuba Trade and Economic Council, Inc. New York, New York Telephone (917) 453-6726 • E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cubatrade.org • Twitter: @CubaCouncil Facebook: www.facebook.com/uscubatradeandeconomiccouncil LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/company/u-s--cuba-trade-and-economic-council-inc- The Charlotte Observer Charlotte, North Carolina 21 November 2017 Nation & World US business leaders say Cuba is still open, at least to them By Franco Ordoñez WASHINGTON When the Trump administration unveiled new Cuba regulations, it sparked a fresh round of hand-wringing in Washington over the return to a posture not seen since the Cold War. But now, behind closed doors, the American business community is quietly spreading the word that things are not so different afterall. Indeed, what Trump seems to have accomplished is to make it harder for everyday Americans to meet to everyday Cubans, while leaving the doors open for corporate interests to make money on the island. “The U.S. government has actually made it easier for U.S. companies to engage directly with the Cuban private sector,” the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s U.S.-Cuba Business Council wrote in a private note to council members that was reviewed by McClatchy. “Specifically, the rule simplifies and expands the ability for U.S. companies to export directly to the Cuban private sector, private sector agricultural cooperatives and private sector entrepreneurs.” Many Republicans, including some who wanted Trump to tighten restrictions on engagement with Cuba, agree. Much of Florida’s Cuban-American congressional delegation, including Sen. Marco Rubio and Reps. -

A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico During the Renaissance and Baroque Periods Eladio Valenzuela III University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2010-01-01 A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods Eladio Valenzuela III University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Valenzuela, Eladio III, "A Survey of Choral Music of Mexico during the Renaissance and Baroque Periods" (2010). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2797. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2797 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SURVEY OF CHORAL MUSIC OF MEXICO DURING THE RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PERIODS ELADIO VALENZUELA III Department of Music APPROVED: ____________________________________ William McMillan, D.A., CHAIR ____________________________________ Elisa Fraser Wilson, D.M.A. ____________________________________ Curtis Tredway, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Allan D. McIntyre, M.Ed. _______________________________ Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School A SURVEY OF CHORAL MUSIC OF MEXICO DURING THE RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE PERIODS BY ELADIO VALENZUELA III, B.M., M.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS EL PASO MAY 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I want to thank God for the patience it took to be able to manage this project, my work, and my family life. -

Guía De La Habana Ingles.Indd

La Habana Guide Free / ENGLISH EDITORIAL BOARD Oscar González Ríos (President), Chief of Information: Mariela Freire Edition y Corrección:Infotur de La Habana, Armando Javier Díaz.y Pedro Beauballet. Design and production: MarielaTriana Images, Photomechanics Printers: PUBLICITUR Distribution: Pedro Beauballet Cover Photograph: Alfredo Saravia National Office of Tourist Information: Calle 28 No.303, e/ 3ra y 5ta,Miramar, PLaya Tel:(537) 72040624 / 72046635 www.cubatravel.cu Summary Havana, hub city 6 Attractions 8 Directory Tour Bus 27 Cuban tobacco 31 Lodgings 32 Where to Eat 43 Where to listen to music 50 Galeries and Malls 52 Sports Centers 54 Religious Institutions and Fraternal Associations 55 Museums, Theaters and Art Galeries 56 Movie Theaters, Libraries 58 Customs Regulations 60 Currency 61 Assistance and Health 64 Travel Agencies 67 Telephones 68 Embassies 70 Transport 72 Airlines 74 Events 76 To Have in Mind 78 Information centers Infotur 79 Havana Hub City Founded in 1514, the Village San Cristobal de La Habana obtained the title of city on December 1592 and in 1607 was reognized as official capital of the colony. colonial architecture, with an ample range of Arab, Spanish, Italian and Greek-latin. We assist to see a certain Architecture eclecticism, an adaptation to sensations Havana became, over 200 years ago, and desires of the island. the most important and attractive city of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, Among these creole versions, stand enchanted city for its architecture. out the portico with columns. And, less frequently, the arches that among Fronts with pilasters flanking double other formulas, show a certain liberty, doors, halfpoint arches, columns, functionality and decorative simplicity. -

STEPS to FREEDOM 2006 a Comparative Analysis of Civic Resistance in Cuba from February 2006 Through January 2007

STEPS TO FREEDOM 2006 A comparative analysis of civic resistance in Cuba from February 2006 through January 2007 Cuban Democratic Directorate Center for the Study of a National Option PASOS A LA LIBERTAD 1 Executive Editor: Janisset Rivero-Gutiérrez Editor: Dora Amador Researchers: Humberto Bustamante, Laura López, Aramís Pérez, John Suárez Copy Editors: Laura López and Marcibel Loo Data analyst and graphic production: René Carballo Transcription of recorded audio interviews: Modesto Arocha Layout: Dora Amador Cover design: Relvi Moronta Printing: Rodes Printing Translation: Alexandria Library Proof reading: John Suárez, Laura López, and Teresa Fernández Cuban Democratic Directorate is a non-profi t organization dedicated to pro- moting democratic change in Cuba and respect for human rights. As part of its work, Directorio sponsors publications and conferences in the United States, Latin America and Europe that contribute to the restoration of values of Cuban national culture and solidarity with the civic opposition on the island. The Center for the Study of a National Option is a non-profi t organiza- tion that aims to help rescue and rebuild the values, traditions, and fun- damental democratic civic concepts of the Republic of Cuba. Directorio Democrático Cubano P.O. Box 110235 Hialeah, Florida 33011 Telephone: (305) 220-1713 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.directorio.org ©2007 Directorio Democrático Cubano 2 INDEX Main achievements of the Cuban civic resistance movement in 2006 4 A nation that dreams, stands up, and fi ghts for freedom 5 A critical look at the pro-democracy movement in Cuba 7 Development of nonviolent civic actions in 2006 10 Classifi cation of non-violent actions 11 Total acts of nonviolent civic resistance from 1997 to 2006 13 Comparison of civic resistance actions by province 1 4 Commemorative dates and number of actions 18 Acts of civic resistance by month 19 PASOS A LA LIBERTAD 3 Main achievements of the Cuban civic resistance movement in 2006 • Carried out 2,768 nonviolent civic actions. -

National Association for Music Education Guest Program to Cuba February 5 – 10, 2018

National Association for Music Education Guest Program to Cuba February 5 – 10, 2018 www.professionalsabroad.org Spend an exciting week in Havana where you will Day 1 have opportunity to explore the “Gem of the Depart on individual flights to Jose Marti Caribbean” at your desired pace. Enjoy breakfast and International Airport, Havana, Cuba. Upon arrival, dinner alongside delegates, and have the freedom to transfer to the hotel, Meliá Cohiba for check-in. This eat lunch while out exploring the city. In lieu of evening, gather for an informational briefing and scheduled activities, guests are encouraged to explore introduction, followed by a welcome dinner in Old the city based on their individual interests. Cuba is Havana a paladar, or privately owned restaurant. filled with rich history, unique architecture, . remarkable museums, incredible art, music, and more. Days 2 – 5 It is recommended that you purchase a tour book to Breakfast is available daily at the hotel. Day 2, join the learn more about Cuba and its offerings. Consider the delegation for a walking tour through Old Havana. following to help get you started on your travel plans Enjoy the rest of Day 2 and subsequent days at in Cuba… leisure. Each night, except for Day 4, enjoy dinner at a paladar, or privately owned restaurant, with the delegates. On Day 5, gather in the evening for a Get acquainted with Cuba by exploring Old Havana, farewell reception and dinner in Havana. a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the heart of Havana’s colonial history. Learn about the Cuban Day 6 Revolution at Museo de la Revolución, and admire Transfer to Jose Marti International Airport, Havana, the impressive Baroque style architecture of the Cuba for individual flights home. -

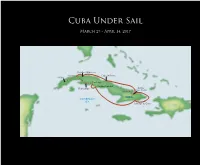

Cuba Under Sail

Cuba Under Sail March 29 - April 14, 2017 Varadero/Matanzas Havana Cayo Guillermo Viñales Cienfuegos Casilda/Trinidad Playa Larga Antilla/ Cayo Saetia Gibara CUBA CARIBBEAN SEA Santiago de Cuba Wednesday & Thursday, March 29 & 30, 2017 Depart Home / Miami / Havana, Cuba Hot sun moderated by soft breeze greeted us in Miami, a preview for conditions on the two-week voyage awaiting us. Many of us were already acquainted from previous Zegrahm trips, and Expedition Leader Nadia Eckhardt soon began introductions and a briefing. The next morning, our flight path followed the fragile low-lying chain of the Florida Keys before making the 90-mile crossing to land in Havana. Staff beckoned us to our buses, where local guides Abel Valdes and David Camps greeted us warmly. Once underway, they showed themselves to be both personable and knowledgeable, as well as forthcoming about their own histories and opinions, and the realities, dilemmas, and challenges that face Cuba. We stopped for a photo-op at the Plaza de la Revolucion, once the open- air gathering place for tens of thousands of Fidel Castro’s supporters held captivated by his masterful oratory. But our group, the majority of whom were Americans “of a certain age,” were spellbound instead by a gleaming array of 1950’s Detroit cars lined up adjacent to our parked buses. In Old Havana, Sloppy Joe’s supplied us with the first of many “welcome mojitos” and hearty lunches, before we crossed the street to a fleet of gorgeous convertibles drawn up to the curb ready to whisk us on a tour. -

Havana Guide Activities Activities

HAVANA GUIDE ACTIVITIES ACTIVITIES Partagas Cigar Factory / Real Fabrica de Tabacos Partagas Havana Cathedral / Catedral de la Habana A D A tour through factory takes you back to 1930's. It makes you appreciate Very atmospheric cathedral, no matter it is day or night. Dedicated to Saint the working conditions of Europe or America. Christopher and seat of the Cardinal Archbishop of Havana at the same time. Calle Industria 520, Havana, Cuba GPS: N23.13465, W82.36053 GPS: N23.14138, W82.35192 Opening hours: Phone: Tours are available every 15 minutes. +53 7 861 5213 Daily: 9:30 a.m. – 11 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. – 3 p.m. Opening hours: Admission: From early morning till 12 a.m. General admission: CUC 10 Open daily, but often can be locked. Admission: Admission to the cathedral is free. Old Havana / La Habana Vieja B The old Havana is a fascinating place. Since the city was founded in 1519, it's been shaped by various influences. Discover its unique charm, smell Bacardi Building / Edificio Bacardí E and tastes! Famous art deco landmark, opened in 1930. Go upstairs for a view and get some mojito or cubanito in little bar. GPS: N23.13564, W82.35117 Avenida Bélgica, Havana, Cuba GPS: N23.13884, W82.35723 National Capital Building / The Capitolio C Opening hours: Very imposing neoclassical building, built to resemble U.S. Capitol. Served Only the café and the restaurant are open to public. as the seat of the legislature until the late 1950s. Café Barrita: daily 9 a.m. – 6 p.m. -

Regla, Cuba Sister City Delegation 2013

Richmond, CA – Regla, Cuba Sister City Delegation 2013 Tom Butt, Richmond City Council Member January 7, 2014 Contents Sister City Program........................................................................................................................................ 3 Why do we have sister cities, and why should Richmond participate? The following is from Sister Cities International: ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Perceptions ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Sister City Relationship ............................................................................................................................. 5 The Delegation .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Organizations and Terminology ................................................................................................................ 6 Day by Day .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Day One – Wednesday-Thursday December 4-5 (Havana) .....................................................................