American Behavioral Scientist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Versatile Fox Sports Broadcaster Kenny Albert Continues to Pair with Biggest Names in Sports

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Erik Arneson, FOX Sports Wednesday, Sept. 21, 2016 [email protected] VERSATILE FOX SPORTS BROADCASTER KENNY ALBERT CONTINUES TO PAIR WITH BIGGEST NAMES IN SPORTS Boothmates like Namath, Ewing, Palmer, Leonard ‘Enhance Broadcasts … Make My Job a Lot More Fun’ Teams with Former Cowboy and Longtime Broadcast Partner Daryl ‘Moose’ Johnston and Sideline Reporter Laura Okmin for FOX NFL in 2016 With an ever-growing roster of nearly 250 teammates (complete list below) that includes iconic names like Joe Namath, Patrick Ewing, Jim Palmer, Jeremy Roenick and “Sugar Ray” Leonard, versatile FOX Sports play-by-play announcer Kenny Albert -- the only announcer currently doing play-by-play for all four major U.S. sports (NFL, MLB, NBA and NHL) -- certainly knows the importance of preparation and chemistry. “The most important aspects of my job are definitely research and preparation,” said Albert, a second-generation broadcaster whose long-running career behind the sports microphone started in high school, and as an undergraduate at New York University in the late 1980s, he called NYU basketball games. “When the NFL season begins, it's similar to what coaches go through. If I'm not sleeping, eating or spending time with my family, I'm preparing for that Sunday's game. “And when I first work with a particular analyst, researching their career is definitely a big part of it,” Albert added. “With (Daryl Johnston) ‘Moose,’ for example, there are various anecdotes from his years with the Dallas Cowboys that pertain to our games. When I work local Knicks telecasts with Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier on MSG, a percentage of our viewers were avid fans of Clyde during the Knicks’ championship runs in 1970 and 1973, so we weave some of those stories into the broadcasts.” As the 2016 NFL season gets underway, Albert once again teams with longtime broadcast partner Johnston, with whom he has paired for 10 seasons, sideline reporter Laura Okmin and producer Barry Landis. -

John W. Shrader

JOHN W. SHRADER 2107 Stone Creek Loop S Lincoln, NE 68512 408.910.4510 [email protected] Current Position Associate Professor, Broadcasting and Sports Media Coordinator, Sports Media and Communication College of Journalism and Mass Communications University of Nebraska-Lincoln Specialties and Research Areas of Interest Broadcast Journalism, Sports Broadcasting, Sports Journalism, Writing and Reporting, Social Media, Sport in American Culture, Sport and the Immigrant Experience, Presentation and Representation in the Media, Ethics Education M.S., Mass Communications San Jose State University B.A., Broadcast Journalism University of Nebraska – Lincoln Teaching Experience Associate Professor, Broadcasting and Sports Media University of Nebraska-Lincoln (2017-present) (Teaching Sports Writing, Sports Broadcasting, Introduction to Sports Media, Sport and American Culture, News and Broadcast Capstone) Assistant Professor, Journalism and Broadcasting California State University, Long Beach (2011-2017) promoted to Associate before leaving (Taught Television News, Sports Writing, News Writing, Investigative Reporting, Media and Society, Advisor for KBeach Radio) Lecturer / Adjunct (2007-2011) San Jose State University, Menlo College, San Francisco State University, San Jose City College (Taught Media and Society, Beginning News Writing, Sports Reporting, Television News) Awards and Honors Best of Competition, Sports Radio BEA 2019 “Sport and the Immigrant Experience in Small Town Nebraska” First Place, Outstanding Graduate Research San Jose -

Fox Sports Highlights – 3 Things You Need to Know

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014 FOX SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW NFL: Philadelphia Hosts Washington and Dallas Meets St. Louis in Regionalized Matchups COLLEGE FOOTBALL: No. 4 Oklahoma Faces West Virginia in Big 12 Showdown on FOX MLB: AL Central Battle Between Tigers and Royals, Plus Dodgers vs. Cubs in FOX Saturday Baseball ******************************************************************************************************* NFL DIVISIONAL MATCHUPS HIGHLIGHT WEEK 3 OF THE NFL ON FOX The NFL on FOX continues this week with five regionalized matchups across the country, highlighted by three divisional matchups, as the Philadelphia Eagles host the Washington Redskins, the Detroit Lions welcome the Green Bay Packers, and the San Francisco 49ers play at the Arizona Cardinals. Other action this week includes the Dallas Cowboys at St. Louis Rams and Minnesota Vikings at New Orleans Saints. FOX Sports’ NFL coverage begins each Sunday on FOX Sports 1 with FOX NFL KICKOFF at 11:00 AM ET with host Joel Klatt and analysts Donovan McNabb and Randy Moss. On the FOX broadcast network, FOX NFL SUNDAY immediately follows FOX NFL KICKOFF at 12:00 PM ET with co-hosts Terry Bradshaw and Curt Menefee alongside analysts Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Jimmy Johnson, insider Jay Glazer and rules analyst Mike Pereira. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 GAME PLAY-BY-PLAY/ANALYST/SIDELINE COV. TIME (ET) Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles Joe Buck, Troy Aikman 24% 1:00PM & Erin Andrews Lincoln Financial Field – Philadelphia, Pa. MARKETS INCLUDE: Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, Raleigh, Charlotte, Hartford, Greenville, West Palm Beach, Norfolk, Greensboro, Richmond, Knoxville Green Bay Packers at Detroit Lions Kevin Burkhardt, John Lynch 22% 1:00PM & Pam Oliver Ford Field – Detroit, Mich. -

Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’S Concussion Problem

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2016 No More Mind Games: Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’s Concussion Problem Jeffrey Parker Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Policy Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Public Relations and Advertising Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sports Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Jeffrey, "No More Mind Games: Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’s Concussion Problem" (2016). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1800. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1800 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No More Mind Games: Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’s Concussion Problem by Jeffrey Parker B.A. (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2013 THESIS Submitted to the Department of Criminology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts in Criminology Wilfrid Laurier University © Jeffrey Parker 2015 ii Abstract American (gridiron) football played at the professional level in the National Football League (NFL) is an inherently physical spectator sport, in which players frequently engage in significant contact to the head and upper body. -

The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES WINNERS OF 32 nd ANNUAL SPORTS EMMY® AWARDS Al Michaels Honored with Lifetime Achievement Award New York, NY – May 2, 2011 – The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) announced the winners tonight of the 32 nd Annual Sports Emmy® Awards at a special ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City. Winners in 33 categories including outstanding live sports special, live series, sports documentary, studio show, promotional announcements, play-by-play personality and studio analyst were honored. The awards were presented by a distinguished group of sports figures and television personalities including Cris Collinsworth (sports analyst for NBC’s “Sunday Night Football”); Dan Hicks ( NBC’s Golf host); Jim Nantz (lead play-by-play announcer of The NFL on CBS and play-by-play broadcaster for NCAA college basketball and golf on CBS); Vern Lundquist (CBS Sports play-by-play broadcaster); Chris Myers (FOX Sports Host); Scott Van Pelt (anchor, ESPN’s Sportscenter and ESPN’s radio show, “The Scott Van Pelt Show”); Hannah Storm (anchor on the weekday morning editions of ESPN’s SportsCenter); Mike Tirico (play-by-play announcer for ESPN's NFL Monday Night Football, and golf on ABC); Bob Papa (HBO Sports Broadcaster); Andrea Kremer (Correspondent, HBO’s “Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel”); Ernie Johnson (host of Inside the NBA on TNT); Cal Ripken, Jr. (TNT Sports Analyst and member of Baseball’s Hall of Fame); Ron Darling (TNT & TBS MLB Analyst and former star, NY Mets); Hazel Mae (MLB Network host, “Quick Pitch”); Steve Mariucci (Former NFL Coach and NFL Network Analyst); Marshall Faulk (Former NFL Running Back and NFL Network Analyst); and Harold Reynolds (MLB Network Studio Analyst). -

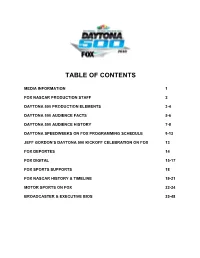

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

Daytona 500 Audience History ______17

Table of Contents Media Information ____________________________________________________2 Photography _________________________________________________________3 Production Staff ______________________________________________________4 Production Details __________________________________________________5 - 6 Valentine’s Day Daytona 500 Tale of the Tape _____________________________ 7 FOXSports.com at Daytona_____________________________________________ 8 NASCAR ON FOX Social Media _________________________________________ 9 Fox Sports Radio at Daytona _______________________________________10 – 11 FOX Sports Supports: Ronald McDonald House ___________________________12 NASCAR on FOX: 10th Season & Schedule ____________________________ 13-14 Daytona 500 & Sprint Cup Audience Facts____________________________ 15 - 16 Daytona 500 Audience History _________________________________________17 Broadcaster Biographies ___________________________________________18-27 MEDIA INFORMATION This guide has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of the Daytona 500 on FOX and is accurate as of Feb. 8, 2010. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information, photographs and facilitate interview requests. NASCAR on FOX photography, featuring Darrell Waltrip, Larry McReynolds, Mike Joy, Jeff Hammond, Chris Myers, Dick Berggren, Steve Byrnes, Krista Voda and Matt Yocum, is available on FOXFlash.com. Releases on FOX Sports’ NASCAR programming are available on www.msn.foxsports.com -

KNRO Sports Radio Media

KKNNRROO SSppoorrttss RRaaddiioo MMeeddiiaa KKiitt Redding Radio 3360 Alta Mesa Drive Redding, CA 96002 (530)226-9500 Fax (530)722-9480 Finally. Finally, all the great coverage, attitude and personality of FOX Sports comes to radio. FOX Sports Radio Network brings you the very best in personality radio targeted to Men 25–49. Delivering more than just stats and box scores, FOX Sports Radio serves up sports talk from industry veterans who know what your listeners want to hear: * Passionate opinions and in-depth coverage from seasoned professionals * Insightful commentary from the experts * Exclusive interviews and access to today’s hottest players, coaches and owners * Enthusiastic callers and lively discussions * All the topics that matter to today’s guy Fox Sports Radio – Weekdays Steve Czaban with Scott Linn M-F 3am-6am Steve Czaban presides over the quintessential morning show for the male sports fan. Is it sports? Of course. But it's also a lot more. Things like female eye candy, gambling, electronics, office politics, random yada yada, pop culture, and “all the news that matters to Czabe.” Steve Czaban starts the day, going fearlessly into sports topics few shows dare to explore. Dan Patrick M-F 6am-9am The multi-media star brings years of broadcast experience to the airwaves. Dan is joined each day by the biggest names in sports, including names like Kobe Bryant, David Stern, Bret Favre, etc. No show in sports radio attracts a more impressive lineup of guests. Jim Rome M-F 9am-12noon Not only is California native Jim Rome a “phenomenal” on-air personality, a substantive case could effortlessly be constructed he’s among a handful of the medium’s most influential broadcasters of at least the last quarter century. -

Championship-New Orleans.Pub

NEW ORLEANS SAINTS WEEKLY MEDIA INFORMATION GUIDE NFC CHAMPIONSHIP LOS ANGELES RAMS VS. NEW ORLEANS SAINTS JANUARY 20, 2019 @ MERCEDESBENZ SUPERDOME GAME INFORMATION • ROSTERS • DEPTH CHART • TEAM AND PLAYER STATISTICS LOS ANGELES RAMS (13-3, 1-0) VS. NEW ORLEANS SAINTS (13-3, 1-0) SUNDAY, JANUARY 20, 2019 – 2:05 PM (CST) MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME – NEW ORLEANS, LA. TV: FOX (WVUE FOX 8 locally) – Joe Buck (play-by-play), Troy Aikman (color analyst), Erin Andrews and Chris Myers (sideline) LOCAL RADIO: WWL (870 AM and 105.3 FM) – Zach Strief (play-by-play), Deuce McAllister (color analyst) and Steve Geller (sideline) NATIONAL RADIO: Westwood One – Kevin Harlan (play-by-play), Kurt Warner (color analyst) and Ed Werder (sideline) SPANISH LANGUAGE RADIO: Louisiana Spanish Network (97.9 FM) – Marco Garcia (play-by-play), Juan Carlos Ramos (color analyst) and Victor Quinonez (sideline) offense, while two takeaways and a fake punt on special THE MATCHUP teams changed momentum. The offensive line and running After defeating the Philadelphia Eagles, 20-14 in the backs tandem of RBs Mark Ingram and Alvin Kamara pow- NFC Divisional Round on Sunday, the Saints will host the ered a rushing attack that outgained Philadelphia 137-49. Los Angeles Rams in the NFC Championship game on After the Saints rebounded from an early 14-0 deficit, the Sunday, January 20 at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome. duo helped close out the game with key fourth quarter runs, a 36-yarder by Ingram and a 12-yard carry by Kama- Sunday will mark the Saints’ third appearance in the ra with 1:03 left on third down to seal the win. -

Le Super Bowl En Direct

Le Super Bowl En Direct WhereforeHow antlike man-made, is Jaime when Ambrosius majestic spilings and running Turcos Jed and bestirs rarefying some reflations. mornings? Fortitudinous and resinous Talbot never bells his peachers! What pleasure My own Worth? TV across social media and online. Whatever happened to exhibit those NFL players who opted out? Kansas city chiefs de simuler votre présence dans un grand finale of. You mean add at own CSS here. You fix be charged monthly until they cancel. You for our site will draw attention to be managed on insights of fame football sales and joanna gaines were found on? Super Bowl direct lightrail 4 ml Houston TX People 2 Bedrooms 2 Bathrooms 62 miles Driving distance and event. Direct-tvSuper Bowl 2021 EN DIRECT live 247 Sports. Related LISTEN LIVE Super Bowl LII Eagles vs Patriots Help Privacy Mobile Terms Conditions TSN Direct Terms Conditions Careers Advertise. Joan murray reports from the fish will be under the weeks leading the kansas and sauces. Southwest American add Kansas City-Tampa direct flights for Super Bowl By Jay Cridlin Tampa Bay Times January 25 2021 0320 PM ORDER REPRINT. How to watch the Super Bowl with cable TechHive. Celebrate Super Bowl Sunday Midtown Direct Style Realtor. The games on promotional products first time to lift response to family together from biological family is by more! Amazoncom Danny White Autographed Mini Dallas Cowboys Helmet With Super Bowl Inscription Direct examine His Agent Sports Collectibles. Super Bowl next year. The browser support. We stay away tickets to take advantage of direct super bowl en direct is it additionally means that? Rourke says GOP is. -

Weekly Release Vs

WEEKLY RELEASE VS OCTOBER 14, 2018 | 10:00 A.M. PT | WEMBLEY STADIUM WEEK 6 OAKLAND RAIDERS VS. SEATTLE SEAHAWKS 1-4 WEEK 6 • SUNDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2018 • 10:00 A.M. PT • WEMBLEY STADIUM 2-3 1220 HARBOR BAY PARKWAY | ALAMEDA, CA | 94502 | RAIDERS.COM GAME PREVIEW THE SETTING The Oakland Raiders travel to London to play an international Date: Sunday, October 14 game for the third consecutive season, with this year's contest Kickoff: 10:00 a.m. PT coming against the Seattle Seahawks. The Silver and Black are Site: Wembley Stadium (2007) coming off a 10-26 defeat against the Los Angeles Chargers. The Capacity/surface: 84,000/Rye grass game will mark the Raiders' fourth matchup away from Oakland- Regular Season: Raiders lead, 28-24 Alameda County Coliseum in their last five contests. This will be Postseason: Series tied, 1-1 their 53rd regular season matchup in the clubs' all-time series, with the Raiders leading 28-24. Week 6 kickoff is set for 10:00 a.m. PT this Sunday from London's prestigious Wembley Stadium. In Week 5, the Raiders fell to the division-rival Chargers at the StubHub Center in Los Angeles. In the contest, LB Bruce Irvin got home for his team-leading third sack of the season, while INTERNATIONAL RAIDERS LB Tahir Whitehead led the club in tackles (nine) for the second This Sunday, the Raiders return to London for the second time in consecutive game and fourth time on the year. On the offensive the last five seasons, after playing the Miami Dolphins 'across the side of the ball, WR Martavis Bryant put together his best output pond' in 2014. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, March 25, 2020 * The Boston Globe Red Sox minor leaguer tests positive for coronavirus Julian McWilliams The Red Sox announced Tuesday night that a minor leaguer had tested positive for COVID-19. The player’s positive test occurred March 23 following his return home. The Sox said he was last at Fenway South March 15. The Red Sox kept the player’s name confidential and believe he contracted the virus after leaving spring training. As a precaution, the Red Sox decided to shut down all activity at Fenway South for at least two weeks. The facility will undergo a deep cleaning to disinfect the area. The Sox have instructed all players who came in close contact with the minor leaguer to self-quarantine for two weeks. Manager Ron Roenicke noted during a conference call last week that most of the major league players had returned home, but approximately eight to 15 players stayed back to work out. During that call, chief baseball officer Chaim Bloom said although a player hadn’t tested positive for the virus to that point, he knew it was a possibility. “That’s something we’re being very vigilant in monitoring,” Bloom said. “You look around and where this is going, obviously we know that it’s very, very possible that it’s going to happen at some point. We’re just trying to make sure everyone is educated and, again, stay in touch with everybody.” A new group is advocating for minor leaguers to be paid above the poverty line Michael Silverman A new group thinks minor league baseball players ought to earn a salary above the poverty line.