Free Solo, Or Climbing in Posthuman Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

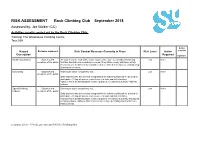

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018

RISK ASSESSMENT Rock Climbing Club September 2018 Assessed by: Joe Walker (CC) Activities usually carried out by the Rock Climbing Club: Training: The Warehouse Climbing Centre Tour: N/A Action Hazard Persons exposed Risk Control Measures Currently in Place Risk Level Action complete Description Required signature Bouldering (Indoor) Students and All students of the club will be made aware of the safe use of indoor bouldering Low None members of the public facilities and will be immediately removed if they fail to comply with these safety measures or a member of the committee believe that their actions are endangering themselves or others. Auto-Belay Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay climbing indoors. Speed Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Low None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate - Fitting a harness, correct use of a twist and lock carabiner, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to auto belay and speed climbing indoors, ability to differentiate between speed climbing and normal auto belay systems. y:\sports\2018 - 19\risk assessments\UGSU Climbing RA Top Rope Climbing Students and Warehouse basic competency test. Med None (Indoor) members of the public Only students who are deemed competent in the following skills will be allowed to participate in belaying - Fitting a harness, tying of a threaded figure of 8 knot, correct use of a belay device, correct belaying technique, competency in identifying faults in any equipment relevant to top rope climbing indoors. -

SHOOT Magazine March/April 2019 Issue

March/April 2019 March/April Chat Room 4 The Road To Emmy Preview Hot Locations 10 4 Spring 2019 DIR Adam McKay Lauren Greenfield Chat Room 18 ECT online.com Series SHOOT ORS Matthew Heineman 8 Ramaa Mosley www. Up-and-Coming Directors 19 Floyd Russ Ridley Scott Spike Jonze Cinematographers & Cameras 22 Top Ten VFX & Animation Chart 26 Top Ten Music Tracks Chart 28 TO GET CONNECTED THE FURTHEST REACHES OF YOUR IMAGINATION ARE CLOSER THAN YOU THINK. With versatile landscapes, experienced film crews and incentivized tax breaks, the only limit to filming in the U.S. Virgin Islands is your imagination. Enjoy up to a 29% tax rebate and up to a 17% transferable tax credit when you film in the USVI. For more opportunities in St.Croix, St. John and St. Thomas, call 340.774.8784 ext. 2243. filmusvi.com DOWNLOAD THE FILM USVI APP: © 2019 U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Tourism USVI19037_9x10.875_SHOOT.indd 1 3/22/19 4:09 PM AGENCY: JWT/Atlanta SPECS: 4C Page Bleed PUB: SHOOT Magazine CLIENT: USVI TRIM: 9” x 10.875” DATE: March/April, 2019 AD#: USVI19037 BLEED: 9.25” x 11.125” HEAD: “The Furthest Reaches of LIVE: 8.5” x 10.375” your Imagination...” Perspectives The Leading Publication For Film, TV & Commercial Production and Post March/April 2019 spot.com.mentary By Robert Goldrich Volume 60 • Number 2 www.SHOOTonline.com EDITORIAL Publisher & Editorial Director Serious Comedy Roberta Griefer 203.227.1699 ext. 701 [email protected] Editor Robert Goldrich Our Up-and-Coming known for its humorous chops, and hope- her feature film, Late Night. -

16Th Annual Tahoe Adventure Film Festival Launches December 8, 2018 at Mountbleu Resort, Lake Tahoe

16th Annual Tahoe Adventure Film Festival Launches December 8, 2018 at MountBleu Resort, Lake Tahoe South Lake Tahoe, California – Marking sixteen years of adventure sports cinematography and culture, Tahoe Adventure Film Festival (TAFF) is the annual gathering with the outdoor adventure community, animated with music, go-go dancers, wild entertainers, and dramatic action imagery. All before the films begin. It’s where the industry’s best filmmakers premier their latest adventure sports films one night only hosted by festival creator and adventurer, Todd Offenbacher. “We select the films, not judge them. Then our community comes together to honor what these film represent”. It’s tongue in cheek humor, combined with a celebration of our unique South Lake Tahoe lifestyle and culture,” says Offenbacher. TAFF inspires the adventure sports community with newly released films of daring exploits and epic adventures in some of the most remote places and harshest conditions that test the human spirit. Filmmakers capture the power and intensity of skiing, snowboarding, kayaking, rock climbing, surfing, mountain biking, BASE jumping and other heart pounding sports that feed our addiction to adventure. Some segments are special edits including previews of films that have not been released. The sixteenth annual coveted Golden Camalot award will be a surprise again this year. “We will reward a hero in our local community” says Offenbacher. We originally created the award to honor action and adventure sports pioneers for their astounding contributions, excellence, achievements, and leadership. “Just like the festival, the award’s scope continues to evolve.” Past recipients include Royal Robbins, Tommy Caldwell, Glen Plake, Fred Beckey, Jeremy Jones, Alex Honnold, Steve Wampler, Hatchett Brothers, Corey Rich, Doug Stoup, Robb Gaffney, Chris McNamerra, Chris Davenport, and Jamie Anderson. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Alex Honnold at the International Mountain Summit.Pdf

Pressebüro | Ufficio stampa | Press office IMS - International Mountain Summit Contact: Erica Kircheis | +39 347 6155011 | [email protected] Brennerstraße 28 | Via Brennero 28 | I-39042 Brixen/Bressanone [email protected] | www.ims.bz Alex Honnold, the first (and for now the only) to climb the big wall on El Capitan without rope will be gueststar at the International Mountain Summit in Bressanone/South Tyrol (Italy) A great step for Mountaineering has been made. After his incredible free solo climbing of 1,000 meters of El Capitan, Alex Honnold will participate in the IMS in Bressanone. Now ticket office is open. Alex Honnold started to climb as a child at the age of 11 . The passion for this sport grew with him so much that at 18 he interrupted his studies at Berkeley to dedicate himself exclusively to climbing. This was the beginning of his life as a professional climber. Honnold is known as much for his humble, self-effacing attitude as he is for the dizzyingly tall cliffs he has climbed without a rope to protect him if he falls. “I have the same hope of survival as everybody else. I just have more of an acceptance that I will die at some point”, extreme climber A lex Honnold said in an interview with National Geographic. Honnold is considered the best free solo climber in the world and holds several speed records, for instance for El Capitan in Yosemite National Park in California, which he climbed a few weeks ago in less than 4 hours without rope or any other protection. -

OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary Pursuits in the Outdoors Have Defined American Culture Since # Course Numbers with the # Symbol Included (E.G

University of New Hampshire 1 OUT 515 - History of Outdoor Pursuits in North America OUTDOOR EDUCATION (OUT) Credits: 4 Voluntary pursuits in the outdoors have defined American culture since # Course numbers with the # symbol included (e.g. #400) have not the early 17th century. Over the past 400 years, activities in outdoor been taught in the last 3 years. recreation an education have reflected Americans' spiritual aspirations, imperial ambitions, social concerns, and demographic changes. This OUT 407B - Introduction to Outdoor Education & Leadership - Three course will give students the opportunity to learn how Americans' Season Experiences experiences in the outdoors have influenced and been influenced by Credits: 2 major historical developments of the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th, and early An exploration of three-season adventure programs and career 21st centuries. This course is cross-listed with RMP 515. opportunities in the outdoor field. Students will be introduced to a variety Attributes: Historical Perspectives(Disc) of on-campus outdoor pursuits programming in spring, summer, and fall, Equivalent(s): KIN 515, RMP 515 including hiking, orienteering, climbing, and watersports. An emphasis on Grade Mode: Letter Grade experiential teaching and learning will help students understand essential OUT 539 - Artificial Climbing Wall Management elements in program planning, administration and risk management. You Credits: 2 will examine current trends in public participation in three-season outdoor The primary purpose of this course is an introduction -

Single Rope Technique (SRT)

tci mag 3_06_Backv2.qxp 02/27/2006 3:30 PM Page 60 Climbing Single Rope Technique (SRT) By Jeff Jepson he single rope technique (SRT) employs a static climbing line sys- T tem and is used as a means of canopy access only. The SRT is hard to beat when the climb is long or when the rope cannot be isolated around a single limb. This is often the case when installing lines in tall conifers or thickly crowned decidu- ous trees. Many of the same working and descending limitations that exist when footlocking on a doubled line apply to the SRT as well. The suggested equipment, procedures, and techniques presented on the following pages are but a few of many options avail- able for climbing a single line. For more information on SRT see the book On Rope, by Smith/Padgett. Climbing Line Anchoring Precautions There are concerns and potential hazards that exist when the climbing line is anchored to the base of the tree that do not occur when anchoring the line to the limb itself. Climbers need to be aware of the loading forces that occur on the branch or crotch that is redirecting the climbing line (see figure 1a) to an anchor point below (2a, 2b). This situation exposes the redi- Christina “Chrissy” Spence of Gisborne, New Zealand, won the title of Women's International Tree Climbing Champion at recting limb to twice the load that would the International Society of Arboriculture’s 29th International Tree Climbing Championship in Nashville in 2005. Spence occur if the rope was anchored to the climbed on Yale Cordage’s XTC line for the competition. -

Guidelines for a Quality Trail Experience

Guidelines for a Quality Trail Experience mountain bike trail guidelines January 2017 About BLM The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) may best be described as a small agency with a big mission: to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations. It administers more public land – over 245 million surface acres – than any other federal agency in the United States. Most of this land is located in the 12 Western states, including Alaska. The BLM also manages 700 million acres of subsurface mineral estate throughout the nation. The BLM’s multiple-use mission, set forth in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976, mandates that we manage public land resources for a variety of uses, such as energy development, livestock grazing, recreation, and timber harvesting, while protecting a wide array of natural, cultural, and historical resources, many of which are found in the BLM’s 27 million-acre National Landscape Conservation System. The conservation system includes 221 wilderness areas totaling 8.7 million acres, as well as 16 national monuments comprising 4.8 million acres. IMBA IMBA was founded in 1988 by a group of California mountain bike clubs concerned about the closure of trails to cyclists. These clubs believed that mountain biker education programs and innovative trail management solutions UJQWNF DG FGXGNQRGF CPF RTQOQVGF 9JKNG VJKU ƒTUV YCXG QH VJTGCVGPGF VTCKN access was concentrated in California, IMBA’s pioneers saw that crowded trails and trail user conflict were fast becoming worldwide recreation issues. This is why they chose “International Mountain Bicycling Association” as the organization’s name. -

Where to Go: Local Rock Climbing

Where to Go: Local Rock Climbing Want to try some outdoor climbing but don’t know where to go? Here are some local climbing spots that are within reasonable driving distance. Participants are reminded that climbing is inherently dangerous, and should only climb outside with proper training and equipment. For more information, ask any Adventure Assistant. Top Rope Sites Hidden Rocks‐ 30 minute drive time – 40 minute hike Great for beginners thru advanced climbers. Hidden Rocks has something for everyone. A gem of a training ground, perfect for the end‐of‐the day blitz to nail a few lines, the mid‐week escape to solitude and top‐roping, bouldering solitude, or just hiking in an incredible setting of forests, rock, and waterfalls. Route information: http://www.rockclimbing.com/routes/North_America/United_States/Virginia/North_Western/Hidden_Rocks/ Guide Book: Climbing Rockingham County by Lester Zook Directions: Take 42 south towards Dayton until you hit 257 West. Follow 257 for several miles. Road takes several sharp turns so follow signs closely. Take a right turn at the 257 Grocery Store, drive about a mile until you see a sign for Hone Quarry on your right. Enter Hone Quarry. Follow Yellow Blazed Trail behind parking lot. Follow trail, crossing stream several times. Watch for trail to turn right up hill. Follow uphill to rocks. Elizabeth Furnace‐ 60 minute drive time – 5 minute hike Well worth the drive for a good selection of sandstone climbs from 5.‐3‐5.11. top is easily accessed from a trail on the north ride of cliff. Follow 81 north to exit 296 Strasburg Turn right on VA‐55 toward Strasburg 1.5 miles. -

8 Must See Gear Items Remembering Dave Boyd

Showdown In The Land Of Fire by Nathan Ward Out Of The Office And Into The 2008 USARA National The Wild Championship 8 Must See Gear Items Plus • Czech Adventure Race Remembering Dave Boyd • Trinidad Coast to Coast • Taking a Bearing DecemberAdventure World Magazine 2008 is a GreenZine 1 Maybe you snowshoe. Explore the narrows. Or chance the rapids. However you define your love of the outdoors, we define ours by supporting grassroots conservation efforts to protect North America’s wildest places. Hunter Shotwell dedicated his life to Castleton Tower. Surely, you can dedicate an hour to yours. AdventureQMPPMSRTISTPI World Magazine December 20083RILSYVE[IIO1EOIMXLETTIR www.conservationalliance.com2 contents Features 14 Remembering Dave Boyd 18 Showdown in the Land of Fire by Nathan Ward 26 BG US Challenge Out of the Office and Into the Wild 29 Czech Adventure Race Departments 37 2008 USARA National 45 Training Championship Adventure Racing Navigation Part 5: Taking A Bearing Trinidad Coast to Coast 52 57 Gear Closet 4 Editor’s Note 5 Contributors 7 News From the Field 13 Race Director Profile Cover Photo: Patagonia Expedition Race 33 Athlete Profile Photo by Nathan Ward 34 Where Are They Now? This Page: Abu Dhabi Adventure Challenge 2008 63 It Happened To Me Photo by Monica Dalmasso editor’s note Adventure World magazine Editor-in-Chief Clay Abney Managing Editor Dave Poleto Contributing Writers Jacob Thompson • Kip Koelsch Jan Smolík • Nathan Ward Troy Farrar • Andrea Dahlke Mark Manning • Tom Smith Tim Holmstrom Contributing Photographers Will Ramos • Monica Dalmasso Nathan Ward • Tim Holmstrom James O’Connor • Jiri Struk Glennon Simmons Adventure World Magazine is dedicated to the preservation our natural resources Sunset on Tobago --- after the Trinidad Coast to Coast by producing a GreenZine. -

Canyoning Guiding Principles

ANU Mountaineering Club Canyoning Guiding Principles These Guiding Principles have been developed by experienced members of the ANU Mountaineering club, and have been approved by the ANU Mountaineering Club Executive. All ANU Mountaineering Club trip leaders will be expected to adhere to these principles. Departures from these principles will need to be approved by the Canyoning Officer. Activity Description What activities are involved: Canyoning involves scrambling, roped abseiling, walking, swimming and jumping. Canyoning can be conducted in dry canyons, wet canyons, on marked and unmarked trails. The types of skills needed: Canyoning skills include navigation, abseiling, building anchors, jumping, sliding and swimming. Areas that the ANUMC frequents: The ANUMC generally Canyon in the Blue Mountains, Bungonia National Park and the Namadgi National Park. Role of the Canyoning officer: The role of the Canyoning officer is to review trips according to the following set of safety standards. Trips will also be reviewed by the Trip Convenor. Trip leaders will be requested to ensure that trips follow these guidelines before being approved by the Activity Officer. Planning to submit a trip The following information should be consulted when planning to submit a trip: • Appropriate maps, guide books and websites including o OzUltimate.com o alternatezone.com o Canyons Near Sydney (several editions are available at the club gearstore) • Parks and road closures • Weather forecasts • Flood and storm warnings • Fire warnings • Local knowledge from leaders and other ANUMC members Trip description Trip descriptions will cover the following information: • Type and nature of the activity • Number of participants on trip – including number of beginner and intermediate participants • Skills, abilities and fitness required by participants. -

Columbia Filmcolumbia Is Grateful to the Following Sponsors for Their Generous Support

O C T O B E R 1 8 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 9 20 TH ANNIVERSARY FILM COLUMBIA FILMCOLUMBIA IS GRATEFUL TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT BENEFACTOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 20 TH PRODUCERS FILM COLUMBIA FESTIVAL SPONSORS MEDIA PARTNERS OCTOBER 18–27, 2019 | CHATHAM, NEW YORK Programs of the Crandell Theatre are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York filmcolumbia.org State Legislature. 5 VENUES AND SCHEDULE 9 CRANDELL THEATRE VENUES AND SCHEDULE 11 20th FILMCOLUMBIA CRANDELL THEATRE 48 Main Street, Chatham 13 THE FILMS á Friday, October 18 56 PERSONNEL 1:00pm ADAM (page 15) 56 DONORS 4:00pm THE ICE STORM (page 15) á Saturday, October 19 74 ORDER TICKETS 12:00 noon DRIVEWAYS (page 16) 2:30pm CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (page 17) á Sunday, October 20 11:00am QUEEN OF HEARTS: AUDREY FLACK (page 18) 1:00pm GIVE ME LIBERTY (page 18 3:30pm THE VAST OF NIGHT (page 19) 5:30pm ZOMBI CHILD (page 19) 7:30pm FRANKIE + DESIGN IN MIND: ON LOCATION WITH JAMES IVORY (short) (page 20) á Monday, October 21 11:30am THE TROUBLE WITH YOU (page 21) 1:30pm SYNONYMS (page 21) 4:00pm VARDA BY AGNÈS (page 22) 6:30pm SORRY WE MISSED YOU (page 22) 8:30pm PARASITE (page 23) á Tuesday, October 22 12:00 noon ICE ON FIRE (page 24) 2:00pm SOUTH MOUNTAIN (page 24) 4:00pm CUNNINGHAM (page 25) 6:00pm THE CHAMBERMAID (page 26) 8:15pm THE SONG OF NAMES (page 27) á Wednesday, October 23 11:30am SEW THE WINTER TO MY SKIN (page 28) 2:00pm MICKEY AND THE BEAR (page 28) 3:45pm CLEMENCY (page 29) 6:00pm