Integrating Visual Resource and Visitor Use Management Planning: a Case Study of the Moses H. Cone National Historic District, Blue Ridge Parkway Gary W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Ridge Parkway DIRECTORY & TRAVEL PLANNER Includes the Parkway Milepost

Blue Ridge Park way DIRECTORY & TRAVEL PLANNER Includes The Parkway Milepost Shenandoah National Park / Skyline Drive, Virginia Luray Caverns Luray, VA Exit at Skyline Drive Milepost 31.5 The Natural Bridge of Virginia Natural Bridge, VA Exit at Milepost 63.9 Grandfather Mountain Linville, NC Exit at Milepost 305.1 2011 COVER chosen.indd 3 1/25/11 1:09:28 PM The North The 62nd Edition Carolina Arboretum, OFFICIAL PUBLICATION BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY ASSOCIATION, INC. Asheville, NC. P. O. BOX 2136, ASHEVILLE, NC 28802 Exit at (828) 670-1924 Milepost 393 COPYRIGHT 2011 NO Portion OF THIS GUIDE OR ITS MAPS may BE REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA. Some Parkway photographs by William A. Bake, Mike Booher, Vickie Dameron and Jeff Greenberg © Blue Ridge Parkway Association Layout/Design: Imagewerks Productions: Fletcher, NC This free Travel Directory is published by the 500+ PROMOTING member Blue Ridge Parkway Association to help you more TOURISM FOR fully enjoy your Parkway area vacation. Our member- MORE THAN ship includes attractions, outdoor recreation, accom- modations, restaurants, 60 YEARS shops, and a variety of other services essential to the trav- eler. All our members are included in this Travel Directory. Distribution of the Directory does not imply endorsement by the National Park Service of the busi- nesses or commercial services listed. When you visit their place of business, please let them know you found them in the Blue Ridge Parkway Travel Directory. This will help us ensure the availability of another Directory for you the next time you visit the Parkway area. -

Moses H. Cone Memorial Park Developed Area Management Plan

MOSES H. CONE MEMORIAL PARK DEVELOPED AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN Environmental Assessment January 2015 i Cover Photograph Credit: Robert Clark ii iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK iv SUMMARY INTRODUCTION After Moses Cone’s death in 1908, his wife Bertha assumed ownership of the Moses Cone estate. To ensure the perpetual maintenance of the estate and its opening to the public after her death, Bertha Cone deeded the property to the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital in 1911, giving it the name “Moses H. Cone Memorial Park.” She retained the right to live at and manage the estate for the remainder of her life. Following Bertha Cone’s death in 1947, the trustees of the hospital agreed that the Blue Ridge Parkway (Parkway) would be better able to manage the estate. A deed filed for registration on January 11, 1950 transferred the Moses H. Cone Memorial Park from the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital to the United States of America. Under the terms of the indenture, the National Park Service assumed the obligations of the 1911 settlement and agreed to maintain a system of roads on the estate equal in extent to the system then in operation, and to develop the park in accordance with an agreed master plan, which has never been completed. This planning effort remedies that deficiency and creates a master plan for the Moses H. Cone Memorial park in compliance with the terms of indenture in the deed. By 1952 the NPS had developed a set of general development and master plan drawings to document where roads, parking areas and utilities were to be constructed. -

Flat Top Tower – Moses H. Cone Memorial Park, NC

Flat Top Tower – Moses H. Cone Memorial Park, NC Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 5.3 mls N/A N/A Hiking Time: Elev. Gain: 2 hours and 15 minutes with 30 minutes of break Parking: 584 ft Park at Flat Top Manor. 36.14928, -81.69288 By Trail Contributor: Zach Robbins Any hike at Moses H. Cone Memorial Park packs many views into relatively easy terrain and mileage for the Blue Ridge Mountains. Located just outside of Blowing Rock on the Blue Ridge Parkway, this estate was donated to the National Park Service in 1949 after the death of Bertha Cone. Prior to being controlled by the NPS, Moses Cone and his wife retired to this estate building over 20 miles of carriage trails, three lakes, and an observation tower on the highest point in the estate, Flat Top Mountain. Today the park is an excellent destination for hikers, horseback rides, and motorists. The carriage trails are all immaculately maintained and well-graded. None of the hikes in the park are difficult so it is perfect for the family and casual hikers. This hike starts at Flat Top Manor and winds through picturesque forest and fields for 2.6 miles to the observation tower on Flat Top Mountain. You will be treated to incredible views from a meadow near Cone Cemetery and 360° views from Flat Top Tower. Moses H. Cone Memorial Park is an outstanding introduction to the Blue Ridge Mountains for the family. Mile 0.0 – Hike begins at the parking lot for Flat Top Manor. -

Blue Ridge Parkway DIRECTORY TRAVEL PLANNER

63RD Edition Blue Ridge Park way www.blueridgeparkway.org DIRECTORY TRAVEL PLANNER Great Smoky Mountain Railroad Bryson City, NC Exit at Milepost 469.1 The Natural Bridge of Virginia Natural Bridge, VA Exit at Milepost 63.9 Includes THE PARKWAY MILEPOST Grandfather Mountain Linville, NC Exit at Milepost 305.1 Official Publication of the Blue Ridge Parkway Association 2012 COVER.indd 3 12/13/11 9:40:31 AM The North The 63rd Edition Carolina Arboretum, OFFICIAL PUBLICATION BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY ASSOCIATION, INC. Asheville, NC. P. O. BOX 2136, ASHEVILLE, NC 28802 Exit at (828) 670-1924 Milepost 393 COPYRIGHT 2012 NO Portion OF THIS GUIDE OR ITS MAPS may BE REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA. Some Parkway photographs by William A. Bake, Mike Booher, Vickie Dameron and Jeff Greenberg © Blue Ridge Parkway Association Layout/Design: Imagewerks Productions: Arden, NC This free Directory & Travel Plan- ner is published by the 500+ PROMOTING member Blue Ridge Parkway Association to help you more TOURISM FOR fully enjoy your Parkway area vacation. Our member- MORE THAN ship includes attractions, outdoor recreation, accom- modations, restaurants, shops, 60 YEARS and a variety of other services essential to the traveler. All our members are included in this For Blue Ridge Parkway information, including road Directory & Travel Planner. Distribution of the Directory & Travel Planner does not imply endorsement by the National conditions or closings, please visit www.nps.gov/blri Park Service of the businesses or commercial services listed. When you visit their place of business, please let them know www.blueridgeparkway.org you found them in the Blue Ridge Parkway Directory & Travel Planner. -

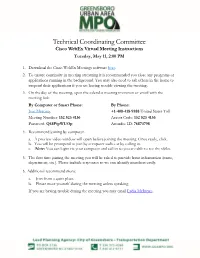

Technical Coordinating Committee Cisco Webex Virtual Meeting Instructions Tuesday, May 11, 2:00 PM

Technical Coordinating Committee Cisco WebEx Virtual Meeting Instructions Tuesday, May 11, 2:00 PM 1. Download the Cisco WebEx Meetings software here. 2. To ensure continuity in meeting streaming it is recommended you close any programs or applications running in the background. You may also need to ask others in the home to suspend their applications if you are having trouble viewing the meeting. 3. On the day of the meeting, open the calendar meeting invitation or email with the meeting link. By Computer or Smart Phone: By Phone: Join Meeting, +1-408-418-9388 United States Toll Meeting Number: 132 523 4136 Access Code: 132 523 4136 Password: Q68PipWUf3p Attendee ID: 76874798 4. Recommend joining by computer. a. A preview video window will open before joining the meeting. Once ready, click. b. You will be prompted to join by computer audio or by calling in. c. Note: You can login via your computer and call in so you are able to see the slides. 5. The first time joining the meeting you will be asked to provide basic information (name, department, etc.). Please include responses so we can identify members easily. 6. Additional recommendations: a. Join from a quiet place. b. Please mute yourself during the meeting unless speaking. If you are having trouble during the meeting you may email Lydia McIntyre. Technical Coordinating Committee Meeting Agenda Tuesday, May 11, 2:00 PM WebEx Online Virtual Meeting Action Items: 1. March 10, 2021 Meeting Minutes 2. MTIP Amendment: Statewide Transit Projects 3. MTIP Amendment & Modification: MPO Area Roadway Projects 4. -

Hugh Morton's Grandfather Mountain and the Creation of Wilderness

“MAKING THE MOUNTAIN PAY”: HUGH MORTON’S GRANDFATHER MOUNTAIN AND THE CREATION OF WILDERNESS A Thesis by CHRISTOPHER RYAN EKLUND Submitted to the Graduate School Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2011 Department of History “MAKING THE MOUNTAIN PAY”: HUGH MORTON’S GRANDFATHER MOUNTAIN AND THE CREATION OF WILDERNESS A Thesis by CHRISTOPHER RYAN EKLUND May 2011 APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Timothy H. Silver Chairperson, Thesis Committee ____________________________ Neva J. Specht Member, Thesis Committee ____________________________ Bruce E. Stewart Member, Thesis Committee ____________________________ Lucinda M. McCray Chairperson, Department of History ____________________________ Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Research and Graduate Studies Copyright by Christopher Ryan Eklund 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “MAKING THE MOUNTAIN PAY”: HUGH MORTON’S GRANDFATHER MOUNTAIN AND THE CREATION OF WILDERNESS (May 2011) Christopher Ryan Eklund, B.A. Appalachian State University M.A. Appalachian State University Chairperson: Timothy Silver Grandfather Mountain, located in western North Carolina, was a private tourist attraction throughout the twentieth century before it was sold to the state as a park in 2009. As one of the most prominent private tourist attractions in the South, Grandfather Mountain offers an opportunity to examine the evolution of the tourism industry and its relationship with the government. Hugh Morton, Grandfather Mountain’s owner, also used language invoking natural preservation, wilderness, and conservation to help sell the mountain to tourists. Over the course of his ownership, the mountain developed into a recognizable symbol for wilderness and natural beauty, and through association with these concepts the peak attained public recognition as a natural enclave. -

Camping, Wildlife

INCLUDES THE PARKWAY MILEPOST ALONG THE Blue Ridge Parkway PARKWAY DIRECTORY & TRAVEL PLANNER You’ll find opportunities for recreation, hiking, bicycling, picnicking, camping, wildlife Chimney Rock Park, NC viewing and much more. Exit at Milepost 384.7 There are 469 miles of spectacular scenery from the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and Tennessee Folk Art Center Asheville,NC Milepost 382 Parkway Craft Center Celebrating at the Moses Cone Manor Meilepost 294 INCLUDES THE PARKWAY MILEPOST The 61st Edition OFFICIAL PUBLICATION BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY ASSOCIATION, INC. P. O. BOX 2136, ASHEVILLE, NC 28802 (828) 670-1924 COPYRIGHT 2010 NO Portion OF THIS GUIDE OR ITS MAPS may BE REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA. This free Travel Directory is published by the 600+ mem- ber Blue Ridge Parkway Association to help you more fully enjoy your Parkway area vacation. Our membership includes attractions, outdoor recreation, accommodations, restaurants, shops, and a variety of other services essential to the trav- eler. All our members are included in this Travel Directory. Distribution of the Directory does not imply endorsement by the National Park Service of the businesses or commercial services listed. When you visit their place of business, please let them know you found them in the Blue Ridge Parkway Travel Directory. This will help us ensure the availability of another Directory for you the next time you visit the Parkway area. Visit the Blue Ridge Parkway Association’s website for even more informa- tion: www.blueridgeparkway.org For a detailed Parkway map, ask at the Parkway Visitor Centers for the official “strip map”. -

2017-2018 Blowing Rock Chamber of Commerce Visitor Information Guide & Members’ Directory

2017-2018 Blowing Rock Chamber of Commerce Visitor Information Guide & Members’ Directory Blowing Rock Chamber of Commerce PO Box 406 | 132 Park Avenue | Blowing Rock, NC 28605 828/295-7851 | www.BlowingRock.com | www.BlowingRockNCChamber.com 2017-2018 Calendar of Events For a complete list of events, visit our website at www.blowingrock.com. May August 6 Music on the Lawn, Inn at Raggged Gardens 1-6 Blowing Rock Charity Horse Show, starts and runs through October Tate Show Grounds 20 Art in the Park, Downtown 7 Monday Night Concert Series, Broyhill 21 Concert in the Park, Memorial Park Park Gazebo 25 Farmers Market Thursdays’ starts and runs 12 Art in the Park, Downtown through October 12 Shagging at the Rock, The Blowing Rock Attraction June 13 Concert in the Park, Memorial Park 2-4 Nature Photography Wknd., Grandfather Mtn. 19 Art Ball, BRAHM 8-11 Blowing Rock Charity Horse Show, 26-27 Railroad Heritage Weekend, Tweetsie Tate Show Grounds 10 Art in the Park, Downtown September 11 Concert in the Park, Memorial Park 9 Art in the Park, Downtown 24 Blood, Sweat & Gears, 100-mile Bike Race 10 Concert in the Park, Memorial Park 25 Singing on the Mountain, Grandfather Mtn. 16 The Blowing Rock Music Festival, The Blowing Rock Attraction July 29 Tweetsie Railroad Ghost Train begins 1-31 An Appalachian Summer Festival 1 Independence Day Parade and Activities, October Downtown 7 Art in the Park, Downtown 2 4th of July Park Dance, Memorial Park 9 Boone Heritage Festival, Horn in the West 4 Fireworks Extravaganza, Tweetsie 17 Valle Country Fair, Valle Crucis 6-9 Highland Games, Grandfather Mtn. -

Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation 2017-2018 Annual Report

Sharing the Journey Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation 2017-2018 Annual Report brpfoundation.org 1 Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation Leadership Board of Trustees Bob Clark Staff Clary Powell Pickering Pat Shore Clark Outreach Coordinator Alfred Adams, Chair Carolyn Ward, Ph.D. Heather Cotton Adam Roades Jack Betts, Vice Chair JoAnn Davis Chief Executive Officer Craig Lancaster, Treasurer Program Manager, Kids in Parks Dan Donahue Willa Mays Rebecca Reeve, Secretary Jaime Roscoe Harvey Durham Chief Development Officer Paul Bonesteel Rich Embrey Foundation & Corporate Peter Givens Joe Epley Brandon Altemose Relations Officer Billie Brandon Howell Program Assistant, Kids in Parks Broaddus Fitzpatrick Allison Royal Jim McDowell Brian Gulden Jordan Calaway Graphic Design & Outreach John Mitchell Chuck Higgins Donor Services Coordinator Coordinator, Kids in Parks Jim Newlin Sean Higgins Ashley Edwards Jason Urroz Jerry Starnes Michael Hobbs Finance Director Program Director, Kids in Parks Cynthia Tessien David Holt Brad Wilson Raymond Hornak Richard Emmett Program Director, Jennifer Zuckerman Olson Huff Blue Ridge Parkway Blue Ridge Music Center Cecil Jackson Foundation offices Board of Advisors George Kegley Mandy Gee 717 S. Marshall St., Suite 105B, Becky Anderson Bob Lassiter Annual Giving Officer Winston Salem, NC 27101 Jim Barber Phil Noblitt Marianne Kovatch Anne Barnes Bob Shepherd Associate Director, 322 Gashes Creek Road Lou Bissette Gary Stewart Blue Ridge Music Center Asheville, NC 28803 Philip Blumenthal Kent Tarbutton Rita Larkin Greg Brown Anne Whisnant (866) 308-2773 Communications Director Hobie Cawood Richard “Stick” Williams brpfoundation.org 2 brpfoundation.org Cover photo: Sam Knob Trail, milepost 420 The Spirit of Collaboration A Strong Community he Blue Ridge Parkway is many things to ach year brings diverse challenges and fresh many people. -

Historic Resource Study of Moses H Cone Estate On

Moses H. Cone Memorial Park [to be provided by NPS SERO] Blue Ridge Parkway [to be provided by NPS SERO] Blue Ridge Parkway BLRI 5140 The Moses H. Cone Memorial Park is a historic designed landscape extending over more than 3,500 acres north of Blowing Rock in Watauga County, North Carolina. The estate is dominated by the rolling terrain representative of the Blue Ridge Mountain physiographic province. The summits of two mountains fall within the property as well as low areas along several stream valleys. The remainder of the property is characterized by the unique mountain landscape prevalent in the North Carolina Blue Ridge, including steeply sloped areas and valleys as well as level terraces. It was this unique and beautiful landscape setting that inspired Moses Cone to begin buying tracts of land to form the core of his country estate from 1893–1899. After the deaths of Moses Cone in 1908 and his wife Bertha in 1947, the property was transferred to the United States of America. This was completed when the trustees of Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital reached an agreement with the government whereby it would assume ownership of Flat Top Estate (to be called Moses H. Cone Memorial Park), with the National Park Service managing and protecting the park. The actual transfer of the property took place in 1949. Construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway through the park began in 1955. The parkway splits the property along its east/west axis. The section of the parkway that extends through Moses H. Cone Memorial Park was completed in 1957.