Retail (Apparel) APRIL 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwest Corner of Lincoln Road and Meridian Avenue

800 Lincoln Road Southwest Corner of Lincoln Road and Meridian Avenue 28,496sf at the Most Visible Retail Corner in South Beach 28,496sf at the Most Visible Retail Corner in South Beach · Multi-level flagship opportunity with 250 feet of wraparound frontage and high ceilings · Prized position at the center of Lincoln Road · Tremendous rooftop food and beverage opportunity · Exposure to Collins Avenue hotels, the new Miami Beach Convention Center, and Miami Beach’s affluent residential and tourism population · Available Immediately: White Box spec delivered on Ground and Second Level** · Approval to build up to 9,865sf on Second Floor Location SW corner of Lincoln Road & Meridian Avenue Approximate Size Ground Floor** 12,990sf Second Floor** 5,826sf Third Floor 9,680sf Total 28,496sf Possession Q4 2017 Site Status Formerly ArtCenter/South Florida Neighboring Tenants American Eagle Outfitters, Apple, Athleta, Club Monaco, H&M, Intermix, John Varvatos, lululemon athletica, Nike, Sephora, Urban Outfitters, Victoria’s Secret, and Zara Ground Level & Second Floor 18,816sf Third Floor (Plus Dedicated Entrance) 777sf + 529sf + 9,680sf Lincoln Road 100' 0" Terrace 1,755sf 120 ' 3" Tenant 1 Tenant 2 12,990sf 7,925sf 5,826sf 26 ' 7" N Ground Level Tenant 2 Second Level Tenant 2 Third Level 777sf 529sf Ceiling Height 10' 9"–22' 6" Frontage 100' on Lincoln Road 120' 3" on Meridian Avenue 17th Street 17th 16th Street 16th Lincoln LaneSouth Lincoln Colony Theatre Nike Express Capital One Yard House Lacoste Apple John Varvatos 7 For All Mankind Intermix Club Monaco Athleta Mayors Jewelers Gap Michigan Avenue Lincoln LaneNorth Lincoln Bacaro Miami Groovy’s Pizza KIKO & Bar ArtCenter/ Diesel South Florida rfrspace.com rfr.com Red Zebra See Adore Tocaya Uno de 50 P All Saints Meat Market Marciano PINK aerie Victoria’s Secret Jefferson Avenue lululemon Sunglass Hut CB2 athletica jclaffey 2061 308 212 Jordan S. -

Fossil Group Comments on Armani Group Partnership Richardson, TX, December 15, 2020, (GLOBE NEWSWIRE)

Fossil Group Comments on Armani Group Partnership Richardson, TX, December 15, 2020, (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) - Fossil Group, Inc. (NASDAQ: FOSL) today issued the following statement regarding its continued partnership with the Armani Group. The two companies established a partnership in 1997, and under the current license agreements, Fossil Group designs and distributes products under the Emporio Armani, Armani Exchange, and Emporio Armani Swiss brands. “We are proud of our long-standing relationship with the Armani Group and our ability to drive innovation and strong growth for Emporio Armani, Emporio Armani Swiss, and Armani Exchange. We want to congratulate Giorgio Armani on the announcement of their collaboration with Parmigiani Fleurier under the Giorgio Armani brand,” said Fossil Group CEO Kosta Kartsotis. “The Giorgio Armani brand entering the exclusive luxury watch market will help to build brand equity, excitement, and energy for the entire watch industry.” “Armani Group has had a strong partnership with Fossil Group for more than twenty years,” said Giuseppe Marsocci, Deputy Managing Director of Armani. “Their ability to design products that reflect the spirit and style of Armani gives us great confidence in the future growth of our relationship.” About Fossil Group, Inc. We are a global design, marketing, distribution and innovation company specializing in lifestyle accessories. Under a diverse portfolio of owned and licensed brands, our offerings include fashion watches, jewelry, handbags, small leather goods and wearables. We are committed to delivering the best in design and innovation across our owned brands, Fossil, Michele, Misfit, Relic, Skagen and Zodiac, and licensed brands, Armani Exchange, BMW, Diesel, DKNY, Emporio Armani, kate spade new york, Michael Kors, PUMA and Tory Burch. -

Save on Rarely Discounted Brands

SUPPORTING OUR SOUTHERN COMMUN ITIES PRI VATE TICKETED EVENT* n SAT., NOV. 5 • 6- 1OAM PRE-SA LE DATES (1 - \ OCT. 25- NOV. 4 SAVE ON RARELY DISCOUNTED ,. BRANDS FREE PEOPLE , MICHAEL KOR S, FRYE, CALVIN KLE IN, KAREN KANE , VINCE CAMUTO , DOONEY & BOURKE , COACH, KATE SPADE NEW YORK & SO MANY MORE ! / SATURDAY,N OV.5, EARN on cosmetics storewid e & fragrance with your Belk purchases Rewards Card with your Belk Rewards Card •subject lo credit approval and excludes all gift cards, non-merchandise & leased departments. Cannot be combined with any other Rewards points otters. See store for details. • I I I I I I I I I I I I ,k · ~ r ..{• \ . .. -?·~ ... ' .. ' . : ~ ..' ... • ' I .. • • • • • ' •• •• -- • ------- -- - • • J WOMEN'S take an extra SHOES take an extra take an extra % ENTIRE ENTIRE ENTIRE STOCK' % % OFF STOCK OFF STOCK" REGULAR & SALE WOMEN'S OFF fron1 Anne �<lein, Calvin l(lein, REGULAR & SALE WOMEN'S REGULAR & SALE BETTER COATS Jones New York, London Fog3, Gallery, & MEN'S DESIGNER SHOES & SPORTSWEAR & SUITS for misses, Jessica Simpson, l<ensie, Guess & more BOOTS from Frye, Sam Edelman, petites & today's woman fron1 Kaari Cole Haan, l<ate Spade New York, BlueTM ' MICHAEL Michael Kors, Calvin TOTAL SAVINGS l!JP TO 60% "Excludes Kate Spade Vince Camuto, Free People, French Klein, Vince Camuto, Karen Kane, Sophie Connection, Johnston & Murphy Max, Lauren Ralph Lauren, Lucky Brand, take. an extra and more Calvin Klein Jeans, Vir1tage America Blues, TOTAL SAVIWGS UP TO 50% Chaus, Crown & lvyr"',Rafaella, Melissa Paige, Grace, -

Buyers - Suppliers - Initiatives

Buyers - Suppliers - Initiatives Bannari Amman Eastman Exports KPR Mill SSM India Buyers Sourcing from HQ country member of joint initiative Abercrombie & Fitch Bannari Amman US member of BSR Mills and Sundries Working Group American Eagle Outfitters Bannari Amman US FLA member American Sportswear Eastman Exports US Artis Eastman Exports Germany Baseco Eastman Exports Chile Bestseller Eastman Exports Denmark member ETI TN MSI Group Blue Star Imports Bannari Amman US Brave Kid Eastman Exports Italy C&A SSM India, Eastman Exports the Netherlands member ETI TN MSI Group CAC Anvers Logisport KPR Mill Belgium Catecu Eastman Exports Chile Choice Discount Store KPR Mill UK Color Image Apparel Eastman Exports US Cortefiel Eastman Exports Spain Crew 2000 Bannari Amman UK Crystal Martin SSM India, Eastman Exports UK Decathlon KPR Mill, Eastman Exports France Diadora Eastman Exports Italy Diesel Eastman Exports Italy E.Land World., Ltd. Eastman Exports Korea El Corte Ingles Eastman Exports Spain BSCI member Ernstings Family KPR Mill Germany BSCI member Express Eastman Exports US Falabella Eastman Exports Chile Fashion Box (Replay) Eastman Exports Greece French Connection Eastman Exports UK member ETI TN MSI Group/ member of BSR Mills Gap Eastman Exports US and Sundries Working Group Garcia Eastman Exports Netherlands Global Traders Network Eastman Exports Globus Eastman Exports Germany Gymboree Eastman Exports US Harmont & Blaine Bannari Amman Italy Iguasport (= Decathlon Brazil) KPR Mill, Eastman Exports Brazil Impala Loft 8 Bannari Amman Germany -

Halton Hills, Ontario, Canada

HALTON HILLS, ONTARIO, CANADA PROPERTY OVERVIEW 404 Richmond Hill 407 ® 10 TORONTO PREMIUM OUTLETS Markham Vaughan JOINT VENTURE WITH SMARTREIT® 404 HALTON HILLS, ONTARIO, CANADA 401 410 407 401 Brampton Halton Hills 401 Toronto MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS SELECT TENANTS 407 y tier Fw ld Car na Do Mac Toronto: 23 miles Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5TH, Armani, Banana Republic Factory Store, 407 Mississauga CANADA Brooks Brothers Factory Store, Burberry Factory Outlet, Coach, Cole 401 Oakville Haan Outlet, Diesel, DKNY Company Store, GUESS Factory Store, 407 RETAIL USA HUGO BOSS, J.Crew Factory, kate spade new york, Michael Kors Outlet, 403 Lake Ontario GLA (sq. ft.) 358,000 NikeFactoryStore, Polo Ralph Lauren, Ted Baker London, Tommy Hilfiger Burlington Expansion GLA (sq. ft.) 140,000 Company Store, Tory Burch, True Religion, Under Armour 403 Hamilton TOURISM / TRAFFIC OPENING DATES 405 St. Catharines 190 406 Toronto is the provincial capital of Ontario and the largest city in Canada. Niagara Opened August 2013 Falls Expansion Opening 2018 It is located in southern Ontario on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario. With over six million residents in the greater metropolitan area, it is the fifth most populous city in North America. Toronto is part of a densely RADIUS POPULATION TORONTO populated region in southern Ontario known as the Golden Horseshoe. PREMIUM OUTLETS 15 miles: 1,790,309 HALTON HILLS, 30 miles: 5,546,655 As Canada’s economic capital, Toronto is home to the Toronto Stock ONTARIO, CANADA 45 miles: 7,702,272 Exchange and is one of the top financial centers in the world. -

The State of Fashion 2019 the State of Fashion 2019 the State of Fashion

The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion 2 The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion 2019 Contents Executive Summary 10 Executive Summary Executive Industry Outlook 12 Global Economy 18—37 Trend 1: Caution Ahead 19 Executive Interview: Joann Cheng 22 Trend 2: Indian Ascent 24 Executive Interview: Darshan Mehta 28 Global Economy Trend 3: Trade 2.0 31 Global Value Chains in Apparel: The New China Effect 34 Consumer Shifts 38—69 Trend 4: End of Ownership 39 Executive Interview: Jennifer Hyman 42 Consumer Shifts Trend 5: Getting Woke 45 Executive Interview: Cédric Charbit 48 Trend 6: Now or Never 51 Executive Interview: Jeff Gennette 54 Digital Innovation Made Simple 58 Trend 7: Radical Transparency 60 Dealing with the Trust Deficit 62 Fashion System Fashion Fashion System 70—91 Trend 8: Self-Disrupt 71 The Explosion of Small 74 Trend 9: Digital Landgrab 77 Executive Interview: Nick Beighton 80 Trend 10: On Demand 83 Is Apparel Manufacturing Coming Home? 86 MGFI McKinsey Global Fashion Index 92—99 Glossary 100 End Notes and Detailed Infographics 102 The State of Fashion 2019 The State of Fashion Foreword The year ahead is one that will go down in history. Greater China will for the first time in centuries overtake the US as the world’s largest fashion market. It will be a year of awakening after the reckoning of 2018 — a time for looking at opportunities, not just challenges. In the US and in the luxury sector it will be a year of optimism; for Europe and for struggling segments such as the mid-market, optimism may be in short supply. -

DIESEL STUDY 27/8/10 10:44 Page 1

DIESEL STUDY 27/8/10 10:44 Page 1 www.thetimes100.co.uk Live, breathe and wear passion Curriculum Topics • Product • Promotion • Place • Price • People Introduction in his home town Molvena, Italy. Acting on impulse, he decided to use his passion to make the clothes he wanted to wear. Renzo Have you ever heard of passion in the marketing mix? How was drawn to the rebellious fabric of the 1960s and rock & roll: about people? Those two Ps never seem to figure alongside the denim. It inspired him to create jeans which would allow him and famous four which you, will of course, know by heart. This case others to express themselves in ways other clothing simply could study shows that having the depth of passion and the right people not. Proving popular, Renzo made more and more of his hand- are crucial missing links in binding the regular Ps together. crafted creations, selling them around Italy from the back of his little van. The still-young Renzo is the proud owner and CEO of Diesel builds its entire existence around the passion for what it Diesel along with that impressive list of figures. That impulse and does. With a founder who sees his work as an art and not a passion apparently paid off. science, the company has redefined how a brand sees and communicates with its customers since 1978. It is the Diesel story Product we will look at in this case study. Diesel sells nice jeans. Close, but no ‘A’. Actually, it’s not that Diesel is a global clothing and lifestyle brand. -

Orlando, Florida

ORLANDO, FLORIDA ORLANDO INTERNATIONAL PREMIUM OUTLETS® HIGHLIGHTS Orlando International Premium Outlets is located just three miles from Universal Orlando Resort and less than ten miles from Walt Disney World and Orlando International Airport. It is the largest outlet shopping center in Florida and one of top-performing outlet centers in the industry. Located in the International Drive resort area, the center is an iconic destination in the heart of Orlando’s booming hospitality industry. Several new hotels are being built in the International Drive area with plans to add commercial and retail development along the I-Drive corridor. The city of Orlando welcomes over 66 million visitors annually including out-of-state and international travelers from markets that include Europe, South America, and Asia. PROPERTY OVERVIEW ORLANDO INTERNATIONAL PREMIUM OUTLETS® ORLANDO, FL MAJOR METROPOLITAN AREAS SELECT TENANTS Conroy SR-435 Florida Orlando: 10 miles Neiman Marcus Last Call, Saks Fifth Avenue OFF 5TH, 7 For All Mankind, Universal John Orlando Exit 75A Daytona Beach: 65 miles adidas, American Eagle Outfitters, Banana Republic Factory Store, Coach, Resort Yo Turnpike Tampa: 80 miles Columbia Sportswear, Diesel, Disney Character Warehouse, DKNY ung Pkwy Company Store, Forever 21, GUESS, HUGO BOSS, J.Crew Factory, RETAIL kate spade new york, LACOSTE Outlet, Michael Kors Outlet, Nautica, I-4 . Nike Factory Store, The North Face, Polo Ralph Lauren Factory Store, Oakridge n GLA (sq. ft.) 774,000; 180 stores Salvatore Ferragamo, St. John, Ted Baker London, Tommy Hilfiger, Exit 75A Tory Burch (coming soon), Tourneau, True Religion, Tumi, UGG®, Kirkma Under Armour, U.S. Polo Assn., Victoria’s Secret OPENING DATES International Dr. -

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 the New Age of Fashion and Luxury Contents

Global Powers of Luxury Goods 2020 The new age of fashion and luxury Contents Foreword 3 Quick statistics 4 The new age of fashion and luxury 5 Top 10 highlights 17 Top 100 24 Geographic analysis 31 Product sector analysis 37 New entrants 42 Fastest 20 43 Study methodology and data sources 45 Endnotes 47 Contacts 50 Foreword Welcome to the seventh edition of Global Powers of Luxury Goods. At the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted many losses: human, social and economic. What we are now experiencing is an unprecedented moment of crisis in modern history. However, it is during uncertain times that companies often come up with new ideas, converting the crisis into an opportunity, and adopting a long-term vision of future challenges. This prolonged disruptive situation is creating profound changes in consumer behavior and how companies are responding to these changes—prompting a debate about the future of the fashion and luxury industry. There is a general feeling of rethinking luxury and driving it in new directions, considering which business models will be feasible and more relevant in the new normal. Tradition and responsiveness, two elements that have always characterized luxury companies, will both be required to face great challenges in the post-COVID environment. We see the pandemic acting as a divider between the old way of doing business and the new scenario that is taking shape, characterized by changing consumer behavior. Hence, in this report, we talk about a new age for fashion and luxury and will explore the main trends that will drive the industry in the coming months. -

Exhibitor Brochure

THE SOURCING EVENT OF THE SEASON JANUARY 12 – 14, 2021 NEW ERA. NEW CONCEPTS. Launching with new show names this Winter, Texworld & Apparel Sourcing New York City introduce 3 new ways to join The Sourcing Event of the Season: Traditional Exhibition, Pop-up Sourcing & Virtual Platform. SAFETY FIRST. SOURCING SECOND. Returning to the Javits Center in New York City, the event opens back under new safety precautions and standards. Policies and procedures will be implemented for protective measures including temperature checks, sanitation stations and daily disinfection of the venue for the safety of all guests. TRADITIONAL POP-UP VIRTUAL EXHIBITION SOURCING PLATFORM Be part of the real-life experience. Let us do the work for you. Just like being there. Meet face to face with over 4,000 buyers in Buyers do not have to miss the touch & The online platform will serve as an the heart of the fashion capital of the USA, feel aspect of fabric and apparel by simply alternative marketplace for global New York City. Take advantage of the well- sending your products. The Doneger Group, manufacturers to stay relevant in the industry. attended seminar series, Trend Showcase a NYC-based trend agency with over 50 years With guaranteed visitor recommendations, & the networking hub for the experience in key trends in lifestyle, fashion, exhibitors have the opportunity to sourcing community. color & fabrics, will curate an onsite continuously connect & network “showroom” linking your company’s products with US buyers. to your virtual platform profile. INCLUDES: -

Diesel Report

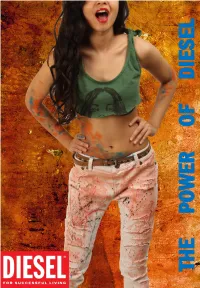

THE POWER OF DIESEL DIESEL AS A BRAND IN FRANCE R A S H I K A C H A N D R A CHAPTER I DIESEL : A MULTINATIONAL BRAND/ COMPANY DECLARATION I declare that this report and its contents are the original work. All references used in the report are given credit duly in the literature review and bibliography. This report and its contents are the property of the report writer and the same cannot be reproduced in any other manner without her due permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I take this opportunity to express my profound gratitude and deep regards to my mentors, Mr. Ankur Gulati, Mr. Anuj Lall and Ms. Vaishali Khurana for their exemplary guidance, mentoring and their constant encouragement throughout the course of this research. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCT -ION RENZO ROSSO HISTORY + ORIGIN CLOTHING PYRAMID DIESEL DIESEL ACQUISITION GREASY ROCKABILLY STORE QUIRKY URBAN BRAND ERA LOCATOR FASHIONISTA ANALYSIS CONSCIOUS DENIM HEDONISM FACTORY COMPETITI- AD DIESEL IN CAMPAIGNS VE ANALYSIS WORKED + FRANCE DIDN’T WORK GASTRONOMY CULTURAL COLLABORATIO -NS FRANCE EXCEPTIONS SOCIAL BEHAVIOUR RECOMMENDA BUSINESS -TIONS ETIQUETTES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Diesel was founded by the ‘Jeans Genius’, RENZO ROSSO, and Adriano Goldschmied in 1978, but when he wanted to take the company to a whole another level, he sold his shares of the Genius Group, and took the company and set out to enter into a new era. Diesel’s growth and development can be categorized into three separate eras: GREASY ROCKABILLY [1978-1993], QUIRKY URBAN FASHIONISTAS [1993-2000], and CONSCIOUS HEDONISM [2000- Present]. Their original motto “ONLY THE BRAVE” characterizes their first era. -

Inspection Copy Inspection Copy

INSEAD Diesel for Successful Living: Branding Strategies for an Up-market Line Extension in the Fashion Industry INSPECTIONNot For Reproduction COPY 09/2001-4948 This case was prepared by Vadim Grigorian (INSEAD MBA 2000) under the supervision of Pierre Chandon, Assistant Professor of Marketing at INSEAD, as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an asministrative situation. We thank Maurizio Marchiori and Antonella Viero from Diesel SpA for their valuable help and support. Copyright © 2001, INSEAD, Fontainebleau France. N.B. PLEASE NOTE THAT DETAILS OF ORDERING INSEAD CASES ARE FOUND ON THE BACK COVER. COPIES MAY NOT BE MADE WITHOUT PERMISSION. INSPECTIONNot For Reproduction COPY INSEAD 1 4948 It was the end of summer 1998. In less than a month, the first StyleLab fashion catwalk show would be held in London. Renzo Rosso needed to make tough decisions about the branding strategy of this new line and he needed to make them fast. StyleLab was the new upscale product line of Diesel SpA, the Italian casual wear company, famous for its cult Diesel jeans and controversial advertising. Diesel, one of the fastest- growing fashion companies of the 1990s, was number two in the jeans industry in Europe and had high expectations for StyleLab. StyleLab was designed to exploit growth opportunities in the emerging luxury segment of the casual wear market, competing with the likes of D&G (from Dolce & Gabbana) or Miu Miu (from Prada). StyleLab was also seen as a way to revitalize Diesel’s core brand, D-Diesel, which, as a fashion line, had to constantly reinvent itself to remain at the forefront of trends and styles.