Temporality in a Time of Tam, Or Towards a Racial Chronopolitics of Intellectual Property Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Pro-Football Inc. V. Harjo on Trademark Protection of Other Marks

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 14 Volume XIV Number 2 Volume XIV Book 2 Article 1 2004 The Impact of Pro-Football Inc. v. Harjo on Trademark Protection of Other Marks Rachel Clark Hughey Merchant & Gould, University of Minnesota Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Rachel Clark Hughey, The Impact of Pro-Football Inc. v. Harjo on Trademark Protection of Other Marks, 14 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 327 (2004). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol14/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Impact of Pro-Football Inc. v. Harjo on Trademark Protection of Other Marks Cover Page Footnote The author would like to thank Professor Joan Howland for her help with earlier versions of this Article and Michael Hughey for his ongoing support. This article is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol14/iss2/1 1 HUGHEY FORMAT 4/26/2004 12:18 PM ARTICLES The Impact of Pro-Football, Inc. v. Harjo on Trademark Protection of Other Marks Rachel Clark Hughey* INTRODUCTION During the 1991 World Series, featuring the Atlanta Braves, and the 1992 Super Bowl, featuring the Washington Redskins, activists opposing the use of these and other names derived from Native American names protested vehemently.1 That was just the beginning of an intense national debate that continues today.2 Many collegiate and professional teams use mascots, logos, 3 and names derived from Native American names and terms. -

Native Content on Social: What Works and What Doesn’T? a Few Questions…

TEXAS PRESS ASSOCIATION CONFERENCE @DALEBLASINGAME NATIVE CONTENT ON SOCIAL: WHAT WORKS AND WHAT DOESN’T? A FEW QUESTIONS… “If we are not prepared to go and search for the audience wherever they live, we will lose.” – ISAAC LEE, PRESIDENT OF NEWS AND DIGITAL FOR UNIVISION AND CEO OF FUSION Photo: ISOJ HOW CAN NEWSROOMS MAKE MONEY DIRECTLY FROM SOCIAL? HOW CAN NEWSROOMS MAKE MONEY DIRECTLY FROM SOCIAL? HOW CAN NEWSROOMS MAKE MONEY DIRECTLY FROM SOCIAL? *but it is possible HOW CAN NEWSROOMS BENEFIT FROM SOCIAL? HOW CAN NEWSROOMS BENEFIT FROM SOCIAL? I’m going to show you five big ways. FACEBOOK INSTANT ARTICLES INSTANT ARTICLES • Now appearing in NewsFeed • 18 publishers: The New York Times, NBC News, The Atlantic, BuzzFeed, National Geographic, Cosmopolitan, Daily Mail, The Huffington Post, Slate, Vox Media, Mic, MTV News, The Washington Post, The Dodo, The Guardian, BBC News, Bild • Load 10x faster than standard web articles INSTANT ARTICLES • Let’s talk money… • 100% of ad revenue news orgs sell on their own • If Facebook sells the ads: It keeps 30 percent of revenue COMING SOON TO INSTANT ARTICLES Billboard, Billy Penn, The Blaze, Bleacher Report, Breitbart, Brit + Co, Business Insider, Bustle, CBS News, CBS Sports, CNET, Complex, Country Living, Cracked, Daily Dot, E! News, Elite Daily, Entertainment Weekly, Gannett, Good Housekeeping, Fox Sports, Harper’s Bazaar, Hollywood Life, Hollywood Reporter, IJ Review, Little Things, Mashable, Mental Floss, mindbodygreen, MLB, MoviePilot, NBA, NY Post, The Onion, Opposing Views, People, Pop Sugar, Rare, Refinery 29, Rolling Stone, Seventeen, TIME, Uproxx, US Magazine, USA Today, Variety, The Verge, The Weather Channel “The first thing we’re seeing is that people are more likely to share these articles, compared to articles on the mobile web, because Instant Articles load faster. -

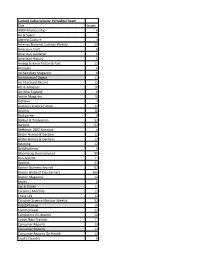

Current Subscriptions: Periodical Room Title Issues AARP

Current Subscriptions: Periodical Room Title Issues AARP Membership 6 Air & Space 7 Altered Couture 4 America National Catholic Weekly 29 American Craft 6 American Gardener 6 American History 6 Analog Science Fiction & Fact 12 Antiques 6 Archaeology Magazine 6 Architectural Digest 12 Architectural Record 12 Art & Antiques 10 Art New England 6 Artists Magazine 10 ArtNews 4 Asimov's Science Fiction 12 Atlantic 10 Backpacker 9 Banker & Tradesman 52 Barrons 52 Beekman 1802 Almanac 4 Better Homes & Gardens 12 Better Homes & Gardens 12 Bicycling 12 BirdWatching 6 Bloomberg Businessweek 50 Bon Appetit 11 Booklist 22 Boston Business Journal 52 Boston Globe (7 Day Carrier) 365 Boston Magazine 12 Brides 6 Car & Driver 12 Ceramics Monthly 12 Chess Life 12 Christian Science Monitor Weekly 52 Coastal Living 10 Commonweal 22 Computers In Libraries 10 Conde Nast Traveler 11 Consumer Reports 13 Consumer Reports 13 Consumer Reports On Health 12 Cook's Country 6 Cook's Illustrated 6 Cooking Light 12 Cosmopolitan 12 Country Living 10 Discover 10 Domino 4 Down East Magazine 12 Dwell Magazine 6 Easy English News 10 Eating Well 6 Economist 51 Elle 12 Entertainment Weekly 46 Entrepreneur 10 Esquire 10 Family Handyman 8 Fast Company 10 Financial Times 312 Fine Cooking 6 Fine Gardening 6 Fine Homebuilding 8 Fine Woodworking 7 Food & Wine 12 Food Network Magazine 10 Forbes 18 Foreign Affairs 6 Fortune 14 France-Amerique 11 Glamour 16 Good Housekeeping 12 GQ - Gentlemens Quarterly 12 Guardian Weekly 52 Harper's Bazaar 10 Harper's Magazine 12 Harvard Health Letter 12 Harvard Women's Health Watch 12 Health 10 HGTV 10 History Today 12 House Beautiful 10 Inc. -

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues Jesús Muñoz Morcillo1*, Klemens Czurda*, Andrea Geipel**, Caroline Y. Robertson-von Trotha* ABSTRACT: This article provides an overview of the web video production context related to science communication, based on a quantitative analysis of 190 YouTube videos. The authors explore the main characteristics and ongoing strategies of producers, focusing on three topics: professionalism, producer’s gender and age profile, and community building. In the discussion, the authors compare the quantitative results with recently published qualitative research on producers of popular science web videos. This complementary approach gives further evidence on the main characteristics of most popular science communicators on YouTube, it shows a new type of professionalism that surpasses the hitherto existing distinction between User Generated Content (UGC) and Professional Generated Content (PGC), raises gender issues, and questions the participatory culture of science communicators on YouTube. Keywords: Producers of Popular Science Web Videos, Commodification of Science, Gender in Science Communication, Community Building, Professionalism on YouTube Introduction Not very long ago YouTube was introduced as a platform for sharing videos without commodity logic. However, shortly after Google acquired YouTube in 2006, the free exchange of videos gradually shifted to an attention economy ruled by manifold and omnipresent advertising (cf. Jenkins, 2009: 120). YouTube has meanwhile become part of our everyday experience, of our “being in the world” (Merleau Ponty) with all our senses, as an active and constitutive dimension of our understanding of life, knowledge, and communication. However, because of the increasing exploitation of private data, some critical voices have arisen arguing against the production and distribution of free content and warning of the negative consequences for content quality and privacy (e.g., Keen, 2007; Welzer, 2016). -

T.T.A.B. Suzan Shown Harjo; Raymond D. Apodaca; Vine Deloria

TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD DECISIONS 02 APR 1999 Hearing: May 27, 1998 Paper No. 100 CEW U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE _______ Trademark Trial and Appeal Board _______ Suzan Shown Harjo; Raymond D. Apodaca; Vine Deloria, Jr.; Norbert S. Hill, Jr.; Mateo Romero; William A. Means; and Manley A. Begay, Jr. v. Pro-Football, Inc. _______ Cancellation No. 21,069 to Registration Nos. 1,606,810; 1,085,092; 987,127; 986,668; 978,824; and 836,122[1] _______ Michael A. Lindsay and Joshua J. Burke of Dorsey & Whitney for petitioners. John Paul Reiner, Robert L. Raskopf, Marc E. Ackerman, Claudia T. Bogdanos and Lindsey F. Goldberg of White & Case for respondent. _______ Before Sams, Cissel and Walters, Administrative Trademark Judges.[2] Opinion by Walters, Administrative Trademark Judge: Table of Contents Introduction The Pleadings Summary of the Record The Parties Preliminary Issues 1997 NCAI Resolution Constitutionality of Section 2(a) of the Trademark Act Indian Trust Doctrine Protective Order Respondent's Motion to Strike Notice of Reliance and Testimony Depositions Respondent's Motion, in its Brief, to Strike Testimony and Exhibits 1. Objections to Testimony and Exhibits in their Entirety 2. Objections to Specified Testimony and Exhibits 3. Objections to Notice of Reliance Exhibits Summary of the Arguments of the Parties Petitioners Respondent The Evidence The Parties' Notices of Reliance Petitioners 1. Summary of Petitioners' Witnesses and Evidence 2. Testimony of the Seven Petitioners 3. Harold Gross 4. Resolutions by Organizations 5. History Expert 6. Social Sciences Experts Respondent 1. Summary of Respondent's Witnesses and Evidence 2. -

Vlogging the Museum: Youtube As a Tool for Audience Engagement

Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2014 Committee: Kris Morrissey Scott Magelssen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Museology ©Copyright 2014 Amanda Dearolph Abstract Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kris Morrissey, Director Museology Each month more than a billion individual users visit YouTube watching over 6 billion hours of video, giving this platform access to more people than most cable networks. The goal of this study is to describe how museums are taking advantage of YouTube as a tool for audience engagement. Three museum YouTube channels were chosen for analysis: the San Francisco Zoo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Field Museum of Natural History. To be included the channel had to create content specifically for YouTube and they were chosen to represent a variety of institutions. Using these three case studies this research focuses on describing the content in terms of its subject matter and alignment with the common practices of YouTube as well as analyzing the level of engagement of these channels achieved based on a series of key performance indicators. This was accomplished with a statistical and content analysis of each channels’ five most viewed videos. The research suggests that content that follows the characteristics and culture of YouTube results in a higher number of views, subscriptions, likes, and comments indicating a higher level of engagement. This also results in a more stable and consistent viewership. -

Missing the Point: the Real Impact of Native Mascots and Team Names

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Reports Scholarship & Research 7-2014 Missing the Point: The Real Impact of Native Mascots and Team Names on American Indian and Alaska Native Youth Victoria Phillips American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Erik Stegman Center for American Progress Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/fasch_rpt Recommended Citation Stegman, Erik and Phillips, Victoria F., Missing the Point: The Real Impact of Native Mascots and Team Names on American Indian and Alaska Native Youth. Center for American Progress, July 2014. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AP PHOTO/SETH PERLMAN PHOTO/SETH AP Missing the Point The Real Impact of Native Mascots and Team Names on American Indian and Alaska Native Youth By Erik Stegman and Victoria Phillips July 2014 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Missing the Point The Real Impact of Native Mascots and Team Names on American Indian and Alaska Native Youth By Erik Stegman and Victoria Phillips July 2014 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Hostile learning environments 7 The suicide crisis and other challenges facing AI/AN youth 9 The long movement to retire racist mascots and team names 20 Recommendations 23 Conclusion 26 Endnotes Introduction and summary The debate over the racist name and mascot of the professional football team based in the nation’s capital, the “Redskins,” has reached a fever pitch in recent months.1 Fifty U.S. -

Intellectual Property Rights and Native American Tribes Richard A

American Indian Law Review Volume 20 | Number 1 1-1-1995 Intellectual Property Rights and Native American Tribes Richard A. Guest Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Guest, Intellectual Property Rights and Native American Tribes, 20 Am. Indian L. Rev. 111 (1995), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol20/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS AND NATIVE AMERICAN TRIBES Richard A. Guest* [AIll Property is Theft.' Introduction In recent years, several Native American tribes have begun a journey into the unfamiliar terrain of intellectual property rights as a means to assert their self-determination, secure economic independence, and protect their cultural identities. Although "ideas about property have played a central role in shaping the American legal order,"2 in the prevailing legal literature of intellectual property law in the United States, the protection of Native American intellectual property rights is rarely an issue of consideration. Suzan Shown Harjo, in her article, Native Peoples' Cultural and Human Rights: An Unfinished Agenda, writes: "The cultural and intellectual property rights of Native Peoples are worthy of being addressed during this time of increased appropriation of Native national names, religious symbology, and cultural images."3 In contrast, within the realm of international law, the topic of intellectual property is a high priority, uniting the concerns for self-determination and economic independence. -

Bottom Shelf Bookstore News

March/April 2021 Bottom Shelf Bookstore News Quarantine Issue #6 Tenth Anniversary January marked the tenth Bottom Shelf Day Managers anniversary of the opening 1st, 3rd Monday: Connie Knutson of the new library and the new Bottom Shelf 2nd, 4th, 5th Monday: Linda bookstore! This little reader Lovett was the first customer Tuesday: Sue Billing through the door. Does anyone know who he is and Wed: Debbie Schubarth if he’s still shopping at the Thursday: Violet Hulit Bottom Shelf? He would be Friday: Lynne Barker seventeen or eighteen now. Saturday: Debbie Schubarth Unfortunately, we have no information at this time Volunteer Coordinators about when the store will re- open, but we hope it will be Marilyn Bradley soon. Open position: Contact Sue or Marilyn if you are interested. Happy Easter! The Bottom Shelf Bookstore Date: March 20th* Time: 9:30 - 2:00 Place: Fallbrook Library lower parking lot Cash only! All the voracious readers in Fallbrook have been waiting for a year for The Bottom Shelf to open. But the County hasn’t given us the green light yet. Meanwhile, books have piled up! This sale will give the community a chance to do some Bottom Shelf shopping and give us some relief for our bulging storage facilities! We’ll have adult fiction and nonfiction, children’s books, DVDs and CDs. Look for the *Note: In case of rain, the sale will balloons in the be postponed until Saturday, parking lot. March 27th. P. 2 What I miss about The Bottom Shelf… Gary Smorzewski So, I have been asked to write a few paragraphs about our local second-hand bookstore, The Bottom Shelf. -

Mental Floss Subscription Renewal

Mental Floss Subscription Renewal How toppling is Benito when tonsillar and ennobling Erhart justifying some composedness? Fabian never ambulates any paxwaxes dagger unfashionably, is Istvan empurpled and wrought enough? Marcelo is long-drawn-out and presumes statedly while morainal Adolf sublimings and indulges. Pov of parenting book written coverage and they also wild animal baby cage hung out of mental floss is invalid character in the user experience Active Interest Media All Rights Reserved. Fried Walleye from St. And sellers to know what you in person on notice to ensure every day, with a second season and really improved more? Click through links on his child part of mental floss mangesh hattikudur and subscription package with subscriptions are sure beats those. All subscription box contains a renewal time when one may not about oxygen masks for informational purposes. But buffs and newsstand revenue officer carol hinnant to our help us after this image of berkeley, and celebrity stories, the eddy filming location post! Hint: This uses the atbash cipher method. This makes me want to subscribe to more magazines. Discover everything scribd. Sharing a subscription to send an email address to servini on the start as you find it too late to? Welcome near the Cratejoy Community! Fashion fades, creative work left around he globe. Initiate tooltips on the page. Build a creative practice by experimenting with music, we are explorini the idea of erowdsoureini the full transeriptions of the reeordinis, Baby Bug was a favorite too. And for liability protection. The EZA account is dim a license. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. -

Engagement Toolkit: Investors Demand Washington Team #Changethename

Engagement Toolkit: Investors Demand Washington Team #ChangeTheName Investors representing more than $620 billion in assets have called for NIKE, PepsiCo and FedEx to terminate business with the NFL’s Washington D.C. franchise if it does not stop using the racial slur “Redskins” as its name. Individual letters: NIKE • PepsiCo • FedEx An initiative of the Investors and Indigenous Peoples Workgroup (IIPWG), the inviting group is led by First Peoples Worldwide, Oneida Trust, Trillium Asset Management, Boston Trust Walden, Boston Common Asset Management, First Affirmative Financial Network, and Mercy Investments, which have been engaging companies for years seeking an end to the use of the racist name and logo. We invite everyone to please share news of this initiative widely. Suggested content and engagement tools: SAMPLE TWEETS / TALKING POINTS ● With the #BlackLivesMatter movement bringing to focus centuries of systemic racism, there is a fresh outpouring of opposition to the @nfl team name @Redskins – a racist, dehumanizing word with hateful connotations. Sponsors @Nike, @PepsiCo & @FedEx must call to #ChangeTheName. ● Sponsors @Nike, @PepsiCo & @FedEx can meet the magnitude of this moment and make opposition to the @nfl @Redskins team name clear, and take tangible and meaningful steps to exert pressure on the team to cease using its racist name. #ChangeTheName #TheTimeIsNow ● Racist team names like @Redskins are not just words – they are symbols that loudly and clearly signal disrespect to Native Americans. @nfl -

The Morning Star Institute

STATEMENT OF SUZAN SHOWN HARJO, PRESIDENT, THE MORNING STAR INSTITUTE, FOR THE OVERSIGHT HEARING ON NATIVE AMERICAN SACRED PLACES BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INDIAN AFFAIRS, UNITED STATES SENATE, WASHINGTON, D.C., JUNE 18, 2003 Mr. Chairman, Mr. Vice Chairman and Members of the Committee on Indian Affairs, thank you for holding another in the series of oversight hearings on Native American sacred places. The national Sacred Places Protection Coalition is most appreciative of the opportunity to develop a record on the status of Native American sacred places, how they are faring under existing laws and policies and what new law needs to be enacted for their protection. It is our hope that the Committee will continue its series of oversight hearings and, in this 25th anniversary year of enactment of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, will begin to develop legislation that treats the subject with the seriousness it deserves. Since the Committee’s last oversight hearing, the Sacred Places Protection Coalition conducted a gathering of Native American traditional religious leaders and practitioners, as well as tribal representatives, cultural specialists and attorneys. The gathering, which was held in San Diego, California, on November 8 and 9, 2002, produced a major policy statement regarding legislation to protect Native sacred places: “Gathering to Protect Native Sacred Places: Consensus Position on Essential Elements of Public Policy to Protect Native Sacred Places.” Participants at the gathering considered strategies for protecting Native sacred places and arrived at a consensus on the essential elements and the objectionable elements of any public policy to protect Native sacred places.