Some Horse Breeding Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horse Stud Farm in Dobrzyniewo

livestock breeding LIVESTOCK BREEDING The achieved genetic gain is determined by two factors – the genetic potential of animals and environmental conditions in which this potential may be realised. To obtain high productivity levels while ensuring good animal fertility and health, both of these factors have to be refined simultaneously. Genetic improvement is a long-term and costly process that requires a consistent approach to selection and matching. The nucleus herds supervised by the National Support Centre for Agriculture (Krajowy Ośrodek Wsparcia Rolnictwa – KOWR) represent a high genetic level, which, in order to be maintained, necessitates drawing on global genetic resources, including the use of Polish- and foreign-bred bulls for breeding. Apart from using the semen of prominent bulls, embryo transfer constitutes one of the most effective and relatively quick methods enabling genetic gain. The primary objective of embryo transfer is to produce bulls for insemination and heifers bred for improving their own herds. In 2017, a total of 1,272 embryos were obtained and 984 embryos were transferred. Transfer efficacy was 57%. A high animal genetic potential is displayed only in good environmental conditions, when a proper nutrition programme based on balanced feed intake is ensured. Our companies have built new livestock buildings or modernised the existing ones, using innovative and functional technical solutions applied in the global livestock building industry. In barns, cows can move around freely, enjoy easy access to feed and have uninterrupted air circulation. With a loose-housing system, it was possible to identify technological and feeding groups, depending on the milk yield and physiological status of cows, as well as to apply precise feed rations under the TMR feeding system. -

UNDERSTANDING HORSE BEHAVIOR Prepared By: Warren Gill, Professor Doyle G

4-H MEMBER GUIDE Agricultural Extension Service Institute of Agriculture HORSE PROJECT PB1654 UNIT 8 GRADE 12 UUNDERSTANDINGNDERSTANDING HHORSEORSE BBEHAVIOREHAVIOR 1 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Planning Your Project 3 The Basics of Horse Behavior 3 Types of Behavior 4 Horse Senses 4 Horse Communication 10 Domestication & Behavior 11 Mating Behavior 11 Behavior at Foaling Time 13 Feeding Behavior 15 Abnormal Behavior / Vices 18 Questions and Answers about Horses 19 References 19 Exercises 20 Glossary 23 SKILLS AND KNOWLEDGE TO BE ACQUIRED • Improved understanding of why horses behave like horses • Applying basic behavioral knowledge to improve training skills • Learning to prevent and correct behavioral problems • Better ways to manage horses through better understanding of horse motivation OBJECTIVES To help you: • Be more competent in horse-related skills and knowledge • Feel more confident around horses • Understand the applications of basic knowledge to practical problems REQUIREMENTS 1. Make a project plan 2. Complete this manual 3. Work on this project with others, including other 4-H members, 4-H leaders, your 4-H agent and other youth and adults who can assist you in your project. 4. Evaluate your accomplishments cover photo by2 Lindsay German UNDERSTANDING HORSE BEHAVIOR Prepared by: Warren Gill, Professor Doyle G. Meadows, Professor James B. Neel, Professor Animal Science Department The University of Tennessee INTRODUCTION he 4-H Horse Project offers 4-H’ers opportunities for growing and developing interest in horses. This manual should help expand your knowledge about horse behavior, which will help you better under T stand why a horse does what it does. The manual contains information about the basics of horse behavior, horse senses, domestication, mating behavior, ingestive (eating) behavior, foaling-time behavior and how horses learn. -

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby

HORSES, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2019) Kentucky Derby Winners, Alphabetically (1875-2019) HORSE YEAR HORSE YEAR Affirmed 1978 Kauai King 1966 Agile 1905 Kingman 1891 Alan-a-Dale 1902 Lawrin 1938 Always Dreaming 2017 Leonatus 1883 Alysheba 1987 Lieut. Gibson 1900 American Pharoah 2015 Lil E. Tee 1992 Animal Kingdom 2011 Lookout 1893 Apollo (g) 1882 Lord Murphy 1879 Aristides 1875 Lucky Debonair 1965 Assault 1946 Macbeth II (g) 1888 Azra 1892 Majestic Prince 1969 Baden-Baden 1877 Manuel 1899 Barbaro 2006 Meridian 1911 Behave Yourself 1921 Middleground 1950 Ben Ali 1886 Mine That Bird 2009 Ben Brush 1896 Monarchos 2001 Big Brown 2008 Montrose 1887 Black Gold 1924 Morvich 1922 Bold Forbes 1976 Needles 1956 Bold Venture 1936 Northern Dancer-CAN 1964 Brokers Tip 1933 Nyquist 2016 Bubbling Over 1926 Old Rosebud (g) 1914 Buchanan 1884 Omaha 1935 Burgoo King 1932 Omar Khayyam-GB 1917 California Chrome 2014 Orb 2013 Cannonade 1974 Paul Jones (g) 1920 Canonero II 1971 Pensive 1944 Carry Back 1961 Pink Star 1907 Cavalcade 1934 Plaudit 1898 Chant 1894 Pleasant Colony 1981 Charismatic 1999 Ponder 1949 Chateaugay 1963 Proud Clarion 1967 Citation 1948 Real Quiet 1998 Clyde Van Dusen (g) 1929 Regret (f) 1915 Count Fleet 1943 Reigh Count 1928 Count Turf 1951 Riley 1890 Country House 2019 Riva Ridge 1972 Dark Star 1953 Sea Hero 1993 Day Star 1878 Seattle Slew 1977 Decidedly 1962 Secretariat 1973 Determine 1954 Shut Out 1942 Donau 1910 Silver Charm 1997 Donerail 1913 Sir Barton 1919 Dust Commander 1970 Sir Huon 1906 Elwood 1904 Smarty Jones 2004 Exterminator -

The Evolution of Racehorse Clusters in the United States: Geographic Analysis and Implications for Sustainable Agricultural Development

sustainability Article The Evolution of Racehorse Clusters in the United States: Geographic Analysis and Implications for Sustainable Agricultural Development Paul D. Gottlieb 1,2, Jennifer R. Weinert 2, Elizabeth Dobis 3 and Karyn Malinowski 2,* 1 Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 55 Dudley Rd., New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA; [email protected] 2 Equine Science Center, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, ASB II 57 US HWY 1, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA; [email protected] 3 Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development, Pennsylvania State University, 207A Armsby Building, University Park, PA 16802, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-848-932-9419 Received: 31 October 2019; Accepted: 6 January 2020; Published: 8 January 2020 Abstract: Sustainability is frequently defined as the need to place equal emphasis on three societal goals: economic prosperity, environment, and social equity. This “triple bottom line” (TBL) framework is embraced by practitioners in both corporate and government settings. Within agriculture, the horse-racing industry and its breeding component are an interesting case study for the TBL approach to local development. The sector is to some extent a “knowledge industry”, agglomerating in relatively few regions worldwide. In the USA, choices made by breeders or owners are likely affected by sudden changes in specific state policies, especially those related to gambling. Both of these unusual conditions—for agriculture at least—have been playing out against a background of national decline in the number of registered racehorse breeding stock. This study traces changes, between 1995 and 2017, in the geographic distribution of registered Thoroughbred and Standardbred stallions. -

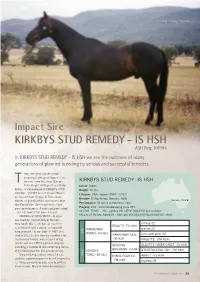

Kirkbys Stud Remedy

Article by Lindsay Ferguson Impact Sire KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH ASH Reg: 105194 In KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH we see the outcome of many generations of planned breeding by serious and successful breeders. hose breeders include people associated with great horses - Les KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH T Jensen, Theo Hill, John Stanton, Peter Knight, Alf Bignell and Phillip Colour: Brown Kirkby. In the pedigree of KIRKBYS STUD Height: 15.1hh REMEDY - IS HSH we see Impact Horses Lifespan:PROFILE: 24yrs approxJOHNSTONS (1987 - 2011) DARK SECRET - FS HSH as sire and dam, Impact or Foundation Breeder:Colour Phillip Kirkby, Narrabri,Brown NSW Horses as grandparents, and no less than Narrabri, NSW Performance: All round performance horse four Foundation Horses out of the eight Height 15.1 hh great-grandparents. A solid pedigree indeed Progeny:Lifespan 350 - most notable20 being years (1955mare –VET 1975) SCHOOL TONIC - HSH, gelding YALLATUP BACARDI and stallions – but let’s look at the horse himself. Breeder Unknown KIRKBYS STUD REMEDY - IS HSH YALLATUP REGAL REMEDY - HSH and BOONDEROO BLACKWOOD - HSH. Performance Lightly campdrafted was bred by Phillip Kirkby of Narrabri, New South Wales. He was an excellent 38 registered progeny, the mostdimray notable 02 being the mares CHEX,REALITY VICKIS FLIGHT - FS andHSH the stallion STARLIGHT STUD ANCHOR saddle horse with a docile, unflappable WARRENBRI glamor 02 temperament. He was born in 1987 and Progeny - HSH. Sire ROMEO - IS HSH died in 2011. In that time he travelled a lot, WARRENBRI JULIE lord coronation 02 made many friends, won a bunch of big + plus 3 generation pedigree- IM HSH to be included. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

Horse-Breeding – Being the General Principles of Heredity

<i-. ^u^' Oi -dj^^^ LIBRARYW^OF CONGRESS. Shelf.i.S.g^. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. HORSE-BREEDING BKING THE GENERAL PRINCIPLES OE HEREDITY APPLIED TO The Business oe Breeding Horses, IXSTEUCTIOJS'S FOR THE ^IaNAGE^HKNT Stallions, Brood Mares and Young' Foals, SELECTION OF BREEDING STOCK. r y-/' J. H. SANDERS, rdiinrof 'Tlie Bleeder's Gazette," '-Breeders' Trotting Stuil Book," '•ri'r<lu Honorary member of the Chicago Eclectic Medical SoeieU>'flfti'r.> ^' Illinois Veterinary Medical Association, ^rl^.^^Ci'^'' ~*^- CHICAGO: ' ^^ J. H. SANDERS & CO. ]8S5. r w) <^ Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1885, BY J. H. SANDERS, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. ^ la TABLE OF CONTENTS. Preface 5 CHAPTER I. General Principles of Breeding.—General Laws of Heredity- Causes of Variation from Original Typos — Modifications from Changed Conditions of Life—Accidental Variations or " Sports "— Extent of Hereditary Inflaence—The Formation of Breeds—In-Breeding and Crossing—Value of Pedigree- Relative Size of Sire and Dam—Influenee of First Impregna- tion—Effect of Imagination on Color of Progeny—Effect of Change of Climate on the Generative Organs—Controlling the Sex 9 CHAPTER II. Breeds of Horses.— Thoroughbreds — Trotters and Roadsters — Orloffs or Russian Trotters—Cleveland Bays—Shire or Cart Horses—Clydesdales—Percherons-Otber Breeds (58 CHAPTER III. Stallions, Brood Mares and Foals.— Selection of Breeding- Stock—General Management of the StaUion—Controlling the Stallion When in Use—When Mares Should be Tried—The -

Winter Newsletter 2012

Winter Newsletter 2012 Trakehners UK is the Marketing name of the Trakehner Breeders’ Fraternity. www.trakehners.uk.com 1 Winter 2012 Chairman’s Introduction and Report. New Treasurer’s Introduction to The Members Marketing Directors Report Registrar’s Report 2011 Foal List Members news Stud news - Home and Abroad Worming a Fresh Approach Freeze For The Future Spanish Horse News Update Bursary Winners Update Trakehners UK Merchandise Official Merchandise is available to buy – for full range please see the TBF web site where you will be able to buy your items online. www.trakehnerbreeders.com or Contact Nicky Nash: (Show Secretary) Again special thanks to Tanja Davis for her lovely photos, used in the 2012 Stallion Plan on the rear of this newsletter. 2 Chairman’s Report As we draw a close to 2011 we look back on another year with our beautiful Trakehner horses. It has been a financially challenging year for many people and we hope that 2012 will bring a more buoyant horse market. We have an exciting year ahead with the Trakehner Training Day on 10th March 2012 when Dieter Pothen and Paul Attew will be running a training day on preparing and showing your beautiful Trakehners to show off to their best in grading and showing classes. This training will include both a detailed presentation of conformational requirements followed by practical demonstrations of how to prepare your horse in the months before grading and how to show in hand and train for loose jumping. We do hope members will support this event. Booking forms available online at www.trakehners.uk.com Stallion owners, it is now time to join the Stallion Plan for 2012. -

Canadian Hanoverian Society Newsletter

CANADIAN HANOVERIAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Michael Boyd, Chairman, CHS George von Platen, President Hanoverian Breeders Club of Western Canada Vice President: Barbara Beckman (Manitoba) Secretary-Treasurer: Ms. Charlene Spengler (Alberta) Directors: John Dingle (British Columbia) Kathleen Sulz (Manitoba) Matthew von Platen (Alberta) Inga Hamilton, President Hanoverian Breeders Club of Eastern Canada Vice-President: Ruth Hanselpacker (Maritime region) Secretary/Treasurer: Ursula Hosking (Ontario West) Directors: Louise Masek (Ontario West) Greta Haupt (Ontario West) Marjorie Haus (Ontario West) Lynda Tetreault (Quebec) CHS Newsletter: Isabelle Schmid CHS Website: Jessica Lauzon December 5, 2017 In this Issue: Canadian Hanoverian Society Chairman’s Message by Michael Boyd Hanoverian Breeders Club of Eastern Canada President’s Message by Inga Hamilton Hanoverian Breeders Club of Western Canada President’s Message by George von Platen The Hanoverian has become a part of Canada: The 2017 Hanoverian Inspection Tour by Dr. Ludwig Christmann 2017 Inspection Tour Award Winners Information for ordering frozen semen from the Celle National State Stud News about Club Members Miscellaneous Canadian Hanoverian Society Chairman’s Message by Michael Boyd Well 2017 is quickly coming to an end and most of this year’s foals should be weaned by now and will have a couple of years to eat and grow before some serious training starts. Based on our inspection tour this year it looks like our breeders had a good year with quite a number of very good foals bred. Congratulations go out to the winners of this year’s Albert Kley Top Ten Foal awards and the Fritz Floto award for the top scoring dressage bred mare in this year’s Mare Performance Tests. -

The Horse Industry in Kansas

THE HORSE INDUSTRY IN KANSAS. OUTLINE. (1) The past history of the horse. (2) Improvement of the horse. (a) By breeding. (b) By feeding. (3) Change of type of horse from time to time for adaptation. to different needs. (a) Change in the mode of farming. (b) For pleasure driving and sporting. (4) Light and heavy horse breeding as an occupation. (a) Value of the conformation of light horses. (b) Value of style and action in light horses. (0) Value of weight. in draft horses. (d) Value of the conformation of draft horses. (5) Diminishing of the demand for cheap horses. (a) They are replaced by automobiles and electricity. (6) Folly of changing the line of breeding. (7) Methods for further improvement of the horse. (a) By better care and feed. (b) By better judgement in selection. (c) By breeding laws. (8) Conclusion. The horse stands at the head of a noble tribe of quadrupeds, which naturalists term solepedes, or single hoofed, from having but one apparent toe, covered by a single integument of horn, al- though beneath the skin on each side are nrotuberances which may be regarded as rudimental toes. According to the view of modern geologists there is but one genus of the tribe, namely, equus, which comprehends six species according to Proffessor Low, of Edinburgh. EQUUS ASINUS - The ass. EQUUS ZEBRA - The zebra. EQUUS QUAGGA - The quagga. EQUUS BURCHELLII - The striped quagga. EQUUS HEMIONUS - The dziggithai. EQUUS CABALLUS - The common horse. Nature has not formed this powerful creature to shun the control of man, but has linked him by his natural wants and in- stincts to our society.