Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Apostasy

The Great Apostasy R. J. M. I. By The Precious Blood of Jesus Christ; The Grace of the God of the Holy Catholic Church; The Mediation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Our Lady of Good Counsel and Crusher of Heretics; The Protection of Saint Joseph, Patriarch of the Holy Family and Patron of the Holy Catholic Church; The Guidance of the Good Saint Anne, Mother of Mary and Grandmother of God; The Intercession of the Archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael; The Intercession of All the Other Angels and Saints; and the Cooperation of Richard Joseph Michael Ibranyi To Jesus through Mary Júdica me, Deus, et discérne causam meam de gente non sancta: ab hómine iníquo, et dolóso érue me Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam 2 “I saw under the sun in the place of judgment wickedness, and in the place of justice iniquity.” (Ecclesiastes 3:16) “Woe to you, apostate children, saith the Lord, that you would take counsel, and not of me: and would begin a web, and not by my spirit, that you might add sin upon sin… Cry, cease not, lift up thy voice like a trumpet, and shew my people their wicked doings and the house of Jacob their sins… How is the faithful city, that was full of judgment, become a harlot?” (Isaias 30:1; 58:1; 1:21) “Therefore thus saith the Lord: Ask among the nations: Who hath heard such horrible things, as the virgin of Israel hath done to excess? My people have forgotten me, sacrificing in vain and stumbling in their way in ancient paths.” (Jeremias 18:13, 15) “And the word of the Lord came to me, saying: Son of man, say to her: Thou art a land that is unclean, and not rained upon in the day of wrath. -

Shakespeare on Screen a Century of Film and Television

A History of Shakespeare on Screen a century of film and television Kenneth S. Rothwell published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Kenneth S. Rothwell 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Reprinted 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Palatino A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Rothwell, Kenneth S. (Kenneth Sprague) A history of Shakespeare on screen: a century of film and television / Kenneth S. Rothwell. p. cm Includes bibliograhical references and index. isbn 0 521 59404 9 (hardback) 1. Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616 – Film and video adaptations. 2. English drama – Film and video adaptations. 3. Motion picture plays – Technique. I. Title. pr3093.r67 1999 791.43 6–dc21 98–50547 cip ISBN 0521 59404 9 hardback – contents – List of illustrations ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xiii List of abbreviations xiv 1 Shakespeare in silence: from stage to screen 1 2 Hollywood’s four seasons -

Mabel's Blunder

Mabel’s Blunder By Brent E. Walker Mabel Normand was the first major female comedy star in American motion pictures. She was also one of the first female directors in Hollywood, and one of the original principals in Mack Sennett’s pioneering Keystone Comedies. “Mabel’s Blunder” (1914), made two years after the formation of the Keystone Film Company, captures Normand’s talents both in front of and behind the camera. Born in Staten Island, New York in 1892, a teenage Normand modeled for “Gibson Girl” creator Charles Dana Gibson before entering motion pictures with Vitagraph in 1910. In the summer of 1911, she moved over to the Biograph company, where D.W. Griffith was making his mark as a pioneering film director. Griffith had already turned actresses such as Florence Lawrence and Mary Pickford into major dramatic stars. Normand, however, was not as- signed to the dramas made by Griffith. Instead, she went to work in Biograph’s comedy unit, directed by an actor-turned-director named Mack Sennett. Normand’s first major film “The Diving Girl” (1911) brought her notice with nickelodeon audiences. A 1914 portrait of Mabel Normand looking Mabel quickly differentiated herself from the other uncharacteristically somber. Courtesy Library of Congress Biograph actresses of the period by her willingness Prints & Photographs Online Collection. to engage in slapstick antics and take pratfalls in the name of comedy. She also began a personal ro- to assign directorial control to each of his stars on mantic relationship with Mack Sennett that would their comedies, including Normand. Mabel directed have its ups and downs, and would eventually in- a number of her own films through the early months spire a Broadway musical titled “Mack and Mabel.” of 1914. -

Sennett Creative Campus: Echo Park Modern/Creative Office Spaces 2219 Aaron Street (Corner of Aaron & Glendale), Echo Park, Ca 90026

(RENDERING) SENNETT CREATIVE CAMPUS: ECHO PARK MODERN/CREATIVE OFFICE SPACES 2219 AARON STREET (CORNER OF AARON & GLENDALE), ECHO PARK, CA 90026 David Aschkenasy Ryan Schimel David Ickovics Executive Vice President Director Principal Phone 310.272.7381 Phone 310.272.7384 Phone 310.272.7380 email [email protected] email [email protected] email [email protected] (RENDERING) The Sennett Creative Campus is greater Los Angeles’ most unique creative office destination. Spaces: A (1st Floor) The Campus offers one of the largest and architecturally significant, contiguous office spaces B (2nd Floor) available. Originally built in 1946, and fully modernized and renovated in 2013, with a new addition Size: +/- 1,800 sq ft each in spaces: 1745-1759 N Glendale Blvd is a 25,000 SF +/- campus environment that brings the Rate: $3.75 psf, Modified Gross glory of old Hollywood to life in the 21st Century. Comprised of 4 buildings, outdoor patios Available: March 1, 2018 and surface parking lots, 1745-1759 N Glendale Blvd is equipped with dramatic exposed high Features: • Brand New Construction ceilings, new HVAC & electric, polished concrete and floors, brand new restrooms, kitchens, • Two Available Spaces multiple skylights and ample parking. Greater Los Angeles is very limited with regard to true • Beautifully Built Out Creative Office with Open creative office space of this scale and caliber. While there is availability in Silicon Beach (Venice Kitchen and Large Restroom and Santa Monica), Hollywood, and the Arts District, the Sennett Creative Campus offers the • Join Moda Yoga (http://los-angeles.modoyoga. same Creative Office Build outs at a fraction of the price. -

Introduction

NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust (New York: Bantam, 1959), 131. 2. West, Locust, 130. 3. For recent scholarship on fandom, see Henry Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (New York: Routledge, 1992); John Fiske, Understanding Popular Culture (New York: Routledge, 1995); Jackie Stacey, Star Gazing (New York: Routledge, 1994); Janice Radway, Reading the Romance (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1991); Joshua Gam- son, Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America (Berkeley: Univer- sity of California Press, 1994); Georganne Scheiner, “The Deanna Durbin Devotees,” in Generations of Youth, ed. Joe Austin and Michael Nevin Willard (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Lisa Lewis, ed. The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (New York: Routledge, 1993); Cheryl Harris and Alison Alexander, eds., Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture, Identity (Creekskill, N.J.: Hampton Press, 1998). 4. According to historian Daniel Boorstin, we demand the mass media’s simulated realities because they fulfill our insatiable desire for glamour and excitement. To cultural commentator Richard Schickel, they create an “illusion of intimacy,” a sense of security and connection in a society of strangers. Ian Mitroff and Warren Bennis have gone as far as to claim that Americans are living in a self-induced state of unreality. “We are now so close to creating electronic images of any existing or imaginary person, place, or thing . so that a viewer cannot tell whether ...theimagesare real or not,” they wrote in 1989. At the root of this passion for images, they claim, is a desire for stability and control: “If men cannot control the realities with which they are faced, then they will invent unrealities over which they can maintain control.” In other words, according to these authors, we seek and create aural and visual illusions—television, movies, recorded music, computers—because they compensate for the inadequacies of contemporary society. -

New Findings and Perspectives Edited by Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett, Lucia Tralli Researching Women in Silent Cinema New Findings and Perspectives

in Silent Cinema New Findings and Perspectives edited by Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett, lucia Tralli RESEARCHING WOMEN IN SILENT CINEMA NEW FINDINGS AND PERSPECTIVES Edited by: Monica Dall’Asta Victoria Duckett Lucia Tralli Women and Screen Cultures Series editors: Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett ISSN 2283-6462 Women and Screen Cultures is a series of experimental digital books aimed to promote research and knowledge on the contribution of women to the cultural history of screen media. Published by the Department of the Arts at the University of Bologna, it is issued under the conditions of both open publishing and blind peer review. It will host collections, monographs, translations of open source archive materials, illustrated volumes, transcripts of conferences, and more. Proposals are welcomed for both disciplinary and multi-disciplinary contributions in the fields of film history and theory, television and media studies, visual studies, photography and new media. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ # 1 Researching Women in Silent Cinema: New Findings and Perspectives Edited by: Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett, Lucia Tralli ISBN 9788898010103 2013. Published by the Department of Arts, University of Bologna in association with the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne and Women and Film History International Graphic design: Lucia Tralli Researching Women in Silent Cinema: New Findings and Perspectives Peer Review Statement This publication has been edited through a blind peer review process. Papers from the Sixth Women and the Silent Screen Conference (University of Bologna, 2010), a biennial event sponsored by Women and Film History International, were read by the editors and then submitted to at least one anonymous reviewer. -

He Museum of Modern Art 1 West 53Rd Street, New York Telephone: Circle 5-8900 for Immediate Release

401109 - 68 HE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 1 WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART OPENS LARGE EXHIBITION OF WORK OF D. W. GRIFFITH, FILM MASTER It is difficult to blueprint genius, but in its exhibition documenting the life and work of David Wark Griffith the Museum cf Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, will attempt to show the progressive steps through which this American film pioneer between 1909 and 1919 brought to the motion picture the greatest contribution made by any. single individual. In that important decade he taught the movies to become an original and powerful instrument of expression in their own right. The Griffith exhibition.will open to xhe public Wednesday, November 13, simultaneously with an exhibition of the work of another American, the two combined under the title Two Great Ameri cans : Frank Lloyd Wright, American Architect and D. W. Griffith, American Film Master. Although at first glance there may seem to be no connection between them, actually a curious parallel exists. America's greatest film director and America's greatest architect, the one in the second decade of this century, the other roughly from 1905 to 1914, had an immense influence on European motion pictures and architecture. After the first World War this influ ence was felt in the country of its origin in the guise of new European trends, even though European architects and motion picture directors openly acknowledged their debt to Wright and Griffith. The Griffith exhibition was assembled by Iris Barry, Curator of the Museum's Film Library, and installed by her and Allen Porter, Cir culation Director. -

THTR 474 Intro to Standup Comedy Spring 2021—Fridays (63172)—10Am to 12:50Pm Location: ONLINE Units: 2

THTR 474 Intro to Standup Comedy Spring 2021—Fridays (63172)—10am to 12:50pm Location: ONLINE Units: 2 Instructor: Judith Shelton OfficE: Online via Zoom OfficE Hours: By appointment, Wednesdays - Fridays only Contact Info: You may contact me Tuesday - Friday, 9am-5pm Slack preferred or email [email protected] I teach all day Friday and will not respond until Tuesday On Fridays, in an emergency only, text 626.390.3678 Course Description and Overview This course will offer a specific look at the art of Standup Comedy and serve as a laboratory for creating original standup material: jokes, bits, chunks, sets, while discovering your truth and your voice. Students will practice bringing themselves to the stage with complete abandon and unashamed commitment to their own, unique sense of humor. We will explore the “rules” that facilitate a healthy standup dynamic and delight in the human connection through comedy. Students will draw on anything and everything to prepare and perform a three to four minute set in front of a worldwide Zoom audience. Learning Objectives By the end of this course, students will be able to: • Implement the comic’s tools: notebook, mic, stand, “the light”, and recording device • List the elements of a joke and numerous joke styles • Execute the stages of standup: write, “get up”, record, evaluate, re-write, get back up • Identify style, structure, point of view, and persona in the work we admire • Demonstrate their own point of view and comedy persona (or character) • Differentiate audience feedback (including heckling) -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

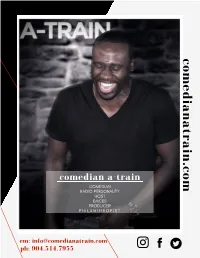

Comedian A-Train M COMEDIAN RADIO PERSONALITY HOST EMCEE PRODUCER P H I L a N T H R O P I S T

c o m e d i a n a t r a i n . c o comedian a-train m COMEDIAN RADIO PERSONALITY HOST EMCEE PRODUCER P H I L A N T H R O P I S T em: [email protected] ph: 904.514.7955 COMEDIAN A-TRAIN as seen and heard on bio Comedian A-Train, seen on WEtv’s Braxton Family Values, The Low Down with James Yon, River City Live, First Coast Living, and The Chat, is host of Yo Daddy’ Nem Podcast—iHeart Radio’s #1 Podcast in Duval, former co-host of Jacksonville’s #1 morning show, on 107.9 and Jacksonville’s #1 drive-time radio show on 103.7. He's a clean, traveling, stand-up, and corporate comedian, host and emcee. He tours with Original King of Comedy D. L. Hughley, and has toured with Kountry Wayne. He has featured for the biggest names in clean comedy, Michael Jr., viral sensation KevonStage, Dave Coulier (Uncle Joey on Full House), and Preacher Lawson (AGT). He's performed with Pete Lee (Jimmy Fallon and VH1’s Best Week Ever), Comedienne Dominique (Last Comic Standing), Bill Bellamy (Who's Got Jokes and Ladies Night Out), Ali Siddiq (Bring the Funny and Comedy Central), Loni Love (The Real), Deon Cole (Blackish and Grownish), Ronnie Jordan (Bossip), Huggy Low Down and Chris Paul (Tom Joyner Morning Show), and many others. Comedian A-Train has hosted the Zora Neal Hurston Festival, Orlando Jazz Festival, Steel City Jazz Festival— Birmingham, and Jacksonville Jazz Festival—the second largest in the country where he’s the first and only comedian to host in the city’s 40-year history. -

Hooray for Hollywood!

Hooray for Hollywood! The Silent Screen & Early “Talkies” Created for free use in the public domain American Philatelic Society ©2011 • www.stamps.org Financial support for the development of these album pages provided by Mystic Stamp Company America’s Leading Stamp Dealer and proud of its support of the American Philatelic Society www.MysticStamp.com, 800-433-7811 PartHooray I: The Silent forScreen andHollywood! Early “Talkies” How It All Began — Movie Technology & Innovation Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) Pioneers of Communication • Scott 3061; see also Scott 231 • Landing of Columbus from the Columbian Exposition issue A pioneer in motion studies, Muybridge exhibited moving picture sequences of animals and athletes taken with his “Zoopraxiscope” to a paying audience in the Zoopraxographical Hall at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Although these brief (a few seconds each) moving picture views titled “The Science of Animal Locomotion” did not generate the profit Muybridge expected, the Hall can be considered the first “movie theater.” Thomas Alva Edison William Dickson Motion Pictures, (1847–1947) (1860–1935) 50th Anniversary Thomas A. Edison Pioneers of Communication Scott 926 Birth Centenary • Scott 945 Scott 3064 The first motion picture to be copyrighted Edison wrote in 1888, “I am experimenting Hired as Thomas Edison’s assistant in in the United States was Edison upon an instrument which does for the 1883, Dickson was the primary developer Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (also eye what the phonograph does for the of the Kintograph camera and Kinetoscope known as Fred Ott’s Sneeze). Made January ear.” In April 1894 the first Kinetoscope viewer. The first prototype, using flexible 9, 1894, the 5-second, 48-frame film shows Parlour opened in New York City with film, was demonstrated at the lab to Fred Ott (one of Edison’s assistants) taking short features such as The Execution of visitors from the National Federation of a pinch of snuff and sneezing. -

Moma More Cruel and Unusual Comedy Social Commentary in The

MoMA Presents: More Cruel and Unusual Comedy: Social Commentary in the American Slapstick Film Part 2 October 6-14, 2010 Silent-era slapstick highlighted social, cultural, and aesthetic themes that continue to be central concerns around the world today; issues of race, gender, propriety, and economics have traditionally been among the most vital sources for rude comedy. Drawing on the Museum’s holdings of silent comedy, acquired largely in the 1970s and 1980s by former curator Eileen Bowser, Cruel and Unusual Comedy presents an otherwise little-seen body of work to contemporary audiences from an engaging perspective. The series, which first appeared in May 2009, continues with films that take aim at issues of sexual identity, substance abuse, health care, homelessness and economic disparity, and Surrealism. On October 8 at 8PM, Ms Bowser will address the connection between silent comedy and the international film archive movement, when she introduces a program of shorts that take physical comedy to extremes of dream-like invention and destruction. Audiences today will find the vulgar zest and anarchic spirit of silent slapstick has much in common with contemporary entertainment such as Cartoon Network's Adult Swim, MTV's Jackass and the current Jackass 3-D feature. A majority of the films in the series are archival rarities, often the only known surviving version, and feature lesser- remembered performers on the order of Al St. John, Lloyd Hamilton, Fay Tincher, Hank Mann, Lupino Lane, and even one, Diana Serra Cary (a.k.a. Baby Peggy), who, at 91, is the oldest living silent film star still active.