Trade Marks Inter Partes Decision O/293/19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

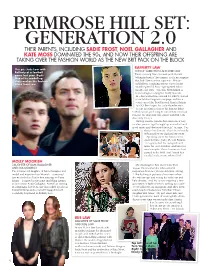

Primrose Hill Set: Generation

PRIMROSE HILL SET: GENERATION 2.0 THEIR PARENTS, INCLUDING SADIE FROST, NOEL GALLAGHER AND KATE MOSS DOMINATED THE 90s, AND NOW THEIR OFFSPRING ARE TAKING OVER THE FASHION WORLD AS THE NEW BRIT PACK ON THE BLOCK RAFFERTY LAW This pic: Jude Law with SON OF SADIE FROST AND JUDE LAW Rafferty at a football game last year. Right: Those piercing blue eyes and perfect pout One of his modelling belong in front of the camera, so it’s no surprise shots and on the Fashion that Jude Law’s carbon copy son, 19-year- Week front row old Rafferty is making serious waves in the modelling world. Since signing with Select models, the teen – who has been linked to Liam Gallagher’s daughter Molly Moorish, 18 – has walked the catwalk for DKNY, starred in an Adidas Originals campaign and been voted one of the Best Dressed Men in Britain by GQ. But despite his early showbiz start, he has no plans to follow his famous father to Hollywood, preferring to concentrate on music instead. He sings and play guitar with Brit rock duo Dirty Harry’s. “Having creative parents has made me a very creative person. I got brought up around art and goodg music and obviously fi lm sets,” he says, “I’ve always loved music. That’s been heavily infl uenced by my dad and my mum.” Speaking about his famous son’s quest for fame, Jude, 43, told Esquire, “He’s got to fi nd his own path and make his own mistakes, and have his own triumphs. -

“I'll Speak My Mind

“I’ll speak my mind - even if it hurts my career” Actor Chloë Grace Moretz talks about dating Brooklyn Beckham, taking on the Kardashians and standing up against sexism in Hollywood Interview by TIFFANY BAKKER s women in “It feels like I’m not doing what’s right she revealed a male co-star once told her Hollywood continue in the world if I don’t educate myself. he wouldn’t date her because she was speaking up about If it’s important, I’ll speak about it. “too big”) and LGBTQ rights (she has two issues around I don’t think about whether that hurts gay brothers) to politics (she campaigned sexual harassment, my career or not.” for Hillary Clinton last year). “I do feel misogyny and Since breaking out as the lead in the a duty to speak out on these things,” inequality, it foul-mouthed, anti-superhero movie Moretz says. “Of course I want to turn becomes clear, in Kick-Ass in 2010 – filmed when she was my phone off and run away, and stick retrospect, that Chloë Grace Moretz 13 – Moretz has arguably drawn more my head in the sand. But you can’t; wasA sounding the alarm all along. attention for her honesty than she has you have to do something.” Aged just 20, she has made a name for her CV, which is peppered with big When Stellar meets the actor, she is for herself by not being afraid to Hollywood epics (Hugo), standard horror attending a rain-drenched party at New MORETZ FOR GRACE publicly lead the charge as a vibrant fare (remakes of The Amityville Horror York’s High Line (an abandoned freight Ë and socially engaged young voice for and Carrie) and comedies on both the big train track turned into an elevated park) the industry’s younger generation. -

'Assassinated' War Correspondent Marie Colvin, Lawsuit Filed by Her Relatives Claims

Feedback Tuesday, Apr 10th 2018 12AM 64°F 3AM 57°F 5-Day Forecast Home U.K. News Sports U.S. Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Columnists DailyMailTV Latest Headlines News World News Arts Headlines Pictures Most read Wires Coupons Login ADVERTISEMENT As low as $0.10 ea STUDENT Ribbon Learn More Assad's forces 'assassinated' Site Web Enter your search renowned war correspondent Marie ADVERTISEMENT Colvin and then celebrated after they learned their rockets had killed her, lawsuit iled by her relatives claims President Bashar Assad's forces targeted Marie Colvin and celebrated her death This is according to a sworn statement a former Syrian intelligence oicer made The 55-year-old Sunday Times reporter died in a rocket attack in Homs By JESSICA GREEN FOR MAILONLINE PUBLISHED: 14:25 EDT, 9 April 2018 | UPDATED: 16:14 EDT, 9 April 2018 65 175 shares View comments Syria President Bashar Assad's forces allegedly targeted veteran war correspondent Marie Colvin and then celebrated after they learned their rockets had killed her. This is according to a sworn statement a former Syrian intelligence oicer made in a wrongful death suit iled by her relatives. The 56-year-old Sunday Times reporter died alongside French photographer Remi Ochlik, 28, in a rocket attack on the besieged city of Homs. ADVERTISING Like +1 Daily Mail Daily Mail Follow Follow @DailyMail Daily Mail Follow Follow @dailymailuk Daily Mail FEMAIL TODAY The intelligence defector, code named EXCLUSIVE: Tristan Ulysses, says Assad's military and Thompson caught on intelligence oicials sought to capture or video locking lips with a brunette at NYC club kill journalists and media activists in just days before Khloe Homs. -

AA-Postscript.Qxp:Layout 1

lifestyle SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 2014 GOSSIP ée nc fia to ove his l George Clooney declares he ‘Gravity’ actor praised his fiancée in a touching speech as he collected an award at the Celebrity Fight TNight in Florence, Italy. As George took to the stage at the event on Sunday he addressed his future wife and said: “I would just like to say to my bride-to-be Amal that I love you very much and I can’t wait to be your husband.” According to E!, the human rights lawyer was very touched by the public display of affection from her handsome fiancÈ. An eyewitness said: “She seemed so touched and overwhelmed and at that moment they looked right at each other and it was as if there was no one else in the room.” It was also at the Italian gala, which was held in support of the Andres Bocelli Foundation and The Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center, that the 53-year-old star let slip that he would be getting married in Venice in a “couple of weeks”, after it was reported that the couple would have their romantic ceremony in Lake Como. He told the crowd: “I met my bride-to-be in Italy, and I will be married in Italy soon, in a couple of weeks. In Venice, of all places.” Amal was recently spotted at the Alexander McQueen headquarters, prompting speculation that she would be using the same wedding dress designer as the Duchess of Cambridge - who wore a dress designed by Sarah Burton, the creative director of the brand for her wedding to Prince William in April 2011. -

Large Print Guide

Large Print Guide You can download this document from www.manchesterartgallery.org Sponsored by While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. Since its first issue in 1916, it has assumed a central role on the cultural stage with a history spanning the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. It has reflected events shaping the nation and Vogue 100: A Century of Style has been organised by the world, while setting the agenda for style and fashion. the National Portrait Gallery, London in collaboration with Tracing the work of era-defining photographers, models, British Vogue as part of the magazine’s centenary celebrations. writers and designers, this exhibition moves through time from the most recent versions of Vogue back to the beginning of it all... 24 June – 30 October Free entrance A free audio guide is available at: bit.ly/vogue100audio Entrance wall: The publication Vogue 100: A Century of Style and a selection ‘Mighty Aphrodite’ Kate Moss of Vogue inspired merchandise is available in the Gallery Shop by Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott, June 2012 on the ground floor. For Vogue’s Olympics issue, Versace’s body-sculpting superwoman suit demanded ‘an epic pose and a spotlight’. Archival C-type print Photography is not permitted in this exhibition Courtesy of Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott Introduction — 3 FILM ROOM THE FUTURE OF FASHION Alexa Chung Drawn from the following films: dir. Jim Demuth, September 2015 OUCH! THAT’S BIG Anna Ewers HEAT WAVE Damaris Goddrie and Frederikke Sofie dir. -

Drug Dealer Jailed for Five Years for Possessing a 50,000 Volt STUN GUN Disguised As a Mobile Phone

Amazon Videos Feedback Like 2m Follow @MailOnline DailyMail Thursday, Sep 11th 2014 2PM 95°F 5PM 84°F 5-Day Forecast Home U.K. News Sports U.S. Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Columnists News Home Arts Headlines Pictures Most read News Board Wires Login Drug dealer jailed for five years for Site Web Enter your search possessing a 50,000 volt STUN GUN disguised as a mobile phone Officers found the illegal weapon at the home of Wesley Walters, 26 They searched his home after he sold an undercover officer heroin He claimed the dangerous weapon was a 'novelty item' Walters was jailed for five years for drug and weapon offences By SAM WEBB PUBLISHED: 10:36 EST, 9 January 2014 | UPDATED: 11:59 EST, 9 January 2014 4 View comments A drug dealer has been jailed for five years for possessing a dangerous stun gun disguised as a mobile phone, according to police. Officers discovered the weapon, which is capable of discharging 50,000 volts, while searching the home of Wesley Walters in Southampton, Hampshire. The potentially lethal device - designed to look like the Sony Ericsson K95 - is as powerful as a standard-issue police Taser. The 26-year-old had been arrested hours earlier after supplying four wraps of heroin to an undercover Monitor your credit. Manage officer ass part of Operation Fortress, a police campaign to clamp down on serious violent crime linked your future. Equifax Complete™ Premier. to drugs in Southampton. Arizona Will this stock explode? Can you turn $1,000 into $100,000? Stuck with 20th century job skills? Update your skills & boost your career prospects here. -

Chloe Grace Moretz and Brooklyn Beckham

The Celebrity Couple to Melt All Hearts: Chloe Grace Moretz and Brooklyn Beckham By Shannon Seibert Like father, like son! Brooklyn Beckham is already stealing hearts. In the latest celebrity news, David and Victoria Beckham’s oldest son is dating Chloe Grace Moretz. Moretz, 17, and Beckham, 15, have taken advantage of the time in which Beckham has been in Los Angeles. He has just returned for school in London, but according toUsMagazine.com , the celebrity couple has gone out on dates with other couples to “see where this is going to go.” The If I Stay star has also talked of taking the aspiring model to her premiere for her newest release. Best of luck to our newest lovebirds! Celebrity couples have to worry about avoiding magazine covers, but how can you keep your new relationship and love from attracting rumors? Cupid’s Advice: No one wants to be on the receiving end of bad gossip, but by word of mouth, rumors travel at lightening speed. And where rumors start, doubt and insecurities seem to follow. You don’t need anyone sticking their nose in your business, so consider this dating advice to keep your relationship and love private! 1. Don’t publicize your concerns in your relationship:In your relationship, there are only two people: you and your partner. That being said, everyone else’s opinions on what may or may not be going on are irrelevant. There is no need for you to be sharing the intimate details of your relationship to anyone else. If something is going on, talk to your partner, not the world. -

SLS-Sept2016 1505575613.Pdf

LifeStyle EDISI 88 : SEPTEMBER 2016 MANAGEMENT 118 Tips Memanfaatkan Kartu Kredit CIMB Niaga-ACA HEALTH 120 Manfaat Minyak Zaitun untuk Kesehatan PlaCes OF INTERest 122 Tuscany CULINARY 126 Sentuhan Modern Hidangan Italia INSURANCE 128 Sedia Jaminan Kesehatan RISK MANAGEMENT 130 Longsor Yang Berbeda MISCellaneOUS 132 Milan Pusat Fashion BOOK 136 COLOR Me Series A Zen Coloring Book INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 138 Streaming Movie Berbayar INSURANCE EDUCATION 140 Prinsip Subrogasi OTOMOTIF 142 Mobil Seksi Asal Italia HIGHLIGHT Kids Corner 146 Sport 148 Smart Info 150 Insurance Ville 154 Banjir Hadiah dengan Poin Reward dari ACA 156 MAG MAL SEPTEMBER 2016 SMART LIFESTYLE 117 LifeStyle Management Tips Memanfaatkan Kartu Kredit CIMB Niaga - ACA Kartu kredit CIMB Niaga - ACA telah diluncurkan beberapa waktu yang lalu dan sudah dapat dimiliki oleh keluarga besar ACA. Kehadiran kartu kredit ini diharapkan dapat memberikan kemudahan dan manfaat, terlebih bagi karyawan/ti yang membutuhkan solusi pembayaran yang praktis dan menguntungkan. ada rubrik kali ini, kita akan Saat berjalan-jalan di luar negeri, Anda temukan pada Situs Kartu CIMB membahas tips-tips yang dapat jangan lupa untuk selalu menggunakan Niaga. Pdiikuti oleh pemegang kartu kredit kartu kredit CIMB Niaga - ACA untuk CIMB Niaga - ACA sehingga kehadiran berbelanja maupun tarik tunai. Hal 4. Kemudahan pembayaran kartu kredit ini dapat dimanfaatkan ini karena nilai tukar mata uang yang Denda atas keterlambatan secara maksimal dan memberikan diberikan oleh kartu kredit ini terbukti pembayaran dapat dihindari dengan banyak keuntungan bagi penggunanya. paling rendah dan sudah dibuktikan selalu membayar tagihan dengan tepat Simak beberapa tips berikut ini: oleh banyak penggunanya. Anda setiap bulannya. Yang perlu dipahami dapat mencoba membandingkan nilai adalah, sebetulnya pemegang kartu 1. -

Personal Named Entity Linking Based on Simple Partial Tree Matching and Context Free Grammar

Personal Named Entity Linking Based on Simple Partial Tree Matching and Context Free Grammar Sirisuda Buatongkue Department of Computer Science Heriot-Watt University This thesis is submitted for Doctor of Philosophy April 2017 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my loving parents ... Declaration I hereby declare that except where specific reference is made to the work of others, the contents of this dissertation are original and have not been submitted in whole or in part for consideration for any other degree or qualification in this, or any other University. This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration, except where specifically indicated in the text. Sirisuda Buatongkue April 2017 Acknowledgements I would like to express my grateful to the following: First and foremost I would like to thank Dr. Lilia Georgieva, my supervisor, for her encouragement, patience, expert advice and personal support. Secondly, my two examiners have also helped shape this thesis, so would like to express my deep gratitude to Valentina Dagiene and Idris Skloul Ibrahim for their time, guidance, effort and care. Thirdly, Ministry of Science and Technology and Thai Government Student’s Office for financial support and encouraging throughout my PhD studies. Finally, special thanks go to my friends, my teachers and family who have supported me throughout my research. Abstract Personal name disambiguation is the task of linking a personal name to a unique comparable entry in the real world, also known as named entity linking (NEL). Algorithms for NEL consist of three main components: extractor, searcher, and disambiguator. -

The 30 Most Influential Teens of 2017

The 30 Most Influential Teens of 2017 By TIME STAFF Updated: November 3, 2017 11:53 AM ET | Originally published: November 2, 2017 To determine TIME’s annual list, we consider accolades across numerous fields, global impact through social media and overall ability to drive news. In the past, we’ve recognized everyone from singer Lorde to Olympic champion Simone Biles to political activist Joshua Wong. Here’s who made this year’s cut (ordered from youngest to oldest): Millie Bobby Brown, 13 Not many actors can say they got an Emmy nomination, and worldwide fame, for convincing the world that they have superpowers. Brown can, thanks to her role on Netflix’s sci-fi ’80s-nostalgia-fest Stranger Things. She plays Eleven, a mysterious girl—part science experiment, part prodigy, part awkward teen—who uses telekinesis to ward off evil. But there’s remarkable nuance in Brown’s performance, the kind that is able to convey melancholy beneath magic. It has made Eleven the standout character on a show brimming with them, one who inspires Internet memes, Halloween costumes and newfound interest in Eggo waffles (Eleven’s favorite food). Brown’s own profile has risen as well. Since the show’s July 2016 debut, the British actor has rapped at the Golden Globes, signed with IMG Models and appeared on the covers of Entertainment Weekly, InStyle and more. One secret to Brown’s success? Not overthinking her craft. “Eleven is part of me and always will be. I don’t try with her,” she told TIME during a Stranger Things set visit earlier this year. -

LIV TYLER Around a Lotaround7 a Lot7

16 ............... Sunday, September16 29,............... 2019 Sunday, September 29, 2019 1GM 1GM 1GM 1GM Sunday, September 29, 2019 ...............Sunday,17 September 29, 2019 ............... 17 HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD STAR ON STAR LIFE ON IN LIFEBRITAIN IN BRITAIN WITH WITHHER HER SOCCER-LOVING SOCCER-LOVING FAMIILY FAMIILY OUT . Dave and Liz at Brooklyn Beckham’sOUT . bookDave launchand Liz at BrooklynSEX SYMBOLBeckham’s . .book . Liv launchis the face of undiesSEX firmSYMBOL Triumph . Livand is poses the face in its of range undies last firm year Triumph andSOCIAL poses inGROUP its range . last. Liv year with pals, ‘hubby’SOCIAL Dave GROUP and Becks . Liv with pals, ‘hubby’ Dave and Becks Football?Football? I can’t I can’t comprehendcomprehend it it ‘REAL GENTLEMAN’ . Twitter post‘REAL of Liv GENTLEMAN’ with her London . .buddy Twitter Becks post in of 2015 Liv with her London buddy Becks in 2015 6I don’t really6I don’t really understandunderstand what is goingwhat is going likelik Beckhame Beckham on, except on, except that they runthat they run HE STILLHE MAKES STILL MEMAKES WATCH ME ITWATCH SAYS ITLIV SAYS TYLER LIV TYLER around a lotaround7 a lot7 movie Ad Astra, opens up for moviethe much.Ad Astra, And Iopens love thatup forthey the lovemuch. it.” herAnd first I love marriage that they to rockerlove it.” Roystonher first marriage togood rocker presents. Royston good presents. vast. I do miss things challengingvast. thingI do missin my things life, I challenginghave a thing in my life, I have a HOLLYWOOD A-lister HOLLYWOODLiv EXCLUSIVE -

Aged Care Worker Simon Prodanovich Raped Grandmother in Her Own Bed | Daily Mail Online

21/10/2019 Aged care worker Simon Prodanovich raped grandmother in her own bed | Daily Mail Online Monday, Oct 21st 2019 4PM 20°C 7PM 13°C 5-Day Forecast Home U.K. U.S. News World News Sport TV&Showbiz Femail Health Science Weather Video Travel DailyMailTV Royal Family Breaking News News World News Sydney Melbourne Brisbane New Zealand Headlines Wires AFL NRL Login Ad 20 Ingenious Inventions 2019 They're selling like crazy.Everybody wants them. VISIT SITE EXCLUSIVE: Aged care worker Site Web Enter your search 'mercilessly' raped grandmother, 83, in her own bed after he wheeled out her disabled husband from the couple's bedroom Simon Prodanovich, 59, raped a sick and elderly woman inside her own home The grub had been employed as an in-home aged care worker when he struck Prodanovich's 83-year old victim is now petrified of men and lives in fear The aged care worker accused victim of framing him before DNA exposed him ENTER HERE Prodanovich faces anywhere up to 25 years in jail for his 'despicable' offending By WAYNE FLOWER IN MELBOURNE FOR DAILY MAIL AUSTRALIA PUBLISHED: 15:25 AEDT, 21 October 2019 | UPDATED: 15:27 AEDT, 21 October 2019 3.7k shares View comments An elderly grandmother of eight was raped in her own bed by her in-house carer after the 'despicable' predator wheeled her disabled husband out of their bedroom. As the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety continues around Australia, Daily Mail Australia can reveal a shocking case of cruelty against an 83- year old woman.