K. FOREIGN ACTIVITIES of DOMESTIC CHARITIES and FOREIGN CHARITIES by James F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helping Your Clients Achieve Their Philanthropic Goals

HELPING YOUR CLIENTS ACHIEVE THEIR PHILANTHROPIC GOALS MARVIN E. BLUM, JD/CPA THE BLUM FIRM, P.C. [email protected] 777 Main Street, Suite 700 Fort Worth, Texas, 76102 (817) 334-0066 October 26, 2016 www.theblumfirm.com © 2016, The Blum Firm, P.C. All rights reserved. Helping clients achieve their charitable planning goals is a labor of love. Talking with them breaks down into Who, When, How, What, and Why. WHO: Which clients do you talk with about this? WHEN is the right time for this conversation? HOW do you present the information? WHAT techniques do you discuss? WHY should clients consider including charitable planning in their estate plan? WHY should advisors bring it up? 1 WHO? Which clients do you talk with about charitable planning? Everyone, not just the mega wealthy. The techniques may differ, but everyone can include charitable planning in their estate plan. Talk to clients who already give to charity each year or regularly tithe. They may want the charities they care about remembered at their death. Talk with your clients who have already provided for their families. Those who have already done gift planning to set aside for their family may be more receptive to providing for the community. 2 Talk with clients with high-wage-earning children. Children who are financially independent are less in need of an inheritance. There’s a growing population of clients with no children. Encourage them to find what’s meaningful to them. 3 WHEN? When is the right time to talk with your client about this? Not too early in the relationship with your client. -

Running Your Own Charity: Legal Basics of Private Foundations

Running Your Own Charity: Legal Basics of Private Foundations BOSTON | CONNECTICUT | FLORIDA | NEW JERSEY | NEW YORK | WASHINGTON, DC | www.daypitney.com Table of Contents PAGE 4 OVERVIEW PAGE 7 TRANSACTIONS WITH DISQUALIFIED PERSONS: SELF-DEALING PAGE 7 Sale, Exchange, or Leasing of Property PAGE 7 Lending of Money or Other Extension of Credit PAGE 8 Furnishing of Goods, Services, or Facilities PAGE 8 Payments of Compensation or Expenses PAGE 9 Other Transfer or Use of the Income or Assets of a Private Foundation PAGE 9 Payments to Government Officials PAGE 11 MANDATORY DISTRIBUTIONS PAGE 12 EASY DISTRIBUTIONS, HARDER DISTRIBUTIONS, AND TAXABLE EXPENDITURES PAGE 12 Grants to Organizations PAGE 12 The New Exception: Grants to “Type III” Supporting Organizations That Are Not “Functionally Integrated” Are Not Qualifying Distributions and Are Taxable Expenditures PAGE 14 Grants to Individuals PAGE 14 Expenditures for Non-Charitable Purposes PAGE 14 Influencing Legislation PAGE 15 Influencing Elections and Carrying On Voter Registration Drives PAGE 15 Penalties for Taxable Expenditures PAGE 16 EXCESS BUSINESS HOLDINGS PAGE 17 JEOPARDIZING INVESTMENTS PAGE 19 INVESTMENT INCOME TAX PAGE 20 FEDERAL TAX RETURN FILING AND PUBLICITY REQUIREMENTS PAGE 21 APPENDIX DAY PITNEY LLP LEGAL BASICS OF PRIVATE FOUNDATIONS 3 Running Your Own Charity: Legal Basics of Private Foundations IRS Circular 230 Notice: Any tax advice provided herein (including any attachments) is not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed on any taxpayer. OVERVIEW Private foundations are exempt from federal income It helps to understand the rationale behind the rules. -

A Potpourri of Charitable Planning Tricks and Traps

A Potpourri of Charitable Planning Tricks and Traps Lawrence P. Katzenstein Thompson Coburn, LLP One U.S. Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63101 (314) 552-6187 [email protected] Lawrence Katzenstein is a nationally known authority on estate planning and philanthropic planning, and advises planned giving programs at institutions nationwide. He is a frequent speaker on professional programs, appearing annually on several American Law Institute estate planning programs, and has spoken at many other national tax institutes, including the Notre Dame Tax Institute, the University of Miami Heckerling Estate Planning Institute and the Southern Federal Tax Institute. Mr. Katzenstein has served as an adjunct professor at the Washington University School of Law where he has taught both estate and gift taxation and fiduciary income taxation. A former chair of the American Bar Association Tax Section Fiduciary Income Tax Committee, he is also active in the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel (ACTEC) charitable planning committee. Mr. Katzenstein was named the St. Louis Non-Profit/Charities Lawyer of the Year in 2011 and 2015, and the St. Louis Trusts and Estates Lawyer of the Year in 2010 and 2013 by Best Lawyers in America® and was nationally ranked in the 2009-2018 editions of Chambers USA for Wealth Management. He serves on the advisory board of the National Center on Philanthropy and the Law at New York University. Mr. Katzenstein is also the creator of Tiger Tables actuarial software, which is widely used around the country by tax lawyers and accountants. He received his undergraduate degree from Washington University in St. -

General Explanation of Charitable Remainder Trusts and Private Foundations

General Explanation of Charitable Remainder Trusts and Private Foundations THE USE OF CHARITABLE TRUSTS can provide investment diversification without taxable gain, a larger stream of income during life, and an income tax deduction to the maker of the charitable trust. There is considerable flexibility in designing charitable remainder trusts and they are especially attractive to high net worth individuals who wish to use them in connection with their own private foundation which, in effect, passes control of the transferred assets to the next generation for their continued charitable purposes. CHARITABLE REMAINDER TRUSTS There are two basic types of charitable remainder trust: the “charitable remainder annuity trust” (CRAT) or a “charitable remainder unitrust” (CRUT). The difference between the two types of charitable remainder trusts is that in an “annuity trust” the annuity paid to you by the trust is based on a fixed percentage of the trust assets valued at the time the assets were contributed to the trust. You would continue to receive this fixed annuity amount for the rest of your life, A “unitrust’ is designed so that the trust assets would be valued each year and you would receive a fixed percentage of the changing value of the trust as it grows (or decreases) from year to year. In other words, the “annuity trust” is a fixed annuity and the “unitrust” is a variable annuity. The payout percentages to you may be at different interest rates (i.e., 6%, 7%, 8%, 9% and 10%). You can choose any of these rates; however, the greater the amount you retain as an annuity from the trust (whether a “unitrust” or an “annuity trust”), the less will ultimately pass to charity and the lower your income tax deduction for your gift to the charitable remainder trust. -

Giving Season 2019: Gifts That Transform, and Transformed by Giving

GIVING SEASON 2019: GIFTS THAT TRANSFORM, AND TRANSFORMED BY GIVING Giving season is upon us. And there is some catching up to SUZANNE L. SHIER do. Giving in 2018 dipped slightly from 2017, which begs the Chief Wealth Planning and Tax Strategist question: How will 2019 measure up? Gifts have the power to transform. And the transformation is bidirectional, impacting the recipient and the donor. Philanthropy also has the additional beneft of being tax-favored for individuals, corporations and estates at death. With talk of a wealth tax on the campaign trail, would there be a charitable deduction to such a potential tax? CONSIDERATIONS FOR MAKING TRANSFORMATIONAL GIFTS ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF TRANSFORMATIONAL GIFTS Intentional giving has the potential to impact individuals, families and communities – everything from education to health to the arts. Consider education, often viewed as a gateway to opportunity. While giving to education accounted for 14% of giving in 2018 and totaled $58.72 billion, this amount represents a 13% decline from 2017.i As colleges and universities seek to make higher education accessible without regard to family income or wealth, the importance of endowment to bridge the funding gap has escalated. While the need has been flled with transformational gifts at some schools,ii many are earnestly seeking endowment resources. When making gift choices, impact matters. An individual life changed, a family, a community. Improved education levels, health, standards of living. Impact data is available for education, health and other areas of giving. Northern Trust 1 GIVING SEASON 2019: GIFTS THAT TRANSFORM, AND TRANSFORMED BY GIVING It can pay to do research. -

Choosing Among the Private Foundation, Supporting Organization and Donor-Advised Fund 1

CHOOSING AMONG THE PRIVATE FOUNDATION, SUPPORTING ORGANIZATION AND DONOR-ADVISED FUND 1 VICTORIA B. BJORKLUND SIMPSON THACHER & BARTLETT LLP MAY 29, 2003 This outline focuses on factors a donor should consider in choosing among the private foundation, supporting organization and donor-advised fund. The outline also examines current developments regarding private foundations, supporting organizations, and donor- advised funds. The emergence of the donor-advised fund in the 1990s marks a dramatic change in the American charitable-giving paradigm. Now virtually every exploratory conversation between an advisor and a prospective donor includes discussion of the donor-advised-fund option. The donor-advised fund focuses on values important to contemporary donors: involvement and efficiency2 and all with significantly lower operating costs than would apply to a private foundation or supporting organization. Part of donor-advised funds’ appeal is their ease of use: donors can open a gift account without any advice of counsel or legal instruments. Many accounts can easily be opened online. 1 Copyright © 2003 Victoria B. Bjorklund. This outline builds upon “The Emergence of the Donor- Advised Fund,” presented at Georgetown University’s 15th Annual Conference on Representing and Managing Tax-Exempt Organizations and reprinted at 3 Paul Streckfus’ EO Tax Journal 15 (May 1998), prior outlines on this topic published by ALI-ABA, and a paper delivered at the October 1999 meeting of The National Center on Philanthropy and the Law at NYU Law School, which was published in 27 E.O.T.R. 107 (Jan. 2000). 2 See, e.g., “‘Wired’: Giving With a Bottom Line,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, p. -

Foundation Exempt from Income Tax, 990-PF, and the Annual Report Of

DOCOIERT ABSORB. ED 158 755 -1p 006 356 AUTHOR Machalow, Robert '0 TITLE Information, on Private Foundaticins; An Introduction to Interpreting Their Internal RevenUe Service I. Returns. PUB DATE -77 NOTE 18p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.83 HC-$1.67 Plus Postage.. DESCRIPTORS *Financial Policy; *Grants; Indexes (Locaters) ; Information Utilization; *Private .Agencies; *Records. (Forms) ; Tables (Data); Taxes ABSTRACT Forms filed annually b' .private foun ations with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS),. namely the Return of Private Foundation Exempt from Income Tax, 990-PF, and the Annual Report of Private Foundation, 990-AR, contain valuable information,which may reveal the sccpe and purpose of,a foundation's past grants. This Ars only reliable way to ascertain the foundation's areas. of interest. This,information-is available directly through the IRS, the Foundation Directory,,the"Foundation Grants Index, and the FoUndation Center Source Book Profiles. Ipcluded in this paper is aA.ist pihpointing information of importance to grant seekers available on the 990-PF and AR forms, and exactly where on the forms this information can be found. Sample= forms' are included. (MBRy *** ****************************************************************** * Reprodacti9ns supplied by EDRS, are, the best that can be made - * .. *, -1 from - t'h'e original document. , * - * * * * * * * * * ** * * * * * * I. * * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * : U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION 8, WELFARE t NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT-CHAS BEEN REPRO- ' DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN- ATING LT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATEC.D0 NbT NECESSARILY REPRE-. SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY INFORMATION ON PRIVATE 'FOUNDATIONS: AN INTRODUCTION TO INTERPRETING. THEIR INTERNAL , REVENUE SERVICE RETURNS I . -

Public Charity Or Private Foundation Status Issues Under IRC 509(A)(1)-(4), 4942(J)(3), and 507

Public Charity or Private Foundation Status Issues under IRC 509(a)(1)-(4), 4942(j)(3), and 507 By Virginia G. Richardson and John Francis Reilly Exempt Organizations-Technical Instruction Program for FY 2003 Public Charity or Private Foundation Status Issues under IRC 509(a)(1)-(4), 4942(j)(3), and 507 By Virginia G. Richardson and John Francis Reilly Overview Purpose This article presents an overview of the issues confronted when dealing with whether an organization is a public charity or a private foundation, whether it is a private operating foundation, and what are the rules regarding termination of private foundation status. Introduction: To a great extent, the Tax Reform Act of 1969 is based on the distinction Public between private foundations and public charities. Private foundations are Charity/Private subject to the excise taxes imposed by IRC chapter 42, while public charities Foundation are not. It is, therefore, most advantageous for an IRC 501(c)(3) organization Distinction to be classified as a public charity rather than as a private foundation. In This Article This article contains the following topics: Topic See Page Overview 1 Organizations That Engage in Inherently Public Activity (IRC 7 509(a)(1) and 170(b)(1)(A)(i)-(v)) IRC 170(b)(1)(A)(ii) Exclusion - Certain Educational 16 Organizations IRC 170(b)(1)(A)(iii) Exclusion - Hospitals and Medical Research 27 Organizations IRC 170(b)(1)(A)(iv) Exclusion - Endowment Funds Organized 40 and Operated in Connection with State and Municipal Colleges and Universities IRC 170(b)(1)(A)(v) -

Probation Consultation Response

Strengthening Probation, Building Confidence Lloyds Bank Foundation for England & Wales’ response to the Ministry of Justice consultation 1. Summary • People in the criminal justice system face a range of complex issues that will not be addressed by linear, generic services. The new probation system needs to place the person at the centre, facilitating wrap-around, tailored support from a plurality of providers. • Scale can be achieved through working with a variety of providers. Small and local charities need to be part of an ecosystem or providers as they are able to provide specialist support to specific cohorts that reflect the relevant local context. • Small and local charities (97% of the charity sector) have a long track record of delivering quality services to people in the criminal justice system. The distinctive characteristics of these charities also enable them to deliver high levels of social value. Funding decisions need to place greater emphasis on both quality of service and the local social value delivered by providers. • Small and local charities should be engaged throughout every stage of the probation system, from system design to service delivery. Structures should be developed to facilitate ongoing engagement with small and local charities. • Learning from the challenges of Transforming Rehabilitation, the new probation system should be designed in a simple, integrated way to reduce complexity and fragmentation – coordinating with other agencies and learning from the new aligned system in Wales. • The new system should support effective collaboration and operate at a level that is most appropriate to meet local needs, with flexibility to reflect the specific contexts of local areas. -

Private Foundations Establishing a Vehicle for Your Charitable Vision “I Didn’T Know Where to Start

Private foundations Establishing a vehicle for your charitable vision “I didn’t know where to start. The advice I received on creating a private foundation pointed me in the right direction, and now I’m confident that I’ve done the right thing – both financially and philanthropically.” Content Private foundations can help individuals and families reach their philanthropic goals while offering multiple benefits along the way. There are several important decisions that need to be made before committing to establish a private foundation. Knowing what questions to ask and obtaining sound advice can assist you with the complexities of creating and maintaining a private foundation. We can help. It is vital to begin with the basics before moving forward, particularly relating to: • The advantages and disadvantages • The types of assets you can contribute • How to form a private foundation • The potential tax implications Accomplishing your charitable vision 02 Private foundation basics 03 Tax impacts 05 Forming a private foundation 11 Accomplishing your charitable vision If you think you might be ready to establish a private foundation, you must objectively consider why a private foundation makes sense for you or your family. Is a private foundation right for you? Do you or your family: • Have a charitable vision? • Want to control the timing and use of your charitable funds? • Want to introduce children and grandchildren to philanthropy? • Want to create a charitable legacy for your family? If you answer yes to one or more of these questions, a private foundation could be right for you. 2 Private foundation basics What is a private foundation? A private foundation is The legal and tax requirements of private foundations “Our family believes in the • A formal vehicle for charitable giving require a disciplined approach to grantmaking and importance of educating • A non-governmental, non-profit organization investment decisions. -

Top Ten Ways Family Foundations Get Into Trouble

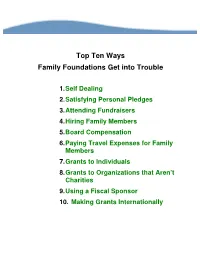

Top Ten Ways Family Foundations Get into Trouble 1. Self Dealing 2. Satisfying Personal Pledges 3. Attending Fundraisers 4. Hiring Family Members 5. Board Compensation 6. Paying Travel Expenses for Family Members 7. Grants to Individuals 8. Grants to Organizations that Aren’t Charities 9. Using a Fiscal Sponsor 10. Making Grants Internationally Self-Dealing 1. What is self-dealing? The use of foundation assets to enter into any financial transaction between the foundation and a disqualified person. Types of self-dealing transactions include the sale, exchange or lease of property, loans, extensions of credit, payments to government officials, satisfying pledges, furnishing goods or services, and more. 2. What are the penalties? Penalty on self-dealer is now 10 percent of amount involved. Penalty on foundation manager is now 5 percent . 3. Who are Disqualified persons? - Directors, Officers, Trustees - Foundation managers (such as an executive director) - Substantial contributors to the foundation ($5,000 and 2 percent rule) • Also includes family members of the persons above such as ancestors, spouse, children (and their spouses), grandchildren (and their spouses). 4. What are some examples of self-dealing? • Foundation loans $$, or furnishes goods or services to disqualified person • Foundation pays rent to disqualified person, even if below market rate • Foundation pays excessive compensation to disqualified person 5. Can we pay rent to a family member for use of their offices? No. The payment of rent would be self-dealing, even if it is below market rate. Only exception is if rent is $0 (any utilities and other costs must be paid to third party, not to family). -

Private Foundations: a Practical Guide to Key Issues, Choices, and Risks

Private Foundations: A Practical Guide to Key Issues, Choices, and Risks Darren B. Moore Megan C. Sanders Bourland, Wall & Wenzel, P.C. Fort Worth, Texas Presented to: Philanthropy Southwest and the Oklahoma Center for Nonprofits February 26, 2015 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma The information set forth in this outline should not be considered legal advice, because every fact pattern is unique. The information set forth herein is solely for purposes of discussion and to guide practitioners in their thinking regarding the issues addressed herein. Nonlawyers are advised to consult an attorney before undertaking issues addressed herein. All written material contained within this outline is protected by copyright law and may not be reproduced without the express written consent of Bourland, Wall & Wenzel. © Bourland, Wall & Wenzel, P.C. Speaker/Editor1 DARREN B. MOORE Bourland, Wall & Wenzel, P.C. 301 Commerce Street Fort Worth, Texas Phone: (817) 877-1088 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @darrenbmoore Blog: Moorenonprofitlaw.com Darren practices with Bourland, Wall & Wenzel, P.C., a Fort Worth, Texas law firm which represents individuals, closely held and family businesses, professional practices and charitable organizations within its areas of legal practice. Darren’s practice focuses on representation of nonprofit organizations, in which he advises clients on a wide range of tax and legal compliance issues including organization of various types of nonprofit entities, obtaining and maintaining tax-exempt status, risk management, employment issues, governance, and other business issues, as well as handling litigation matters on behalf of his exempt organization clients. Darren is from Lubbock, Texas and earned a B.A., cum laude, from Texas A&M University, and his J.D., magna cum laude, from Baylor Law School where he served as Editor in Chief of the Baylor Law Review.