The Criminon Program Evaluation: Phase I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

010293 Scientology

Interfaith Evangelism BELIEF Scientology BULLETIN Cults, Sects, and New Religious Movements Official Name: Church of Scientology International Founder: L. Ron Hubbard, in 1954 Current Leaders: David Miscavige, (b. 1960); Heber C. Jentzsch (b.1935) Headquarters: Los Angeles, Calif.; Clearwater, Fla. (Flag Land Base) Organizations Associated with Scientology: Applied Scholastics National Commission on Law Enforcement Association for Better Living and Education and Social Justice (ABLE) Religious Technology Center Citizens Commission on Human Rights Sterling Management Systems Concerned Businessmen’s Association of America The Way to Happiness Foundation The Hubbard Dianetics Foundation International World Institute of Scentology Enterprises (WISE) Narconon/Criminon Publishing Organizations: New Era Publications, International; Bridge Publications, Inc. Key Publications: Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health (1950) and other books by L. Ron Hubbard; What is Scientology? (1978) compiled by staff of the Church of Scientology International; Freedom magazine This Belief Bulletin highlights basic concepts of In 1954, Hubbard incorporated the Church of Scientology and gives Biblical responses. Scientology to promote his ideas using a religious facade. His books and church spread worldwide, but Hubbard History became a recluse. He spent most of his last years aboard Lafayette Ronald Hubbard was born in Nebraska in his yacht being waited on hand-and-foot. He died inaus- 1911. He spent most of his childhood on his grandfa- piciously in 1986. ther’s Montana ranch while his parents served overseas in the U.S. Navy. Hubbard later stated that visits with par- Commonly Used Scientology Terms ents to Asia in the 1920s introduced him to eastern Analytical mind: The conscious, rational, and problem philosophies and religions. -

Church of Scientology

Church of Scientology By Kurt Van Gorden Founder: Lafayette Ronald Hubbard; a.k.a., L. Ron Hubbard (1911-1986) Current Leader: David Miscavige, Chairman of the Board for the Religious Technology Center. Founding Date: 1953 Official Publications: All of L. Ron Hubbard’s books, publications, and audio messages that were produced under the auspices of Dianetics and Scientology have been officially proclaimed as scripture in the Church of Scientology. Organization Structure: Scientology church members belong to the International Association of Scientologists. The Continental Liaison Offices oversee the local missions and churches, also referred to as Ideal Churches or Ideal Orgs (organizations). The supreme church corporation is the Church of Scientology International headquarters in Los Angeles, California. Scientology’s new spiritual headquarters is located in Clearwater, Florida. Known as the Flag Building, it also serves as a land base for the highest staff positions, the maritime Sea Org, whose members wear naval-style uniforms with officer ranks. Other Organizational Names: Scientology Celebrity Centers, Citizens Commission on Human Rights, Association for Better Living and Education—ABLE, Applied Scholastics, Bridge Publications, Criminon, Narconon, Foundation for Religious Tolerance, Sterling Management, Worldwide Institute of Scientology Enterprises—WISE, and The Way to Happiness Campaign. Unique Terms: Dianetics (through the mind or soul), Scientology (knowing how to know), Thetan, Engram, Auditing, Clear, E-Meter, and Operating Thetan (OT). HISTORY L. Ron Hubbard was a successful science fiction writer who published over 15,000,000 words between 1932 and 1950 under 20 pen names. Some critics believe that Hubbard may have predicted his forthcoming church. While speaking at a 1949 New Jersey science fiction convention, Hubbard reportedly stated, “Writing for a penny a word is ridiculous. -

Utopia a Edukacja, Tom 4, Dysonanse, Kontrasty I Harmonie Wyobrażeń

UTOPIA A E D UKACJA TOM IV RED. RAFAŁ WŁODARCZYK WROCŁAW 2020 UTOPIA A EDUKACJA#4 UTOPIA A EDUKACJA tom IV DYSONANSE, KONTRASTY I HARMONIE wyobrażeń świata możliwego redakcja rafał włodarczyK Instytut PedagogIkI unIWersytetu WrocłaWskIego WrocłaW 2020 redakcja Rafał Włodarczyk recenzja prof. dr hab. agnieszka gromkowska-Melosik korekta Rafał Włodarczyk okładka Monika Humeniuk Hanna Włoch skład Hanna Włoch IsBn 978-83-62618-56-9 © Instytut Pedagogiki uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego Wrocław 2020 Instytut Pedagogiki uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego ul. dawida 1, 50-527 Wrocław tel. 71 367 32 12, [email protected] SpiS treści od redaktora 9 część I obrazy utopii a niepokoje kultury współczesnej Leszek koczanowicz Lęk jasnowidzenia. terminalne olśnienie i kres kultury 15 robert klementowski Polityka pamięci historycznej jako droga do utopii 39 dariusz Brzeziński utopijne powroty do przeszłości: młode pokolenie wobec zwrotu nostalgicznego 59 adam nobis nowy Jedwabny szlak jako utopia globalna 77 Witold Jakubowski Popkulturowe ilustracje utopii społecznych, czyli o edukacyjnym potencjale kultury popularnej 91 rafał Węgrzyn, karolina Woźny utopia – więzienie – resocjalizacja. Problem z burzycielami ładu społecznego 109 część II pedagogiczne implikacje myślenia utopijnego Maria czerepaniak-Walczak Iluzja upełnomocnienia jako środka emancypacji w edukacji i poprzez edukację 127 katarzyna szumlewicz utopia „perspektywy zdolności” Marthy nussbaum 143 andrzej sędek Między realizmem a utopizmem edwarda abramowskiego 165 Małgorzata Piasecka (geo)poetyka marzenia. utopia – heterotopia – trzecia przestrzeń 179 Marcin krassowski Laboratoria przyszłości. ekowioski jako projekty edukacyjno-utopijne 203 sergiusz anoszko Przyswajanie wiedzy w nowych ruchach religijnych: applied scholastics International ofertą edukacyjną kościoła scjentologicznego 223 część III obrazy utopii oraz ślady dystopii w praktyce edukacyjnej agnieszka dwojak-Matras, katarzyna kalinowska, agnieszka koterwas uczenie rzetelności naukowej jako dążenie do utopii. -

Benefits I Have Received from Scientology Auditing and Train

14 August 1997 Dear I have been asked to describe certain 'secular' benefits I have received from Scientology auditing and training that are not generally understood to be religious or spiritual in nature and how these have affected my community services activities. From my own schooldays I had a purpose to help other children gain a good education and to this end became a qualified teacher and pursued this profession until I married and had a family. I then came into contact with Scientology and through it gained greater self reliance and greater confidence in handling projects Also I was trained in the use of the study method developed by L Ron Hubbard and decided that I wanted to use it to help children to study better in school. With the help of a local West Indian businessman and other volunteers I started Riving supplementary teaching in the evening to disadvantaged children in Brixton , something which was especially wanted by West Indian parents in the drea. This project which we named B.E.S.T, ( the Basic Education and Supplementary Teaching .Association ) is now an authorised charity and continues to provide supplementary teaching and vacation projects in the Brixton area. More recently I have taken on another volunteer activity, that of bringing this study method to teachers in a country in Southern Africa. The education authorities in that country had become aware that the academic results being achieved in their schools were not sufficiently being translated into success in the professions and the workplace. L Ron Hubbard's Study Technology with its emphasis on fully understanding and being able to apply the data being studied was demonstrated in a pilot project and was shown to markedly increase student interest and comprehension and to greatly reduce truancy and its introduction was approved. -

Dear Matt, While I Understand Your Predicament, I Fully Understand The

Dear Matt, While I understand your predicament, I fully understand the situation you and your ASA colleagues find yourselves in. It is not often one has to deal with an organisation as deceptive as The Way To Happiness Foundation. To cut to the chase - while the ASA acknowledges the connection between The Way To Happiness Foundation and Scientology, the ASA believes that The Way To Happiness Foundation is a separate charity in its own right. I intend to present evidence establishing the following four points: 1) The Way To Happiness Foundation is under control of Scientology international management. 2) The Way To Happiness Foundation is run by Scientologists. 3) The Way To Happiness Foundation is being run for the purpose of Scientology. 4) A proportion of donations collected by The Way To Happiness Foundation go to Scientology. If the above four points are true, then the claim that The Way To Happiness Foundation is a separate charity in its own right must be rejected, and future advertisements on behalf of this group must clearly reflect this. 1. The IRS application and decision. I will begin by revisiting the IRS position. The 1023 IRS filing made in 1993 as part of The Way To Happiness Foundation’s application for tax-exemption is available from http://www.xenu-directory.net/documents/corporate/irs/1993-1023-twth.pdf . From page 10 that 1023 filing: Evidence piece 1 From page 9 of that same document: Evidence piece 2 Evidence piece 3 From the 1993 IRS closing agreement that gave The Way To Happiness Foundation and other Scientology entities their tax-exemption, Scientology-related entities qualifying for tax-exemption are defined thus (http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Cowen/essays/agreemnt.html#Scientology- related%20entity ): “4. -

Comparison Between Freedom of Religion in Germany and in the United States in General and the Treatment of the Church of Scientology Specifically

University of Georgia School of Law Digital Commons @ Georgia Law LLM Theses and Essays Student Works and Organizations 2000 COMPARISON BETWEEN FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN GERMANY AND IN THE UNITED STATES IN GENERAL AND THE TREATMENT OF THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY SPECIFICALLY WOLFGANG EICHELE University of Georgia School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/stu_llm Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Repository Citation EICHELE, WOLFGANG, "COMPARISON BETWEEN FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN GERMANY AND IN THE UNITED STATES IN GENERAL AND THE TREATMENT OF THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY SPECIFICALLY" (2000). LLM Theses and Essays. 284. https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/stu_llm/284 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works and Organizations at Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in LLM Theses and Essays by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARISON BEMI^Filii i^:;l^ IN ; GERiAIW AND IN THE UNITED sIteSS:^ IN GEERAL ;; AND THE TREATIVInT i^' Tft I ^ • : CHURCH OF SCENTOL OG Y SPEGFICALIY :ang Eichele The University of Georgia Alexander Campbell King Law Library UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA LAW LIBRARY 3 8425 00347 5154 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2013 http://arcliive.org/details/comparisonbetweeOOeicli COMPARISON BETWEEN FREEDOM OF RELIGION IN GERMANY AND IN THE UNITED STATES IN GENERAL AND 1 HE TREATMENT OF THE CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY SPECIFICALLY by WOLFGANG EICHELE 1. -

L. Ron Hubbard Common-Sense Moral Code Is the Failures of Psychiatry 36 Achieving Remarkable Success in Schools

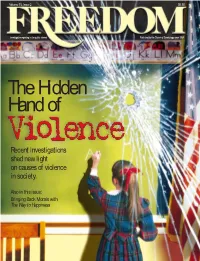

Volume 31, Issue 2 $2.50 Investigative reporting in the public interest Published by the Church of Scientology since 1968 The Hidden Hand of Violence Recent investigations shed new light on causes of violence in society. Also in this issue: Bringing Back Morals with The Way to Happiness From the Editor’s Desk has been eroded through the last four decades of “progressive education” — a system designed more for psychological conditioning than academic success. The Add the wholesale labeling of children with psychiatric “disorders” (such as “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder” and a host of “Learning Disorders”) for exhibiting much of what was previously considered normal childhood behavior. Erosion These labels not only excuse the educa- tional shortcomings of our schools, but the youth who receive them are told that they are responsible neither for what they do nor for the decisions they make. In fact, and of Right perhaps not so coincidentally, the Denver Post reported in December 1996 that federal law prohibited the expulsion of three kids who passed a gun around at school because they were classified as and “special-education” students. These stu- dents were not considered responsible for what they did. Finally, add a chemical catalyst of mind- altering psychiatric drugs and the result is volatile and even deadly. Keep in mind, too, Wrong that the types of “special education” students who are not held responsible for nalert Feeding Christians to lions was once popu- passing around deadly weapons at school columnist lar “sport.” For centuries, public executions are the ones most likely to be on such drugs. -

Surviving with Spirituality: an Analysis of Scientology in a Neo-Liberal Modern World Kevin D

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Undergraduate Research in Sociology Department of Sociology 10-13-2011 Surviving with Spirituality: An Analysis of Scientology in a Neo-Liberal Modern World Kevin D. Revier St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/soc_ug_research Part of the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Revier, Kevin D., "Surviving with Spirituality: An Analysis of Scientology in a Neo-Liberal Modern World" (2011). Undergraduate Research in Sociology. 1. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/soc_ug_research/1 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research in Sociology by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Surviving with Spirituality: An Analysis of Scientology in a Neoliberal World Abstract The neoliberal system has expanded fertile ground for markets to produce and distribute spiritual commodities. This paper examines how the Church of Scientology profits by selling spiritual goods to the modern neoliberal consumer. To accumulate data, I conducted interviews and participated in various rituals at the Church of Scientology in St. Paul, Minnesota. I outline and examine the data in four sections: the initiation process of the latent member, their consumption patterns in the Church, social interactions between members, and how these interactions bridge the Church into the public arena. I conclude that the Church is a market institution that promotes neoliberal ideology. Introduction “God is dead!” Friedrich Nietzsche declared in a narrative about a madman preaching in an 18 th century marketplace (1954: 95). -

Entity Name (BCDA) BATIBO CULTURAL and DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 01:CONCEPT LLC 1 800 COLLECT INC

Entity Name (BCDA) BATIBO CULTURAL AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 01:CONCEPT LLC 1 800 COLLECT INC. 1 CLEAR SOLUTION, LLC 10 GRANT CIRCLE LLC 10 Grant KNS LLC 1000 URBAN SCHOLARS 1001 16TH STREET LLC 1001 H ST, LLC 1001 L STREET SE, L.L.C. 1001 SE Holdings LLC 1003 RHODE ISLAND LLC 1005 E Street SE L.L.C. 1005 Rhode Island Ave NE Partners LLC 1007 Irving Street NE Partners LLC 1007-1009 H STREET, NE LLC 100TH BOMB GROUP FOUNDATION INC. 101 5th Street NE LLC 101 CONSTITUTION Trust 101 WAYNE LLC 1010 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE CONDOMINIUM UNIT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 1010 V LLC 1011 Otis Place L.L.C. 1011 Otis Place NW LLC 1012 9th St. Builders LLC 1015 Euclid Street NW LLC 1015 U STREET LLC 1016 16TH STREET CONDOMINIUM LLC 1016 7TH STREET LLC 1019 VENTURES LLC 102 MILITARY ROAD LLC 1020 45th St. LLC 1021 48TH ST NE LLC 1022 47TH STREET LLC 1026 45th St. LLC 1030 TAUSSIG PLACE, LLC 1030 W. 15TH LLC 1033 BLADENSBURG ROAD, NE LLC 1035 48th Street LLC 104 13TH STREET LLC 104 Kennedy Street LLC 1042 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP LLP 105 35th Street N.E. LLC 1061 INN, LLC 107 LLC 1070 THOMAS JEFFERSON ASSOCIATES LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1075 KENILWORTH AVENUE LLC 1085805 SE LLC 1090 Vermont LLC 1090 VERMONT AVENUE GP LLC 109-187 35TH STREET N.E. BENEFICIARY LLC 109-187 35TH STREET N.E. TRUSTEE LLC 10TH & M STREET CONDOMINIUMS LLC 10th Street Parking Cooperative Association, Inc. 1100 21ST STREET ASSOCIATES LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1100 FIRST INC. -

A Broader Look at the Organization

Sci-organization (Converted)-1 3/6/98 3:01 PM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K SIGNS AND SYMBOLS: This signs adorns the Church of Scientology at 448 Beacon St. L. Ron Hubbard A broader (1911-1986) Created Church of look at the Scientology, 1953; wrote bestseller organization “Dianetics,” 1950. Applied Scholastics Sacred scriptures Groups selling Hubbard’s Study Technology in 156 schools in 31 countries; actress Anne Archer is spokeswoman Church of Spiritual Technology (preserves David Miscavige Hubbard archives in earthquake-proof vaults) Ability schools Hubbard’s heir; joined as a teenager L. Ron Hubbard Library (owns copyrights) Apple schools Religious Technology Center Author Services Inc. (literary agency) Bear Hill School Inc. in Pittsfield, N.H. Has supreme control over entire Bridge Publications (sells U.S. books, E-Meters) organization; enforces purity of the religion Association Boston Academy School in Somerville Golden Era Productions (sells films; produces through trademark and copyright lawsuits for Better Community Service Guild (tutors inner-city children) TV ads) — and its Inspector General Network; Living and Delphi Academy in Milton and six other U.S. locations; New Era Publications (worldwide book sales) Miscavige is RTC chairman of board. Education headquarters in Oregon International Association for Effective Education (teaches (oversees the schoolteachers) church’s anti- Spinoff groups of Scientologists Training and recruitment World Literacy Crusade in Brighton and 25 other U.S. cities promoting and selling Hubbard’s drug and network education (sells Study Technology; Isaac Hayes is spokesman) Purification Rundown Guillaume Lesevre, international director groups) Foundation for Advancements in Science and Church of Scientology International Groups selling or promoting Hubbard’s Education in Los Angeles (does Purification The Mother Church; located in Los Purification Rundown detox method Rundown research and makes children’s PBS- Angeles; Lesevre is director, Rev. -

Church of Scientology Judicial Review

HO.ME OFFICE - Feu 03 0001/0029/003/ -.." RELATED PAPERS FILE BEGINS: __ __ ENDS: FILE TITLE: - : POLICY (REVIEW AFTER 25 YEARS) CULTS I NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS s: . '- CHURCH OF SCIENTOLOGY JUDICIAL REVIEW - SEND TO I DATE - SEND TO DATE SEND TO -- DATE . ZO,3 -. , - -- 0 0 - -- 0 . 0 - " -0 . 0 0 -- 0 HOF000647241 ese 8111 .. .. --- _ .. - - - -- - -- - _. , - AnnexA Press Office to take Subject: Judicial Review Case: Recognition of Scientology as a religion in prison Tuesday 21 October - permissions hearing for a judicial review on HRA grounds of Prison Service policy not to recognise Scientology as a religion for the purpose of facilitating religious ministry in prisons. Background Prisoner Roger Charles Heaton and the Church of Scientology have made an application for jUdicial review of this policy. Unes to take The applicants, having seen our witness statement and outline argument, have offered to withdraw their case, with no order as to costs. This means that the non-recognition policy being followed by prison service is reasonable .and secure. It has been our long-standing policy to withhold recognition of scientology as a religion. However, in order to meet the needs of individual prisoners, the Prison Service allows any prisoner registered as a Scientologist to have access to a representative of the Church of Scientology if he wishes to receive its ministry. This is the approach which was followed in the case of Mr Heaton. The Home Office considers that its policy respects the rights of Mr Heaton under the ECHR and is reasonable in view of concerns of which the department is aware about some of the practices of the Church. -

The Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology | Profile | Beliefs | Current Issues | Links | References | I. Group Profile | Biography | History | Sacred or Revered Texts | Size | Organization | 1. Name: Church of Scientology Scientology means "knowing about knowing," from the Latin word scio and the Greek word logos. 1 2. Founder: Lafayette Ronald (L. Ron) Hubbard 3. Date of Birth/Death: March 13, 1911/January 24, 1986 4. Birth Place: Tilden, Nebraska 5. Year Founded: 1954 6. Biography of Founder: According to texts published by the Church of Scientology and its web page pertaining primarily to its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, always referred to as L. Ron by Scientologists, experienced early in his life the many facets of the human mind. At the age of 12, he learned from Commander Joseph C. Thompson, who was the first military official to study under Sigmund Freud in Vienna, Austria, the theory of psychoanalysis. Hubbard was also influenced by his many world journeys to exotic locales, thus gaining an appreciation for Eastern philosophies rooted in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism. His studies in mathematics, engineering, and nuclear physics at George Washington University generated a scientific background to his beliefs in the human mind, although his studies did not earn him a degree. As a naval officer during World War II, he suffered injuries that left him blind and crippled. During his recovery, he once again examined Freudian psychoanalytical theory and Eastern philosophies. He credits the eventual cure of his disabilities to his findings about the human mind during this time, findings that became the central elements of a religious doctrine he later called Dianetics.