Falkland Islands Implementation Plan for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HARDY FAMILY VERSION: 7 March 2017 HARDY FAMILY

HARDY FAMILY VERSION: 7 March 2017 HARDY FAMILY NB: The following is prepared from Falkland Islands Registers and files – there may be other family born outside the Falklands. Unless stated otherwise, all dated births, deaths and marriages occurred in the Falklands and all numbered graves are in Stanley Cemetery. Various spellings of names are recorded as written at the time. Frederick HARDY was married to Eliza CONGDEN (not in the Falkland Islands). Frederick arrived in the Falkland Islands in 1864. He most likely would have come out with the detachment of Marines under the command of Lieutenant G H Elliott. This detachment consisted of 1 lieutenant, 1 sergeant, 1 corporal and 18 privates who received pay equal to their ordinary pay, rations, quarters plus 2 shillings a day whenever they were employed as labourers. A military detachment was considered necessary in the Colony as they were considered “indispensable on account of the large resort of British and Foreign Merchantmen, and Whalers, and of the necessity of having some force to maintain order amongst them and to secure respect for the laws of the Colony”. [F12] The detachment left the Thames, England, on board the freight ship “Velocidade” on the 29th October 1863 and the officers and their families were listed as 1 officer and 1 lady, with the troops and their families listed as 20 men, 6 women and 8 children. The “Velocidade” arrived in Stanley 8 January 1864 after a voyage of 63 days. By 1868 the available accommodation for the detachment consisted of 8 wooden cottages, a barrack room capable of containing 12 single men or 2 married men and a row of 10 “excellent” stone cottages, commenced in 1861 and recently completed in 1868”. -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Vocal Communication of Falkland Skuas

Simona Sanvito and Filippo Galimberti Elephant Seal Research Group Vocal communication of Falkland skuas Project report - 2016/2017 Address for correspondence: Dr. Simona Sanvito, ESRG, Sea Lion Island, Falkland Islands; Phone +500 32010, Fax +500 32003 Email [email protected] www.eleseal.org Summary The Falklands skua is an important, but understudied, component of the Falklands marine megafauna and biodiversity. We carried out field work on skuas at different locations in the Falkland Islands (Sea Lion Island, Carcass Is., Saunders Is., Bleaker Is., Pebble Is. and Islet, and Steeple Jason Is.) during the 2016-2017 breeding season. We recorded skuas vocalizations in all studied sites, to follow up our project on vocal communication started in 2014 at Sea Lion Island, and we also collected preliminary data on nests location and habitat, and spatial distribution at large, at the different sites. In this report, we present the results of the field work, we summarize the nesting and breeding data, and we present some preliminary findings about the communication study. We found that skuas are actually breeding in places where they were not known to do so (e.g., Pebble Is.), and in some places we found a spatial distribution quite different from what we expected, based on traditional knowledge (e.g., at Carcass Is.). We observed a large variation in the timing of breeding between the islands. We confirmed that skuas have a complex vocal communication system, that there is individual variation in vocal behaviour and vocal reactivity of different individuals, and that calls have important individual features. We also drafted a preliminary vocal repertoire for the species, and we found that the contact call seems to be the best part of the repertoire to study individual recognition. -

Gondwana Break-Up Related Magmatism in the Falkland Islands

1 Gondwana break-up related magmatism in the Falkland Islands 2 M. J. Hole1, R.M. Ellam2, D.I.M. MacDonald1 & S.P. Kelley3 3 1Department of Geology & Petroleum Geology University of Aberdeen, AB24 3UE, UK 2 4 Scottish Universities Environment Research Centre, East Kilbride, Glasgow, G75 0QU, UK 5 3 Department of Earth & Environmental Sciences, Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA 6 UK 7 8 Jurassic dykes (c. 182 Ma) are widespread across the Falkland Islands and exhibit considerable 9 geochemical variability. Orthopyroxene-bearing NW-SE oriented quartz-tholeiite dykes 10 underwent fractional crystallization > 1 GPa, and major element constraints suggest that they 11 were derived by melting of pyroxenite-rich source. They have εNd182 in the range -6 to -11 and 87 86 12 Sr/ Sr182 >0.710 and therefore require an old lithospheric component in their source. A suite 13 of basaltic-andesites and andesites exhibit geochemical compositions transitional between Ferrar 14 and Karoo magma types, and are similar to those seen in the KwaZulu-Natal region of southern 15 Africa and the Theron Mountains of Antarctica. Olivine-phyric intrusions equilibrated at < 0.5 87 86 16 GPa, and have isotopic compositions (εNd182 1.6-3.6 and Sr/ Sr182 0.7036-0.7058) that require 17 limited interaction with old continental lithosphere. A suite of plagioclase-phyric intrusions with 87 86 18 Sr/ Sr182 c. 0.7035 and εNd182 c. +4, and low Th/Ta and La/Ta ratios (c. 1 and c. 15 19 respectively) also largely escaped interaction with the lithosphere. These isotopically depleted 20 intrusions were probably emplaced synchronously with Gondwana fragmentation and the 21 formation of new oceanic lithosphere. -

A Review of the Abundance and Distribution of Striated Caracaras Phalcoboenus Australis on the Falkland Islands Micky Reeves &Am

A review of the abundance and distribution of Striated Caracaras Phalcoboenus australis on the Falkland Islands Aniket Sardana Micky Reeves & Sarah Crofts Falklands Conservation, May 2015 The authors dedicate this report to Mr. Ian Strange and Mr. Robin Woods whose earlier surveys laid much ground work. This work was funded by: Falklands Conservation is a company limited by guarantee in England & Wales #3661322 and Registered Charity #1073859. Registered as an Overseas Company in the Falkland Islands. Roy Smith “These birds, generally known among sealers by the name of “Johnny” rook, partake of the form and nature of the hawk and crow… Their claws are armed with large and strong talons, like those of an eagle; they are exceedingly bold and the most mischievous of all the feathered creation. The sailors who visit these islands, being often much vexed at their predatory tricks, have bestowed different names upon them, characteristic of their nature, as flying monkeys, flying devils….” Charles Bernard 1812‐13 “A tameness or lack of wariness is an example of the loss of defensive adaptations.... an ecological naiveté…these animals aren’t imbeciles. Evolution has merely prepared them for a life in a world that is simpler and more innocent”…. where humans are entirely outside their experience. David Quammen (Island Biography in an age of extinction) 1996 1 ABSTRACT The Falkland Islands are globally important for the Striated Caracaras (Phalcoboenus australis). They reside mainly on the outer islands of the archipelago in strong associated with seabird populations, and where human interference is relatively low. A survey of the breeding population conducted in the austral summers of 2013/2014 and 2014/2015 indicates that the current population is likely to be the highest it has been for perhaps the last 100 years. -

Freshwater Fish in the Falklands

Freshwater fish in the Falklands Conservation of native zebra trout Echo Goodwin, North Arm School A report by Katherine Ross to the Falkland Islands Government and Falklands Conservation, 2009. Summary • Only two species of freshwater fish, Zebra trout (Aplochiton zebra) and Falklands minnows (Galaxias maculatus) are native to the Falklands. • Brown trout (Salmo trutta) were introduced to the Falklands in the 1940’s and 1950’s. They can spend part of their life cycle at sea which has allowed them to spread across the islands causing a catastrophic decline in the distribution of zebra trout. The ways by which brown trout remove zebra trout probably include predation on juvenile fish and competition for food. • Zebra trout are long lived and therefore adult populations may persist for many years where juveniles no longer survive. Such populations can become extinct suddenly. • Freshwater fish of the Falklands were last surveyed in 1999. • This project investigated the distribution of freshwater fish in West and East Falkland by electrofishing, netting and visual surveys and identified conservation priorities for zebra trout. • Zebra trout populations were found in Lafonia, the south of West Falkland and Port Howard. Brown trout were found across much of Lafonia where their range appears to have expanded since 1999. • Once brown trout have invaded a catchment they are very difficult to remove. Controlling the spread of brown trout is therefore an urgent priority if zebra trout are to be conserved. • Freshwater habitats where zebra trout were found were generally in good condition but in some areas perched culverts may prevent juvenile zebra trout from returning to freshwaters (we think larval zebra trout spend their first few months at sea). -

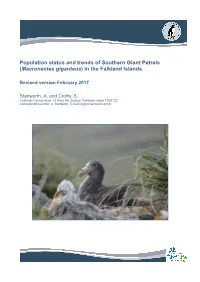

Population Status and Trends of Southern Giant Petrels (Macronectes Giganteus ) in the Falkland Islands

Population status and trends of Southern Giant Petrels (Macronectes giganteus ) in the Falkland Islands Revised version February 2017 Stanworth, A. and Crofts, S. Falklands Conservation, 41 Ross Rd, Stanley, Falkland Islands FIQQ1ZZ Corresponding Author: A. Stanworth. E-mail:[email protected] Acknowledgements We thank the British Forces South Atlantic Islands and Ministry of Defence for provision of aerial site photographs. We are very grateful to all those who provided counts, gave information on colony locations, helpful discussion regarding the survey approaches and shared their observations of the species. The work was supported by Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Citation: Stanworth, A. and Crofts, S. (2017). Population status and trends of Southern Giant Petrels ( Macronectes giganteus ) in the Falkland Islands. Falklands Conservation. Summary A survey of key breeding sites of Southern Giant Petrels (Macronectes giganteus ) within the Falkland Islands was undertaken in 2015/16. The minimum breeding population of the Islands was estimated to be 20,970 ± 180 pairs, an increase of 7.4 % since the previous census in 2004/05. Sixteen breeding sites were confirmed, supporting a minimum of 21 colonies/ breeding areas; however, this figure does not account for likely additional small groups or single pairs breeding around the coasts, which were not surveyed. Based on the previous census, these small groups (constituting less than 0.5 % of the total estimated figure in 2004/05) are unlikely to significantly influence the overall population estimate. The current Falkland estimate would increase the global population estimate by 1441 breeding pairs to 48,239 breeding pairs; of which the Falklands would comprise approximately 43 %. -

PATTERSON James and Esther.Pdf

PATTERSON FAMILY VERSION: 22 September 2015 PATTERSON FAMILY NB: The following is prepared from Falkland Islands Registers and files – there may be other family born outside the Falklands. Unless stated otherwise, all dated births, deaths and marriages occurred in the Falklands and all numbered graves are in Stanley Cemetery. Any variations which may occur in the spellings of names are recorded as written in the records at the time. James PATTERSON was married to Esther HOPE 4 January 1819 in Applegarth, Dumfries, Scotland. Esther died in 1881. Esther was born in 1797 in Applegarth, Dumfries, Scotland. Children of James and Esther PATTERSON: 1. Mary PATTERSON born 15 March 1819 in Applegarth, Dumfries, Scotland 2. Margaret PATTERSON born 20 June 1821. Margaret was married to Thomas DOBIE 21 December 1851 in Applegarth, Dumfries, Scotland. Thomas was born 22 January 1820 in Applegarth, Dumfries, Scotland. 3. James PATTERSON born 19 December 1823 in Hutton & Corrie, Dumfries, Scotland. Died young? 4. Thomas PATTERSON born 17 May 1826 in Hutton & Corrie, Dumfries, Scotland. Died young? 5. Janet PATTERSON born 12 March 1829 in Hutton & Corrie, Dumfries, Scotland. Died young? 6. James PATTERSON born in 1830 in Hutton & Corrie, Dumfries, Scotland. 7. Thomas Hope PATTERSON born 28 January 1834 in Hutton & Corrie, Kirkmichael, Dumfries, Scotland. Thomas was married to Agnes CLARKE 11 July 1862 in Garrel Hill, Kirkmichael, Dumfries, Scotland. Thomas, age 36 and a shepherd, Agnes, age 32, Robert, age 6, William, age 4, and George, age 1 left London, 11 October 1872 on board the brig Francis, arriving in Stanley 7 January 1873. -

International Tours & Travel the Falkland Islands Travel Specialists

Welcome to the Falkland Islands The Falkland Islands Travel Specialists International Tours & Travel www.falklandislands.travel FALKLAND ISLANDS Grand Steeple 1186 Jason Jason 779 Pebble Is. Marble Mt 909 Cape Dolphin First Mt 723 Carcass Is. THE ROOKERY THE NECK 1384 Kepple Is. Rookery Mt Elephant Saunders Is. Beach Farm West Point Is. 1211 Salvador Cli Mt Coutts Hill Douglas 926 Dunbar 751 Salvador Hill Johnson’s 1709 Mt Rosalie Port Station Volunteer Byron Heights Shallow 1396 San Carlos Harbour Mt D’Arcy Point Bay Bombilla Hill Hill Cove 1370 938 er S 648 v RACE POINT a Ri arrah n Port Louis W FARM C a r l o s Roy Cove R BERKLEY SOUND San Carlos i v e Teal Inlet Port r WEST FALKLAND KINGSFORD Long Island 2297 Howard VALLEY FARM Malo Hill 658 Crooked Mt Adam Mt Maria 871 KING 2158 River Mt Low Inlet Muer Jack Mt Marlo Murrell Passage Is. GEORGE 1796 Mt Kent Mt Longdon BAY D 1504 Smoko Mt Two Sisters Cape 2312 1392 Mt Tumbledown N Mt William Pembroke Chartres Saladero Mt Usborne Mt Wickham U 2056 Stanley O Blu Mt Moody Fitzroy River Dunnose Head 1816 S New Haven Mount Pleasant Cove New Is. Little Airport Fitzroy Chartres Darwin Mt Sulivan Spring Point 1554 Goose QUEEN D Lake Green Bertha’s CHARLOTTE Sulivan N Beach Beaver Is. BAY A LAFONIA CHOISEUL SOUND Weddell Is. L EAST FALKLAND 1256 Fox Bay (E) K Mt Weddell Fox Bay (W) Walker South L Harbour Creek A Lively Is. Port Edgar F Mt Emery Mt Young 1164 1115 North Port Arm Mt Alice Stephens 1185 Speedwell Is. -

Census of the Southern Giant Petrel Population of the Falkland Islands 2004/2005

Bird Conservation International (2008) 18:118–128. ß BirdLife International 2008 doi: 10.1017/S0959270908000105 Printed in the United Kingdom Census of the Southern Giant Petrel population of the Falkland Islands 2004/2005 TIM A. REID and NIC HUIN Summary A complete census was taken of all colonies of Southern Giant Petrels Macronectes giganteus within the Falkland Islands in 2004/05. The breeding population of the islands was estimated to be approximately 19,529 pairs (range 18,420–20,377). Southern Giant Petrels were found to breed in 38 locations around the islands, with colony size varying from one to 10,936. The majority of colonies were concentrated around the south of Falkland Sound, and to the west of West Falkland. Whilst there has been no previous census of the total population of the islands, there is a strong indication that the population has increased since the 1950s. The reasons for such an increase in population remain unclear in light of current knowledge. Development of our understanding of the breeding biology and demography of this species in the Falkland Islands is necessary, as is the need to conduct such a census every five years, with a few key colonies to be monitored every season. From the results obtained here, the conservation status of the Southern Giant Petrel, currently listed as ‘Vulnerable’, could be downgraded to ‘Near Threatened’. Introduction Concerns have been raised over the conservation status of many species of albatross and petrels throughout the world. These concerns derive from observations of significant numbers of these seabirds being killed in longline (e.g. -

Explore Untrammeled Islands on Our 1St-Ever Circumnavigation: Linger Longer Amid Wildlife & Glorious Landscapes

FALKLANDS 360˚ EXPLORE UNTRAMMELED ISLANDS ON OUR 1ST-EVER CIRCUMNAVIGATION: LINGER LONGER AMID WILDLIFE & GLORIOUS LANDSCAPES ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ORION | 2016 TM DEAR TRAVELER, It was in February 1976, after a long, long voyage from New Zealand to the Ross Sea to the Antarctic Peninsula that I first set eyes on the Falkland Islands. Nearly a month of ice and sea suddenly gave way to verdant greens and even wildflowers. We languished in the tussock grass amid the greatest concentrations of sea birds I had ever seen—black-browed albatross (there are over 150,000 breeding pairs here), plus penguins— rockhopper and Magellanic—sea lions, elephant seals, and more. And that’s not all: a hearty, hospitable people with British roots live here. And, at times, we were invited into homes for ‘afternoon tea.’ All of us were delighted by the benign beauty and relative calm of this place while, at the same time, it teemed with nature in myriad forms. It’s not surprising that many have referred to the Falklands archipelago as the ‘Galápagos of the South.’ We were only there for 3 days, and none of us wanted to leave. And I’ve wanted to offer a focused Falklands itinerary ever since, but hesitated because people kept saying that there won’t be demand—so close to Antarctica without going there. But now, 40 years later, I’m convinced this is pure ‘balderdash.’ The more you know about the Falklands, the more you will be convinced that it’s worth the singular focus. So, we’re delighted to offer our 1st-ever circumnavigation of these most remarkable islands. -

Falkland Islands Gazette, 1911

INDEX TO Falkland Islands Gazette, 1911. Page. Page. Accounts—(Statements) Address from Citizens of Stanley on Their Majesties Coronation 160 Currency Note Fund 19. 61, 86. 108, 121. 131, 143. 152, 162 Atkins. W., Leave of absence 60 Summary of Ledger Balances 2. 25, 74, 75. 83, 106, 120 Auction, Sale of Town Land 127 130, 141, 151, 158, 200 Assets and Liabilities ... 63, 72 Beacon, William Point, Notice to Manners 24 Revenue ami Expenditure 50, 88, 128, 160 Belgium, Extradition Treaty with 156 .. Estimated surplus of Assets, 31st December 159 Appointments— Bills- Government Wharfs 36 Aldridge, John, Member of Board of Health, E.F. 23 Legislative Council, to validate certain proceedings of 119 Baseley, R B., Chief Engineer Fire Brigade ... 82 Ordinances of the Colony, new editions of 203 Biggs, V A. H.— Probate Amendment Ordinance ... 77 Member of Board of Health, E.F. 23 Boards of Health 23 Hon. Secretary Fire Brigade S2 Brand—Mr. S. Kirwan 122 Birch, Capt A. G., Superintendent Fire Brigade SI Building Byo-laws, amendment of 125 Boilean, Lewis II.— Temp. Clerk to Executive Council 22 Temp. Clerk to Legislative Council 195 Census. 1911, Notice ... 5 Brown, J. W.— Coins, New design for 43, 61 Temp. Deputy Postmaster & Deputy Collisions at sea 33, 113 Collector of Customs at Fox Bay 99 Commissioners to administer oaths, rules of Court as to 198 deceiver of Goose Beaks 157 Commissioners of Currency— Bowne, W. M.-- Auditor’s Report for 1910 61 Asst. Colonial Surgeon, E.F. 135 Statement of Assets k Liabilities, 1910 63 Justice of the Peace ..