ICAA Documents Project Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guía Del Patrimonio Cultural De Buenos Aires

01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 2 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 1 1 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 2 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 3 1 > EDIFICIOS > SITIOS > PAISAJES 01-014 inicio.qxp 21/10/2008 13:11 PÆgina 4 Guía del patrimonio cultural de Buenos Aires 1 : edificios, sitios y paisajes. - 1a ed. - Buenos Aires : Dirección General Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico, 2008. 280 p. : il. ; 23x12 cm. ISBN 978-987-24434-3-6 1. Patrimonio Cultural. CDD 363.69 Fecha de catalogación: 26/08/2008 © 2003 - 1ª ed. Dirección General de Patrimonio © 2005 - 2ª ed. Dirección General de Patrimonio ISBN 978-987-24434-3-6 © 2008 Dirección General Patrimonio e Instituto Histórico Avda. Córdoba 1556, 1º piso (1055) Buenos Aires, Argentina Tel. 54 11 4813-9370 / 5822 Correo electrónico: [email protected] Dirección editorial Liliana Barela Supervisión de la edición Lidia González Revisión de textos Néstor Zakim Edición Rosa De Luca Marcela Barsamian Corrección Paula Álvarez Arbelais Fernando Salvati Diseño editorial Silvia Troian Dominique Cortondo Marcelo Bukavec Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723. Libro de edición argentina. Impreso en la Argentina. No se permite la reproducción total o parcial, el almacenamiento, el alquiler, la transmisión o la transformación de este libro, en cualquier forma o por cualquier medio, sea electrónico o mecánico, mediante fotocopias, digitalización u otros métodos, sin el permiso previo y escrito del editor. Su infrac- ción está penada por las leyes 11.723 y 25.446. -

Review/Reseña Arte Argentino En Los Años Sesenta Viviana Usubiaga

Vol. 7, No. 2, Winter 2010, 433-439 www.ncsu.edu/project/acontracorriente Review/Reseña Andrea Giunta, Avant-Garde, Internationalism, and Politics. Argentine Art in the Sixties. Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2007. Arte argentino en los años sesenta Viviana Usubiaga Universidad de Buenos Aires/CONICET Los años sesenta han originado múltiples reflexiones y análisis desde diversos abordajes, muchos de ellos basados en el potencial de transformaciones sociales experimentadas en el mundo agitado de aquella década. En efecto, los ’60 se han convertido en un objeto de estudio que seduce por su carácter mítico, construido menos sobre una época de logros concretos que sobre el caudal de ilusiones que despertó y estimuló. Varios fueron los hitos en el orden político, económico y cultural que definieron aquellos años como un punto de inflexión en la historia del Usubiaga 434 siglo XX. Entre otros, diferentes movimientos sociales cuestionaron y pusieron en crisis los sistemas de macro y micro poder establecidos hasta entonces; la Guerra Fría comenzó a entibiarse con nuevos frentes bélicos y el desarrollo de los procesos de descolonización. En América Latina en particular, las repercusiones de la Revolución Cubana despertaron esperanzas de cambio y generaron expectativas sobre un futuro más favorable para sus poblaciones. Como contrapartida, Estados Unidos renovó sus esfuerzos para neutralizar y contrarrestar la influencia de la experiencia cubana entre los intelectuales latinoamericanos. El programa de la Alianza para el Progreso fue su instrumento. Es en este escenario donde Andrea Giunta se instala para analizar el caso Argentino y propone interrogar productivamente la dinámica del campo artístico durante los años sesenta. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

La Última Dictadura, Los Usos Del Pasado Y La Construcción De Narrativas Autolegitimantes (Buenos Aires, 1979-1980)

Quinto Sol ISSN: 0329-2665 ISSN: 1851-2879 [email protected] Universidad Nacional de La Pampa Argentina Monumentos, marcas y homenajes: la última dictadura, los usos del pasado y la construcción de narrativas autolegitimantes (Buenos Aires, 1979-1980) Schenquer, Laura; Cañada, Lucía Monumentos, marcas y homenajes: la última dictadura, los usos del pasado y la construcción de narrativas autolegitimantes (Buenos Aires, 1979-1980) Quinto Sol, vol. 24, núm. 2, 2020 Universidad Nacional de La Pampa, Argentina Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=23163487005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.19137/qs.v24i2.3797 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional. PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Laura Schenquer, et al. Monumentos, marcas y homenajes: la última dictadura, los usos del pasado ... Artículos Monumentos, marcas y homenajes: la última dictadura, los usos del pasado y la construcción de narrativas autolegitimantes (Buenos Aires, 1979-1980) Monuments, marks and tributes: the last dictatorship, the uses of the past and the construction of self-legitimating narratives (Buenos Aires, 1979-1980) Monumentos, marcas e homenagens: a última ditadura, os usos do passado e a construção de narrativas autolegitimáveis (Buenos Aires, 1979-1980) Laura Schenquer DOI: https://doi.org/10.19137/qs.v24i2.3797 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? Argentina id=23163487005 Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Argentina [email protected] Lucía Cañada Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina [email protected] Recepción: 15 Abril 2019 Aprobación: 02 Julio 2019 Resumen: La pregunta por el control represivo y por la conquista del consenso social viene inquietando a los estudiosos de los regímenes fascistas y autoritarios. -

The Emergent Decade : Latin American Painters and Painting In

a? - H , Latin American Painters and Painting in trie 1'960's THE - -y /- ENT Text by Thomas M. Messer Artjsts' profiles in text and pictures by Cornell Capa DEC THE EMERGENT DECADE THE EMERGENT DECADE Latin American Painters and Painting in the 1960's Text by Thomas M. Messer Artists' profiles in text and pictures by Cornell Capa Prepared under the auspices of the Cornell University Latin American Year 1965-1966 and The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum > All rights reserved First published 1966 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 66-15382 Design by Kathleen Haven Printed in Switzerland bv Buchdruckerei Winterthur AG, Winterthur CONTENTS All text, except where otherwise indicated, is by Thomas M. Messer, and all profiles are by Cornell Capa. Foreword by William H. MacLeish ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction xm Brazil Correspondence: Thomas M. Messer and Marc Berkowitz 3 Primitive Art 16 Profile: Raimundo de Oliveira 18 Uruguay Uruguayan Painting 29 Argentina Correspondence: Thomas M. Messer and Samuel Paz 35 Profile: Rogelio Polesello and Martha Peluffo 48 Expatriates: New York 59 Profile: Jose Antonio Fernandez-Muro 62 Chile Profile: Ricardo Yrarrazaval 74 Correspondence: Thomas M. Messer and Jorge Elliott 81 Peru Correspondence: Thomas M. Messer and Carlos Rodriguez Saavedra 88 Profile: Fernando de Szyszlo 92 Colombia Correspondence: Thomas M. Messer to Marta Traba 102 Profile: Alejandro Obregon 104 Correspondence: Marta Traba to Thomas M. Messer 1 14 Venezuela Biographical Note: Armando Reveron 122 Living in Painting: Venezuelan Art Today by Clara Diament de Sujo 124 Correspondence: Thomas M. Messer to Clara Diament de Sujo 126 Expatriates: Paris 135 Profile: Soto 136 Mexico Profile: Rufino Tamayo 146 Correspondence: Thomas M. -

Guia Del Participante

“STRENGTHENING THE TUBERCULOSIS LABORATORY NETWORK IN THE AMERICAS REGION” PROGRAM PARTICIPANT GUIDELINE The Andean Health Organization - Hipolito Unanue Agreement within the framework of the Program “Strengthening the Network of Tuberculosis Laboratories in the Region of the Americas”, gives you the warmest welcome to Buenos Aires - Argentina, wishing you a pleasant stay. Below, we provide information about the city and logistics of the meetings: III REGIONAL TECHNICAL MEETING OF TUBERCULOSIS LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE WORKSHOP II FOLLOW-UP MEETING Countries of South America and Cuba Buenos Aires, Argentina September 4 and 5, 2019 VENUE Lounge Hidalgo of El Conquistador Hotel. Direction: Suipacha 948 (C1008AAT) – Buenos Aires – Argentina Phones: + (54-11) 4328-3012 Web: www.elconquistador.com.ar/ LODGING Single rooms have been reserved at The Conquistador Hotel Each room has a private bathroom, heating, WiFi, 32” LCD TV with cable system, clock radio, hairdryer. The room costs will be paid directly by the ORAS - CONHU / TB Program - FM. IMPORTANT: The participant must present when registering at the Hotel, their Passport duly sealed their entry to Argentina. TRANSPORTATION Participants are advised to use accredited taxis at the airport for their transfer to The Conquistador hotel, and vice versa. The ORAS / CONHU TB - FM Program will accredit in its per diems a fixed additional value for the concept of mobility (airport - hotel - airport). Guideline Participant Page 1 “STRENGTHENING THE TUBERCULOSIS LABORATORY NETWORK IN THE AMERICAS REGION” PROGRAM TICKETS AND PER DIEM The TB - FM Program will provide airfare and accommodation, which will be sent via email from our office. The per diem assigned for their participation are Ad Hoc and will be delivered on the first day of the meeting, along with a fixed cost for the airport - hotel - airport mobility. -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

Plano Portugués

R ío Limay Spika Gonçalves Días Perdriel Luzuriaga Sánchez de Loria Renacimiento Gral. Urquiza P. Chutro Labarden 2700 Los Patos Santo Domingo Luna 1800 Sta. María del BuenCalifornia Ayre 800 Uspallata Senillosa Lavadero Santa Elena Bardi Manuel García Inclán Spegazzini Meana Tarija Av. La Plata Av. Acoyte Darquier ESTACIÓN Pavón Muñiz PLAZA Río Cuarto Cotagaita 1600 1000 Campichuelo Ambrosetti Herrera BUENOS AIRES La Rioja Apule Cochabamba DÍAZ VÉLEZ Lafayette 100 Av. Chiclana Olavarría 2700 3200 Danel México A. de Lamadrid Av. Colonia América C. Castillo F. Devoto Monasterio 24 de Noviembre 3600 Toll 800 4000 San Ricardo Esquel Av. Iriarte Salom Luzuriaga 2400 2200 Av. CaserosCatamarca BOEDO Estados Unidos Jorge Gonçalves Días Cooperación E. Lobos 4800 Donado Mutualismo Deán Funes Quito J. Mármol Yerbal 800 Del Parque 2100 Casacuberta 2200 Montenegro Treinta y tres Orientales Tres Arroyos 3200 Villarino Sta. Magdalena Constitución Otamendi Alvarado RÍO DE Galicia 13 300 E. de San Martin Olaya 300 500 Av. Jujuy Franklin Luis Viale 1100 2800 1300 Castro Agrelo Gral. Venancio Flores Huaura S 100 San Ignacio JANEIRO Dr. F. Aranguren Dr. Luis Beláustegui 1400 Patagones 3800 4900 u 2800 Huemul Hidalgo s Girardot San Antonio Quintino Bocayuva Bogotá Ferrari Av. Warnes900 in Girardot Girardot Osvaldo Cruz Río de Janeiro i 2200 Australia 2800 4400 A. Machado 1300 Av. Hipólito Vieytes 2900 Portugal 1100 Martínez Rosas CEMENTERIO 3700 3300 4000 4900 Miravé 4200 600 ALEMÁN Prudan 1600 Santa Cruz 4600 2700 2400 Oruro Yapeyú 700 700 Caldas PARQUE Salcedo Cnel. Apolinario FIgueroa Río Cuarto Rondeau J. J. Pérez L. Marechal Caldas Pacheco Matheu 3000 Dumont S. -

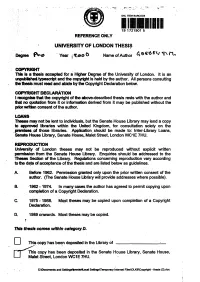

This Thesis Comes Within Category D

* SHL ITEM BARCODE 19 1721901 5 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year i ^Loo 0 Name of Author COPYRIGHT This Is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, it is an unpubfished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the .premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 -1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 -1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Chile & Argentina

Congregation Etz Chayim of Palo Alto CHILE & ARGENTINA Santiago - Valparaíso - Viña del Mar - Puerto Varas - Chiloé - Bariloche - Buenos Aires November 3-14, 2021 Buenos Aires Viña del Mar Iguazú Falls Post-extension November 14-17, 2021 Devil’s throat at Iguazu Falls Join Rabbi Chaim Koritzinsky for an unforgettable trip! 5/21/2020 Tuesday November 2 DEPARTURE Depart San Francisco on overnight flights to Santiago. Wednesday November 3 SANTIGO, CHILE (D) Arrive in Santiago in the morning. This afternoon visit the Plaza de Armas, Palacio de la Moneda, site of the presidential office. At the end of the day take the funicular to the top of Cerro San Cristobal for a panoramic view of the city followed by a visit to the Bomba Israel, a firefighter’s station operated by members of the Jewish Community. Enjoy a welcome dinner at Restaurant Giratorio. Overnight: Hotel Novotel Providencia View from Cerro San Cristóbal - Santiago Thursday November 4 VALPARAÍSO & VIÑA del MAR (B, L) Drive one hour to Valparaíso. Founded in 1536 and declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003, Valparaíso is Chile’s most important port. Ride some of the city’s hundred-year-old funiculars that connect the port to the upper city and visit Pablo Neruda’s home, “La Sebastiana”. Enjoy lunch at Chez Gerald continue to the neighboring city of. The “Garden City” was founded in 1878 and is so called for its flower-lined avenues. Stroll along the city’s fashionable promenade and visit the Wulff Castle, an iconic building constructed in neo-Tudor style in 1906. -

ARTIST - LEÓN FERRARI Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1920 Died in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2013

ARTIST - LEÓN FERRARI Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1920 Died in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2013 EDUCATION - 1938-1947 : Engeneering at the University of Buenos Aires, Argentina SOLO SHOWS (SELECTION) - 2018 Galerie Mitterrand, Paris, France Pérez Art Museum, Miami, FL, USA Galeria Nara Roesler, Sao Paulo, Brazil 2017 REDCAT, Los Angeles, CA, USA 2015 Sicardi Gallery, Houston, TX, USA 2014 Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires (MAMBA), Buenos Aires, Argentina 2012 Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), Buenos Aires, Argentina 2011 Haunch of Venison, New York, NY, USA Museo del Banco de la República de Bogotá, Colombia 2010 Église Sainte Anne, Arles, France Fondo Nacional de las Artes, Buenos Aires, Argentina Museo Emilio Caraffa, Córdoba, Argentina Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes Juan B. Castagnino Museo de Arte Contemporaneo, Rosario, Argentina Secundario de Artes, Fiorito, Buenos Aires, Argentina Museo de Bellas Artes, Salta, Argentina 2009 Sicardi Gallery, Houston, TX, USA Galería Zavaleta LAB, Buenos Aires, Argentina Universidad Nacional del Litoral, Santa Fe, Argentina 2008 Galería Braga Menéndez Arte Contemporáneo, Buenos Aires, Argentina Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, Mexico City, Mexico Museo Municipal de Bellas Artes Juan B. Castagnino, Ciudad de Rosario, Argentina 2007 Secretaría de Cultura de la Nación, Buenos Aires, Argentina Galería Ruth Benzacar, Buenos Aires, Argentina 79 RUE DU TEMPLE 75003 PARIS - T +33 (0)1 43 26 12 05 F +33 (0)1 46 33 44 83 [email protected] WWW.GALERIEMITTERRAND.COM 2006 -

Issue No. 57 | October 2011 the Official Journal of the Kamra Tal-Periti

ISSUE NO. 57 | OCTOBER 2011 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE KAMRA TAL-PERITI OST P NEWSPAPER NEWSPAPER contents 12 15 PRACTICE 04 4 EDITORIAL 5 KTP NEWS 06 6-9 PEOPLE & PROJECTS 10 EU DESK 11 SACES FEATURE 12 12-13 JAPANESE GARDEN 14-16 MALTA DESIGN WEEK 16-18 HOUSING 19 FE ANALYSIS 20 curreNT 20 20 EASA 21 HERITAGE 22 WEB + COMPETITION 23 INTERNATIONAL EVENTS 19 “Architecture is understood to go beyond the physical development of our built environment and considered a cultural reference to sustainable development.” National Cultural Policy, Malta, 2011 See Editorial for details OCTOBER 2011 THE ARCHItect 3 THE PROFESSIONAL CENTRE Summer is a peculiar season … I welcome the late Policy Actions presented in this document. SLIEMA ROAD sunsets, the cool evenings by the seaside, the open GZIRA GZR 06 - MALTA air events that pepper the Maltese calendar at this The draft National Environment Policy builds further TEL./FAX. (+356) 2131 4265 time … yet I dread the long hot days, the drone of my on the above. It speaks about Government’s commit- EMAIL: [email protected] EDITORIAL desk fan, the constant feeling that it will never be over. ment to continue to protect Malta’s built heritage and WEBSITE: www.ktpmalta.com Despite this, the summer of 2011 brought with it two to improve the environment in historic areas. It further very welcome breaths of fresh air - the publication of identifies the need to “improve the liveability of urban To support members of the profession in achieving excellence in their the National Cultural Policy in July and the