Intensified Foraging and the Roots of Farming in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fenhe (Fen He)

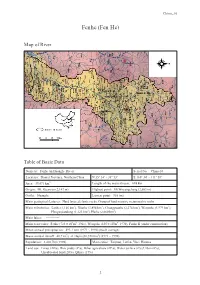

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

旅游减贫案例2020(2021-04-06)

1 2020 世界旅游联盟旅游减贫案例 WTA Best Practice in Poverty Alleviation Through Tourism 2020 Contents 目录 广西河池市巴马瑶族自治县:充分发挥生态优势,打造特色旅游扶贫 Bama Yao Autonomous County, Hechi City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region: Give Full Play to Ecological Dominance and Create Featured Tour for Poverty Alleviation / 002 世界银行约旦遗产投资项目:促进城市与文化遗产旅游的协同发展 World Bank Heritage Investment Project in Jordan: Promote Coordinated Development of Urban and Cultural Heritage Tourism / 017 山东临沂市兰陵县压油沟村:“企业 + 政府 + 合作社 + 农户”的组合模式 Yayougou Village, Lanling County, Linyi City, Shandong Province: A Combination Mode of “Enterprise + Government + Cooperative + Peasant Household” / 030 江西井冈山市茅坪镇神山村:多项扶贫措施相辅相成,让山区变成景区 Shenshan Village, Maoping Town, Jinggangshan City, Jiangxi Province: Complementary Help-the-poor Measures Turn the Mountainous Area into a Scenic Spot / 038 中山大学: 旅游脱贫的“阿者科计划” Sun Yat-sen University: Tourism-based Poverty Alleviation Project “Azheke Plan” / 046 爱彼迎:用“爱彼迎学院模式”助推南非减贫 Airbnb: Promote Poverty Reduction in South Africa with the “Airbnb Academy Model” / 056 “三区三州”旅游大环线宣传推广联盟:用大 IP 开创地区文化旅游扶贫的新模式 Promotion Alliance for “A Priority in the National Poverty Alleviation Strategy” Circular Tour: Utilize Important IP to Create a New Model of Poverty Alleviation through Cultural Tourism / 064 山西晋中市左权县:全域旅游走活“扶贫一盘棋” Zuoquan County, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province: Alleviating Poverty through All-for-one Tourism / 072 中国旅行社协会铁道旅游分会:利用专列优势,实现“精准扶贫” Railway Tourism Branch of China Association of Travel Services: Realizing “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” Utilizing the Advantage -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 341 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019) Field Investigation on Eight Tones in Matang Village, Renhua County* Qunying Wang Xiaoyan Chen School of Music School of Music Shaoguan University Shaoguan University Shaoguan, China 512005 Shaoguan, China 512005 Abstract—The Eight-tone Band (also called Matang Drum the above Guangdong folk art forms. It is the "eight-tone Band) of Matang village, Renhua county in Shaoguan city, troupe". The so-called eight-tone music originally refers to Guangdong province is an active local eight-tone club. It has the classification name of ancient Musical Instruments. Here been providing the villagers with performance for happy it refers to a folk music activity, a pure instrumental form. occasions and funeral affairs since the 60s except during the The term "eight tones" first appeared in the Zhou Dynasty. Cultural Revolution. Their music can be divided to music for At that time, instruments were divided into eight categories happy occasions and for funeral affairs, the former being according to the different materials, namely "metal, stone, joyous and cheerful and the latter sad and low-pitched. But clay, leather, silk, wood, gourd, bamboo". Later, it was with the development of the society, the Eight-tone Band is also widely used to refer to musical instruments. Now the changing. generally referred "eight-tone troupe" refers to a kind of rural Keywords—the Eight-tone Band; pattern of manifestation; folk music (including blowing, playing, drumming, singing), music characteristics; status quo of inheritance and "eight-tone music" is the music played by the eight-tone troupes. -

SARS CHINA Case Distribution by Prefecture-20 May 20031

Source: Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China SARS Case Distribution by Prefecture(City) in China (Accessed 10:00 20 May 2003) No. Area Prefecture Cumulati Level of local Last Remarks (city) ve transmission reported Probable date Cases 1 Beijing 2444 C 20-May 2 Tianjin 175 C 17-May 3 Hebei 217 Shijiazhuang 24 B 20-May Baoding 31 B 18-May Qinhuangdao 5 UNCERTAIN 7-May Langfang 17 A 14-May Cangzhou 1 NO 26-Apr Tangshan 50 B 18-May Chengde 12 A 20-May Zhangjiakou 66 A 16-May Handan 6 NO 18-May Hengshui 1 NO 7-May Xingtai 4 NO 19-May 4 Shanxi 445 Changzhi 4 NO 8-May Datong 5 NO 8-May Jincheng 1 NO 4-May Jinzhong 49 B 15-May Linfen 18 B 4-May Lvliang 2 NO 13-May Shuozhou 4 NO 17-May Taiyuan 338 C 20-May Xinzhou 4 NO 8-May Yangquan 8 A 10-May Yuncheng 12 A 15-May 5 Inner 287 Mongolia Huhehot 148 C 20-May Baotou 14 B 10-May Bayanzhouer 102 C 15-May 1 Wulanchabu 9 B 6-May Tongliao 1 NO 26-May Xilinguole 10 B 17-May Chifeng 3 NO 6-May 6 Liaoning 3 Huludao 1 NO 26-Apr Liaoyang 1 NO 8-May Dalian 1 NO 12-May 7 Jilin 35 Changchun 34 B 17-May Jilin 1 NO 26-May 8 Heilongjiang 0 9 Shanghai 7 NO 10-May 10 Jiangsu 7 Yancheng 1 NO 2-May Xuzhou 1 NO Before 26 April Nantong 1 NO 30-Apr Huai’an 1 NO 2-May Nanjing 2 A 11-May 1st case of local transmission reported on May 10 Suqian 1 NO 8-May 11 Zhejiang 4 Hangzhou 4 NO 8-May 12 Anhui 10 Fuyang 6 NO 2-May Hefei 1 NO 30-Apr Bengbu 2 NO 10-May Anqing 1 NO 5-May 13 Fujian 3 Sanming 1 NO Before 26 April Xiamen 2 NO Before 26 April 14 Jiangxi 1 Ji’an 1 NO 4-May 15 Shandong 1 2 Jinan 1 NO 22-Apr 16 Henan -

Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia Were Not the Descendants of Yan Huang

E-Leader Brno 2019 Originally, the Descendants of Hua Xia were not the Descendants of Yan Huang Soleilmavis Liu, Activist Peacepink, Yantai, Shandong, China Many Chinese people claimed that they are descendants of Yan Huang, while claiming that they are descendants of Hua Xia. (Yan refers to Yan Di, Huang refers to Huang Di and Xia refers to the Xia Dynasty). Are these true or false? We will find out from Shanhaijing ’s records and modern archaeological discoveries. Abstract Shanhaijing (Classic of Mountains and Seas ) records many ancient groups of people in Neolithic China. The five biggest were: Yan Di, Huang Di, Zhuan Xu, Di Jun and Shao Hao. These were not only the names of groups, but also the names of individuals, who were regarded by many groups as common male ancestors. These groups first lived in the Pamirs Plateau, soon gathered in the north of the Tibetan Plateau and west of the Qinghai Lake and learned from each other advanced sciences and technologies, later spread out to other places of China and built their unique ancient cultures during the Neolithic Age. The Yan Di’s offspring spread out to the west of the Taklamakan Desert;The Huang Di’s offspring spread out to the north of the Chishui River, Tianshan Mountains and further northern and northeastern areas;The Di Jun’s and Shao Hao’s offspring spread out to the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, where the Di Jun’s offspring lived in the west of the Shao Hao’s territories, which were near the sea or in the Shandong Peninsula.Modern archaeological discoveries have revealed the authenticity of Shanhaijing ’s records. -

The Spatial Differentiation of the Suitability of Ice-Snow Tourist Destinations Based on a Comprehensive Evaluation Model in China

sustainability Article The Spatial Differentiation of the Suitability of Ice-Snow Tourist Destinations Based on a Comprehensive Evaluation Model in China Jun Yang 1,*, Ruimeng Yang 1, Jing Sun 1, Tai Huang 2,3,* and Quansheng Ge 3 1 Liaoning Key Laboratory of Physical Geography and Geomatics, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian 116029, China; [email protected] (R.Y.); [email protected] (J.S.) 2 Department of Tourism Management, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, China 3 Key Laboratory of Land Surface Patterns and Simulation, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (T.H.) Academic Editors: Jun Liu, Gang Liu and This Rutishauser Received: 1 February 2017; Accepted: 4 May 2017; Published: 8 May 2017 Abstract: Ice, snow, and rime are wonders of the cold season in an alpine climate zone and climate landscape. With its pure, spectacular, and magical features, these regions attract numerous tourists. Ice and snow landscapes can provide not only visually-stimulating experiences for people, but also opportunities for outdoor play and movement. In China, ice and snow tourism is a new type of recreation; however, the establishment of snow and ice in relation to the suitability of the surrounding has not been clearly expressed. Based on multi-source data, such as tourism, weather, and traffic data, this paper employs the Delphi-analytic hierarchy process (AHP) evaluation method and a spatial analysis method to study the spatial differences of snow and ice tourism suitability in China. China’s ice and snow tourism is located in the latitude from 35◦N to 53.33◦N and latitude 41.5◦N to 45◦N and longitude 82◦E to 90◦E, with the main focus on latitude and terrain factors. -

Due to the Special Circumstances of China Nancy L

Bridgewater Review Volume 5 | Issue 2 Article 6 Nov-1987 Due to the Special Circumstances of China Nancy L. Street Bridgewater State College, [email protected] Recommended Citation Street, Nancy L. (1987). Due to the Special Circumstances of China. Bridgewater Review, 5(2), 7-10. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol5/iss2/6 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. --------------ES SAY-------------- Due To The Special Circumstances ofCHIN1\... BY NANCY LYNCH STREET ,~d Ifim 'h, ,boY< 'id, in 'h, <xch'nge pmgrnm 'On"''' "'''",n Shanxi Teacher's University and Bridgewater State College. I pondered it for awhile, then dropped it. I would find out soon enough the "special circumstances of China." First, I had to get ready to go to China. Ultimately, the context of the phrase would enlighten me. During the academic year 1985-1986 I taught at Shanxi Teacher's University which is located in Linfen, Shanxi Province, People's Republic of China. Like the Chinese, I would soon learn the virtues of quietness and patience. I would listen and look and remember. Perhaps most important of all, I would make friends whom I shall never forget. FROM BE]ING TO LINFEN Cultural Revolution. Seventeen hours by from personal observations here and The Setting train north to Beijing, eight hours south abroad; and finally, from days and weeks The express train arrives in Linfen to Xi'an (home of the clay warriors found of talk and gathering oral history from from Beijing in the early morning, around in the tomb of the Emperor Ching Shi students, colleagues and friends. -

Tumbaga-Metal Figures from Panama: a Conservation Initiative to Save a Fragile Coll

SPRING 2006 IssuE A PUBLICATION OF THE PEABODY MUSEUM AND THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY • 11 DIVINITY AVENUE CAMBRIDGE, MA 02138 DIGGING HARVARD YARD No smoking, drinking, glass-break the course, which was ing-what? Far from being a puritani taught by William Fash, cal haven, early Harvard College was a Howells director of the colorful and lively place. The first Peabody Museum, and Harvard students did more than wor Patricia Capone and Diana ship and study: they smoked, drank, Loren, Peabody Museum and broke a lot of windows. None of associate curators. They which was allowed, except on rare were assisted by Molly occasion. In the early days, Native Fierer-Donaldson, graduate American and English youth also stud student in Archaeology, ied, side by side. Archaeological and and Christina Hodge, historical records of early Harvard Peabody Museum senior Students excavating outside Matthews Hall. Photo by Patricia bring to life the experiences of our curatorial assistant and Capor1e. predecessors, teaching us that not only graduate student in is there an untold story to be Archaeology at Boston unearthed, but also, that we may learn University. ALEXANDER MARSHACK new perspectives by reflecting on our Archaeological data recovered from ARCHIVE DONATED TO THE shared history: a history that reaches Harvard Yard enriches our view of the PEABODY MUSEUM beyond the university walls to local seventeenth- through nineteenth-cen Native American communities. tury lives of students and faculty Jiving The Peabody Museum has received the The Fall 2005 course Anthropology in Harvard Yard. In the seventeenth generous donation of the photographs 1130: The Archaeology of Harvard Yard century, Harvard Yard included among and papers of Alexander Marshack brought today's Harvard students liter its four buildings the Old College, the from his widow, Elaine. -

Adaptation and Invention During the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China

Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation D'Alpoim Guedes, Jade. 2013. Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11002762 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China A dissertation presented by Jade D’Alpoim Guedes to The Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Anthropology Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2013 © 2013 – Jade D‘Alpoim Guedes All rights reserved Professor Rowan Flad (Advisor) Jade D’Alpoim Guedes Adaptation and Invention during the Spread of Agriculture to Southwest China Abstract The spread of an agricultural lifestyle played a crucial role in the development of social complexity and in defining trajectories of human history. This dissertation presents the results of research into how agricultural strategies were modified during the spread of agriculture into Southwest China. By incorporating advances from the fields of plant biology and ecological niche modeling into archaeological research, this dissertation addresses how humans adapted their agricultural strategies or invented appropriate technologies to deal with the challenges presented by the myriad of ecological niches in southwest China. -

漢基控股有限公司* (Incorporated in Bermuda with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 412) R13.51A (Warrant Code: 1248)

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt about any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should R14.63(2b) consult your licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities, bank manager, solicitor, certified public accountant or other professional advisers. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Heritage International Holdings Limited (“Company”), you should at once hand this circular together with the enclosed form of proxy to the purchaser or transferee or to licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no R14.58(1) responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. HERITAGE INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED App1B 1 漢基控股有限公司* (Incorporated in Bermuda with limited liability) (Stock Code: 412) R13.51A (Warrant Code: 1248) MAJOR TRANSACTION IN RELATION TO ACQUISITION OF THE ENTIRE ISSUED SHARE CAPITAL OF GLOBAL CASTLE INVESTMENTS LIMITED AND NOTICE OF SPECIAL GENERAL MEETING A notice convening the SGM to be held at 30/F., China United Centre, 28 Marble Road, North Point, Hong Kong on Thursday, 28 March 2013 at 9:00 a.m. is set out on pages SGM-1 to SGM-2 of this circular. -

Climatic Disasters and Defense Countermeasures of the Oasis City

Climatic Disasters and Defense Countermeasures of the Oasis City on Tropic of Cancer Duan Peng LingZhao JiaFengWeng (Zhaoqing Meteorological Observatory, Guangdong, China 526060) Abstract:This paper analyzes the climatic characteristics and climatic disasters of the oasis city of zhaoqing on the tropic of Cancer .The result indicates that the frequent meteorological droughts, and the frequent Geological disasters caused by heavy rain,and the high temperature,which cause energy consumption and electricity consumption, and the smog, the severe thunderstorms and short-term strong winds which effect on urban transport. And the impact of dominant winds on industrial layout, and some defense countermeasures have been put forward:Ecological city planning should consider meteorological risk areas according to meteorological conditions; Climate demonstration must be conducted for major urban projects;Strengthen the relevant research of meteorological planning for eco-city construction and other countermeasures. These efforts will provide scientific data for the government departments to plan for the sustainable development of ecological cities. Key words: Oasis City; Climate characteristics; Climate disasters;Countermeasure 1.Introduction Zhaoqing City, Guangdong Province is located in the central and western part of Guangdong Province. It is located in the south of Nanling, with high mountains in the Northwest and low in the Southeast. The mountains, hilly basins, river valleys, and plains criss-cross each other. The topography is complex and diverse. The entire territory of Zhaoqing is between 22 ° 47 ′ and 24 ° 24 ′ north latitude, and the Tropic of Cancer runs through it. Due to the subtropical monsoon and monsoon humid climate and the high and low terrain in the Northwest and Southeast, the climate is hot and rainy.