Extended Interview with Demis Volpi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VALIA SEISKAYA Seiskaya Students Have Compiled an Outstanding Record of Achievement

VALIA SEISKAYA Seiskaya students have compiled an outstanding record of achievement. Through the years, full scholarships have been awarded by every major institution for which they Russian-born Valia Seiskaya took her first ballet have auditioned, including schools affiliated with American Ballet Theatre (ABT), lessons in Greece at the age of six. Her teacher was New York City Ballet, and the San Francisco, Houston, Joffrey, Pacific Northwest, Adam Morianoff, also a Russian émigré. (Valia Pittsburgh, Eliot Feld, and Boston Ballets. Some of the many dance companies was experiencing difficulty learning Greek; thus, Seiskaya students have joined: ABT (5), Atlanta Ballet (2), Boston (2), Ballet West, it was natural for her mother to seek out a fellow Fort Worth, Hartford, Pacific Northwest, Pittsburgh, Royal Swedish, State Ballet of countryman.) At nine she became a scholarship Missouri, Ballet Arizona, Tennessee, Milwaukee (3), New Jersey, Alabama, Washington, student, showing prodigious technique—for ex- Louisville, Austin, Tulsa Ballets and Momix. ample, entrechat huit, eight beats, in centre—by age ten. Pointe work also started at ten, character In 1994 Seiskaya student Michael Cusumano captured a bronze medal and Special ballet at twelve. Thereafter, Mme. Seiskaya rapidly Commendation at the International Ballet Competition (IBC) in Varna, Bulgaria and a coveted Jury Award (a gold medal-level award) at the Prix de Danse, Paris, France. developed the combination of strong technique and Valia Seiskaya was nominated that year as the Best Teacher and Coach at Varna, one high elevation which would become her hallmark of the few Americans ever to be so honored. as a professional. -

Bruhn, Erik (1928-1986) Erik Bruhn (Second from Left) Visiting Backstage at by John Mcfarland the New York City Ballet

Bruhn, Erik (1928-1986) Erik Bruhn (second from left) visiting backstage at by John McFarland the New York City Ballet. The group included (left Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. to right) Diana Adams, Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Bruhn, Violette Verdy, Sonia Arova, and Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Rudolph Nureyev. Erik Bruhn was the premier male dancer of the 1950s and epitomized the ethereally handsome prince and cavalier on the international ballet stage of the decade. Combining flawless technique with an understanding of modern conflicted psychology, he set the standard by which the next generation of dancers, including Rudolf Nureyev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Peter Schaufuss, and Peter Martins, measured their success. Born on October 3, 1928 in Copenhagen, Bruhn was the fourth child of Ellen Evers Bruhn, the owner of a successful hair salon. After the departure of his father when Erik was five years old, he was the sole male in a household with six women, five of them his seniors. An introspective child who was his mother's favorite, Erik was enrolled in dance classes at the age of six in part to counter signs of social withdrawal. He took to dance like a duck to water; three years later he auditioned for the Royal Danish Ballet School where he studied from 1937 to 1947. With his classic Nordic good looks, agility, and musicality, Bruhn seemed made for the August Bournonville technique taught at the school. He worked obsessively to master the technique's purity of line, lightness of jump, and clean footwork. Although Bruhn performed the works of the Royal Danish Ballet to perfection without any apparent effort, he yearned to reach beyond mere technique. -

Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York –

Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York - Tous droits réservés - # Symbol denotes creation of role Commencing with the year 1963, only the first performance of each new work to his repertoire is listed. London March 2,1970 THE ROPES OF TIME # The Traveler The Royal Ballet; Royal Opera House With: Monica Mason, Diana Vere C: van Dantzig M: Boerman London July 24,1970 'Tribute to Sir Frederick Ashton' Farewell Gala. The Royal LES RENDEZ-VOUS Ballet,- Royal Opera House Variation and Adagio of Lovers With: Merle Park Double debut evening. C: Ashton M: Auber London July 24,1970 APPARITIONS Ballroom Scene The Royal Ballet; Royal Opera House The Poet Danced at this Ashton Farewell Gala only. With: Margot Fonteyn C: Ashton M: Liszt London October 19, 1970 DANCES AT A GATHERING Lead Man in Brown The Royal Ballet; Royal Opera House With: Anthony Dowell, Antoinette Sibley C: Robbins M: Chopin Marseille October 30, 1970 SLEEPING BEAUTY Prince Desire Ballet de L'Opera de Morseille; Opera Municipal de Marseille With: Margot Fonteyn C: Hightower after Petipa M: Tchaikovsky Berlin Berlin Ballet of the Germon Opera; Deutsche Opera House November 21, 1970 Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York – www.nureyev.org Copyright Marilyn J. La Vine © 2007 New York - Tous droits réservés - # Symbol denotes creation of role SWAN LAKE Prince Siegfried With: Marcia Haydee C: MacMillan M: Tchaikovsky Brussels March 11, 1971 SONGS OF A WAYFARER (Leider Eines Fahrenden Gesellen) # Ballet of the 20#, Century; Forest National Arena The Wanderer With: Paolo Bortoluzzi C: Bejart M: Mahler Double debut evening. -

Prima Ballerina Bio & Resume

Veronica Tennant, C.C. Prima Ballerina Bio & Resume Veronica Tennant, during her illustrious 25-year career as Prima Ballerina with The National Ballet of Canada - won a devoted following on the international stage as a dancer of extraordinary versatility and dramatic power. Born in London England, Veronica Tennant started ballet lessons at four at the Arts Educational School, and with her move to Canada at the age of nine, started training with Betty Oliphant and then the National Ballet School. While she missed a year on graduation due to her first back injury, she entered the company in 1964 as its youngest principal dancer. Tennant was chosen by Celia Franca and John Cranko for her debut as Juliet. She went on to earn accolades in every major classical role and extensive neo-classical repertoire as well as having several contemporary ballets choreographed for her. She worked with the legendary choreographers; Sir Frederick Ashton, Roland Petit, Jiri Kylian, John Neumeier, and championed Canadian choreographers such as James Kudelka, Ann Ditchburn, Constantin Patsalas and David Allan. She danced across North and South America, Europe and Japan, with the greatest male dancers of our time, including Erik Bruhn (her mentor), and Rudolf Nureyev, Anthony Dowell, Peter Schaufuss, Fernando Bujones and Mikhail Baryshnikov (immediately after he defected in Toronto, 1974). She was cast by Erik Bruhn to dance his La Sylphide with Niels Kehlet when Celia Franca brought The National Ballet of Canada to London England for the first time in 1972; and was Canada’s 'first Aurora' dancing in the premiere of Rudolf Nureyev's Sleeping Beauty September 1, 1972 and at the company's debut at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, 1973. -

Swan Lake – Student Viewing Guide: Grade 10-12

Swan Lake – Student Viewing Guide: Grade 10-12 Guidelines for Teachers Curriculum Connections: • Dance • Writing • Media Literacy Learning Goals: • Experiencing, responding to and analyzing classical ballet through reflective and critical writing • Recognizing different characteristics of classical ballet movement and choreography in Act I Scene II of Erik Bruhn’s Swan Lake • Understanding how dancers tell stories in classical ballet Big Ideas: • Swan Lake is an example of ballet from the classical period • Classical ballet choreography achieves a satisfying visual effect through balance, structure and harmony • Classical ballet choreography often showcases virtuosic technique separately from storytelling Big Questions: • What kind of visual effect does the choreographer achieve through geometric formations? • How do classical ballet choreographers tell stories? • How are classical ballets collaborative productions? • How does choreography evolve over time? • Why do ballet companies still perform Swan Lake? Getting Started: • Assign the whole guide to your students as an extended project or pick and choose sections to assign at different times Watch Swan Lake, Act 1 Scene II: www.nbs-enb.ca/loveballet PAGE 1 Fall in Love with Ballet | Swan Lake – Student Viewing Guide: Grade 10-12 Swan Lake – Student Viewing Guide: Grade 10-12 Student Viewing Guide Swan Lake, Act 1 Scene II Choreography: Erik Bruhn Music: Pyotr Tchaikovsky Pianist: Marina Surgan NBS Principals Staged and Rehearsed by: Sergiu Stefanschi, Vera Timashova Soloists and Corps de Ballet Staged and Rehearsed by: Martine Lamy Soloists and Corps de Ballet Assisted by: Ilze Titova Synopsis: Erik Bruhn’s Swan Lake is one of the most beloved versions of this magical classical ballet, and demands both technical skill and artistry of all its dancers. -

THE NUTCRACKER’ December 5 at GSU’S Center for Performing Arts

Contact: Sharon Banaszak Governors State University Phone: (708) 235.2812 Email: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Continue Your Holiday Tradition with SALT CREEK BALLET’s ‘THE NUTCRACKER’ December 5 at GSU’s Center for Performing Arts November 16, 2015 (University Park, IL) – The highly acclaimed Salt Creek Ballet returns with the lovable holiday classic The Nutcracker. The production was recently revamped with all new sets and costumes, and features internationally recognized guest dancer, Yury Yanowsky, partnering Salt Creek Ballet dancer, Stefanee Montesantos. Bring the whole family to the Center for Performing Arts at Governors State University on Saturday, December 5th at 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. for the perfect start to the holiday season. Families will enjoy a ‘Sugar Plum Party’ between the performances at 3 p.m. where they can take pictures with Santa, enjoy hot chocolate and cookies and enter to win prizes. The Chicago Sun-Times calls the production “…a solid, professional ‘Nutcracker’,” and The Chicago Tribune calls it “a plum performance.” An enchanting holiday tradition, this year’s production of The Nutcracker features a cast of 100 dancers, including local children and young adults ages 8-17 from the school of the Salt Creek Ballet. This year, internationally recognized Yury Yanowsky will take to the stage with SCB’s Stefanee Montesantos as Cavalier and Sugar Plum Fairy. Mr. Yanowsky spent the last fifteen years as a Principal Dancer with Boston Ballet. He is a first prize winner of the Prix de Laussane and a Silver Medalist at the International Ballet Competition Varna in Bulgaria, in addition to being a Senior Division Silver Medalist at the 1994 USA International Ballet Competition. -

Ballet Styles

STYLES OF BALLET This document serves to help dance instructors and students differentiate the various styles of ballet. Each major style is described with a combination of helpful text, images and video links. Table of Contents STYLES OF DANCE: American / Balanchine Ballet…………………………...….. Page 3 Classical / Romantic Ballet ………………………..……..... Page 4 Contemporary Ballet………………………….……….……. Page 5 English / Royal Academy of Dance ……..….………….…. Page 6 Danish / Bournonville Ballet…………………………….….. Page 7 French Ballet / Paris Opera Ballet School …..……….…... Page 8 Italian / Cecchetti Ballet……………………………..……... Page 9 Russian / Vaganova Ballet……………………………….….. Page 10 Copyright © 2020 Ballet Together - All Rights Reserved. Page 2 AMERICAN / BALANCHINE STYLE OF BALLET Photo on left: George Balanchine and Arthur Mitchell | Source Photo on right: Serenade | Ashley Bouder and New York City Ballet dancers | Source FOUNDED: By George Balanchine in 1934 in New York City, NY, U.S.A.. DESCRIPTION: This style was developed by choreographer George Balanchine, a graduate of Vaganova Ballet Academy. After immigrating from Russia to New York City, Balanchine founded The School of American Ballet, where he developed his specific style of ballet and later began the professional company, The New York City Ballet. Also considered neoclassical ballet, this style is thought to mirror the vibrant and sporty American style in contrast to the more noble and tranquil Russian and European ballet style counterparts. Balanchine is celebrated worldwide as the “father of American ballet”and choreographed 465 ballets in his lifetime. DISTINCT STYLE FEATURES: - While Balanchine’s style took initial inspiration from the traditional Russian method, he rejected classical stiffness for jazzy, athletic movements. - The characteristics of this style include: extreme speed, an athletic quality, a deep plié, an emphasis on line, en dehors pirouettes taken from a lunge in fourth position with a straight back left. -

Giselle – the Vancouver

TAIWAN MEETS VIETNAM Festival reveals cultural links B3 RAMEN IN NORTH VAN Sibling duo SCENE opens shop B4 VANCOUVER SUN THURSDAY, AUGUST 29, 2019 SECTION B Social media IN MOTION Choreographer gives classic ballet modern overhaul STUART DERDEYN old prodigy. She first encountered the project with Beamish in 2016. Giselle is a masterwork of the clas- “Joshua was just starting the sical ballet. Probably every compa- very first ideas of @giselle and I ny in the world has presented the was involved in the workshop pro- tragedy of an innocent, beautiful cess of making the Willis dance in young peasant girl named Giselle Act 2, which is core to the ballet,” who falls hard for the calculated Hurlin says. flirtations of a sleazy rich noble- “I think the way that he is incor- man named Albrecht. After she porating realistic storytelling into dies of heartbreak, he must con- the work is really interesting for tend with supernatural conse- Josh Beamish 2019 and the technology is very quences for his cruel actions. much a part of modern daily life. As Giselle was first played in Paris @GISELLE a classical dancer, this is more con- in 1841, going on to become one When: Sept. 5-7, 7:30 p.m. temporary to me, but those lines of the most performed ballets in Where: Vancouver Playhouse, are becoming increasingly blurred history. It’s also one of the hard- 600 Hamilton St. and I’m still in pointe shoes.” est roles to dance. Any updating Tickets and info: From $35 Right after @giselle, Hurlin re- of the production goes up against at eventbrite.com turns to New York to launch the 178 years of proven, crowd-pleas- fall season at the American Bal- ing performances provided by edy, she returns to take on her let Theatre and prepare for that high-flyingballerinas . -

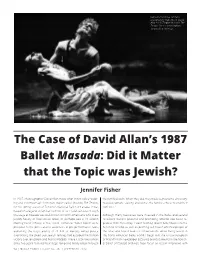

The Case of David Allan's 1987 Ballet Masada: Did It Matter That the Topic

Dancers Veronica Tennant and Gregory Osborne in David Allan's 1987 ballet Masada: The Zealots. Photo: John Mahler/ Toronto Star Archives The Case of David Allan’s 1987 Ballet Masada: Did it Matter that the Topic was Jewish? Jennifer Fisher In 1987, choreographer David Allan made what critics called “a dar- the fortified walls. When they did, they made a gruesome discovery: ing and controversial” 40-minute ballet called Masada, The Zealots, to avoid capture, slavery, and worse, the families chose to end their for the spring season of Toronto’s National Ballet of Canada. It was own lives.1 based on a legend unfamiliar to most of its 27-dancer-cast, though the siege at Masada was well-known to North Americans who knew Although many resources were invested in the ballet and several Jewish history or had visited Israel, or perhaps saw a TV version reviewers found it powerful and promising, Masada was never re- starring Peter O’Toole in the 1980s. Historical “Ballet Notes” were peated. With this essay, I want to bring Allan’s ballet back into the provided to the press and to audiences in pre-performance talks, historical record, as well as pointing out how it affected people at explaining the tragic events of 74 A.D. at Herod’s winter palace the time, and how it leads to conversations about being Jewish in overlooking the Dead Sea. Jewish families had escaped the Roman the North American ballet world. I begin with the critical reception victory over Jerusalem and fled to Masada. There it took the Roman of Masada from newspaper accounts and documents in the Nation- army two years to build their siege ramp and finally break through al Ballet of Canada archives, then focus on recent interviews with 54 | DANCE TODAY | ISSUE No. -

Page 1 Outstanding Events of the Final Weeks of AMERICAN

Outstanding Events of the Final Weeks of AMERICAN BALLET THEATRE'S Gala Christmas Season at the Academy ************************************ Three of the world's most popular ballets, SWAN LAKE, GISELLE and COPPELIA, are prominent in the current repertory. GISELLE, acclain~d at the World Premiere of this new production last July at the Metro politan Opera House, is the greatest of the romantic ballets and will have its first performance this season Tuesday evening, December 17th. The Brooklyn Academy will present the World Premiere of COPPELIA, the enchanting children's comedy ballet, for eight perfonmances dur ing Christmas week, the first on Tuesday afternoon, December 24th, at 2 :00 p.m. These magnificent full-length productions will feature four of the world's greatest dancers. CARLA FRACCI Prima ballerina of La Scala in Milan, Miss Fracci has been hailed by the critic of DANCE NEWS as "the greatest GISELLE of her generation, following in the footsteps of Markova, Ulanova and Alonso. She is the perfection of the romantic ballerina." Clive Barnes in the N.Y. TIMES rhapsodized, 11a dream of a dancer." ERIK BRUHN The incredible Danish star is unique among the dancers of today. "The peerless male dancer of our time," wrote Clive Barnes in the N.Y. TIMES. ''The greatest male dancer in the world today," said Rudolph Nureyev in an interview in TIME MAGAZINE. ELEANOR D1 ANTUONO "Miss D1 Antuono could probably complete her dazzling fouettes on the back of a galloping horse," said John MarHn, dean of America's dance critics. GISELLE and COPPELIA display Miss D'Antuono's virtu osity and her breathtaking technique in perfect contrast. -

Prince of Denmark 99

Daily Telegraph Dec 28 1999 Prince of Denmark Danish star Johan Kobborg is one of the Royal Ballet’s brightest new hopes, says Ismene Brown IT was 8.30am and Heathrow’s Terminal 1 was filling up with passengers. I studied their feet. It was my best chance of recognising Johan Kobborg off-duty. “I’ll turn out,” he’d promised on the phone - meaning his legs. And sure enough, into my view hove a pair of duck- like, waddling feet. The brilliant new male dancer at the Royal Ballet has spotted me foot-watching, and was playing his part. There is nothing very odd about meeting Kobborg at an airport for an interview. For such a star aeroplanes are the equivalent of trains for the rest of us. Only four days before Christmas, he was off to Bilbao in Spain for two gala performances; he would whizz back home to Copenhagen for Christmas with his family, before returning to London yesterday ready for his debut in the Royal Ballet’s Nutcracker this afternoon. Kobborg’s appearance as a Prince is symbolic. A year ago six Royal Ballet men quit to dance in Japan. Foreign leading men were hurriedly drafted in. First it was the pantherine Cuban Carlos Acosta who joined, replacing Tetsuya Kumakawa, but the new Prince on the block whose name caused a frisson of delight among cognoscenti was this young Dane, as blond and mischievous as Acosta is dark and brooding. Denmark, a nation of only five million people, with a ballet tradition reaching back before 1600, produces a startling, disproportionate number of the top male dancers more consistently even than the vast ballet nationsl Russia and America. -

This Program Is Partially Supported by a Grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency. Welcome Back to Your Holiday Tradition! SALT CREEK BALLET’s ‘THE NUTCRACKER’ at Governors State University Center for Performing Arts The highly acclaimed Salt Creek Ballet returns to GSU Center with the lovable holiday classic The Nutcracker. The production was recently revamped with all new sets and costumes, and features internationally recognized guest dancer, Yury Yanowsky, partnering with Salt Creek Ballet dancer, Stefanee Montesantos. We are glad to welcome your whole family to the Center for Performing Arts at Governors State University on Saturday, December 5th at 1 p.m. and 5 p.m. for the perfect start to your holiday season! Families, please enjoy our ‘Sugar Plum Party’ between the performances at 3 p.m. where you can take pictures with Santa, enjoy hot chocolate and cookies, and enter to win fun prizes. The Chicago Sun-Times calls the production “…a solid, professional ‘Nutcracker’,” and The Chicago Tribune calls it “a plum performance.” An enchanting holiday tradition, this year’s production of The Nutcracker features a cast of 100 dancers, including local children and young adults ages 8-17 from the school of the Salt Creek Ballet. This year, internationally recognized Yury Yanowsky will take to the stage with SCB’s Stefanee Montesantos as Cavalier and Sugar Plum Fairy. Mr. Yanowsky spent the last fifteen years as a Principal Dancer with Boston Ballet. He is a first prize winner of the Prix de Laussane and a Silver Medalist at the International Ballet Competition Varna in Bulgaria, in addition to being a Senior Division Silver Medalist at the 1994 USA International Ballet Competition.