Developing a Soil Health Testing Protocol for Arable Cropping Systems in Saskatchewan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soil Quality Characteristics As Affected by Continuous Rice Cultivation

agriculture Article Soil Quality Characteristics as Affected by Continuous Rice Cultivation and Changes in Cropping Systems in South China Xiangning Ren 1,2,3, Feixiang Chen 1,2,3, Tao Ma 1,2 and Yueming Hu 1,2,3,4,* 1 College of Natural Resources and Environment, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China; [email protected] (X.R.); [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (T.M.) 2 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Land Use and Consolidation, Guangzhou 510642, China 3 South China Academy of Natural Resources Science and Technology, Guangzhou 510610, China 4 State Key Laboratory of Plateau Ecology and Agriculture, Qinghai University, Xining 810016, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-186-8888-2020; Fax: +86-20-8528-3140 Received: 12 August 2020; Accepted: 23 September 2020; Published: 30 September 2020 Abstract: This study was conducted to elucidate how changes in critical soil quality characteristics relate to continuous rice cultivation and changes in cropping systems and fertilization in South China over the time span 1980 to 2017. Soil pH, soil organic matter (SOM), total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (AP) and potassium (AK) were determined for the samples taken in 2017 and compared to results from the paired samples collected in 1980 by grouping all samples into four cropping systems: continuous paddy fields, new paddy fields developed from uplands, continuous uplands, and new uplands developed from paddy soils. The results show a significant increase in soil pH, AP and AK in all cropping systems, which was, however, coupled with low fertilizer use efficiency. -

Soils – Fundamental Concepts

NRCS Soil: Fundamental Concepts Scoop on Soil Educational CD May 2006 Soils – Fundamental Concepts The Soil In Perspective: A fundamental knowledge of soil science is a prerequisite to meeting the many natural resource challenges that will face humanity in the 21st Century. It is also true that the study of soils can be both fascinating and intellectually satisfying. It is in the soils that we are able to observe all of the principles of biology, chemistry, and physics at work. It is the understanding of these principles which enables us to minimize the degradation and destruction of one of our most important natural resources. Much of our life’s activities and pursuits are related to and influenced by the behavior of the soil around our houses, roads, septic and sewage disposal systems, airports, parks, farms, forests, schools, and shopping centers. It is essential that conservation professionals understand the soils on which we build and design and work. In any field of natural resources, it is important to understand the soil properties which impact the application of technology as we use it to preserve and protect our most basic natural resource, our soils. Soil Defined: We have several definitions of soil depending on the discipline providing the definition: Geologic definition – loose surface of the earth as distinguished from solid bedrock. (Support of plant life not required) Traditional definition – material which nourishes and supports growing plants. (Includes rocks, water, snow, and even air – all of which are capable of supporting plant life) Component definition – mixture of mineral matter, organic matter, water and air. -

Soil Science 1

Soil Science 1 Soil Chemistry and Plant Nutrition: Nutrient cycling; nutrient recovery from wastewater; molecular visualization of soil minerals SOIL SCIENCE and molecules; soil acidification. The Department of Soil Science provides undergraduate and graduate Professor William Bleam education in the environmental, agricultural, and natural resource Surface and Colloid Chemistry: Physical chemistry of soil aspects of soils. Areas of emphasis include soil ecology; soil erosion colloids and sorption processes, chemistry of humic substances, management; soil fertility and plant nutrition; soil physical and chemical factors controlling biological availability of contaminants to characterization; biogeochemistry; urban soils; soil carbon; soil health; microorganisms, magnetic resonance and synchrotron studies of soil contaminants; waste management; pedology; and land-use analysis. adsorption and precipitation. Soils are a critical natural resource in environmental protection, food Assistant Professor Zachary Freedman and fiber production, turf and grounds management, rural and urban planning, and waste disposal. All of these facets are integrated into the Soil microbiology, ecology and sustainability: Effects of environmental department's course offerings and research programs. Soil Science change on biogeochemical cycles; community ecology and trophic majors prepare for professional, technical, consulting, and project dynamics; forest soil ecology; soil organic matter dynamics; sustainable positions in environmental sciences, ecology and restoration, crop and agroecosystems; bio-based product crop production on marginal lands. timber production, soil informatics, soil conservation, environmental pollution control, turf and grounds management, and land-use planning. Professor Alfred Hartemink Please contact the department for further information on career Pedology and Digital Soil Mapping: Pedology, soil carbon; digital soil opportunities. mapping; tropical soils; history and philosophy of soil science. -

The Soil Story Curricular Guide

THE SOIL STORY CURRICULUM Rebuilding Healthy Soil for Carbon Cycle Balance Earth’s Systems Photosynthesis Healthy Soil Lead Authors: Whitney Cohen | Education Director, Life Lab Food & Farming Carrie Strohl, PhD | Educational Consultant Taking Action Contributors: Annie Martin | Business Program, Kiss the Ground Arlae Castellanos | Sustainability Tracking Program Manager, Green Schools Alliance Craig Macmillan, PhD | Technical Program Manager, Vinyard Team Didi Pershouse | Director, Learning Resources Don Smith | Storytelling Team, Kiss the Ground Emily Harris, PhD | Research Scientist, BSCS Science Learning Finian Makepeace | Co-Founder, Kiss the Ground Ilana Lowe | 5th Grade Lead Science Teacher, Main Street Elementary Jessica Handy, RDN | Education Program, Kiss the Ground Karen Rodriguez | Former Operations Manager, Kiss the Ground A Middle School Lauren Tucker | Executive Director, Kiss the Ground Curriculum by Leslie Rogers | Director of Education, Atlas Organics Liz Henry | Senior Consultant, Crecer Strategies Markos Major | Director, Climate Action Now Paul Hawken | Author and Environmentalist Designer: Michelle Uyeda | Graphic Designer, Kiss the Ground + Thank you to our sponsors: About 1 THE SOIL STORY CURRICULAR GUIDE The Soil Story Curricular Guide was created through a collaborative partnership between Kiss the Ground and Life Lab. It serves as a supplemental material for teaching middle schoolers Next Generation Science Standards. Kiss the Ground (KTG) is a nonprofit with a mission to inspire participation in the regeneration of the planet, beginning with soil. The organization creates educational curriculum, campaigns, and media to raise awareness and empower individuals to purchase food that supports health soils and a balanced climate. KTG also works with farmers, educators, non government organizations, scientists, students, and policymakers to advocate for regenerative agriculture, raise funds to train farmers, and help brands and businesses to invest in healthy soils. -

Soil Food Web: Implications to Soil Health

Soil Food Web: Implications to Soil Health Dr. Sajeemas “Mint” Pasakdee, Soil Scientist/Agronomist Advisor, Student Operated Organic Farm CIT-Jordan College of Agri. Sci. & Tech., Fresno State 1 Outline • Soil organisms and their interactions • What do soil organisms do? • Where do soil organisms live? • Food web structure • When are soil organisms active? • How is the food web measured? • Living soils—Bacteria; Fungi; Earthworms • Soil Environment 2 Organisms & Their Interaction 3 4 What do soil organisms do? Soil organisms support plant health as • decompose organic matter, • cycle nutrients, • enhance soil structure, • control the populations of soil organisms including crop pests. 5 Organic Matter • Food sources for soil organisms • Agricultural top soil ~1-6% (In CA, ~1-3% SOM) 6 Where do soil organisms live? • Around roots(rhizosphere) • Plant litter (C sources) • Humus (stabilized organic matter) • Surface of soil aggregates 7 Typical Food Web Structure • bacterial-dominated food webs o Grassland & Agri Soils o Ratio of fungi to bacteria, ~1:1 for productive agri. soils • fungal-dominated food webs o Ratio of fungal to bacterial, ~5:1 to 10:1 in a deciduous forest and 100:1 to 1000:1 in a coniferous forest 8 9 When are soil organisms active? 10 How is the food web measured? • Counting. Organism groups (bacteria, protozoa, arthropods, etc.); or subgroups (bacterial-feeding, fungal-feeding, and predatory nematodes), are counted and through calculations, can be converted to biomass. • Measuring activity levels. The amount of by-products, i.e., respiration (CO2); nitrification and decomposition rates • Measuring cellular constituents. Biomass carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorus; Enzymes; Phospholipids and other lipids; DNA and RNA 11 12 Soil Bacteria • One-celled organisms – generally 4/100,000 of an inch wide (1 µm) • A teaspoon of productive soil generally contains between 100 million and 1 billion bacteria (~two cows per acre). -

Soil Health and Global Sustainability: Translating Science Into Practice

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska January 2002 Soil health and global sustainability: translating science into practice John W. Doran University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub Part of the Agricultural Science Commons Doran, John W., "Soil health and global sustainability: translating science into practice" (2002). Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty. 181. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdaarsfacpub/181 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: Agricultural Research Service, Lincoln, Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications from USDA-ARS / UNL Faculty by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 88 (2002) 119–127 Soil health and global sustainability: translating science into practiceଝ John W. Doran∗ USDA-ARS, 116 Keim Hall, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68583-0934, USA Abstract Interest in the quality and health of soil has been stimulated by recent awareness that soil is vital to both production of food and fiber and global ecosystems function. Soil health, or quality, can be broadly defined as the capacity of a living soil to func- tion, within natural or managed ecosystem boundaries, to sustain plant and animal productivity, maintain or enhance water and air quality, and promote plant and animal health. Soil quality and health change over time due to natural events or human im- pacts. -

Soil Health Scavenger Hunt

K-12 IYS Activity Soil Health Scavenger Hunt Summary • Supported by other organizations For centuries, humans have used Materials (per student, group etc.) (look for logos or links to other groups plants, soils, and minerals to improve — Whiteboard or flipchart and related to soils and health) health. Most medicines today are de- markers • Lists the author(s) of the information rived from a plant or mineral. For a list — Soil and Health Scavenger Hunt of examples, visit http://publications. Worksheet • Appealing design and is easy to read nigms.nih.gov/medbydesign/chapter3. — Option 1—Internet access and • Has been updated recently (within html#c1; ability to project websites the past 6-9 months) Even today, scientists are still • URLs that end in .gov or .edu studying the soil to hunt for microbes — Option 2—Printouts of websites that can improve human health and The language or wording of the site can fight chronic disease. This activity is Ages of Audience help you determine whether the website is about pedology or the study of soil. 4th–6th grades promoting facts or opinions. Here are some There are many websites associated words that signal the reader to be cautious with the field of pedology. Some of Time Needed because they are often used when sharing them are accurate, and others are not. opinions: This activity investigates how to evalu- 45-60 minutes, depending on the number ate sources of information for credibil- of participants Must be proven ity and usefulness. (reference a source when making a Generalizations Judgments statement) Methods/Procedures Learning Objectives/ All Bad Is caused by 1. -

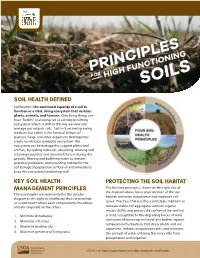

Principles for High Functioning Soils 2

PRINCIPLES FOR HIGH FUNCTIONINGSOILS SOIL HEALTH DEFINED Soil health is the continued capacity of a soil to function as a vital, living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans. Only living things can have “health,” so viewing soil as a living, breathing ecosystem reflects a shift in the way we view and manage our nation’s soils. Soil isn’t an inert growing medium, but rather is the home of billions of bacteria, fungi, and other organisms that together create an intricate symbiotic ecosystem. This ecosystem can be managed to support plants and animals, by cycling nutrients, absorbing, draining and retaining rainwater and snowmelt for use during dry periods, filtering and buffering water to remove potential pollutants, and providing habitat for the soil biological population to flourish and diversify to keep the ecosystem functioning well. KEY SOIL HEALTH PROTECTING THE SOIL HABITAT MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES The first two principles, shown on the right side of the diagram above focus on protection of the soil These principles are represented in the circular habitat: minimize disturbance and maximize soil diagram to the right to emphasize their relationship as a continuum where each complements the others cover. Practices that use these principles maintain or and also depends on the others. increase stable soil aggregates and soil organic matter (SOM), and protect the surface of the soil that 1. Minimize disturbance is most susceptible to the degrading forces of wind 2. Maximize soil cover and water. Maximizing soil cover also buffers against temperature fluctuations that stress plants and soil 3. Maximize biodiversity organisms, reduces evaporation rates, and increases 4. -

Soil Pollution: a Hidden Reality

SOIL POLLUTION: A HIDDEN REALITY THANKS TO THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION SOIL POLLUTION: AHIDDEN ISBN 978-92-5-130505-8 REALITY 9 789251 305058 I9183EN/1/04.18 SOIL POLLUTION AHIDDEN REALITY SOIL POLLUTION AHIDDEN REALITY Authors Natalia Rodríguez Eugenio, FAO Michael McLaughlin, University of Adelaide Daniel Pennock, University of Saskatchewan (ITPS Member) Reviewers Gary M. Pierzynski, Kansas State University (ITPS Member) Luca Montanarella, European Commission (ITPS Member) Juan Comerma Steffensen, Retired (ITPS Member) Zineb Bazza, FAO Ronald Vargas, FAO Contributors Kahraman Ünlü, Middle East Technical University Eva Kohlschmid, FAO Oxana Perminova, FAO Elisabetta Tagliati, FAO Olegario Muñiz Ugarte, Cuban Academy of Sciences Amanullah Khan, University of Agriculture Peshawar (ITPS Member) Edition, Design & Publication Leadell Pennock, University of Saskatchewan Matteo Sala, FAO Isabelle Verbeke, FAO Giulia Stanco, FAO FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2018 DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT Recommended citation Rodríguez-Eugenio, N., McLaughlin, M. and Pennock, D. 2018. Soil Pollution: a hidden reality. Rome, FAO. 142 pp. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

State Soil Health Initiatives: Building Momentum

STATE SOIL HEALTH INITIATIVES: BUILDING MOMENTUM Fishkill Farms, East Fishkill, New York PETER LEHNER ELIZABETH HENDERSON GOALS OF A HEALTHY SOIL LAW • Reduce GHG emissions (CH4, N2O, CO2) • Increase soil carbon • Support key soil health principles (e.g. of NRCS or Rodale Institute): • Maximize soil surface cover • Minimize disturbance of soil • Maximize above- and below-ground diversity • Maintain continuous living roots in soil • Reduce and limit chemical inputs • Incorporate animals on cropland 2 EXISTING STATE HEALTHY SOIL LAWS (1) • California: SB859 and AB1613 (2016) • Creates Healthy Soils Program • Defines healthy soils, coordinate agency efforts, R&D, incentives, education • AB2377 (2018) – 5% of Climate Smart Ag funding for technical assistance (25% of funds for socially- disadvantaged farmers) • $7.5M for program and demonstrations • Hawaii: HB 1578 (2017) • Identifies, measures, encourages soil health practices • Promotes C sequestration, compost, and agroforestry • $25,000 3 EXISTING STATE HEALTHY SOIL LAWS (2) • Maryland: HB 1063 (2017) • Defines and supports healthy soils by directing the Agricultural Department to support practices through incentives, R&D, possible funding • Oklahoma: HB 1192 (2001) • Creates advisory committee to identify and support practices through R&D, education • Funding and opportunities for carbon trading • Utah: HCR 8 (2015) • Calls on all agencies “with authority to manage lands to increase soil carbon sequestration” 4 PROPOSED STATE HEALTHY SOIL LAWS (1) • Washington: SB 5947 and HB 2095 (2019) • Defines carbon farming as activities that “increase the quantity of organic C in topsoil” • Provides grant funding for on-farm efficiency, regenerative ag practices that enhance soil health, agroforestry • Illinois: SB 1980/HB 2737 and HB 2819 (2019) • Defines soil health, and includes “conservation of soil health” to Soil and Water Conservation Districts Act • Requires soil health practices on land leased for agricultural purposes (Dept. -

Anthropogenic and Inherent Effects on Soil Organic Carbon Across The

sustainability Article Anthropogenic and Inherent Effects on Soil Organic Carbon across the U.S Márcio R. Nunes 1,*, Harold M. van Es 2, Kristen S. Veum 3 , Joseph P. Amsili 2 and Douglas L. Karlen 4 1 USDA-Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment, University Boulevard, Ames, IA 50011–3611, USA 2 Section of Soil and Crop Sciences, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA; [email protected] (H.M.v.E.); [email protected] (J.P.A.) 3 USDA-ARS, Cropping Systems and Water Quality Research Unit, 269 Agricultural Engineering Bldg., University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA; [email protected] 4 USDA-ARS, DL Karlen Consulting LLC, 487 Ashland Ave., St. Pual, MN 55102, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 29 May 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 15 July 2020 Abstract: Soil organic carbon (SOC) influences several soil functions, making it one of the most important soil health indicators. Its quantity is determined by anthropogenic and inherent factors that must be understood to improve SOC management and interpretation. Topsoil ( 15 cm) SOC response ≤ to tillage depth and intensity, cover crops, stover removal, manure addition, and various cropping systems was assessed using 7610 observations from eight U.S. regions. Overall, including cover crops, reducing tillage depth and intensity increased SOC. The positive effects of cover crops were more noticeable in South Central, Northwest, and Midwest regions. Removing high rates (>65%) of crop residue decreased SOC in Midwestern and Southeastern soils. -

Soil and Environment

Open Access Journal of Environmental and Soil Sciences DOI: 10.32474/OAJESS.2019.03.000161 ISSN: 2641-6794 Mini Review Soil and Environment Dustin J Welbourne* Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, USA *Corresponding author: Dustin J Welbourne, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, USA Received: July 17, 2019 Published: July 26, 2019 Mini Review previous term explicitly to uprooted soil [15]. life forms that together help life. Earth’s collection of soil, called some logical definitions separate earth from soil by limiting the Soil is a blend of natural issue, minerals, gases, fluids, and plant development; as a method for water stockpiling, supply and an assortment of reasons. Right off the bat, it is utilized to watch The companion survey procedure is significant in science for the pedosphere, has four significant capacities: as a vehicle for that the creator has not appropriated their work. For instance, by beings. These capacities, in their turn, alter the dirt, and you duplicate gluing from Wikipedia, which, I should include, is quite cleaning; as a modifier of Earth’s air; and, as a territory for living would have known this in the event that you read Wikipedia. The great. Actually, I Figure I may complete this article with another pedosphere interfaces with the lithosphere, the hydrosphere, the air, and the biosphere [1]. The term pedolith, utilized regularly to (Figure 1). On a side note, on the off chance that you are perusing duplicate glue from Wikipedia and incorporate a couple of figures allude to the dirt, means ground stone in the sense “key stone”[2].