Michael of Hanslope 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hanslope, Milton Keynes, MK19 7HL Mawley Hanslope Milton Keynes Buckinghamshire MK19 7HL

Hanslope, Milton Keynes, MK19 7HL Mawley Hanslope Milton Keynes Buckinghamshire MK19 7HL £1,250,000 Mawley is an attractive 6 bedroom detached period property sitting in over 3 acres off a public bridleway with an opportunity to further extend into stunning contemporary living accommodation, and conversion of separate barn into annex and stables, subject to pending planning permission. The property is surrounded by countryside & farmland, - ideal for those looking for a manageable equestrian property. The house, formally two properties converted into one large home, has been extensively yet sympathetically modernised in recent times but still offers scope for further improvements to the rear wing and potential for a combination of conversions and extension to both the house and barn - see our later note. Mawley has well presented accommodation, abundant with character features to include fireplaces exposed beams, stone & brickwork and slate floors. It comprises four reception rooms, two kitchens, six bedrooms and three bath/shower rooms. Plans have been drawn to transform the rear wing, converting the attached barn and adding a heavily glazed extension along with conversion of the separate barn in to an annexe. The property occupies a plot of around 3 acres to include paddocks of around 2.5 acres with its rural setting and adjacent network of bridleways, paths and narrow lanes makes for a prefect home for those wishing to keep horses at home. This is a fabulous property in a stunning setting which must be seen to be appreciated. • EQUESTRIAN PROPERTY • RURAL LOCATION • AROUND 3 ARCES • DETACHED FARM HOUSE • ABUNDANT CHARACTER FEATURES • 4 RECEPTION ROOMS • 6 BEDROOMS • 3 BATH/ SHOWER ROOMS • BARN & YARD • SCOPE TO EXTEND & CONVERT Ground Floor established flower and shrub beds and mature trees. -

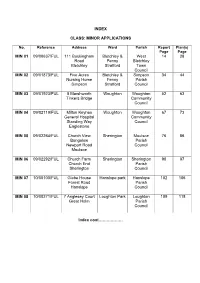

Index Class: Minor Applications Min 01 09/00637

INDEX CLASS: MINOR APPLICATIONS No. Reference Address Ward Parish Report Plan(s) Page Page MIN 01 09/00637/FUL 111 Buckingham Bletchley & West 14 28 Road Fenny Bletchley Bletchley Stratford Town Council MIN 02 09/01873/FUL Five Acres Bletchley & Simpson 34 44 Nursing Home Fenny Parish Simpson Stratford Council MIN 03 09/01923/FUL 8 Marshworth Woughton Woughton 52 63 Tinkers Bridge Community Council MIN 04 09/02119/FUL Milton Keynes Woughton Woughton 67 73 General Hospital Community Standing Way Council Eaglestone MIN 05 09/02264/FUL Church View Sherington Moulsoe 76 86 Bungalow Parish Newport Road Council Moulsoe MIN 06 09/02292/FUL Church Farm Sherington Sherington 90 97 Church End Parish Sherington Council MIN 07 10/00100/FUL Glebe House Hanslope park Hanslope 102 106 Forest Road Parish Hanslope Council MIN 08 10/00271/FUL 7 Anglesey Court Loughton Park Loughton 109 118 Great Holm Parish Council Index cont……………… CLASS: OTHER APPLICATIONS No. Reference Address Ward Parish Report Plan(s) Page Page OTH 01 09/01872/FUL 1 Rose Cottages Wolverton Wolverton & 122 130 Mill End Greenleys Wolverton Mill Town Council OTH 02 09/01907/FUL 6 Twyford Lane Walton park Walton 135 140 Walnut Tree parish Council OTH 03 09/02161/FUL 16 Stanbridge Stony Stony 143 148 Court Stratford Stratford Stony Stratford Town Council OTH 04 09/02217/FUL 220A Wolverton Linford North Great Linford 152 159 Road Parish Blakelands Council OTH 05 10/00117/FUL 98 High Street Olney Olney Town 162 166 Olney Council OTH 06 10/00049/FUL 63 Wolverton Newport Newport 168 174 Road Pagnell North Pagnell Newport Pagnell Town Council OTH 07 10/00056/FUL 24 Sitwell Close Newport Newport 177 182 Newport Pagnell Pagnell North Pagnell Town Council CLASS: OTHER APPLICATIONS – HOUSES IN MULTIPLE OCCUPATION No. -

17/00838/OUT Description Outline Application for the Development Of

ITEM 7(a) Application Number: 17/00838/OUT Description Outline application for the development of 200 dwelling houses, with all matters reserved AT Land to the East of, Eastfield Drive, Hanslope, FOR SiteplanUK LLP Target: 30th June 2018 Extension of Time: No Ward: Newport Pagnell North And Hanslope Parish: Hanslope Parish Council Report Author/Case Officer: Paul Keen Deputy Development Management Manager Contact Details: [email protected], 01908253239 Team Manager: Tracy Darke - 01908 252394, [email protected] 1.0 RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that planning permission is refused for the reasons set out in section 7.0 of this report. 2.0 INTRODUCTION 2.1 The site 2.1.1 The application site is located adjacent to the eastern settlement boundary of Hanslope and 11km from central Milton Keynes. The site itself is generally flat, low- lying, grassland used for pastoral grazing, denoted by well-maintained mature hedgerow, with trees along its southern, western and eastern boundaries. It is currently within agricultural use (Grade 3 classification). 2.1.2 The site lies outside the development boundary of Hanslope and therefore within the open countryside. The site is however immediately adjacent to existing residential properties along Eastfield Drive and Newport Road. 2.1.3 Hanslope is defined as a ‘Selected Village’ within the Milton Keynes Core Strategy 2013. 2.1.4 There are a number of routes within the locality, the main routes being Newport Road adjacent to the south-east and Gold Street/Park Road/Long Street Road to the west at approximately 200 metres. -

Buckingham Share As at 16 July 2021

Deanery Share Statement : 2021 allocation 3AM AMERSHAM 2021 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 16-Jul-21 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4642 AMERSHAM ON THE HILL 75,869 44,973 30,896 59.3 DD S4645 AMERSHAM w COLESHILL 93,366 55,344 38,022 59.3 DD S4735 BEACONSFIELD ST MARY, MICHAEL & THOMAS 244,244 144,755 99,489 59.3 DD S4936 CHALFONT ST GILES 82,674 48,998 33,676 59.3 DD S4939 CHALFONT ST PETER 88,520 52,472 36,048 59.3 DD S4971 CHENIES & LITTLE CHALFONT 73,471 43,544 29,927 59.3 DD S4974 CHESHAM BOIS 87,147 51,654 35,493 59.3 DD S5134 DENHAM 70,048 41,515 28,533 59.3 DD S5288 FLAUNDEN 20,011 11,809 8,202 59.0 DD S5324 GERRARDS CROSS & FULMER 224,363 132,995 91,368 59.3 DD S5351 GREAT CHESHAM 239,795 142,118 97,677 59.3 DD S5629 LATIMER 17,972 7,218 10,754 40.2 DD S5970 PENN 46,370 27,487 18,883 59.3 DD S5971 PENN STREET w HOLMER GREEN 70,729 41,919 28,810 59.3 DD S6086 SEER GREEN 75,518 42,680 32,838 56.5 DD S6391 TYLERS GREEN 41,428 24,561 16,867 59.3 DD S6694 AMERSHAM DEANERY 5,976 5,976 0 0.0 Deanery Totals 1,557,501 920,018 637,483 59.1 R:\Store\Finance\FINANCE\2021\Share 2021\Share 2021Bucks Share20/07/202112:20 Deanery Share Statement : 2021 allocation 3AY AYLESBURY 2021 Cash Recd Bal as at % Paid Share To Date 16-Jul-21 To Date A/C No Parish £ £ £ % S4675 ASHENDON 5,108 2,975 2,133 58.2 DD S4693 ASTON SANDFORD 6,305 6,305 0 100.0 S4698 AYLESBURY ST MARY 49,527 23,000 26,527 46.4 S4699 AYLESBURY QUARRENDON ST PETER 7,711 4,492 3,219 58.3 DD S4700 AYLESBURY BIERTON 23,305 13,575 9,730 58.2 DD S4701 AYLESBURY HULCOTT ALL SAINTS -

Updated Electorate Proforma 11Oct2012

Electoral data 2012 2018 Using this sheet: Number of councillors: 51 51 Fill in the cells for each polling district. Please make sure that the names of each parish, parish ward and unitary ward are Overall electorate: 178,504 190,468 correct and consistant. Check your data in the cells to the right. Average electorate per cllr: 3,500 3,735 Polling Electorate Electorate Number of Electorate Variance Electorate Description of area Parish Parish ward Unitary ward Name of unitary ward Variance 2018 district 2012 2018 cllrs per ward 2012 2012 2018 Bletchley & Fenny 3 10,385 -1% 11,373 2% Stratford Bradwell 3 9,048 -14% 8,658 -23% Campbell Park 3 10,658 2% 10,865 -3% Danesborough 1 3,684 5% 4,581 23% Denbigh 2 5,953 -15% 5,768 -23% Eaton Manor 2 5,976 -15% 6,661 -11% AA Church Green West Bletchley Church Green Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1872 2,032 Emerson Valley 3 12,269 17% 14,527 30% AB Denbigh Saints West Bletchley Saints Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1292 1,297 Furzton 2 6,511 -7% 6,378 -15% AC Denbigh Poets West Bletchley Poets Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1334 1,338 Hanslope Park 1 4,139 18% 4,992 34% AD Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 2361 2,367 Linford North 2 6,700 -4% 6,371 -15% AE Simpson Simpson & Ashland Simpson Village Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 495 497 Linford South 2 7,067 1% 7,635 2% AF Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1747 2,181 Loughton Park 3 12,577 20% 14,136 26% AG Granby Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Granby Bletchley -

Minutes of a Parish Council General Meeting Held on Monday 4Th February 2019 at 7.30 P.M

Minutes of a Parish Council General Meeting held on Monday 4th February 2019 at 7.30 p.m. in the Village Hall PRESENT: Councillors Hinds, Stacey, Keane, Markham, Ayles, and Forgham, the Clerk, Ward Cllr Geary and 1 member of the public. There was no public session: 1 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE ACTION 1.1 Cllrs Sawbridge reason illness - accepted. 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 2.1. Cllr Ayles personal interest 5.1. Cllr Stacey pecuniary interest 5.3. 3 APPROVE MINUTES OF THE LAST MEETING 3.1 The minutes of 1st October (proposed Cllr Markham seconded Cllr Hinds), 3rd December (proposed Cllr Forgham seconded Cllr Ayles) and 7th January Clerk (proposed Cllr Keane seconded Cllr Forgham) were all agreed unanimously. 4 TO RECEIVE REPORTS 4.1. Clerks Report & Review of Actions (See Appendix A1). Matters arising: 4.1.1. Item 1 – Electrician still to provide a quote for installing the clock at the Village Hall. Clerk to then contact Janie Burns at MKC to apply for a ‘public arts’ grant. Clerk 4.1.2. Item 9 – Cllr Stacey has commissioned work to prune back trees overhanging war memorial. 4.2. Report on Visit by MKC Head of Highways to Castlethorpe and Hanslope. (Cllrs Ayles and Forgham) (See Appendix A2). Matters arising: 4.2.1. Cllr Ayles has requested that the Dips at the bottom of Castlethorpe Road be inspected after the next period of heavy rainfall 4.2.2. David Frost of MKC will attend the village to look at the village entrances with a view to considering vehicle speed controls. -

An Unlikely Place to Find Village Life Graham Norwood Explores Buckinghamshire’S Maligned Marmite Town and Its Bucolic Surprises

Source: The Daily Telegraph {Property} Edition: Country: UK Date: Saturday 23, March 2019 Page: 10,11 Area: 1557 sq. cm Circulation: ABC 345618 Daily Ad data: page rate £46,000.00, scc rate £214.00 Phone: 020 7931 2000 Keyword: Stacks Property Search An unlikely place to find village life Graham Norwood explores Buckinghamshire’s maligned Marmite town and its bucolic surprises ay “Milton Keynes” to Eighth Street and (my favourite) most people and they V6 Grafton Street. think of brutalist archi- So describing it now as a grey com- tecture, roads lined with muter haven is hardly surprising, yet S Sixties-style blocks of that is only half the story of Milton flats and offices, and a Keynes. For surrounding this very town full of London’s Marmite town – some love it, others overspill residents. passionately hate it – there are several That’s hardly surprising, as it was de- indisputably lovely villages, many signed just over half a century ago as a with surprisingly good-value homes futuristic new town, when those de- given their size and the charm of their scriptions were kinder than they are local communities. today. Back then, car travel was being Look at Aspley Guise, an elegant vil- encouraged and navigation was easy lage with 13th-century roots and more thanks to its US-style grid pattern and than 20 Georgian listed buildings. It’s functional road names such as South laden with footpaths and bridleways, while Woburn Abbey and the local golf and east. Or, not far away, you find Wo- club are close by. -

Milton Keynes Councillors

LIST OF CONSULTEES A copy of the Draft Telecommunications Systems Policy document was forwarded to each of the following: MILTON KEYNES COUNCILLORS Paul Bartlett (Stony Stratford) Jan Lloyd (Eaton Manor) Brian Barton (Bradwell) Nigel Long (Woughton) Kenneth Beeley (Fenny Stratford) Graham Mabbutt (Olney) Robert Benning (Linford North) Douglas McCall (Newport Pagnell Roger Bristow (Furzton) South) Stuart Burke (Emerson Valley) Norman Miles (Wolverton) Stephen Clark (Olney) John Monk (Linford South) Martin Clarke (Bradwell) Brian Morsley (Stantonbury) George Conchie (Loughton Park) Derek Newcombe (Walton Park) Stephen Coventry (Woughton) Ian Nuttall (Walton Park) Paul Day (Wolverton) Michael O’Sullivan (Loughton Park) Reginald Edwards (Eaton Manor) Michael Pendry (Stony Stratford) John Ellis (Ouse Valley) Alan Pugh (Linford North) John Fairweather (Campbell Park) Christopher Pym (Walton Park) Brian Gibbs (Loughton Park) Hilary Saunders (Wolverton) Grant Gillingham (Fenny Stratford) Patricia Seymour (Sherington) Bruce Hardwick (Newport Pagnell Valerie Squires (Whaddon) North) Paul Stanyer (Furzton) William Harnett (Denbigh) Wedgwood Swepston (Emerson Euan Henderson (Newport Pagnell Valley) North) Cec Tallack (Campbell Park) Irene Henderson (Newport Pagnell Bert Tapp (Hanslope Park) South) Christine Tilley (Linford South) David Hopkins (Danesborough) Camilla Turnbull (Whaddon) Janet Irons (Bradwell Abbey) Paul White (Danesborough) Harry Kilkenny (Stantonbury) Isobel Wilson (Campbell Park) Michael Legg (Denbigh) Kevin Wilson (Woughton) David -

33 Bus Timetable

Effective: 01/04/2021 Monday to Friday 33 33† 33* 33A 33A 33A 33A 33 * 33† 33 Saturday 33 33A 33A 33A 33A 33 33 33 Northampton Bus Interchange ··· ··· ··· 845 1015 1145 1315 1459 1502 1740 Northampton Bus Interchange … 845 1015 1145 1315 1445 1615 1745 Delapre, London Road ··· ··· ··· 851 1021 1151 1321 1505 1508 1746 Delapre, London Road … 851 1021 1151 1321 1451 1621 1751 Wootton, Church Hill ··· ··· ··· 857 1027 1157 1327 1511 1514 1752 Wootton, Church Hill … 857 1027 1157 1327 1457 1627 1757 Quinton, Preston Deanery Road ··· ··· ··· 902 1032 1202 1332 1517 1520 1757 Quinton, Preston Deanery Road … 902 1032 1202 1332 1502 1632 1802 Roade, Churchcroft ··· ··· ··· 908 1038 1208 1338 1526 1529 1803 Roade, Churchcroft … 908 1038 1208 1338 1508 1638 1808 Roade, Elizabeth Woodville School ··· ··· ··· | | | | 1529 | | Roade, Elizabeth Woodville School … | | | | | | | Ashton, Stoke Road ··· ··· ··· 914 1044 1214 1344 1535 1535 1809 Ashton, Stoke Road … 914 1044 1214 1344 1514 1644 1814 Hartwell, Kits Close 600 720 720 923 1053 1223 1353 1554 1554 1818 Hartwell, Kits Close 726 923 1053 1223 1353 1523 1653 1823 Hanslope, The Square 609 731 731 932 1102 1232 1402 1603 1603 1827 Hanslope, The Square 737 932 1102 1232 1402 1532 1702 1832 Castlethorpe, South Street 613 736 736 937 1107 1237 1407 1608 1608 1832 Castlethorpe, South Street 742 937 1107 1237 1407 1537 1707 1837 Haversham, Beech Tree Close 618 742 742 942 1112 1242 1412 1613 1613 1837 Haversham, Beech Tree Close 748 942 1112 1242 1412 1542 1712 1842 Wolverton, Church Street 624 749 749 -

MEDIEVAL PA VINGTILES in BUCKINGHAM SHIRE LTS'l's F J

99 MEDIEVAL PAVINGTILES IN BUCKINGHAM SHIRE By CHRISTOPHER HOHLE.R ( c ncluded). LT S'l'S F J ESI NS. (Where illuslratio ns of the designs were given m the last issue of the R rt•ord.t, Lit e umnlJ er o f the page where they will LJc found is give11 in tl te margi n). LIST I. TILES FROM ELSEWHERE, NOW PRESERVED IN BUCKINGHAM SHIRE S/1 Circular tile representing Duke Morgan (fragment). Shurlock no. 10. Little Kimble church. S/2 Circular tile representing Tnstan slaying Morhaut. Shurlock no. 13. Little Kimble church. S/3 Circular tile representing Tristan attacking (a dragon). Shurlock no. 17. Little Kimble church. S/4 Circular tile representing Garmon accepting the gage. Shurlock no. 21. Little Kimble church. S/5 Circular tile representing Tristan's father receiving a message. Shurlock no. 32. Little Kimble church. S/6 Border tile with grotesques. Shurlock no. 39. Little Kimble church. S/7 Border tile with inscription: + E :SAS :GOVERNAIL. Little Kimble church (fragment also from "The Vine," Little Kimble). S/8 Wall-tiles (fragmentary) representing an archbishop, a queen, S/9 and a king trampling on their foes. S/10 Shurlock frontispiece. Little Kimble church (fragment of S/10 from "The Vine"). Nos. S/1-10 all from Ohertsey Abbey, Surrey ( ?). S/11 Border tile representing a squirrel. Wilts. Arch. Mag. vol. XXXVIII. Bucks Museum, Aylesbury, as from Bletchley. No. S/11 is presumably from Malmesbury Abbey. LIST II. "LATE WESSEX" TILES in BUCKINGHAMSHIRE p. 43 W /1 The Royal. arms in a circle. Bucks. -

Land at Castlethorpe Road Hanslope Milton Keynes

Land at Castlethorpe Road Hanslope Milton Keynes Archaeological Excavation for Triskelion Heritage on behalf of Bloor Homes CA Project: MK0054 CA Report: MK0054_1 Accession Number: AYBCM:2018.44 November 2019 Land at Castlethorpe Road Hanslope Milton Keynes Archaeological Excavation CA Project: MK0054 CA Report: MK0054_1 Accession Number: AYBCM:2018.44 Document Control Grid Revision Date Author Checked by Status Reasons for Approved revision by A 22.10.19 Anna Peter Boyer Draft Internal review Moosbauer B 3.12.19 Anna Sarah Draft QA SLC/MAW Moosbauer Cobain/Martin Watts This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology © Cotswold Archaeology Land at Castlethorpe Road, Hanslope, Milton Keynes: Archaeological Excavation CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 7 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................ 8 3. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 12 4. METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................. -

Mkpa-2018-Summer-Leaflet-3

Venues • Loughton: Behind Sports & Social Club • Bletchley (LP): Leon Park, • Medbourne: Pavilion MILTON KEYNES PLAY ASSOCIATION Queensway • MK Village: Willen Road SUMMER PLAY S ESSIONS - 2018 • Bletchley (YC): off Derwent Drive • Monkston: Community Centre Field • Bradville: Barry Avenue • Monkston Park: Village Green, Welcome to your complete guide to our play sessions running across the city this summer. • Bradwell Common: Bradwell Colindale Street Common Boulevard Play Area • Neath Hill: St Monicas Catholic Milton Keynes Play Association has been running open-access • Bradwell Village: off Loughton Primary School play sessions for many years now. We will be running at road/Primrose Road • New Bradwell (NR): Newport Road Rec numerous venues across the city and have some brand new sites for summer 2018. • Brooklands: Brooklands Farm • New Bradwell (MC): Meads Close Park Primary School/off Countess Way • Newton Leys: Anglesey View These sessions are funded by participating Parish, Town and • Broughton: Broughton Fields Primary Community Councils. We work in partnership with them • Oakgrove School: Oakgrove Secondary throughout the year to provide free play opportunities in School School several areas. We thank those that take part and provide us • Crownhill: Playing Field, next to local • Oakridge Park: Winchombe Meadows with funding. Please speak to your Parish Council about funding centre • Shenley Brook End: Church End Road us in the future if we aren’t running in your estate or local area; • Emerson Valley: Off White Horse they are in place to serve their local residents. Drive • Shenley Church End: Off Aldwycks Drive All sessions will run whatever the weather, although specific • Fairfields: in front of Barratt activities cannot be guaranteed.