Many Coloured Coats: the Systems of Academical Dress in Nova Scotian Universities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONOR T. VIBERT Professor - Business Strategy Fred C

1 CONOR T. VIBERT Professor - Business Strategy Fred C. Manning School of Business Administration Acadia University Ph: (902) 585 - 1514 Wolfville, Nova Scotia Fax: (902) 585 - 1085 Canada, B4P 2R6 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://business.acadiau.ca http://casenet.ca EDUCATION: Ph.D., University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, 1996 MBA, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, 1989 B.Comm, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, 1985 AWARDS Recipient of 2008 Associated Alumni of Acadia University Award for Community Engagement Nominated by Acadia University for a 2006 National Technology Innovation Award: The Learning Partnership Nominated for 2005 SCIP Fellows Award: Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals - Summer 2004. Recipient of the SCIP Catalyst Award for 2004: Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals – March 2004. Recipient of the Outstanding Teacher Award for 2002: Faculty of Professional Studies, Acadia University – $500.00. Recipient of the 2000 Acadia University President’s Award for Innovation: Leveraging Technology: Web Based Analysis in an Electronic Classroom Teaching Environment. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Adjunct Professor – Curtin Business School, Curtin University - 2011 - 2013 Promoted to Full Professor – Acadia University - 2007 Promoted to Tenured, Associate Professor - Acadia University - 2002 Online MBA Program Academic Coach – Faculty of Business - Athabasca University -Ongoing Assistant Professor – Tenure Track – Acadia University – 1997 – 2002 Assistant Professor – Contractual -

(In Order of Easy Walking Distance from Acadia University) Restaurants the Ivy Deck 8 Elm Avenue, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.542.186

TOWN OF WOLFVILLE DINING (In order of easy walking distance from Acadia University) Restaurants The Ivy Deck 8 Elm Avenue, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.542.1868 Open Tues., Wed. 11:30-4, Thurs., Fri., Sat., 11:30-8(ish), Sun. 12-4. Contemporary Mediterranean Cuisine. Known for their salads, pastas and sandwiches. A number of Vegetarian options. Patio. Mud Creek Grill and Lounge 12D Elm Avenue, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.697.3500 Open daily 11:30-10:00pm, Friday and Saturday until 2am. Casual pub fare plus a few extras like Kashmiri chicken and Jambalaya Penne. Library Pub and Merchant Wine Tavern 472 Main Street, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.542.4315 Open daily 11am – midnight. First-rate pub style food. A selection of premium import and domestic draft beers on tap. The Wine Tavern specializes in local wines, and cellars a fine international selection of new and old world wines. Rosie’s Restaurant and Paddy’s Brew Pub 320 Main Street, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.542.0059 Open daily. Traditional Pub style food, burgers, sandwiches, plus other entrees including a few tasty vegetarian options. A selection of great beer brewed on site. Patio. Actons 406 Main Street, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.542.7525 Open Daily. Lunch 11:30 - 2:00, Dinner 5:00 'til closing Casual, fine dining in a classic bistro style. Bistro classics like mussels and frites, or fish and chips beautifully presented. Great selection. Patio. Front Street Cafe 112 Front Street, Wolfville NS. TEL 902.542.4097 Open 9:00am-7:00pm 7 days/week Traditional cafe fare and breakfasts. -

Christopher S. Greene GIS Instructor Department of Earth Sciences Dalhousie University 1459 Oxford Street PO BOX 15000 Halifax NS B3H 4R2

Christopher S. Greene GIS Instructor Department of Earth Sciences Dalhousie University 1459 Oxford Street PO BOX 15000 Halifax NS B3H 4R2 902-880-0782 [email protected] ACADEMIC INTERESTS Geographic Information Science and Systems, Environmental Decision Making, Strategic Planning Approaches to Sustainability, Human Activities and Disturbed Landscapes. EDUCATION 2015 PhD, Environmental Applied Science and Management Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario 2009 Masters in Spatial Analysis (MSA) Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario 2005 Masters in Environmental Studies (MES) York University, Toronto, Ontario 2003 Bachelor of Science, Honours, Environmental Science (BSc. H) Wolfville, Nova Scotia 1998 Bachelor of Science, Animal Science (BSc. Agr.) Nova Scotia, Agricultural College, Bible Hill, Nova Scotia PEER REVIEWED ARTICLES (5) Greene, C. S., Robinson, P. J., & Millward, A. A. (2018). Canopy of advantage: Who benefits most from city trees?. Journal of Environmental Management, 208, 24-35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.12.015 Greene, C.S. & Millward, A.A. (2017). Getting closure: the role of urban forest canopy density in moderating surface temperatures in a large city. Urban Ecosystems, 20 (1), 141-156. doi: 10.1007/s11252-016-0586-5 Kedron, P.J., Frazier, A., Greene, C.S., & Mitchell, D. Curriculum Design in Upper-Level and Advanced GIS Classes: Are New Skills being Taught and Integrated? Accepted in GI_Forum, 1, 324-335. Greene, C.S. and Millward, A.A. (2016). The legacy of past tree planting decisions for a city confronting emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) invasion. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4, 1-27. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2016.00027 Greene, C.S., Millward, A.A., & Ceh, B. -

Mark Bovey Curriculum Vitae

Mark Bovey Curriculum Vitae Associate Professor (Printmaking), NSCAD University 5163 Duke St., Halifax NS, Canada, B3J 3J6 email: [email protected] website: www.markbovey.com OFFICE: 902 494 8209 CELL: 902 877 7697 Education 1997 B.ED. Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada A.C.E. Artist in the Community Education Program 1992 M.V.A. Printmaking, University oF Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 1989 B.F.A. Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada Solo Exhibitions 2020 Conversations Through the Matrix, (Postponed) University of Belgrade, Belgrade, Serbia 2014 World Machine, AP Gallery, Calgary Alberta 2010 Restoring the Ledge, presented by Open Studio, Toronto Ontario “Contact” 2009 Photography Exhibition 2009 The Ledge Suite, SNAP (ARC), Edmonton Alberta 2004 Between States, SNAP Gallery (ARC), Edmonton, Alberta, Canada 2003 Mind Field, invited, Alternator (ARC), Kelowna British Columbia, Canada 2001 Mind Fields, Modern Fuel Parallel Gallery, Kingston Artists Association, Kingston Ontario, Canada Invitational Small Group, Juried National or International Exhibitions 2021 Prototype Special Exhibition of Canadian Contemporary Printmaking, Pages of the Skies for the exhibition Anthem: 15 Expressions of Canadian Identity, Canadian Language Museum, Toronto Ontario Curated by Elaine Gold, (invited) 2nd Ex. Library of Alexandrina Museum, postponed until 2022, Library oF Alexandrina Museum oF Art, Alexandria Egypt Okanagan Print Triennial, Vernon Public Art Gallery, Vernon BC (jury selection) 2020 3rd International Academic Printmaking Alliance (IAPA), Online Exhibition Symposium and (invited) Canadian Curator, Selected Artists were Emma Nishimura and Libby Hague “The Art of Staying Home”. Library oF Alexandrina Museum 23 September - 6 October 2020, (juried international ex.) Washed Over – Stone Lithography as Vessel for Resilience and Metaphor, Organizer participated and juror. -

IN the NEWS Universities Are Enriching Their Communities, Provinces and the Atlantic Region with Research That Matters

ATLANTIC UNIVERSITIES: SERVING THE PUBLIC GOOD The Association of Atlantic Universities (AAU) is pleased to share recent news about how our 16 public universities support regional priorities of economic prosperity, innovation and social development. VOL. 4, ISSUE 3 03.24.2020 IN THE NEWS Universities are enriching their communities, provinces and the Atlantic region with Research That Matters. CENTRES OF DISCOVERY NSCAD brings unique perspective to World Biodiversity Forum highlighting the creative industries as crucial to determining a well-balanced and holistic approach to biodiversity protection and promotion News – NSCAD University, 25 February 2020 MSVU psychology professor studying the effects of cannabis on the brain’s ability to suppress unwanted/ unnecessary responses News – Mount Saint Vincent University, 27 February 2020 Collaboration between St. Francis Xavier University and Acadia University research groups aims to design a series of materials capable of improving the sustainability of water decontamination procedures News – The Maple League, 28 January 2020 New stroke drug with UPEI connection completes global Phase 3 clinical trial The Guardian, 05 March 2020 Potential solution to white nose syndrome in bats among projects at Saint Mary’s University research expo The Chronicle Herald, 06 March 2020 Trio of Dalhousie University researchers to study the severity of COVID-19, the role of public health policy and addressing the spread of misinformation CBC News – Nova Scotia, 09 March 2020 Memorial University researchers overwhelmingly agree with global scientific community that the impacts of climate change are wide-ranging, global in scope and unprecedented in scale The Gazette – Memorial University of Newfoundland, 12 March 2020 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT and SOCIAL WELL-BEING According to research from the University of New Brunswick N.B.’s immigrant retention rates are high during the first year and then 50% leave after 5 years CBC News – New Brunswick, 13 February 2020 Impact of gold mine contamination is N.S. -

Breathing New Life Into an Aging Academic Facility— Acadia University’S Patterson Hall Renovation

Breathing New Life Into an Aging Academic Facility— Acadia University’s Patterson Hall Renovation What do you do with a beautiful historical building that doesn‟t function well? At Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, the answer is simple—renovate...renovate...renovate! Patterson Hall—known by faculty, staff and students as “The Old Bio Building”—is a four-storey facility that was built in 1928. The complete renovation has seen it completely stripped down to its structural floors, columns and outside walls and included the removal of all materials containing asbestos. “It‟s a gorgeous building,” says Marcel Falkenham, Director of Facilities Management at Acadia University. “It now meets—and in some cases exceeds— current standards for space, light, energy consumption and air quality.” This massive renovation project began in 2008 and was completed early summer in time for the 2011 fall semester. Half of the $4.2-million cost was provided by the Government of Canada‟s Knowledge Infrastructure Program (KIP) under Canada‟s Economic Action Plan and the other half was provided by the Province of Nova Scotia. The 40,000-square foot building has new mechanical and electrical systems, new energy-efficient windows, water-conserving fixtures, upgraded insulation, high-speed wireless capability and up-to-date health and safety systems. “We will certainly be more energy efficient and realize savings from this renovation,” admits Mr. Falkenham. “The building was drafty and did not have adequate heat or air flow. Now we are confident that it meets safety codes. We replaced the sprinkler system and added an additional fire stair; it is truly a smart, healthy building.” Faculty, students and staff will be greeted with a large commons area on the main floor as they enter the facility, with classrooms and break-out rooms comprising the rest of the first and second floors. -

•Aduates Get Awards Fr. O'keefe, One Year in Office, T Encaenia

SECOND ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT EDITION IVcl. 46, No. 13 Fcfdham ColleSe. Bronx, N.Y., 10458-lune 10, 1964 Eight Pages •aduates Get Awards Fr. O'Keefe, One Year in Office, t Encaenia Ceremony To Deliver Graduation Address Last evening before a large gathering of College seniors After an estimatsd 1,550 grad- [their parents and friends, Fordham College held its annual uates don their white, purple, mark of Jesuit education." Awards Night and Encaenia ceremony. blue, yellow and scarlet silk Expansion has characterized James S. Donnelly presided as Master of Ceremonies and hoods this afternoon to receive the University dining the last .ntroduced the various speakers the first of whom was John degrees from eight schools of the few years: Lincoln Square, p. Quinn who delivered the "Lord of the Manor" address. University, Pordham celebrates Thomas More College, Dsaly Hall Tlie second speaker was James an age-old tradition when Fr. renovation and other projects, Ibgarty, President of the Vincent T. O'Keefe, president planned or underway. For the ;;ass of '64 who was selected of the Unlversity,~aelivers the Past lour years, however, Father commencement address to the has worked with the University's present the annual Encaenia Rose Hill community. wards to the ten graduates of "Self-Study" Committee insure tordham College who have ob- This myriad-colored June ex- that quality will not be sacri- tained "outstanding achieve- cercise also marks the first anni- ficed to the pressures of our col- ment" in their chosen fields. versary of Father O'Keefe's ten- lege, age population incre-is?. -

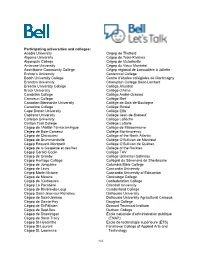

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

Whitman (Tully) House Residence: Acadia University's Only Remaining

Whitman (Tully) House Residence: Acadia University’s Only Remaining All-Female Residence By Laura Sharpe ([email protected]) On March 24, 1914, the Board of Governors of Acadia University in Wolfville announced the building of a Women’s College Residence. The plans called for the new residence to be home to 50 women, as well as housing several staff members and a matron who would oversee their wellbeing. Optimistically planned to be completed in time for the new school year in the Fall of 1914, construction fell behind. However, this did not deter 44 female students from moving into the residence during the first winter, despite its incomplete status and the ongoing construction. Shortly after its opening, the Women’s College Residence gained the nickname of Tully. Tully was reportedly the surname of an unattractive woman who lived in the area, and the male students adopted her name in their system of rating the attractiveness of female students. Under this system, “one Tully” was used to describe those deemed unattractive and “one-thousand Tullies” being the highest score possible. However, the women in the building soon adopted the name Tully as their own in solidarity against their male peers, and Tully became the commonly used name for the residence building. Owing to the decrease in male attendance caused by the war, the number of female students at Acadia was beginning to increase by 1916 and they had to be housed in two other buildings on campus. However, dividing the female students was deemed to be bad for morale, and resulted in the first slate of renovations to Tully. -

Student Profiles 2020-2021

Student Profiles MASTER OF PUBLIC POLICY 2020/2021 Canada’s Leading Policy School Master of Public Policy Class of 2020 The goal of the Master of Public Policy program is to train policy professionals who will find leadership positions across government, private and not-for-profit sectors. LIN AL-AKKAD Previous Degree(s): • B.A. in Economics Professional Experience: • Finance at Calgary Economic Development Nationality: Canadian Policy Interests: I am particularly interested in the study and harness of behavioral patterns related to market failure for more informed economic diversification and prosperity sustaining policy. Why the MPP? I am drawn to this program because of its interactive, professional, interdisciplinary nature with a diverse group of researchers from business, economics regulatory affairs, and academia. ARSHIA ALAM Previous Degree(s): • B.A. in Law and Society, University of Calgary Nationality: Canadian Policy Interests: I am interested in further exploring policy work around legal accessibility, diversity, and inclusion. Why the MPP? I chose to pursue a Master’s in Public Policy at the University of Calgary because the parameters of the program fit well with my interests in policymaking. The School of Public Policy Master of Public Policy 2020/2021—Student Profiles 1 BLAKE BABIN Previous Degree(s): • B.H.Sc. Honours Specialization in Health Science with Biology, Western University Professional Experience: • Research Assistant, Western University (Lab for Knowledge Translation and Health) • Research Assistant, Western University (Organismal Physiology Lab) Nationality: Canadian Policy Interests: I intend to leverage my background in health and biology to explore the unique niche between health security and national defense issues. -

Togas Gradui Et Facultati Competentes: the Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920

Transactions of the Burgon Society Volume 10 Article 4 1-1-2010 Togas gradui et facultati competentes: The Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920 Alan J. Ross Wolfson College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/burgonsociety Recommended Citation Ross, Alan J. (2010) "Togas gradui et facultati competentes: The Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920," Transactions of the Burgon Society: Vol. 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2475-7799.1084 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Burgon Society by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transactions of the Burgon Society, 10 (2010), pages 47–70 Togas gradui et facultati competentes: The Creation of New Doctoral Robes at Oxford, 1895–1920 by Alan J. Ross 1. Introduction During the academic year 2009/10, 18,755 students in the United Kingdom completed a doctoral degree after either full- or part-time study.1 The vast majority of these doctorates were obtained by young researchers immediately after the completion of a first degree or master’s programme, and were undertaken in many cases as an entry qualification into the academic profession. Indeed, the PhD today is the sine qua non for embarkation upon an academic career, yet within the United Kingdom the degree itself and the concept of professionalized academia are less than a hundred years old. The Doctorate of Philosophy was first awarded in Oxford in 1920, having been established by statute at that university in 1917. -

The Boom Times – Summer 2012

The Boom Times – Summer 2012 New Dean of The Faculty of Business and Economics Dr. Lloyd Axworthy, President and Vice-Chancellor, University of Winnipeg and Dr. John Corlett, Vice-President Academic and Provost are pleased to announce the appointment of Dr. Sylvie Albert to the position of Dean of the Faculty Business and Economics for a five year term, effective August 15, 2012. Dr. Albert, who is fully bilingual, joins UWinnipeg from Laurentian University where she has been Associate Dean of the Faculty of Management, and an Associate Professor of Strategy in the MBA program. She has taught since 2004 at both the undergraduate and graduate level in the areas of Strategy/Policy, Organizational Behavior, and Management. Dr. Albert's research focus has been on intelligent cities where she has played an international role as an author and lead jurist for the Intelligent Community Forum, a New York-based think tank. New Associate Chair for the Department of Business and Administration Dr. Karen Harlos, Chair of the Department of Business and Administration is pleased to announce that Professor Maggie Liu will become the Department's first Associate Chair starting August 15, 2012 for a 2-year term. In this capacity, Associate Chair Maggie Liu will assist in managing operations and programs within the Department and contributing at the strategic level. This is a substantive role that will bolster leadership capacity and stability in the Department, helping us meet operational and strategic needs. Thank you in advance for supporting and assisting Associate Chair, Maggie Liu at this import juncture in the Department's evolution.