Front Cover.Jpg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species List

Mozambique: Species List Birds Specie Seen Location Common Quail Harlequin Quail Blue Quail Helmeted Guineafowl Crested Guineafowl Fulvous Whistling-Duck White-faced Whistling-Duck White-backed Duck Egyptian Goose Spur-winged Goose Comb Duck African Pygmy-Goose Cape Teal African Black Duck Yellow-billed Duck Cape Shoveler Red-billed Duck Northern Pintail Hottentot Teal Southern Pochard Small Buttonquail Black-rumped Buttonquail Scaly-throated Honeyguide Greater Honeyguide Lesser Honeyguide Pallid Honeyguide Green-backed Honeyguide Wahlberg's Honeyguide Rufous-necked Wryneck Bennett's Woodpecker Reichenow's Woodpecker Golden-tailed Woodpecker Green-backed Woodpecker Cardinal Woodpecker Stierling's Woodpecker Bearded Woodpecker Olive Woodpecker White-eared Barbet Whyte's Barbet Green Barbet Green Tinkerbird Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird Yellow-fronted Tinkerbird Red-fronted Tinkerbird Pied Barbet Black-collared Barbet Brown-breasted Barbet Crested Barbet Red-billed Hornbill Southern Yellow-billed Hornbill Crowned Hornbill African Grey Hornbill Pale-billed Hornbill Trumpeter Hornbill Silvery-cheeked Hornbill Southern Ground-Hornbill Eurasian Hoopoe African Hoopoe Green Woodhoopoe Violet Woodhoopoe Common Scimitar-bill Narina Trogon Bar-tailed Trogon European Roller Lilac-breasted Roller Racket-tailed Roller Rufous-crowned Roller Broad-billed Roller Half-collared Kingfisher Malachite Kingfisher African Pygmy-Kingfisher Grey-headed Kingfisher Woodland Kingfisher Mangrove Kingfisher Brown-hooded Kingfisher Striped Kingfisher Giant Kingfisher Pied -

Gtr Pnw343.Pdf

Abstract Marcot, Bruce G. 1995. Owls of old forests of the world. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW- GTR-343. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 64 p. A review of literature on habitat associations of owls of the world revealed that about 83 species of owls among 18 genera are known or suspected to be closely asso- ciated with old forests. Old forest is defined as old-growth or undisturbed forests, typically with dense canopies. The 83 owl species include 70 tropical and 13 tem- perate forms. Specific habitat associations have been studied for only 12 species (7 tropical and 5 temperate), whereas about 71 species (63 tropical and 8 temperate) remain mostly unstudied. Some 26 species (31 percent of all owls known or sus- pected to be associated with old forests in the tropics) are entirely or mostly restricted to tropical islands. Threats to old-forest owls, particularly the island forms, include conversion of old upland forests, use of pesticides, loss of riparian gallery forests, and loss of trees with cavities for nests or roosts. Conservation of old-forest owls should include (1) studies and inventories of habitat associations, particularly for little-studied tropical and insular species; (2) protection of specific, existing temperate and tropical old-forest tracts; and (3) studies to determine if reforestation and vege- tation manipulation can restore or maintain habitat conditions. An appendix describes vocalizations of all species of Strix and the related genus Ciccaba. Keywords: Owls, old growth, old-growth forest, late-successional forests, spotted owl, owl calls, owl conservation, tropical forests, literature review. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

The Birds of the Dar Es Salaam Area, Tanzania

Le Gerfaut, 77 : 205–258 (1987) BIRDS OF THE DAR ES SALAAM AREA, TANZANIA W.G. Harvey and KM. Howell INTRODUCTION Although the birds of other areas in Tanzania have been studied in detail, those of the coast near Dar es Salaam have received relatively little recent attention. Ruggles-Brise (1927) published a popular account of some species from Dar es Salaam, and Fuggles-Couchman (1939,1951, 1953, 1954, 1962) included the area in a series of papers of a wider scope. More recently there have been a few other stu dies dealing with particular localities (Gardiner and Gardiner 1971), habitats (Stuart and van der Willigen 1979; Howell 1981), or with individual species or groups (Harvey 1971–1975; Howell 1973, 1977). Britton (1978, 1981) has docu mented specimens collected in the area previous to 1967 by Anderson and others. The purpose of this paper is to draw together data from published reports, unpu blished records, museum specimens and our own observations on the frequency, habitat, distribution and breeding of the birds of the Dar es Salaam area, here defi ned as the portion of the mainland within a 64-km radius of Dar es Salaam, inclu ding the small islands just offshore (Fig. 1). It includes Dar es Salaam District and portions of two others, Kisarawe and Bagamoyo. Zanzibar has been omitted because its unusual avifauna has been reviewed (Pakenham 1979). Most of the mainland areas are readily accessible from Dar es Salaam by road and the small islands may be reached by boat. The geography of the area is described in Sutton (1970). -

Observations of Owls in Western Democratic Republic of the Congo, (With a Note on African Wood Owl Vocalizations)

Observations of Owls in Western Democratic Republic of the Congo, (With a Note on African Wood Owl Vocalizations) by Bruce G. Marcot, Research Wildlife Ecologist Owls in Western Democratic Revublic of the Conno During 20 August to 15 September 2004, I engaged in an expedition to the Congo River Basin in western Democratic Republic of the Congo. I explored a number of remote forests and stayed in 8 different Bantu and Pygmy villages south of the city of Mbandaka down to Lac Ntumba (Lake Turnba) and up the Ubange md Congo Rivers and some of their tributaries, including Lambobcl River, Monioto Channel, Irebu Channel (0" 6.7' to I" 5.4' S latitude, 17" 45.0' to 18" 16.4' E longitude). The purpose of the expedition was to assist with community- based forest planning. As part of this objective, I sought owls in a variety of forest and vegetation conditions to determine which owl species may be present in more and less disturbed situations. To aid identification and to solicit responses, I carried a cassette tape with Central African owl sound^ from a cornmercia\ly- available CD set (Chappuis 2000). I also compared observations with the often-scant descriptions of owl vocaiizations gtven in Barrow and Demey (2001), Konig et al. (1999), and van Perlo (2002). In total, I encountered 11 owls among 3 species: 1 Red-chested Owlet (Glaucidium tephronotum), 8 Afncan Wood Owls (Strix woodfordii), and 2 probable Pel's Fishing Owls (Scotopelia peli). The following table summarizes my encounters:- Date Location (village) Owls Situation 8/26,28 Bogonde Drapeau Red-chested Owlet (1) secondary forest adjacent to village; --- heard only 8/27 Bogonde Drapeau Pel's Fishing Owl (1) older secondary swamp forest adjacent to jense old secondary terre fmeforest toutside villaee: heard. -

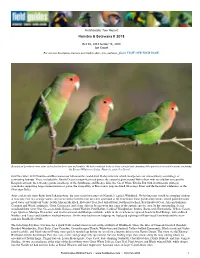

Namibia & Botswana II 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Namibia & Botswana II 2018 Oct 30, 2018 to Nov 18, 2018 Joe Grosel For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Rosy-faced Lovebirds were some of the first birds we saw in Namibia. We had wonderful looks at these colorful and charming little parrots at several locations, including the Erongo Wilderness Lodge. Photo by guide Joe Grosel. Our November 2018 Namibia and Botswana tour followed the established 18-day itinerary which incorporates an extraordinary assemblage of contrasting habitats. These included the Namib Desert's magnificent red dunes, the coastal region around Walvis Bay with its cold but very prolific Benguela current, the towering granite inselbergs of the Spitzkoppe and Erongo hills, the 'Great White' Etosha Pan with its numerous strategic waterholes supporting large concentrations of game, the tranquillity of Botswana's papyrus-lined Okavango River and the beautiful wilderness of the Okavango Delta. After a relatively short flight from Johannesburg, the tour started in earnest in Namibia's capital, Windhoek. No birding tour would be complete without at least one visit to a sewage works, and so we kicked off this tour on a first afternoon at the Gammams water purification works, which provided some good water and 'bushveld' birds. South African Shelduck, Hottentot Teal, Red-billed Duck, Southern Pochard, Red-knobbed Coot, African Gallinule, Common and Wood sandpipers, Great Cormorant, and a lone African Jacana were just some of the aquatic species seen. In the surrounding Acacia woodland there were Gray Go-away-birds, Rufous-vented Warbler, Pied Barbet, Cardinal Woodpecker, Brubru, Burnt-neck Eremomela, Yellow Canary, Cape Sparrow, Mariqua Flycatcher, and Scarlet-chested and Mariqua sunbirds, while in the reed beds we spotted Southern Red Bishop, African Reed Warbler, and Lesser and Southern masked-weavers. -

Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK

Technical Assistance Report Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK - Sapo National Park -Vision Statement By the year 2010, a fully restored biodiversity, and well-maintained, properly managed Sapo National Park, with increased public understanding and acceptance, and improved quality of life in communities surrounding the Park. A Cooperative Accomplishment of USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon- USDA Forest Service May 29, 2005 to June 17, 2005 - 1 - USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Protected Area Development Management Plan Development Technical Assistance Report Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon 17 June 2005 Goal Provide support to the FDA, CI and FFI to review and update the Sapo NP management plan, establish a management plan template, develop a program of activities for implementing the plan, and train FDA staff in developing future management plans. Summary Week 1 – Arrived in Monrovia on 29 May and met with Forestry Development Authority (FDA) staff and our two counterpart hosts, Theo Freeman and Morris Kamara, heads of the Wildlife Conservation and Protected Area Management and Protected Area Management respectively. We decided to concentrate on the immediate implementation needs for Sapo NP rather than a revision of existing management plan. The four of us, along with Tyler Christie of Conservation International (CI), worked in the CI office on the following topics: FDA Immediate -

Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

HUMAN-WILDLIFE CONFLICT AND ECOTOURISM: COMPARING PONGARA AND IVINDO NATIONAL PARKS IN GABON by SANDY STEVEN AVOMO NDONG A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Sandy Steven Avomo Ndong Title: Human-wildlife Conflict: Comparing Pongara and Ivindo National Parks in Gabon This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of International Studies by: Galen Martin Chairperson Angela Montague Member Derrick Hindery Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2017 ii © 2017 Sandy Steven Avomo Ndong iii THESIS ABSTRACT Sandy Steven Avomo Ndong Master of Arts Department of International Studies September 2017 Title: Human-wildlife Conflict: Comparing Pongara and Ivindo National Parks in Gabon Human-wildlife conflicts around protected areas are important issues affecting conservation, especially in Africa. In Gabon, this conflict revolves around crop-raiding by protected wildlife, especially elephants. Elephants’ crop-raiding threaten livelihoods and undermines conservation efforts. Gabon is currently using monetary compensation and electric fences to address this human-elephant conflict. This thesis compares the impacts of the human-elephant conflict in Pongara and Ivindo National Parks based on their idiosyncrasy. Information was gathered through systematic review of available literature and publications, observation, and semi-structured face to face interviews with local residents, park employees, and experts from the National Park Agency. -

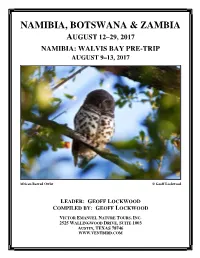

Namibia, Botswana & Zambia

NAMIBIA, BOTSWANA & ZAMBIA AUGUST 12–29, 2017 NAMIBIA: WALVIS BAY PRE-TRIP AUGUST 9–13, 2017 African Barred Owlet © Geoff Lockwood LEADER : G EOFF LOCKWOOD COMPILED BY: GEOFF LOCKWOOD VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS , I NC . 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE , S UITE 1003 AUSTIN , TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Victor Emanuel Nature Tours ITINERARY Pre-tour August 10 Flight to Walvis Bay; Kuiseb Delta and drive to our hotel in Swakopmund August 11 Swakop River mouth; coastal drive and Walvis Bay and the Walvis Bay Salt Works August 12 Swakopmund Salt Works, Rossmund Golf Course & Swakop River valley August 13 Early morning walk in Swakopmund; flight to Huab Lodge for the start of the main tour Main Tour August 13 Afternoon drive to a water point in the hills August 14 Early morning walk downstream; birding around the lodge then a drive upstream along the river; afternoon drive along the river August 15 Birding around the Huab Conservancy August 16 Early birding around the lodge, travel to Okaukeujo Camp, Etosha via Kamanjab August 17 Early birding in camp; drive to Okondeka contact spring, Newbrowni waterhole and Gemsbokvlakte August 18 Drive eastwards through the park to Mushara Lodge via Rietfontein waterhole, Halali Camp, Goas waterhole and Namutoni Camp August 19 Mushara Lodge to Namutoni; drive to various waterholes around camp August 20 Namutoni and surrounds (Klein Namutoni waterhole and Dikdik drive; Klein Okeivi and Tsumcor waterholes) August 21 Namutoni to Mokuti Lodge; flight to Bagani airstrip in the Caprivi; drive through the Mahango Game -

Namibia & Botswana I 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Namibia & Botswana I 2018 Feb 27, 2018 to Mar 18, 2018 Terry Stevenson For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This lovely Rockrunner was just one of the wonderful birds and other animals that we saw in Namibia. This endemic was found in the Erongo Mountains, where we saw 6 of these interesting birds. Photo by participants David and Judy Smith. Our March 2018 Namibia and Botswana tour followed our well tried route visiting the massive red sand dunes at Sossusvlei, the internationally acclaimed Walvis Bay Lagoon, the Erongo Mountains, Etosha National Park, and then in Botswana, the fabulous Okavango Delta, where we stayed in two of the very best lodges and traveled by private charter plane. Beginning in Windhoek we spent the afternoon at the local sewage ponds, not ideal you may think, but in a country which is largely desert any habitat for waterbirds is well worth a visit. Highlights included flocks of South African Shelduck, Hottentot Teal, and a single male Southern Pochard. Long- tailed Cormorants and African Darters perched in the trees along the edge of the ponds, and a Little Bittern flushed from a reed bed where African Gallinule was also visible; striking Red Bishops perched and displayed along the reed tops. In the surrounding acacia woodland birds were varied, with Brown Snake-Eagle, Dideric Cuckoo, White-backed Mousebird, Swallow-tailed Bee-eater, Pied Barbet, Lesser Grey Shrike, Black-fronted Bulbul and Mariqua Sunbird all making for a great start to the tour. -

Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas of South Africa

IMPORTANT BIRD AND BIODIVERSITY AREAS of South Africa INTRODUCTION 101 Recommended citation: Marnewick MD, Retief EF, Theron NT, Wright DR, Anderson TA. 2015. Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas of South Africa. Johannesburg: BirdLife South Africa. First published 1998 Second edition 2015 BirdLife South Africa’s Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas Programme acknowledges the huge contribution that the first IBA directory (1998) made to this revision of the South African IBA network. The editor and co-author Keith Barnes and the co-authors of the various chapters – David Johnson, Rick Nuttall, Warwick Tarboton, Barry Taylor, Brian Colahan and Mark Anderson – are acknowledged for their work in laying the foundation for this revision. The Animal Demography Unit is also acknowledged for championing the publication of the monumental first edition. Copyright: © 2015 BirdLife South Africa The intellectual property rights of this publication belong to BirdLife South Africa. All rights reserved. BirdLife South Africa is a registered non-profit, non-governmental organisation (NGO) that works to conserve wild birds, their habitats and wider biodiversity in South Africa, through research, monitoring, lobbying, conservation and awareness-raising actions. It was formed in 1996 when the IMPORTANT South African Ornithological Society became a country partner of BirdLife International. BirdLife South Africa is the national Partner of BirdLife BIRD AND International, a global Partnership of nature conservation organisations working in more than 100 countries worldwide. BirdLife South Africa, Private Bag X5000, Parklands, 2121, South Africa BIODIVERSITY Website: www.birdlife.org.za • E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: +27 11 789 1122 • Fax: +27 11 789 5188 AREAS Publisher: BirdLife South Africa Texts: Daniel Marnewick, Ernst Retief, Nicholas Theron, Dale Wright and Tania Anderson of South Africa Mapping: Ernst Retief and Bryony van Wyk Copy editing: Leni Martin Design: Bryony van Wyk Print management: Loveprint (Pty) Ltd Mitsui & Co. -

Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls Birding Tour

Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls birding tour 12th-29th September 2011 Burchell’s Courser – Always a good find. Tour Leader: Errol de Beer Total Bird Species: 387 (including 5 species that were only heard) Total Mammal Species: 45 TRIP DIARY: 12 Sept. 2011 I arrived at Livingstone Airport at noon after a fairly relaxed border crossing at Kazangula. I was to meet three clients each coming in on a different flight but thankfully all within an hour from each other. Sue was first to arrive, followed by Jan and Aidan, unfortunately Sue’s bag didn’t arrive so after reporting it to the missing baggage counter we wasted no time and headed straight for the magnificent Victoria Falls. We saw very little in the way of birds at the falls other than Red-winged Starling , Rock Martin and glimpses of Schalow’s Turaco as it flew by underneath us in the gorge, the falls in themselves were spectacular though, so that more than made up for it. After leaving the falls we drove by the Augur Buzzard nesting site in the Batoka Gorge and here we fortunately found one of the birds on the nest. Green Wood-hoopoe put in an appearance as did Yellow-throated Petronia. A quick stop along the Zambezi did not produce the hoped for Rock Pratincole but we did manage Little Egret, Three-banded Plover and Common Sandpiper. A nice surprise came in the form of a White-breasted Cuckooshrike, the first time I have seen one in Livingstone. The highlight of the day however was noteworthy sightings of African Hobby just outside Livingstone (thanks Chris for the heads up on where to find them), what a spectacular bird.